From Village Boy to Kind Eye Surgeon: Where Caring Goes Full Circle

Efforts to Restore a Blind Boy’s Sight

I first met Ramon and his parents through Rigoberto (Rigo) Delgado, a quadriplegic rehabilitation worker, who, in April 2013, invited me to visit a weekly “educational exchange” that he facilitates with disabled children and their families in Culiacán, the state capital of Sinaloa, México. (You can read Rigo’s remarkable story in our Newsletter #68. The day I visited Rigo he asked my advice regarding a nine-year-old boy named Ramon Ayala, who was virtually blind.

Huddled between his parents, the little boy looked unhappy and insecure. He wore very thick spectacles that made his eyes look greatly enlarged. His parents explained that their son had been born with congenital cataracts (clouding of the lenses) and also strabismus (cross eyed).

Through Seguro Social (the government health insurance program) the boy had received three surgeries. Initially the doctors had planned to insert intraocular lenses into his eyes, with hopes this would give him more or less normal sight. The opaque lenses in his eyes had been removed, but the doctors then told them that the risks were too great for further surgery. Instead, they had fitted him with the external cataract goggles he was now wearing, which left him legally blind. Yet the “risks” the doctors referred to had never been clearly specified, either to the parents or on the medical record.

Ramon could see only extremely blurred images. At school he was unable to read either the blackboard or his books, and had to feel his way to get around. The powerful “coke bottle” goggles made him dizzy and nauseous. To make things worse, he was cruelly teased by some of his classmates, who taunted him with nicknames like “Little Owl” or “the Martian.”

“What do you think might be possible for the boy?” Rigo asked me. “Social Security here in Sinaloa essentially says nothing more can be done.”

I knew that in Seguro Social, the national health insurance program, often costly procedures which are clinically indicated—even potentially lifesaving ones—are not performed, apparently for economic reasons.

Hence I replied, “I think we need a second opinion from an independent, completely trustworthy ophthalmologist.”

The first such ophthalmologist who came to my mind was Dr. Miguel Angel Alvarez, whom I have known since he was a village boy. Indeed, his education had been sponsored by the village health program that I helped set up: from secondary school through prep school, all the way through medical school. Not only was Miguel Angel a first rate ophthalmologist, he was a close friend.

The only obstacle was that Dr. Alvarez was based a long way from Culiacán, in Ciudad Obregon in the state of Sonora, where he is a professor at one of the leading training and referral hospitals in the country.

Despite his distant location, that evening I gave Miguel Angel a phone call. When I told him about Ramon, Miguel Angel chuckled and said, “Amazing you called just when you did! As chance would have it, this very weekend I will be coming to Culiacán to visit my parents, who are unwell, and I’d be delighted to examine the boy and evaluate what might be done for him. Be sure to have his complete medical history available.”

So three days later, with Rigo as intermediator, Dr. Miguel Angel Alvarez did a thorough evaluation of Ramon’s eyes, his medical record, surgeries performed, and the results.

Shortly afterwards he called me to report his conclusions. “I think the boy Ramon is an excellent candidate for intraocular transplants,” he said. “There appear to be no contraindications, and with those internal lenses his vision should be enormously improved. If his family can get him to Obregon, I’d be happy to do the procedure myself.” The out of pocket costs, he explained, wound be minimal. Because Ramon’s family has SS (Seguro Social), and since Dr. Alvarez regularly does eye surgery for the branch of SS in Obregon, he felt confident the primary costs of the procedure would be covered. The biggest cost typically not covered by SS would be the intraocular lenses. In México these are quite expensive. But Miguel Angel hoped that, one way or another, coverage for these could be arranged.

I was overjoyed by Miguel Angel’s encouraging evaluation and readiness to help. I explained to Ramon’s family that Dr. Alvarez is one of the best eye surgeons in México, and that I trusted him completely. Both Ramon and his parents had their hopes restored. The decision was made to proceed.

But there were still lots of hurdles ahead. Getting everything arranged for the surgery in Obregon took longer than any of us anticipated. As was to be expected, there were complications in the transfer of Seguro Social coverage from one state to the other, in part due to the fact that the branch in Sinaloa had decided against further surgery.

Unexpectedly, we also ran into disapproval of the surgery by the charitable foundation in Holland for whom both Rigo and I are mediators. For years, Stichting Liliana Fonds has helped fund the surgical and other rehabilitation needs of disabled children for whom we solicit assistance. So Rigo and I wrote to the foundation’s Latin American coordinator, telling her about Ramon and the prospects for his eye surgery by Dr. Alvarez. We requested the foundation’s help in paying for the cost of the intra-ocular lenses. After considerable delay, the coordinator wrote back saying she had discussed the proposed surgery with her superiors. To our disappointment, their response was that cataracts in children are rare and that surgery might be risky. So they recommended against the proposed transplants, and were unwilling to help cover the costs.

As a series of delays and obstacles arose and months passed, I began to fear that for all the good will, the sight-restoring surgery might never take place. However Miguel Angel’s commitment was unshakable. He kept reassuring us that everything would be arranged in due course. He would personally perform the surgery … and the probability of good results was high.

Had anyone else said the same with such confidence, I might have had my doubts. But Miguel Angel’s unwavering optimism kept our hopes alive. I’ve known him for 35 years, since his boyhood, and have repeatedly witnessed his tenacity in surmounting obstacles and accomplishing daunting challenges.

Let me backtrack to tell you the highlights of his story.

Miguel Angel’s Boyhood Dream

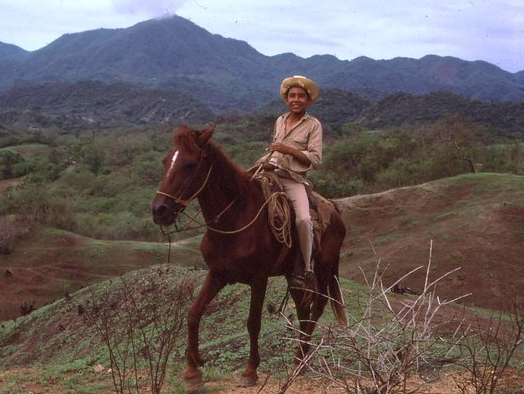

Back in the summer of 1977, a young boy walked into the Piaxtla community health post in the village of Ajoya. He stood quietly near the door, waiting to be noticed. He was a lanky youngster with dark bronze skin and Indian features. His black eyes had a bright, inquisitive, sparkle. He looked about 12.

Oddly, I didn’t recognize him, which was unusual since I knew almost all the children in village.

“Do I know you?” I asked him.

“I don’t think so,” said the boy. “But I know you. My mother brought me into the clinic a few years ago. I had big pink worms in my poop. You cured me.”

“Where do you live?” I asked.

“In El Tule. A couple of kilometers from here. Up the mountainside. Every day for the last six years I’ve hiked down to Ajoya, to go to school.”

“You must be a son of Santiago, the man with the goats.”

“Sí señor,” he said. “My name’s Miguel Angel.”

“Like the famous Greek sculptor,” I said. “What can I do for you?”

He looked me in the eyes, intensely. “Is it true that when a young person wants to go on with school real bad, but his family can’t afford it, the health program helps out?”

“No,” I said, “Not usually. But tell me about yourself.”

He said he’d just graduated from primary school – which is as far as schooling goes in the small village of Ajoya – at the top of his class. He wanted to go on to secondary school, but the closest high school was in San Ignacio, 23 kilometers away, and his family couldn’t afford it.

“Why are you so eager to continue school,” I asked.

He shrugged. “I like to know things. I want to do something with my life. Something more than herd goats.”

“If you were to go to the high school in San Ignacio, do you have any relatives there you could stay with during the week?”

“I have an aunt.”

“Would she let you live with her? Maybe if you help out with odd jobs?”

“I don’t know. I barely know her.”

“Why don’t you ask her? If she’s willing to put you up and feed you, I think we could find the bit of money it takes to pay for your enrollment, books, and other incidentals.”

“Really?!” he exclaimed. His face lit up like a sparkler. “I’ll ask her tomorrow.”

The next morning the boy left El Tule before dawn. He half walked, half jogged the 23 kilometers to San Ignacio, asked his aunt, and then hiked back to Ajoya. It was 9:00 PM when he knocked on my door.

He threw has hands skyward. “She says YES!”

Miguel’s Formative Experiences at Piaxtla

So it was that Miguel Angel began secondary school. The village health team made an agreement with him that, in exchange for assisting with his schooling costs in San Ignacio, on weekends he would come back to Ajoya and help out in the clinic. Miguel Angel filled his part of the bargain in good faith, and, in the process, learned a great deal about community health care. He mastered all sorts of skills: from vaccinating children to building latrines, from weighing babies to counseling mothers about their infants’ growth and nutrition. He learned how to stitch wounds, cast broken limbs, and identify different intestinal parasites with a microscope. From another young village apprentice, he learned how to pull teeth, drill and fill caries, and play the guitar.

Miguel Angel’s mind was a sponge. He studied my book Where There Is No Doctor from cover to cover. When people began to ask him for medical advice, he would help them look things up in the book. They appreciated his caring concern and the clear simple way he explained things. Little by little, the young man became a capable promotor de salud (health promoter).

Eye surgery. One of the most challenging experiences for Miguel Angel at the Ajoya Clinic involved assisting Dr. Rudolf Bock, an ophthalmologist from Palo Alto, California, who came to do eye surgery at the village health center in Ajoya. With so many blind persons in need of sight-restoring surgery, Dr. Bock needed all the dexterous, caring hands he could get. Miguel Angel eagerly pitched in: testing people’s vision, holding the flashlight to illuminate the surgeries, handing the doctor the right instruments when needed, and bandaging the newly operated eyes. The surgeon quickly recognized that Miguel Angel had genuine interest, a keen mind, and remarkable dexterity.

Little by little he taught the boy increasingly complex skills and gave him more sophisticated responsibilities, such as measuring the intraocular pressure of people’s eyes with a tonometer. On Dr. Bock’s third surgical visit to Ajoya, he enlisted Miguel Angel as his surgical assistant. And on his fourth visit, he taught him to perform some of the simplest surgical procedures, such as the removal of pterygium. Pterygium, called carnosidad in village Spanish, is a fleshy growth that slowly forms over the surface of the eye, as result of long-term exposure to sunlight and dust. Untreated, it can cover the pupil and cause blindness. In the mountain villages, pterygium is the most common cause of blindness, followed by cataract.

So it was that Miguel Angel, who was already a junior dentist at age 13, became a junior eye surgeon at 15. Thus he had an early start on what was to become his life’s profession.

Miguel Angel graduated from the three years of secondary school again at the top of his class. Then he worked for a year in the villager-run Clínica de Ajoya, increasing his abilities as a promotor de salud. A born teacher, he soon became one of the main facilitators in the training courses for new health promoters. Having come from a poor rural background, he had a good understanding of the underlying social, economic and political determinants of poor health. He helped his fellow villagers to analyze these root causes and take collective action to overcome them.

Village Theater for Awareness-Raising and Collective Action

One of the key methods that Miguel Angel used for awareness-raising and collective action was teatro campesino or farmworkers’ theater.

One skit he staged with a group of villagers – and acted in himself – was called “Medicines that Kill.” This skit (which is illustrated in our book Helping Health Workers Learn) shows how unscrupulous doctors and quacks prescribe expensive, unnecessary, and sometimes dangerous medicines to poor people, with the result that families spend their limited food money on inappropriate medications. As result, children may become increasingly undernourished. Their resistance to the “diseases of poverty” is lowered, and they may even die. The skit dramatically shows how overuse and misuse of medicine can be dangerous to your health.

In this “Medicines that Kill” skit Miguel Angel played the role of a health promoter who advises an elderly couple to spend their limited money on nutritious food rather than on sugar-based IV solutions which are promoted as “artificial life.”

Another underlying social cause of poor health that Miguel Angel became deeply involved in as a teenage health worker was land tenure. He and his fellow health workers helped to educate and organize landless farmers for their constitutional land rights. They also encouraged them to demand public access to water, as a human right. Many of these “struggles for health” involved confrontation with the local power structure, big landholders, and corrupt authorities.

‘Women Unite to Overcome Drunkenness.’

Miguel Angel’s “activism for a healthier community” on one occasion led to his being thrown in jail. The community protest he helped organize, and which precipitated his arrest, addressed the health problems and violence that result from the sale and heavy drinking of alcohol.

Excessive drinking in the Sierra Madre has long had a devastating impact on health, both directly and indirectly. Directly, through the personal afflictions, it causes a variety of health problems: from physical and emotional trauma to cirrhosis of the liver. Indirectly, through the malnutrition it causes in children whose fathers spend their limited food money on booze, excessive drinking contributes to health problems in children.

Because of the high frequency of violence and deaths resulting from collective drinking, the cantina (public bar) in Ajoya had been shut down by the municipal government more than a decade before. It remained closed until the early 1970’s, when the son of the president municipal talked his father into reopening the cantina.

While the reopening of the cantina was celebrated by many of the men, many women were upset. They knew the dangers it would bring, not only of physical and domestic violence, but also of food shortage and hunger.

It was here that Miguel Angel played a key role in mobilizing the women to take a stand. He worked with a group of women and children to put on a village theater skit that they titled, “Women unite to overcome drunkenness.” Not only did the skit dramatize the drastic and sometimes deadly problems resulting from inebriation, it also explored united action that the village women could take to protest and hopefully close down the bar.

As a result of this collective action—which the municipal president and his son called rabble rousing—the president sent a squad of police to Ajoya to arrest Miguel Angel and a collaborating school teacher. They were hauled to San Ignacio and thrown in jail.

This triggered the women in Ajoya to take more assertive action. They trooped by truckloads to San Ignacio and marched outside the jail, demanding release of their “political prisoners.” They waved placards saying, “WE DON’T WANT A CANTINA, WE WANT SOURCES OF WORK.”

The demonstration continued until the prisoners were released. But Miguel Angel refused to leave his cell until he was given a written statement, either naming what crime he had been arrested for, or stating he had been arrested without charge. With the women still clamoring outside, the authorities finally gave him a note stating the latter (released without charge). With this note, Miguel Angel and a group of women traveled to Culiacán, the state capital, and requested an audience with the Governor. The outcome was that the Governor reprimanded the municipal president for abuse of power, and ordered that the cantina be shut down.

The story of the women’s action in Ajoya was picked up by the state newspapers. As a result, women in several other towns up and down the state took similar action to shut down the bars and illegal “drinking holes” in their neighborhoods.

Back to School Again

While Miguel enjoyed his role as a village health promoter, and made a big contribution in many ways, his heart was set on continuing his studies—with the dream of someday becoming a doctor, and, if possible, an eye surgeon.

After spending a year with the Piaxtla health program in Ajoya, following his completion of secondary school, arrangements were made for Miguel Angel to study in a Preparatoria (college prep school). This he did in México City, where an artist friend of ours, Emile Nava, generously gave him free room and board. Again, Miguel Angel graduated at the top of his class.

On finishing la Prepa, Miguel Angel spent another year helping at the Piaxtla Health Program, and then applied to the Sinaloa state medical school in Culiacán. However, many of his fellow villagers were skeptical. Although they appreciated the young man’s abilities and determination, they couldn’t imagine him ever becoming a doctor. To them it seemed utterly impossible that one of them, a lowly campesino, could do so. Only high class folks from the cities had the smarts to become real, titled médicos.

But Miguel Angel fooled them all. Not only did he complete the five years of med school at the top of his class, but his fellow students elected him to give the graduation address.

When the day of the grand ceremony arrived, all the graduating med students showed up dressed in tuxedos and elegant dress. But not Miguel Angel. When he walked on stage to give the graduation address, everyone gasped. The lanky, dark youth was dressed, not like a graduating doctor, but as a campesino (farmer). He wore pantalones de mezclilla (jeans), huaraches (sandals with car-tire soles, a straw sombrero, and a shirt tied in a knot at the front. He paused before starting to speak. Finally the murmurs quieted down and the perturbed audience just stared. How dare he?

Miguel Angel didn’t read from his script as he’d planned. Rather he delivered it by heart, in every sense. He challenged his fellow students—and his professors—to work for the people, not the money. He criticized the vast inequalities in México, both in wealth and health. He decried the fact that most doctors work in the affluent urban neighborhoods, rather than in the poor neighborhoods and rural areas where the needs are greatest. He decried the superior attitude of doctors who think they deserve higher earnings and greater respect than the farm-workers who grow their food. “Most people can live fairly well without medicines,” he pointed out. “But no one can live without food!”

He stressed how important it is that doctors–for their own good as well as that of others-relate to those they serve as equals and as friends: as persons rather than as “patients.”

Graduate Training in Ophthalmology—and Specialization in Corneal Surgery

After completing medical school, graduating doctors are required to spend a year of public service, typically working in a government health center in an under-served neighborhood or village. Miguel Angel requested and was granted to do his national service in Ajoya, where he worked closely with the Piaxtla team of village health workers.

After Miguel Angel finished his year of rural service near Ajoya, he continued to work with the village health program in Ajoya for nearly two years. He was joined by his new wife, Ana Luisa, who had been a fellow student in medical school.

But the young doctor´s big dream was to specialize in ophthalmology and become an eye surgeon. With his outstanding performance in medical school and excellent recommendations from his professors, he was accepted into the Ophthalmology Department of the Medical School in Guadalajara.

As always, Miguel finished his residency in ophthalmology with flying colors, as the most accomplished trainee in his group. He began to make plans to further specialize in corneal surgery in México City.

But to his great disappointment he was not admitted. The rejection had nothing to do with his grades or ability, which were outstanding. Rather, he was apparently turned down because of humble origin, his dark skin, and lack of a prestigious pedigree. In México City, the top ophthalmologists belonged to an elite club of upper class high-brows with notably Spanish ancestry. They were not about to accept into their ranks such a lowlife as an indio campesino, regardless of his academic qualifications. Miguel Angel, together with his professors from Guadalajara, pounded on the regal doors in vain.

It was then that an ophthalmologist from Palo Alto, California, Dr. Lee Shehinian, came to the rescue. Dr. Shehinian, like Dr. Bock before him, had made several trips to Ajoya to perform free surgery on villagers with eye problems. He had been highly impressed by both the skills and attitude of the adolescent health worker, who had already learned to do simple eye surgery (pterygium removal) under the guidance of Dr. Bock. Lee, in turn, took Miguel Angel under his wing and taught him additional skills. The two became close friends. Indeed it was Lee, himself a specialist in corneal transplants and laser optical corrections, who put the bug in Miguel Angel’s ear to specialize in that field.

When Miguel Angel was turned down from corneal-surgery residency in México City, Dr. Shehinian talked with a colleague in Tucson, Arizona, who was a world renowned corneal surgeon. At first his colleague had misgivings, but as he began to work with Miguel Angel, he soon realized that the youth was exceptional, and took him on as his personal protégé. He taught Miguel Angel the latest procedures for cataract surgery, corneal transplant, and many other state-of-the-art operations. But the legal logistics were a challenge. Because Miguel Angel wasn’t licensed to practice medicine in the United States, his hands-on surgical practice took place in a small eye clinic in Nogales, México, on the Mexican side of the border, only an hour south of Tucson.

In time, Miguel became a practicing full time eye surgeon in the Nogales clinic. After finishing his specialty training, he opened his own small eye clinic in Nogales, where he worked for more than two decades. He also devoted time to training other Mexican ophthalmologists in the advanced surgical methods of cataract and corneal surgery that he’d learned in Tucson. Both his surgical and teaching skills were much acclaimed, and in 2011 he became a tenured professor of ophthalmology and specialized surgeon at the renowned referral hospital in Ciudad Obregon.

Despite his high level of skills and recognition, Miguel has retained his commitment to serving the poor. From the time he became an eye surgeon, he began making periodic trips to Ajoya and other villages to examine persons with eye problems. For those who needed surgery, he was often able to do it virtually free of cost at a surgical center in Culiacán.

One of the first persons from Ajoya on whom Miguel Angel operated was blind Ramona, an elderly woman who had been sightless for years due to cataracts. She had wandered from house to house begging for food and a place to stay. Eventually, PROJIMO, the village rehabilitation program that grew out of the Piaxtla health initiative, took her in.

Miguel Angel removed Ramona’s cataracts and inserted intraocular lenses. For the old woman, her restored vision was like a gift from the gods. Returning to PROJIMO, she was so happy to be able to do something helpful, she would spend all day sweeping. She swept the kitchen, the dormitories, the workshops, and the grounds. As soon as everything was swept, she would start over again. Her constant sweeping dug holes in footpaths. They had to be filled in later and some workers complained. But there was no stopping her.

Miguel Angel also did a big favor for Jason Weston, then co-director of our small non-profit organization, HealthWrights. HealthWrights operates on a shoestring and most of our help is volunteer. At a surprisingly young age (early 40s), Jason was diagnosed with a cataract in one eye, and there was no way he could afford the high cost of surgical correction in the US. He had no health insurance. So I contacted Miguel Angel in Nogales, who said, “Send him down!” A few weeks later he removed Jason’s cataract and put in an intra-ocular lens, at a fraction of the cost in the US. The results were excellent.

Ramon Ayala’s Eye Surgery

Several weeks went by after the first steps were taken to clear the way for Dr. Miguel Angel Alvarez to operate on Ramon Ayala. Working out the logistics to transfer the Seguro Social health insurance from one state to another proved to be a complex and difficult undertaking. And the lack of support from the Foundation we worked with in the Netherlands created additional economic barriers. But through all these obstacles, Miguel Angel remained calmly confident it would all work out.

And sure enough, after a couple of months, the pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place. Not only did Miguel Angel convince the headquarters of the Seguro Social in Obregon to agree to cover the costs of the procedures, he convinced them to cover the cost of the intraocular lenses, something they rarely do. And surprisingly, after further correspondence with Stichting Liliane Fonds, the Dutch foundation agreed to help with the transportation costs to and from Ciudad Obregon.

In the end, everything worked out amazingly well. Ramon and his parents were transported to Obregon, a final medical workup was done, and in January 2014 Miguel Angel performed the most modern, minimally invasive procedure to insert an intraocular lens into Ramon’s dominant eye.

A couple of days later, Miguel Angel sent me an email with the results of the surgery. He said, “What a marvelous experience it was, both for me and for Ramon, when I removed the bandage the day after the operation. The kid was literally dancing! He cried out with delight, ‘I can see! I can see EVERYTHING!’ For me this is the reward I most treasure, for all the long years I put into study and training. It is my greatest joy!”

One month later, in February, Miguel Angel operated on Ramon’s other eye. The results were equally successful. Ramon and his parents returned to their home in Culiacán, overjoyed.

The most important surgery was complete and Ramon now had good vision. The only procedure remaining to be done was for the strabismus, to align his two eyes in the same direction. Compared to the cataract surgery, this is a relatively simple intervention, and Miguel’s initial recommendation was that an eye surgeon in Culiacán perform the operation.

However, things had gone so well so far that I didn’t want to take any chances. In México there are excellent, highly competent surgeons. But there are others who are so incompetent they shouldn’t be allowed to practice. I therefore told Miguel Angel I’d feel happier if he’d do Ramon’s strabismus surgery himself. And he agreed.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |