A Review: Visiting Unknown Ports

As part of my work, I have reviewed and adapted many HealthWrights documents. Among them I feel Reports of the Sierra Madre may be the best and most lyrical introduction to anyone wondering about the origins of HealthWrights and project Piaxtla. However, the work—without pictures—was at times somewhat opaque. I found myself asking “Who are these people?” and “What does the place look like?”

When I finally received my copy of Reports from the Sierra Madre, I was surprised at how well the illustrations and gentle editing brought the original Reports to life. I never expected to see Sixto’s facial wound, or Chon el Mudo the deaf mute, or Goyo, David’s one-armed companion, or old Apolonia the village spiritual healer. And the vistas of the Sierra Madre—which I can never visit, but only imagine—finally opened up to me: the mountain passes, the villages of Ajoya, Verano, and Jocuixtita, the school in the village of Güillapa…

We sailed away

that same night on scud of wave.

We left Eumolpo behind.

I was part of the crew.

Our anchor stone clattered

on the harbour beds of unknown ports.

For the first time, (I heard)

such names as Kelicia, Rectis…

And on an island spread

with sweet-cented grass,

a young Greek told me that in years…

—Fellini’s Satyricon (1969)

Like the Satyricon of Petronius, we have received the Reports in scattered vignettes: fragmentary, suggestive, somewhat alien and distanced by time, stimulating the imagination and inspiring in us a longing for adventure and discovery.

— Web Editor

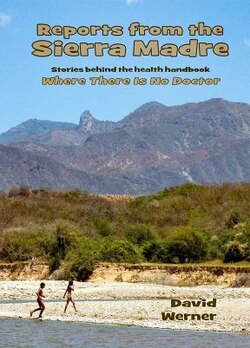

Reports From the Sierra Madre: Description

David Werner and HealthWrights (Workgroup for People’s Health and Rights) are very excited to announce the release of this new book, Reports from the Sierra Madre. This is the backstory, the real-time day-to-day journals and reports of what David experienced in the backcountry of Western Mexico, living and working side-by-side with the campesinos. Richly illustrated with hundreds of photographs as well as line drawings and sensitively painted images of birds, all by the author, this book is a must-read, both for those who have been involved in the health and disability programs that grew out of the experiences in this book, and also for those who have benefited from Where There Is No Doctor, and David’s other groundbreaking books.

From the back cover:

The Reports from the Sierra Madre comprise an on-the-spot journal of the first year David Werner spent as a novice health worker in the isolated villages of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the rugged mountain range of western México, in the state of Sinaloa. That year was 1966. He was 31 years old.

Initially, he had planned to spend one year only. However his engagement with the Sierra Madre spanned half a century, and had a far-reaching impact. Among other things, it was his work in those isolated mountains that led him to write the internationally acclaimed Where There Is No Doctor, a book that has influenced primary health care practices throughout the world.

These four reports—here published together for the first time—were initially scribbled by lamplight and sent in serial form to friends to raise funds for this unlikely grassroots endeavor. Over two hundred photos, paintings and drawings by the author have been added to the original text.

SPECIAL OFFER—Get a Signed Copy of David Werner’s New Book and Help HealthWrights!

To celebrate the release of this captivating book, David is offering you a personally signed copy of Reports from the Sierra Madre when you make a gift of $150 to HealthWrights.

This is an art book as well as a true-life saga. With over 400 pages full of color images, its price through Amazon is $55 plus postage. You can buy an unsigned copy directly online.

But we encourage you to get a special signed copy for a donation of $150 to HealthWrights, postage (in the USA) included.

Pay through PayPal by clicking here… and clicking the “donate” button …

… Or, if you prefer, send a check to:

Healthwrights

c/o Jason Weston

3897 Hendricks Road

Lakeport CA 95453 USA

If you want to know the eye-opening background of Where There Is No Doctor, this beautiful, heart-warming volume is a must.

Excerpt 1: David’s First Encounters in the Sierra Madre

adapted from the 2019 foreword

These four Reports from the Sierra Madre are now published together for the first time in book form, with many added illustrations. The reports comprise, in essence, an on-the-spot journal of the first year I spent as a novice health worker in the isolated villages of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the rugged mountain range of western México, in the state of Sinaloa.

That year was 1966. I was 31 years old. Initially, I’d planned to spend one year only. I never dreamed that my engagement with the Sierra Madre would span half a century, or have such a far-reaching impact. A biologist by training, in the early ’60s I’d been teaching for several years in a small, family-cooperative high school in the Santa Cruz Hills above Palo Alto, California. I foresaw my year in México as a kind of unpaid sabbatical, after which my plan was to go back to teach again at Pacific High School. However, one thing led to another. So here I am, 50 years later, still deeply engaged with the campesinos (villagers) in their uphill struggle for their health and rights.

Some of these battles have, at least in part, been won; others lost. But for all the ups and downs, this eventful narrative of my first year in rural México portrays the challenging experience that led to the creation of my handbook Where There Is No Doctor and the other health manuals that are now widely used throughout the majority of the world.

The idea for this venture in community-based health care in the Sierra Madre arose from a preliminary trek I took through western México in 1965, scouting for a place to take a group of my students from Pacific High – which I helped get started. Pacific, long since defunct, was an idealistic, humanitarian, and unconventional center for learning, in which I felt far more at home than in any school I’d ever been subjected to myself. I taught a course called ‘Field Ecology’, which included biology, ecology, and the impact of human activity on the natural world. To encourage what we called ‘discovery-based learning’, I would take the students on extensive field trips to areas with fascinating ecological niches and contrasting zones. There they would be encouraged to make their own observations, draw their own conclusions, and put together the pieces of the puzzle for themselves. Only after that would they turn to the books, to follow through on their findings in greater depth.

So it was, in the winter of 1965, that I hitchhiked into western México looking for an ecologically intriguing area to take a group of my students. In the state of Sinaloa, traversed as it is by the Tropic of Cancer, the desert environment to the north gradually transforms into the lusher more tropical habitat of the south. On the road map I had of the region, I randomly chose a small dirt road that extended far back into the foothills of the sierra. This I followed to the place where it ended, in a small riverside village called Ajoya. From there, I was accompanied by a friendly local schoolteacher I had met. For two days we made our way, on foot, up the steep winding mule trails high into the mountains.

As we climbed higher, we passed through the jungled ravines of the lowlands, next through the thorn-forested slopes of the lower foothills, then into the orchid-studded oak forests of the higher slopes, and finally into the pine forests of the high country. The diverse ecological zones and natural beauty of the region was stunning.

What captured me most on this expedition, however, was the friendliness and warmth of the mountain people. Although I came as a total stranger, they welcomed me into their homes and shared their food with me, even though there was barely enough to go around and many of the young children looked undernourished.

I will never forget the remarkable hospitality I received from one family. On my long hike back to the lowlands, I was so intrigued by the rich variety of plant and bird life that I’d dallied too long on the trail. The sun was already low on the horizon and it was still a long way to the next village. As I hurried past a tiny pole-walled hut on the steep mountainside, a man called out to me, “¿A donde vas, amigo?” (Where are you going, my friend?).

I replied, “A Jocuixtita” (To Jocuixtita).

“You’ll never get there before dark! There’s scorpions and snakes on the trail. Why don’t you spend the night with us?”

I gladly accepted his offer. The tiny thatched-roofed shack had a single room for the three adults and four children who lived there.

As I took off my backpack, the man sent his small son, who was limping, to look for a couple of eggs under a chicken. A half hour later, when we sat on the earth floor to eat, I noticed that I was the only one who’d been served eggs. The rest of the family ate nothing more than frijoles de olla (boiled beans), with not many beans in the broth. They had given the best food they had to a total stranger!

Soon after dark, since the only source of light was that of ocotes (pitch-pine torches), everyone bedded down. The only bedding they had consisted of a couple of deer skins and a single blanket, under which everyone curled up together as best they could. Fortunately I had a sleeping bag with me. Nonetheless – it being winter and in the mountains – that night it got so cold that even in my down bag I couldn’t keep warm. A chilled breeze drifted through the pole walls of the hut. In the wee hours of the morning it was so cold that under their single blanket the family could no longer sleep. The grown-ups got up, built a fire in the middle of the floor, and sat around it with the children in their arms, until dawn.

By daylight, I noticed that the seven-year-old boy, whom I had seen limping, had a sore on his foot, out of which pus was oozing. I asked him what had happened. He said he had stepped on a thorn … three months ago!

Then I noticed that two of the younger children, three and four years old, had large ball-like swellings on the side of their throats. I knew these were probably goiters, caused by iodine deficiency, a common problem in the mountainous regions. I also knew that goiters like this could be prevented, and in early cases cured, through the use of iodized salt.

Unfortunately I had with me neither antibiotics for the boy’s infected foot, nor iodized salt for the goiters. When I said my goodbyes, I left the family my sweater as a small token of appreciation, and then continued my trek down the mountainside. But somehow I was no longer alone. That little boy with his chronically infected foot, and his younger brother and sister with their bulging goiters, traveled with me in my head. Their ailments and their suffering seemed so unnecessary! So preventable. So treatable. What to do?

Days later, back at Pacific High School, I talked with my students about my foray in the Sierra Madre Occidental. I described the rugged beauty and striking ecological diversity. But I also spoke of the friendliness of the mountain villagers, as well as the enormity of some of their health needs. I mentioned the little boy’s foot and the children with the goiters.

As the students and I discussed the possibilities of taking a field trip to Sierra Madre, the idea emerged that in addition to studying the natural history there, we might also take some basic medical supplies to help people in the remote villages better cope with some of their unmet health needs. Presumptuous as this proposal may have seemed, everyone took it seriously. And it is what we ended up doing. But it took a lot of preparation.

As it turned out, one student had an uncle who was a doctor with experience in tropical medicine. We visited him several times, and the goodhearted doctor guided us in putting together some basic medical kits. We packaged the items in large coffee cans, which we painted white and adorned with a red cross. In terms of preparing instructions for the medicines we had to be creative. Many of the traditional healers to whom we hoped to give the kits couldn’t read or write. So we drafted the instructions using simple comic-book-like pictures, which we color coded to the different medicines and supplies.

When the time for expedition arrived, a dozen students and I drove south into western México, and then cut eastward into the Sierra Madre. Once reaching the small village of Ajoya, where the dirt road ended, we arranged with a burro driver to carry our medical kits and other luggage on his donkeys, and set out on a trek of about 100 kilometers through the mountains. We hiked from village to village, often spending the night in the home of the local curandero (traditional healer) – who invariably received us warmly. The curanderos were delighted with the medical kits, and paid sharp attention as the students carefully went over the picture-instructions with them, to be sure they understood.

When we departed, the villagers warmly encouraged us to return. I, for one, was eager to respond to their invitation. On returning to California, I decided to ask for a year off from my teaching at Pacific High School, to spend it in the Sierra Madre. One of my intentions was to study the natural history of the area and the cycle of the seasons. But my primary objective was to try to do something about the health needs there. My ambition wasn’t to play doctor, but rather to help provide information. As a biologist, I thought I might be able to share with them information from medical and health care literature, simplifying and translating it into the local language of the Sierra Madre. But my plans were open-ended. In keeping with the old saying in Spanish, I would ‘hacer el camino caminando’ (make the path by walking it).

I spent the next several months in California preparing for my sojourn in the Sierra Madre. I picked the brains of friendly doctors at Stanford Hospital. I put together a small library of texts on medicine, public health, epidemiology, nutrition and the like, and I began to collect the medicines and supplies that I might need. Many of them were donated.

To raise money for my year in the mountains I painted pictures of birds and plants. I used the technique of Sumi-e charcoal brush painting that I’d learned under the guidance of a Zen artist in Kyoto, Japan, several years before. I met this accomplished artist on a trip by bicycle that I made to the Orient. Friends helped me sell my bird paintings by organizing a festive event at the Peninsula School where I had first taught. Because I had been teaching for years in family-cooperative schools where everyone knew and cared about one another, it was easy to get a lot of participation. I gave a slide show on what I had found in the Sierra Madre, described my proposed health project there, and organized an auction of my paintings. The prices were modest. Nearly all of them sold.

Also to raise money for my year in the Sierra Madre, I sold subscriptions of my experiences there to a proposed quarterly journal. I would write the quarterly ‘Reports’ in México and send back to them to California, where some of my students’ parents agreed to type them onto stencils, mimeograph them, and send them out to subscribers. It would all be done by volunteers.

Such is the origin of the Reports from the Sierra Madre. They were drafted by lantern light, often in the wee hours, during that hectic, challenging, and often quixotic first year I spent promoting health care in the back country of the Sierra Madre.

Excerpt 2: Visiting Pipi’s Home

Dearer by the Dozen

One day near the end of July, Eustaquio, the father of Pipi, the little boy crippled by polio, came to Irineo’s house to get more corn for planting. More than 50 percent of the corn he planted at the beginning of the summer rains has failed to germinate, and the vast majority of that which has germinated has scarcely grown at all. While other mountainside plots already have waist-high corn, most of Eustaquio’s patch is only 4 or 5 inches high. He has been re-sowing where the first corn did not sprout, and praying that the rains will hold out long enough for the late-planted crop to produce. But he is discouraged.

A good yield is of critical importance to Eustaquio because less than half of the corn he plants and harvests will be his. He is working en medias for Irineo Vidaca. En medias is an arrangement whereby, when one person runs out of food and has no money, another agrees to lend him corn, lard, and beans to tide him over till the next harvest. The borrower, in turn, agrees to plant and harvest a mountainside milpa and give half the yield to the financer. This half-harvest is effectively the interest on the loan, for the accumulated debt must be paid off in corn from the borrower’s half. Thus Eustaquio, when he harvests, must turn over not only half of his harvest, but a considerable part of the remainder. If his yield is poor, he may have to turn his entire harvest over to Irineo.

“And what will you do then?” I asked him.

“Well, who knows?” Eustaquio replied with a slow smile. “Perhaps go to the coastal cities.”

All of his neighbors like Eustaquio. One can’t help liking him. There isn’t a streak of meanness in him. He has a slow, warm smile, and speaks with a kind of a drawl, yet he is a spellbinder. He would rather talk than work. When talking, he stands as if he were leaning against a wall or a tree, even if there isn’t any. When working, there is something about him that is still very relaxed. His gentle passivity has a tenderizing effect on other people. He is the sort of person who – if single – could just wander through life being nice. But Eustaquio has a family of twelve to support.

The day before yesterday, Irineo and I went up the mountainside to Los Pinos to see Esteban, who was ill. Gregorio Robles was there, and we got to talking about the sad condition of Eustaquio’s milpa, which we had passed on our way up. Goyo commented that there were entire rows where only half a dozen grains had sprouted. Esteban speculated as to whether this might be due to the prevalent güicos – small lizards that are thought to dig up and eat freshly planted grains of corn, or to the sapos – big toads that are said to dig up the kernels and plant them in other parts. It was finally agreed that the failure of Eustaquio’s corn was more probably due to the infertility of the land. Not enough years have passed since the last time it was left fallow, to allow the soil time to regenerate before replanting it.

“But why,” protested Gregorio, “didn’t Eustaquio start reseeding before now? Here it is the 3rd of August. He’ll be lucky if his plants don’t dry up on him before he gets a crop.”

“He just kept hoping that if he let it go another day it would all sprout,” scoffed Irineo. “If I hadn’t pushed him, he’d still be waiting!”

“He’s just like a little boy,” commented Esteban. “This morning, for instance, his dogs take off up the mountainside, barking like crazy, and Eustaquio takes off after them. In these days! When every grain counts that he gets in ahead of the next rain! And does he even take a gun to shoot a deer or possum if that’s what the barking’s all about? Oh, no! Just drops his planting stick and dashes after his dogs. He’s like a kid, I say.”

Everyone laughed, shaking his head, and said, “It’s true.”

While we chatted, the sky was clouding over, and Irineo and I decided we’d better get started back. Returning down the mountainside, we stopped in at Eustaquio’s hut. Pipi, who was sitting by the hut, greeted us with a huge smile. Just as we arrived, the first drops of rain began to fall. Eustaquio appeared from his field a few moments later, together with his wife and six children who had been working with him. The rain fell more heavily now, and Irineo was anxious to continue on. But Eustaquio and his family invited me to sit out the storm; I accepted their invitation. Irineo, on mule-back, went his wet way.

Eustaquio and his wife, with Pipi and the other nine children, live and sleep in a single room 18 feet long and 8 feet wide. The walls, as in many of the poorest houses, are of upright poles planted in the ground. The roof is part thatch and part baked-earth tile, with a few pieces of corrugated tin left over from some defunct mining operation. The mud stove with the cooking fire is at one end of the room. There are two collapsible burlap cots that are folded up during the day to allow some space. At night, to accommodate all twelve, every spare inch of the dirt floor is occupied, including the space under the cots. The baby’s crib hangs from the mid-beam.

There is no table, and there are no chairs, save for two crude stools made from a split log with two forked sticks stuck in holes in the bottom. At mealtime, the members of the family sit on a bed, on a log, or on the ground, putting their plates on their laps or on the log stools. As with most village families, no more than two or three persons eat at one time, not due to a shortage of conviviality, but of utensils and space. When it rains, damageable articles are shifted from one side of the room to another, depending on which way the wind is blowing.

When I learned that the family had only one blanket plus a comforter of old rags sewn together, I asked what all the children do on a cold night.

“They all get together in a ball, one on top of the other,” laughed Eustaquio. And all the young ones laughed too.

I looked at the children’s faces, one after the other. Their complexions were dark like their mother’s, yet somehow delicate, like their father’s. Their dark eyes were bright like sparrows. All the children except Pipi were extremely thin. Clearly, they were not getting enough good food. Yet I saw no sign of suffering in their faces. There was a radiance of joy in each face. Juana, their mother, showed a quiet and enduring strength. And it was apparent that their father, Eustaquio, if he could not always provide enough food, did not stint on love. They all looked hungry, but happy. And Pipi looked happiest of all, though I know there are times he must suffer.

“Won’t you eat?” asked Juana, handing Eustaquio and me each a plate of boiled beans, which we ate while the children looked on and waited their turns.

At last the rain slackened, the clouds opened, and warming sun burst through, doming the sky with a slender rainbow. Before taking my leave I asked Eustaquio once again about the crutches for Pipi, and again he assured me he would make them. But like a true carpenter, he said he would need the right kind of wood, which was jútamo, and that it would have to be cut during the dry season when the wood was drier and less apt to warp.

“Dry season!” Good God! Did he mean next spring? He has already let this year’s season pass without making them!

During the time I was in the hut, I had noticed again the strength that Pipi has developed in his arms and chest from hauling himself about with his legs dragging. I decided that rain or dry, wood or no wood, Pipi deserves crutches, and now.

Crutches for Pipi

Yesterday in Rancho del Padre, I rose at dawn, borrowed a half-broken machete, and went into the hills in search of two slender yet sturdy branches, sufficiently long and straight, shaped like wishbones but with narrower forks.

“You’re not going to find them!” was Irineo’s none too encouraging counsel as I left.

For a long while it seemed he was right. I hunted high and low. The first likely-looking branch I cut from a low, spreading gualamo tree, but the fork was too wide. Next I cut a fork from a small tree called cucharo, the bark of which strips off in shapes like spoons, but one branch of the fork was crooked. Next, palo dulce, but it proved too brittle. The palos blancos, with their heart-shaped leaves, had many suitable-looking forks, but their wood is as soft as ailanthus. Jacalosuche, the tree rhododendron, proved spongier still. I climbed high into a tepeguaje tree that arched out over a cliff and cut two promising forks – although somewhat thick – yet I found the wood was heavier than green oak. I continued my search.

At about 3pm, when it was threatening to rain, I stumbled across a patch of mahuto, a multi-stalked, fan-shaped tree of the legume family. I spotted two forks that looked perfect, but a little thin. I cut them anyway, and to my delight found the wood amazingly strong. Crutches from these forks could support my own weight! … and Pipi’s easily. Returning to the casa, Irineo led me to guinole (a kind of acacia) with many serpentine branches, from which I selected two short, curved sections to use as armpit rests.

|

|

|

This morning I went up the mountainside with the sections of branch and a chisel that – fortuitously – I had brought from California. In less than an hour I arrived at Eustaquio’s hut.

Eustaquio and the two oldest girls had left for a meeting to discuss recent cattle thefts, to be held in Jocuixtita, but eight of the children were there to meet me. Pipi, out in the corn field near the casita, was crawling along cutting weeds with a small talcuache scythe. When I arrived he hurriedly dragged himself over to greet me … a little too hurriedly, for when he got to me the top of one of his feet was cut and bleeding. But he looked up at me, smiling broadly.

The construction of the crutches was simple, and went quickly, with both Pipi and his younger brother helping. We chiseled a pair of square holes five inches apart in each of the short, curved sections of acacia; then we squared off the long, forked ends of the mahuto poles, and bending the forks closer together forced their tips into the square holes of the armpit rests. To form a hand-grip, we inserted, half-way down each crutch between the forks, a thicker, four-inch rod cut from the same mahuto. To fit snugly around the forks, we had to carve rounded grooves in the ends of these short rods of very hard mahuto, and lacking a vise, we punched holes with a planting stick in the hard-packed soil next to the hut, and inserted the rods in these holes.

Thus, with the simplest of tools, we constructed the crutches of three components each, without the help of nails, screws, wire, cord, or glue. We found the crutches held together firmly by themselves, and I tried them myself before turning them over to Pipi. They held my weight easily.

Now, came the big test. One of his brothers hoisted Pipi upright, and I placed the crutches under his arms.

Pipi struggled and did his best, but could not even manage to stand upright alone. He kept toppling over, and I kept catching him. The smile that had remained on his lips from the moment I arrived, became a strained grimace, and tears formed in his eyes. He struggled to maintain his balance … then at last, he succeeded in holding himself upright. But he was exhausted.

“Enough for now,” I said, and helped Pipi to his hands and knees again. “With practice you will learn well.”

And I am sure he will.

Before I left, Pipi tried the crutches several more times. By the last trial, he was already able to move about a little with the new crutches, falling now and then. Poco a poco, he will learn. Polio can’t be conquered in a day.

Gallery

Links

- English:

- En Español: Reportes de la Sierra Madre

- Próximamente en 2021