Once again, the health workers of Ajoya, Mexico, have shown their pioneering spirit and creativity. Their new rural rehabilitation project, which we mentioned briefly in our last newsletter (#14, Jan. 1982) has evolved into an exciting and comprehensive program. It is the main topic of this newsletter. But first we would like to bring you up to date on some of the other news and events that have taken place in Ajoya over the last 19 months.

What’s Going On In Ajoya?—In the Shadow of The Government Health Center

Big changes have taken place in the community-based health programs in Ajoya—in the ‘home’ village of Project Piaxtla. Nearly 3 years ago the Mexican government put a health center in Ajoya with a doctor who provides free services and lots of free medicine. Meanwhile, the focus of Project Piaxtla is turning from ‘medical care’ toward more fundamental factors affecting health—namely social and political issues. The village team has put much emphasis on organizing groups of campesinos to define their constitutional rights in questions of land tenure, grazing rights, public water supply, etc. The local people have begun to discover that there are alternatives to silently suffering the abuses and corruption of those who hold the land and power. They have learned that in unity they have strength. They have succeeded in recovering communal land for the poor, removing a corrupt administrator (of the public water system) from office, taking the government subsidized store out of the hands of a profiteering rich family and putting an honest peasant in charge, and organizing campesinos in several villages to start cooperative corn banks in order to escape the exploitative loan system of the rich.

In the process, health workers and village leaders have been jailed, and several attempts have been made to close down the village clinic. But newspapers, friendly doctors, and university groups have stood up for it, and Piaxtla struggles on.

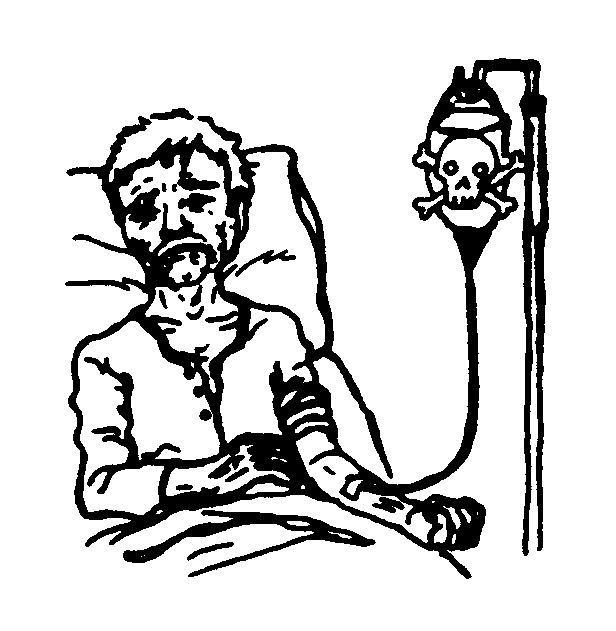

The new government health center has had a demoralizing effect on the village health team. For years, the health workers have worked with the community to help people toward sensible self-care. They have tried to demystify medicine and have discouraged the overuse and misuse of medicines, especially injections, vitamin tonics, cough syrups, diarrheal ‘plugs’, unnecessary antibiotics, and unnecessary IV’s (intravenous solutions). It took years, but people were learning to use medicines more sensibly. In 15 years, child mortality dropped to one quarter what it had been when the program began. Spending less on medicines and more on food was, of course, only one factor in lowering child mortality—but an important factor.

Now, with the new government health center, people forgot almost overnight the sensible approach to medicine that they had learned over the years. Today people flock to the government health center to stock up on cogh syrups, diarrheal ‘plugs’, antibiotics and vitamins. Old and anemic persons are once again routinely given IV solution (known as ‘artificial life’) as a pick up. It is all supposed to be free—but many of the doctors who rotate through the center find ways of taking a great deal of money from the people (by referring patients to private ‘surgical centers’ in the city for costly surgery they often do not need). One of the government doctors stole hundreds of thousands of pesos from gullible farm families and caused the death of a child through wrongly administering a dangerous medicine. The village team tried to expose this doctor by putting on village theater potraying his deeds. As a result, this doctor threatened to kill the village health workers if they continued to expose him. He lied about the village clinit to government authorities, who once again tried to close it down. Only when the doctor made both his young village auxiliary nurses pregnant did the government fire him.

Through this and countless other experiences, the village health team has learned a most important lesson: Only when the whole corrupt system is changed so that health personnel at all levels hold the people’s interest at heart, can health education really be lasting and effective.

Sharing Experiences, Learning New Skills

The Ajoya health workers are trying hard to share their experiences with others. They have conducted 3 ‘educational exchanges’ in Ajoya which village workers from other programs in Mexico and Latin America have attended. In the spring and summer of 1982, they led workshops on teaching methods for health educators and health workers in Nicaragua and participated in the first international Child-To-Child seminar in Guatamala. Refresher courses have been held in nearby mountain villages.

Although the Piaxtla team has trained health promoters for the Ministry of Agrarian Reform and rural “cultural promoters” in the case of Where There Is No Doctor (WTND) the Ministry of Health has, until recently, done more to obstruct than to assist the village-run program.

This September, however, IMSS/COPLAMAR, the Mexican government agency that set up the new health center in the first place, has invited Piaxtla team members and David Werner to participate as instructors in an upcoming international course. The same agency is also estabilshing a new promotores system for all of Mexico. They will use WTND as their text, and they have asked Piaxtla members to advise them. As for the government center in Ajoya, 2 of Piaxtla’s senior health workers now in medical school expect to be assigned here when they graduate as doctors.

Decentralizing the Piaxtla Corn Bank

In the same spirit of widening their area of action, the Project decided to decentralize the corn bank that has been effective in reducing malnutrition and getting poor families out of debt. So many families wanted to participate that the corn bank could not be managed out of Ajoya alone. Now there are 5 new independent corn banks in outlying villages. Following a visit this September by Roland Bunch, World Neighbors’ Mexico and Central America Coordinator, the health team decided to invite a Guatemalan campesino to Ajoya. This campasino will introduce local slash-and-burn farmers to a simple low-cost contour ditch system suitable for the marginal hillsides that the poor are forced to cultivate. The villagers expect that the system will triple corn yields, improve their plots, and protect the dwindling forests and eroded lands of the area. The Piaxtla team will be paying part of the Guatemalan’s expenses with their monthly income from WTND. Roland Bunch’s book on community-based agricultural improvement, Two Ears of Corn, is not being distributed by the Hesperian Foundation.

Project PROJIMO—A Villager-Run Rehabilitation Program for Disabled Children in Western Mexico

The most exciting recent development in Ajoya is Project PROJIMO, the new rehabilitation program for disabled children and their familities.

The following 10 pages are highlights from a new 60-page booklet on Project PROJIMO now available from the Hesperian Foundation (see brochure [missing]).

The Need

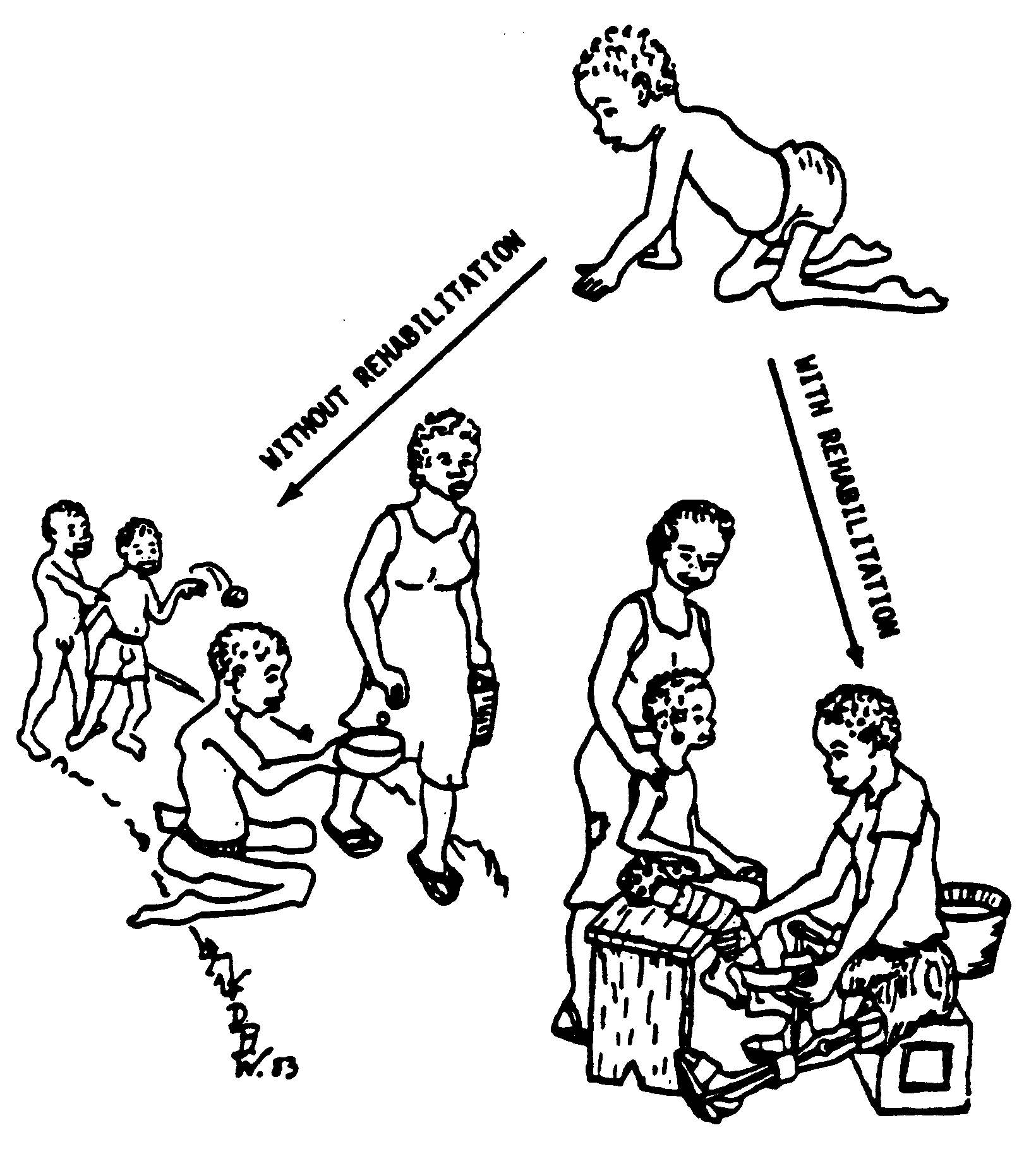

The need for an appropriate technology of rural rehabilitation is enormous. Severe physical disability affects the lives of millions of children and their families mostly living in rural areas of developing countries. Polio, cerebral palsy, and deformities caused by accidents, burns and infections are among the most common causes. But the majority of disabled children never receive the therapy, family guidance and orthopedic aid they need to develop their potential capabilities. The infrequent rehabilitation services that exist are mostly provided by expensive professionals in the cities—and even there they are available only to a fortune few. There is a great need to simplify and extend the science of rehabilitation, physical therapy, and orthopedic aids so that basic skills are widely available to community health workers and through them to the familities of disabled children.

What is PROJIMO?

Project PROJIMO in western Mexico is a modest yet innovative response to this enormous need. It is a rural rehabilitation program run by local villagers, most of them disabled. The main purpose of the program is to give families the understanding and skills they need to help their disabled children develop their full potential. The project is structured to develop self-reliance in all who participate: workers, parents, and children. It is a community-based program in so far as it is directed by local persons from poor farmworking families, and has the participation, in various ways, of much of the community.

What Does PROJIMO Mean?

PROJIMO is a Spanish word for “neighbor” in the most kindly sense as in “love your neighbor”. But P.R.O.J.I.M.O. is also an acronym standing for “Programa de RehabilitatiO/n Organizado por Jovenes Incapacitados de ME/xico Occidental” or “Rehabilitation Program Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico”.

How Did PROJIMO Get Started?

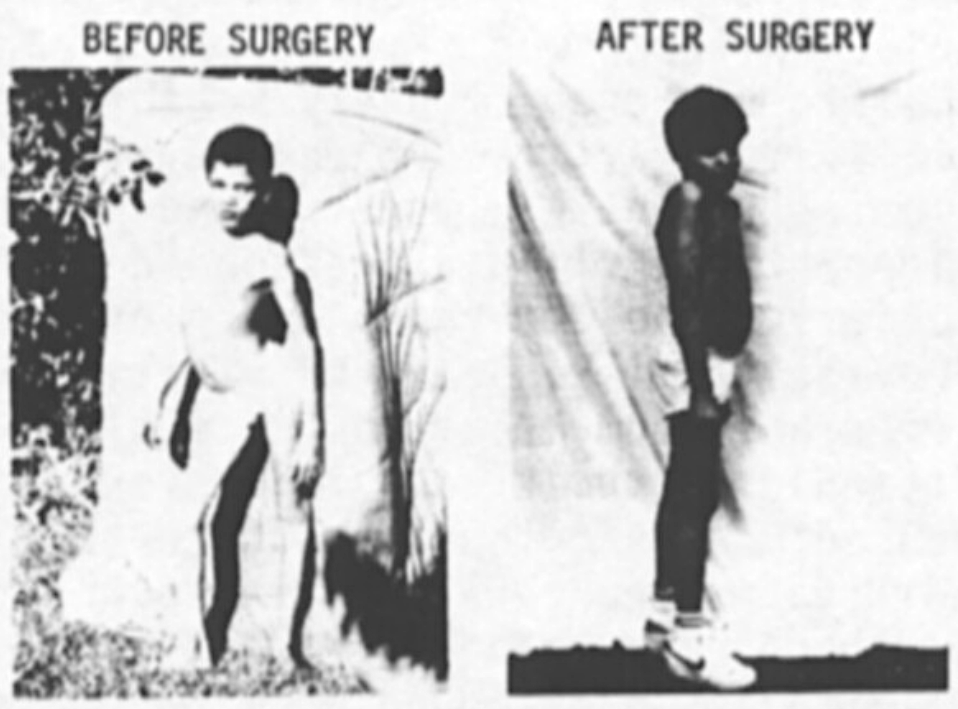

Even from its early years, Piaxtla had a unique involvement with disabled children. Children with polio and other disabilities needing orthopedic surgery were occasionally brought into the Ajoya Center. Surgery proved too expensive in Mexico. So in 1970, arrangements were made for selected children to receive free surgery and braces at Shriners Hospital in San Francisco, California.

When children who had been dragging themselves around on their hands and knees returned home walking with crutches, the word spread rapidly. Soon disabled children from far and wide were arriving at Ajoya, and the health team did its best to make arrangements at Shriners for those in greatest need of surgery.

A problem arose with the repair of braces (calipers). Village children are very active. Frequently their braces break. Or they outgrow them. The health workers could not depend on outsiders for repairs.

In 1975 Piaxtla sent a village health worker, Roberto Fajardo, to study brace repair at Shriners. Roberto was the first of the village health workers to receive special training in Rehabilitation.

As the years went by children with different disabilities continued to arrive at the health center. Some were taken to Shriners Hospital. But many had problems that did not require hospitalization or surgery. Some needed wheelchairs and others needed artificial limbs, still others needed simple therapeutic exercises. The children’s familites needed advice on how to help their children become as independent as possible, despite their handicaps. But the village team lacked the knowledge and skills to do very much.

Finally the village health workers came together to discuss what they could do better to meet the needs of the many disabled children who came to them. They decided to start a community rehabilitation program—if the villagers were willing. They called a village meeting and presented the idea. The community responded enthusiastically. Several women offered to provide room and board to visiting children and their families. Local craftsmen offered to help in converting an unused mud brick building into the rehabilitation center. And the school children offered to help build a rehabilitation playground.

What Does PROJIMO Do?

The main job of Projimo is to HELP FAMILIES OF DISABLED CHILDREN TO BECOME AS ABLE AND INDEPENDENT AS POSSIBLE IN HELPING THEIR CHILDREN IN WAYS THAT ARE INEXPENSIVE AND ENJOYABLE.

This means it does it’s best to:

- TEACH FAMILIES to carry out simple therapy and exercises, build aids and equipment, and encourage self-reliance in their children;

- CREATE COMMUNITY SUPPORT by bringing together families of disabled children, providing examples of disabled persons as happy and productive members of society, encouraging disabled and non-disabled people to study, work, and play together, coordinating the work of village volunteers, and educating the community through role plays and Child-To-Child activities;

- PROVIDE REHABILITATION EQUIPMENT, (braces, prostheses, walkers, wheelchairs, etc.) ORTHOPEDIC PROCEDURES, (such as correcting club feet by casting) and PHYSICAL THERAPY;

- ARRANGE FOR FREE SURGICAL CARE at hospitals in the USA for severely disabled young people who cannot be helped locally.

Who Makes Up the PROJIMO Team?

PROJIMO was started by disabled health workers from Project Piaxtla, with Roberto as coordinator. They invited disabled local villagers to join the team. In addition, they recruited 2 able-bodied craftsmen (one a blacksmith and leather worker, the other a welder and mechanic) to teach their skills to disabled workers. David Werner, North American pioneer in village health care (also disabled) became program adviser. The PROJIMO work team has gradually grown to 15 (10 disabled).

Javier Valverde, who had surgery for foot deformities at Shriners Hospital, also studied brace-making at a San Francisco brace shop, and is now one of the leaders of PROJIMO. The team elected him ‘oustanding worker of the year.’

Marcelo Acevedo was disabled by polio. Project Piaxtla helped Marcelo get surgery, schooling, and trained him as a village health promoter. Later, Marcelo joined the PROJIMO team. He studied brace-making as an apprentice in orthopedic shops in Mexico City and in the U.S.

Don Ramon, left, a local sandalmaker, disabled by an old bullet wound and arthritis, is the oldest member of the team.

Teenaged Ruben (on left), disabled by polio, first came for treatment and alter joined the staff. Here he helps with the record keeping. Ruben had never worked before. When he received his first play, it was the happiest day in his life.

Conchita, with cerebral palsy, first came for help learning to walk. Later she joined the team, especially to become the friend and helper to Teresa, a girl with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Other disabled North Americans have visited PROJIMO to share skills and ideas. Ralf Hotchkiss, master wheelchair designer, and Bruce Curtis, organizer andcounselor, have advised the team. Rehabilitation professionals from Mexico and the U.S.A. have also come to learn and to teach.

Many villagers have helped (for example, by building sidewalks and wheelchair ramps and opening their homes to disabled children and their familities). They too are part of the PROJIMO team.

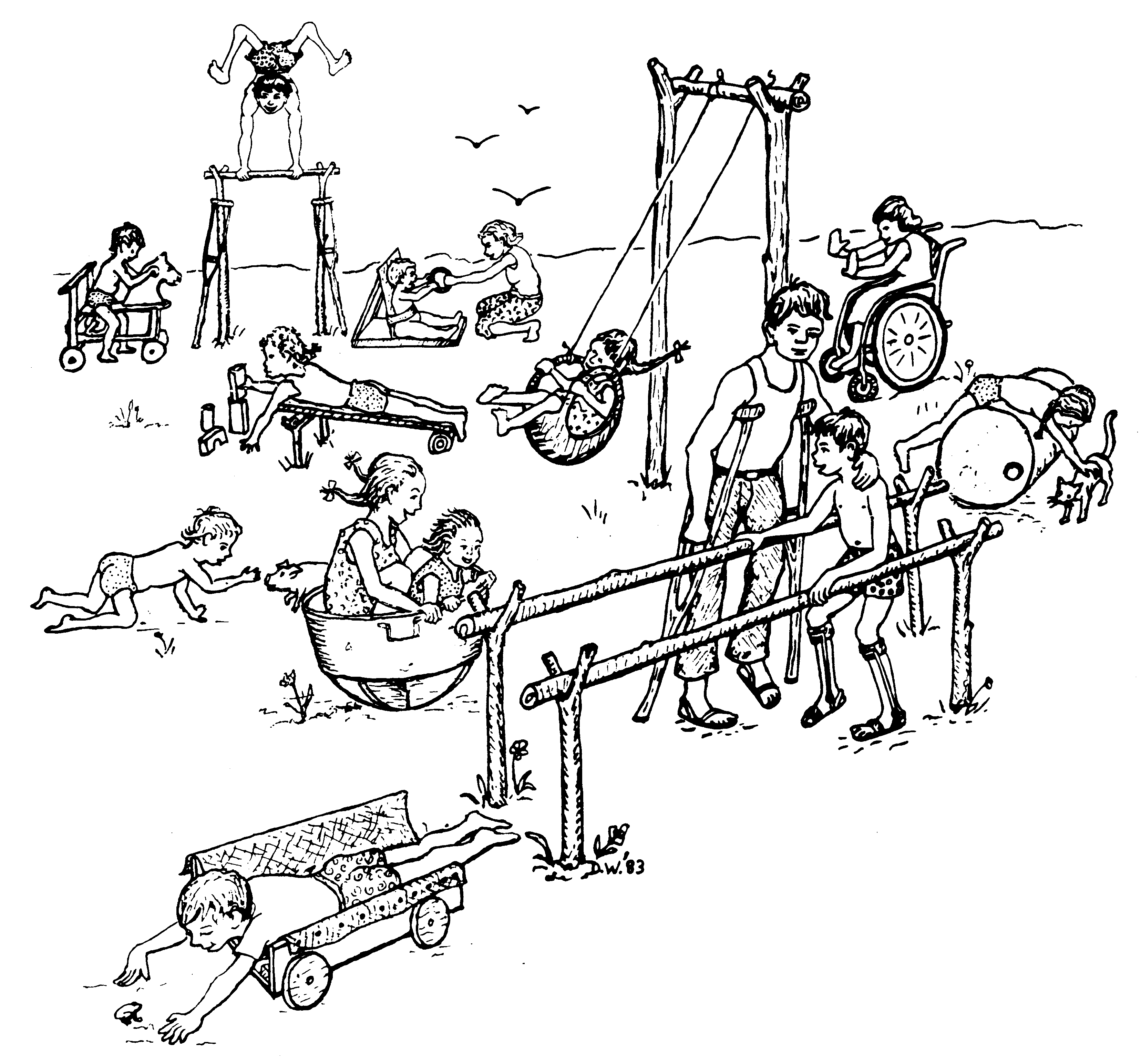

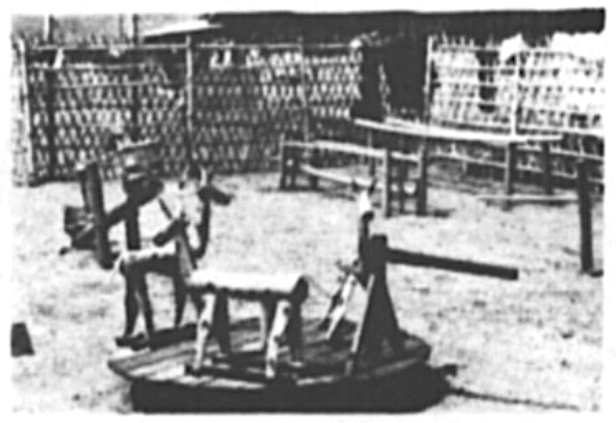

The Rehabilitation Playground

Setting up a playground was one of the first and most visible activities of the new program. The team decided to model it after a bamboo rehabilitation playground in the Khao-i-dang refugee camp in Thailand. (David Werner had taken photos on a recent visit and shown them to the villagers.)

However, there was to be one big difference. Local able-bodied children halped to make the playground, with the understanding that they, too, be allowed to use it. The team felt it was important that disabled and able-bodied children play together.

The children worked enthusiastically on the playground, which is no referred to affectionately by the villagers as ‘el Parquecito’—or The Little Park.

|

|

|

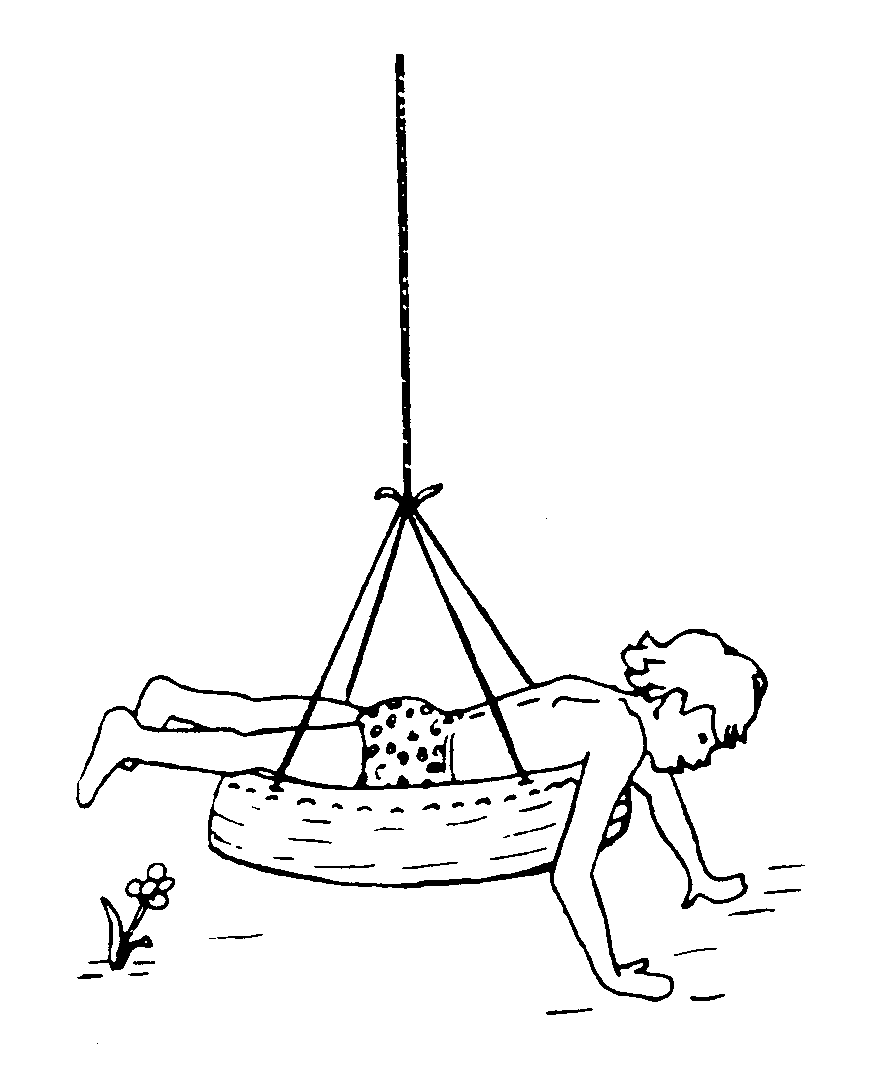

One of the main ideas of the playground is to give parents of disabled children ideas for exercise aids and playthings they can make at home using local resources at almost no cost. Parents can try out different types of equipment with their child—those that the child likes they can make themselves.

For example, the playground has a variety of swings suitable for almost any child.

|

|

|

Technology

Several workers have become remarkably skillful—even creative—at making braces, special seating, walkers, and therapeutic aids. They have also learned to straighten contractures and correct club feet. They have consistently had good results.

Wheelchairs

Many disabled persons need wheelchairs and cannot afford them. Those that do have them often have chairs that are inadequate for their needs or are so broken down they barely move. For villagers—or poor people from the cities who live on unpaved streets—no appropriate wheelchairs are available commercially.

For this reason, PROJIMO began to create rugged ‘rough terrain’ wheelchairs.

Braces (Calipers)

PROJIMO has been experimenting with ways to make low-cost, lightweight braces.

One experiment has been to use old plastic buckets. The plastic is headed in an oven over a plaster mold of the child’s leg.

Artificial Limbs (Prostheses)

The challenge in producing artificial limbs is to make them at a cost poor people can afford. Within a month after PROJIMO began to make prosthetic legs, a request came from an orthopedic surgeon in the state capital asking if he could refer amputees to the village rehabilitation center. Although high-quality modern prosthetics are available in the city, most of the amputees cannot afford them.

Salvador, one of the village health workers, learned how to make artificial legs at the Khao-i-dang refugee camp in Thailand.

Relearning to Smile—The Story of Teresa’s Rehabilitation

To close this statement on Project PROJIMO, it seems fitting to tell Teresa’s story. It is not really a success story—not yet. For Teresa’s rehabilitation has been a slow struggle; she still has a very long way to go. We tell her story because Teresa is the child who has spent the most time with PROJIMO (7 out of the first 12 months). She is the child who has most tested, frustrated, and enlarged the team’s capacity for personalized aids, creative adaptations, therapy and love.

Theresa has suffered from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis since age 7. When her mother first brought her from a distant village at age 14 her body had long since stiffened into the shape of a chair. The only thing that she moved as her eyes. Her joint pain was so great that she pent every night crying. Years before, a doctor had prescribed aspirin, but in time she developed such stomach distress that she had stopped taking it.

Theresa had lost hoped. Once she had been a cheerful, ordinary child. She had completed 3 years of school. Now she spent her life sitting silently in front of a television. She spoke very little, answering questions with single words. It was seeks before the PROJIMO team saw her smile.

The PROJIMO team as once put her back onto aspirin, but with care that she take it with meals, lots of water, and an antacid. Then they began a long, slow process of rehabilitation, which is documented in these photos.

Teresa was improving steadily. Unfortunately, when she returned home for Christmas she fell ill with dengue (break bone fever) and nearly died. Her family stopped both exercises and medication. When she returned 6 weeks later she was as stiff and bent as when she had first come. She was so depressed she spoke to no one, not even her parents. The team began her rehabilitation all over again.

Teresa still has a long way to go before she is fully functional and independent, but she has come a long way. Now she spends an increasin amount of time back in her village with her family. Together with her family, she is taking more responsibility for her own therapy and continued improvements. The village team of PROJIMO have helped her gain new understanding and use of her body, new friends, and a new, more hopeful view of herself.

With the help of the PROJIMO team, Teresa has a new happier outlook on life—and a brighter future.

Latest News About the Hesperian Foundation

The Hesperian Foundation has greatly expanded its activities since the days when it served mainly to support Project Piaxtla. With the experience of Project Piaxtla and the lessons learned from its efforts to promote cooperation between similar groups and programs in Central America, India, the Philippines, and elsewhere, the Hesperian Foundation has taken a leading role in the international rural self-care movement that Where There Is No Doctor helped to spark.

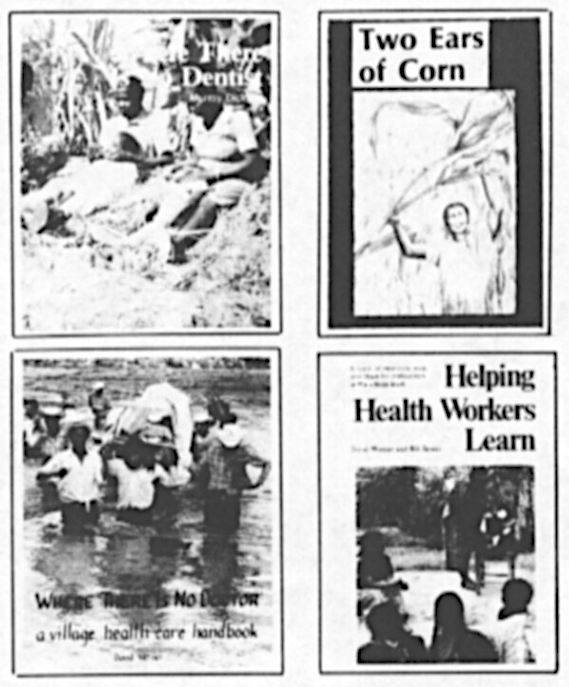

Every month the Hesperian Foundation ships thousands of books, including 2 new titles: Where There Is No Dentist by Murray Dickson and Two Ears Of Corn by Roland Bunch. Helping Health Workers Learn, first available in February 1982, is now in its fourth printing, and we are preparing a Spanish translation soon to be published in Mexico. Independent translations into Portuguese and Bengali are also in progress. 15 slide shows based on Helping Health Workers Learn were introduced in August 1982, and they too will soon be available in Spanish.

At last count, there are 23 versions of Where There Is No Doctor in use in over 150 countries.

David Werner has spend much of the past year writing and illustrating a new book called Rehabilitation of Disabled Children in Rural Areas (a.k.a. Disabled Village Children), based on his experience with Project PROJIMO. Physical therapists are giving him valuable feedback and constructive criticism. Photocopies of the first, experimental draft are available for $10.00.

To cope with the tremendous expansion of our activities, we have had to rely on our most important resource—our friends. Our book distribution is carried out entirely by dedicated volunteers. Volunteers have also been important in another ongoing activity: care of severely disabled youngsters. Trude Bock coordinates the efforts of numerous foster familities, rehabilitation professionals, and volunteer helpers who have attended to 36 children over the last 12 months alone.

Our internal organization is evolving. We now have a paid staff of 6 full-time and part-time workers helping to produce books and run the foundation, which is still crammed into Trude’s Palo Alto home. Although we have grown, we remain a low-cost, informal organization.

Oppose U.S. Intervention

Many of the Central American health progreams we have worked with have come under attack by U.S. supported military governments. Health workers with whom we have worked in Nicaragua have reported great difficulties caused by the U.S.-backed anti-government insurgents. In the interests of health and social justice in Central America, we ask all of those who share our goal of a fairer, healthier society to take a stand in opposing U.S. intervention in Central America.

End Matter

Videocassettes of Health Care By The People

Would you like to buy a videocassette of our film, Health Care By The People? If so, please let us know, and mention what format (Beta or VHS) would be most convenient. Price will depend on the format and the number of orders we anticipate, based on response to this inquiry. If interest is low, we will not produce videocassettes.

We Need Volunteers

We are looking for volunteers to help:

-

pack and mail books.

-

keep the office running.

-

type, word process, paste up, translate and edit the new rehabilitation book

-

care for children who come to the U.S. for medical treatment. The children need foster familities for periods of a week to several months, and transportation to doctor’s appointments.

-

drive children and supplies to western Mexico.

Project PROJIMO needs pediatric physiotherapists, orthotists, rehabilitation engineers, and specialists in sign language to volunteer as teachers.

Fundraising for Our New Rehabilitation Book

Our fundraising priority this year is the new rehabilitation book. We need $48,000 to cover production costs.

The Hesperian Foundation accepts no government or corporate funding. All donations made to the Hesperian Foundation are tax deductible.

End Matter

Please note: Sections and other presentational elements have been added to this early Newsletter to update it for online use.

Note: This Newsletter has been written primarily for the friends of Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation who are already familiar with the history and activities of these groups. If, however, you would like more information about Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation, please do not hesitate to request it.

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |