Mari

EDITOR’S NOTE: Bruce is a quadriplegic wheelchair rider who for years has worked as an organizer, advocate and peer counselor for disabled people, both in the U.S. and abroad. His experience in advising local groups of disabled people in Mexico and Central America makes him a valued guest at Project PROJIMO. This is Bruce’s account of an interaction he had with Mari, one of the PROJIMO workers, during a UNICEF-funded and PROJIMO sponsored rehabilitation course held in Ajoya earlier this year for rehabilitation workers from all over Central America.

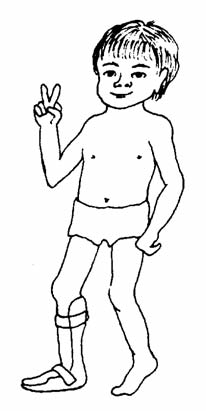

Mari is paralyzed from the waist down from a car accident four years ago. Before her accident she worked full time in a flower nursery. After her accident, she became very depressed and isolated, and twice tried to kill herself. Mari came to PROJIMO two years ago “to learn to walk again.”

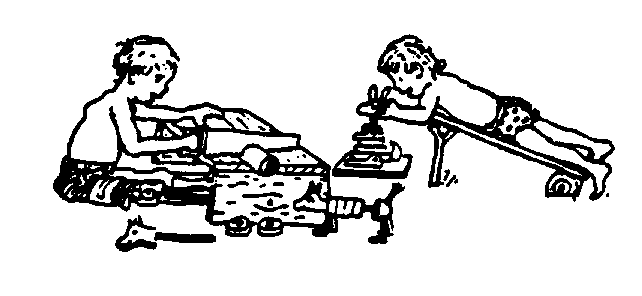

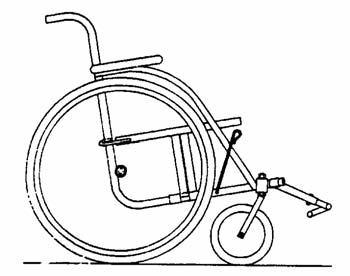

Even though the PROJIMO team warned her that if she learned to walk at all it would only be with the use of braces and crutches, Mari persisted and worked hard at the difficult exercises. Following her accident she refused to use a wheelchair, but while at PROJIMO she began to use a lightweight one that the team designed to meet her special needs. Mari became increasingly involved in the day-o-day work at PROJIMO and soon became one of the most important members of the team. She found she could move around faster in a wheel chair, and so learning to walk became less important to her.

Last January, Mari had a flare-up of an old osteomyelitis (bone infection) in the hip caused by a severe pressure sore that developed soon after her accident. This meant she had to spend most of her time lying on her stomach and could no longer get around in a wheelchair. As Bruce describes, Mari went through a difficult period of accepting this new limitation.

The first time I met Mari was the morning I arrived in Ajoya. I had turned right off the main street, gone between two houses and past the pigs laying side by side sleeping in the sun, to the lower street of the village where PROJIMO is located. There were people everywhere, standing, talking or moving about the dusty playground in the middle of the compound. The sun was very bright and made sharp, well defined shadows everywhere.

Since my last visit over one and one-half years ago, the number of buildings had doubled. There was a huge new one-sided workshop with lots of machinery and several workers were busily banging away at wood and metal, almost it seemed, in a contest with each other to make the most efficient noise possible.

Several people stopped me to talk about my trip to the village, and to ask what I had been doing lately. When I was free from talking for a minute, it seemed a good time to go and meet Mari. Back home during the last few months, many people asked me if I had met Mari, and each time an image of this woman kept growing in my head. She would be a strong, dynamic, highly competent, disabled young woman—a paraplegic whom everyone said was becoming a cornerstone of the Program. Someone told me that her room was the first one in the new model house that had been built next to the big new workshop.

As I crossed the dirt yard, I looked at the new model house. It was a narrow rectangular adobe building, maybe 60 feet long, with three sleeping rooms and a large open kitchen and eating area, all facing front. Many people, some in wheelchairs, some walking one way or another, were busily moving about and there was a crowd of bodies packed into the doorway of the first room. I pushed the front of my chair up against the legs of a tall, middle-aged wan who was holding a small boy’s hand. “Con permiso,” I said gently, as though I had every right to be in the middle of that densely packed room.

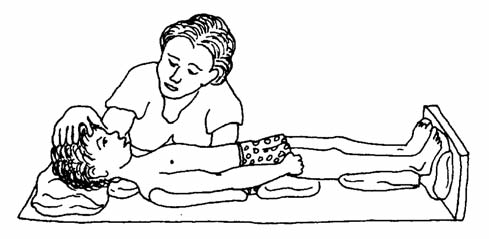

As my eyes adjusted to the deep shadows of the room after the bright sunlight in the playground, I saw people jammed everywhere in a room maybe 10 feet by 10 feet, furnished with two beds and a couple of small chairs. David sat on one bed examining a small disabled girl. The child’s mother loosely held her daughter on the bed, mostly to prevent her from moving abruptly and rolling off. There were other villagers in the room listening to the evaluation of this young child’s body and how the mother might be able to more effectively involve her child in their home life. Some of the villagers listening also had children to be evaluated and in this way maybe learned new ideas for their own children. But for whatever reason, it was clear their attention was totally focused on what David and the mother were saying.

On the other bed was a young, dark-haired woman. She was lying on her stomach with a sheet pulled up to her waist, busily writing notes about what was being said. There were more people crowded on their side of the room too. I decided that this must be Mari, but that it was definitely not the time to come visiting. Maybe after the consulta would be a better idea. So, without saying anything, I stayed listening a little longer, and then quietly pulled myself back out of the shadows of that crowded room that was filled with energy, and I went back into the hard bright sunlight of the playground.

Later that afternoon I returned. This time, when I entered the darker shadows inside the room, Mari was lying on her side, just as other PROJIMO workers were finishing cleaning and bandaging a large, very deep sore on her buttocks. At the same moment I entered, Flor came in with some papers for Mari to sign. Then a young boy came in asking for change for a large bill. Mari reached over to a box from which she took out some smaller bills. “Hello,” I said. “My name is Bruce.” She smiled and finished counting the money. Then she said, “Hello, my name is Mari.”

Soon everyone left, and we began talking about how long she had been in Ajoya, and how long I would be staying. We talked very easily and comfortably because she had a ready smile. Every now and then when we laughed her eyes would sparkle. Often somebody would walk in and Mari would stop and very efficiently handle their request, her eyes becoming harder and more purposeful. When we talked they seemed to reflect a lighter, more curious spirit.

“I heard that you have a bad sore,” I said. “Yes,” Mari replied. “But it is getting better. I’m taking ampicillin for the infection.” She didn’t seem very worried about it. Being curious, I asked, “How will you participate in the meetings? Will you use a gurney?” “No!” she said emphatically. “Pablo is making me a cushion so I can sit in my chair!”

Now I was intrigued, because good cushion foam certainly wasn’t available here, and her sore was so deep it didn’t seem possible that she could sit without doing herself harm. After more discussion, though, it became clear she was going to use her wheelchair and that was just the way it was going to be. So I excused myself and went looking for Pablo and the cushion he and the PROJIMO team had made for Mari.

Pablo was eager for me to see the creation of different foams, angled this way and that, forming a support for one side of Mari’s body while keeping weight and pressure off the other. I tried it out, and with the ability to feel pain and discomfort that I have, I knew this cushion was not going to protect Mari’s sore.

All too well, I also understood that powerful immobilizing fear of what other people will think of us when we go outside into the streets.

“Pablo, I don’t think this will work,” I said, gently explaining that I could still feel pressure against my bones. “Why can’t she use a gurney for the meetings?” Pablo looked at the cushion, shaking his head. “There is no way Mari will use a gurney,” he said. “She has flatly refused, which is why I was making this cushion. We need her to participate in the classes. She is very important to the Program.’’ Pablo seemed convinced. But I said, “She will only hurt herself more and it’s not right for us to help her hurt her body just because she won’t accept using a gurney instead. Maybe it will help if I talk to her about this, and urge her to use the gurney.” Pablo didn’t look hopeful.

I went back to Mari ’s room and waited until there was no one else there so we could talk honestly and without reservation. “Mari, I’ve tried the cushion and it won’t work.” Her eyes wouldn’t accept my words. “You will only hurt your body if you use this cushion and try sitting in your chair.” She buried her head in her arms. I could sense that she knew I was right, but that something else was unsaid in her heart about this. She shook her head and her eyes flashed with fear. “I can’t use a gurney,” she said stubbornly. “I will use my chair, and I’ll move a lot and keep my body off the sore.” I realized that she was afraid but I didn’t know of what exactly. I moved close to her bed and hooked my arm in hers to touch her and show that my seemingly aggressive questions were caring and non-judgmental. “What are you afraid of?” I asked. She didn’t respond, so I tried guessing. “Do you think that you will look strange—more disabled?” She buried her head in her arms, but she held my arm tighter, so I knew it was the right guess. She looked up and nodded in agreement. I paused to think what to do, what I could say that would make a difference.

All too well, I also understood that powerful immobilizing fear of what other people will think of us when we go outside into the streets. This is one of the darkest places in our minds which we are afraid to examine too closely so that we can continue getting through each day. Sometimes there dark fears can be suffocating. We feel alone, trapped in our bodies, convinced that every encounter with another person will be painful for them, for us. We know that people will stare, be curious, and be afraid of the vulnerability we represent. They will avoid us, laugh at us and feel bad for us. But rarely, if ever, will we feel invisible among them, and we withdraw inside ourselves for protection, believing what these fears tell us.

For Mari to go outside on a gurney, even among friends, was another blow to her fragile, recently reconstructed self-image. She believed her fears of what people might think or say, or how they might look at her. She had never left the grounds of the PROJIMO rehabilitation center to visit the rest of the village because her fears told her that she would be strange, different, talked about. Rather than experience this humiliation, she preferred staying where it is predictable, even if limiting.

She told me that just a few months ago she had traveled to Mexico City to present PROJIMO’s work at an international conference, and that two of her closest friends and co-workers had helped her to overcome her fears because they needed her to participate. I figured that if she had had one successful outside experience, maybe she could intellectually see that her fears were controllable.

So I held her arm, because lovingly touching and holding a disabled person is one of the most reas- suring and comforting ways to overcome this fear of rejection. I began talking about my own fears, the dark places in my mind that I have been confronting.

Quietly and intimately, I began. “Recently I have tried to dance in my wheelchair in public places such as a party or night club with a dance band. I am so afraid of how I must look, moving just my arms and upper body. My fingers don’t move so I can’t even use my hands expressively. Yet the way I move to the music feels great and I get so involved in the rhythm and the movement, that I forget people are watching me and my spirit soars so high I can’t help but smile and laugh out loud. The other people dancing see me smiling and see my eyes full of joy, and they accept my dancing with them.

“Yet each time I go dancing I’m always terrified. The darkness of fear swells inside my mind, telling me I’m crazy, it will be a bad experience, and that people will laugh. This fear has never left me. But in time I have learned to control it with the good memories of my dancing, and because my friends who love me give me a lot of support and encouragement. Maybe you can control your fear. Remember Mexico City, you had a good time there, didn’t you?” Mari nodded yes. “The other people accepted you, right?” Again she nodded yes. “So you will use the gurney tonight for the slideshow?” She groaned and buried her head in her arms again. “No, I can’t,” she said. “I will be all right sitting in my chair.” Her eyes pleaded with me to agree that it would be all right to use her chair and not force her to be seen on the gurney.

I realized then that her fear was stronger than any intellectual explanation of how to control it. It seemed best to end the conversation because to continue would have been trying to force her to agree, when I knew that only with kind and gentle persuasion would she feel the support that she needed.

I found Pablo and David outside the new workshop examining the just finished multi-layered cushion. I explained my reservations about Mari using it with her wheelchair. They were concerned, but felt that Mari should be able to try it, especially since she refused to use a gurney. After ore fruitless discussion I gave up and went off to do other things until the next scheduled meeting when I knew Mari would use her chair.

A couple of hours later I went to the patio behind the exercise pool where the meeting was in progress and there was Mari sitting in her chair. I watched for a few minutes. While she was busily writing notes, she was also stopping to shift her weight from side to side, trying to keep pressure off her sore.

The next day at dinner time, Priscilla, who was helping to clean Mari ’s sore, told me that it was now discharging pus and was probably infected. “Do you know how deep that sore is?” she said. “I can stick my fingers all the way in and feel her bone. The bone is totally exposed and now it’s infected. This is very serious. She could die from a bone infection. For her to keep sitting on that sore is plain crazy!”

“Yes,” I agreed. “But what can I do? She’s just too afraid to use a gurney and won’t accept the fact that her sore can threaten her life. That’s in the future. Right now she wants to be in the meetings, so it’s easier and emotionally safer for her not to deal with it now. She can’t feel it and she won’t look at it. No one else knows how dangerous her sore has become and that her refusal to use a gurney will make it even worse.”

Then I thought, why not explain it to everybody? Explain what she is afraid of, that the cushion won’t work and that her sore is getting worse and dangerous! Maybe all together their love for her will not permit her excuses to continue.

As I went back across the playground to her room, I called to Flor and Reynerio to please come also. The room was dark with shadows and people were busy cleaning Mari’s sore. I started explaining the whole situation rather matter of factly in front of everyone, when Roberto walked in and began listening. Roberto is a good friend of Mari’s and had gone to Mexico City with her. He is also the coordinator of PROJIMO.

“…and if she keeps trying to sit on that infected sore, it will only get worse. The cushion doesn’t work.”

Roberto asked, “Mari, why don’t you use a gurney?” Mari’s eyes grew wider. “No, I can’t,” she said. “I’ll stay here in my room!” Flor went over and put his arm around her. “It’s all right,” he said. “We’ll be there with you. No one cares if you use a gurney.”

Mari buried her face while Flor and Roberto continued talking softly to her. They told her it would be fine, that everyone loved her, and that she was needed at the meetings. I felt it was time to leave. Everyone was involved now and Mari wasn’t alone with her fears anymore.

Later that night I came to the slide show and there in the crowd was Mari on a gurney. I looked at her until she saw me and then smiled my happiness at seeing her there. She smiled back. After the slide show finished, I went over to Mari and put my arm through hers. Still smiling, I asked, “Is it so bad?” Embarrassed, she lowered her eyes. “No, it’s fine,” she said. I laughed, lifted her chin up so I could see her eyes, and said, “Good, so let’s go outside to see the movie in the village on Sunday!” Mari’s eyes grew wide while she slowly shook her head. “No, I can’t!”

OPPOSE U.S. INTERVENTION IN CENTRAL AMERICA

Many of the Central American health programs with which we work have come under attack by U.S. supported governments. In Guatemala, for instance, the government looks on rural health workers as subversives and many of them have ‘disappeared’. Health workers in Nicaragua report great difficulties caused by the U.S. backed anti-Sandinista ‘contras’. In the interests of health and social justice in Central America, we urge all those who share our goal of a fairer, healthier society for all to take a stand in opposing U.S. intervention in Central America.

Community-Based Health Care: Health and Rehabilitation from the Bottom Up

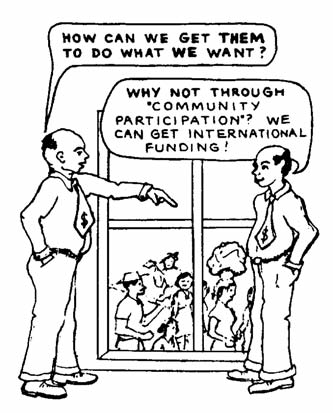

The term ‘community-based’, when used for health programs, has come to mean something different today than it did several years ago. The concept of ‘community based health care’ evolved principally in the Philippines. It has its roots in the Spanish expression ‘comunidad de base’ – essentially a community of working people who find strength in unity and who organize themselves in a struggle for their rights.

Thus, the original concept of community based has a political and egalitarian foundation. It is no surprise, then, given the institutional injustice in the Philippines, that for a time the term became officially taboo and that many programs known to be ‘community-based’ suffered repression.

As so often happens, though, some governments and international agencies co-opted and misused the term. They began to use it, not for programs that grew out of local people’s self-directed action inresponse to urgently felt needs, but for programs that were planned and directed centrally or internationally, and then implanted into poor communities for ‘community participation’ (another co-opted and misleading term).

Because of the present misuse of the term ‘community based,’ some community groups that have organized themselves into programs of self-directed action now refer to them selves not as ‘community-based,’ but as ‘community directed’ or ‘community-controlled.’

Both Projects Piaxtla PROJIMO are organized and run by local villagers. Goth programs believe that a healthier more just society will only come about by the united efforts of ’los de abajo’ -those on the bottom.

The Project PROJIMO Team

Project PROJIMO, run and staffed by a group of 20 disabled villagers in collaboration with the local townspeople, is also committed to a fairer society. The team has come to realize that the low acceptance and lack of opportunities for the disabled in the larger community is but one part of a social structure that mistreats or misuses all who are weaker or different from those in control. They feel that as disabled persons, they must join in solidarity with all who are mistreated, misjudged, or exploited. The struggle for the rights of the disabled is part of the larger struggle for equality and social justice for all the world’s people.

Project PROJIMO, run and staffed by a group of 20 disabled villagers in collaboration with the local townspeople, is also committed to a fairer society.

The quest for a fair social structure needs to start at home. The PROJIMO team has been experimenting, within its own group, with approaches to equitable self-government. But for a group to learn to work together within a framework of trust, equality and shared responsibility is not as easy as it sounds. Some kind of leadership and coordination is needed. In an environment, though, where people are used to a boss/laborer work relationship with its inevitable conflicts of interest, misunderstandings often develop when a group tries to support leaders whose role is to represent the group fairly. After many trials and errors, the PROJIMO team is now trying out a system whereby they elect two ‘coordinators’ (rather than directors), one for meetings and one for activities. Each month they choose new coordinators so that everyone will have the chance (and will recognize the difficulties) of equitable leadership.

Nevertheless, among the PROJIMO team, as within any group, there are certain individuals who have an exceptional ability both for leadership and for human relations. These persons seem to have a skill of bringing people together, of working out difficulties, and of helping the others feel good about themselves and their place in the group. In PROJIMO, Mari is such a person.

Newer and Bigger Responsibilities for the PROJIMO Team

Mari is one of seven spinal-cord injured young persons currently at PROJIMO on a long-term basis. Unfortunately, all arrived with pressure sores, some of them longstanding and life-threatening. Most had developed the sores in the hospital when undergoing treatment following their accidents. By the time they came to PROJIMO, some, like Mari, had already developed bone infections in the sites of their sores.

All this is in addition to the urinary and bowel problems that are common for those with spinal cord injuries. This means that the PROJIMO team has to provide a wide range of fairly continuous services such as nursing and laundry as well as attending to rehabilitation needs. They also produce wheelchairs, therapeutic aids and orthopedic equipment for the hundreds of disabled children who arrive each year. This increased work load has forced the PROJIMO team to seek more effective approaches to teamwork and group monitoring of responsibilities.

Sharing and Spreading the PROJIMO Experience

In the last year the PROJIMO team has been doing much more to share its methodology and technology with other persons, programs, and communities:

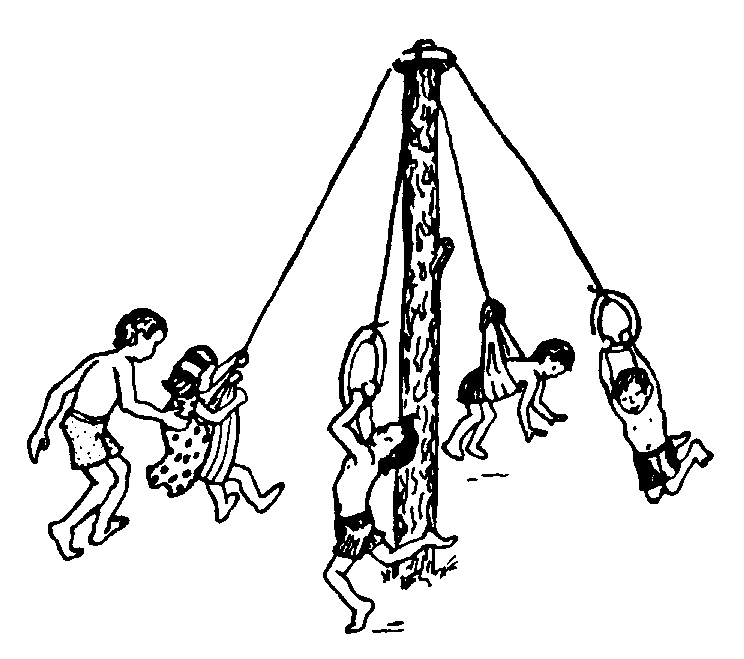

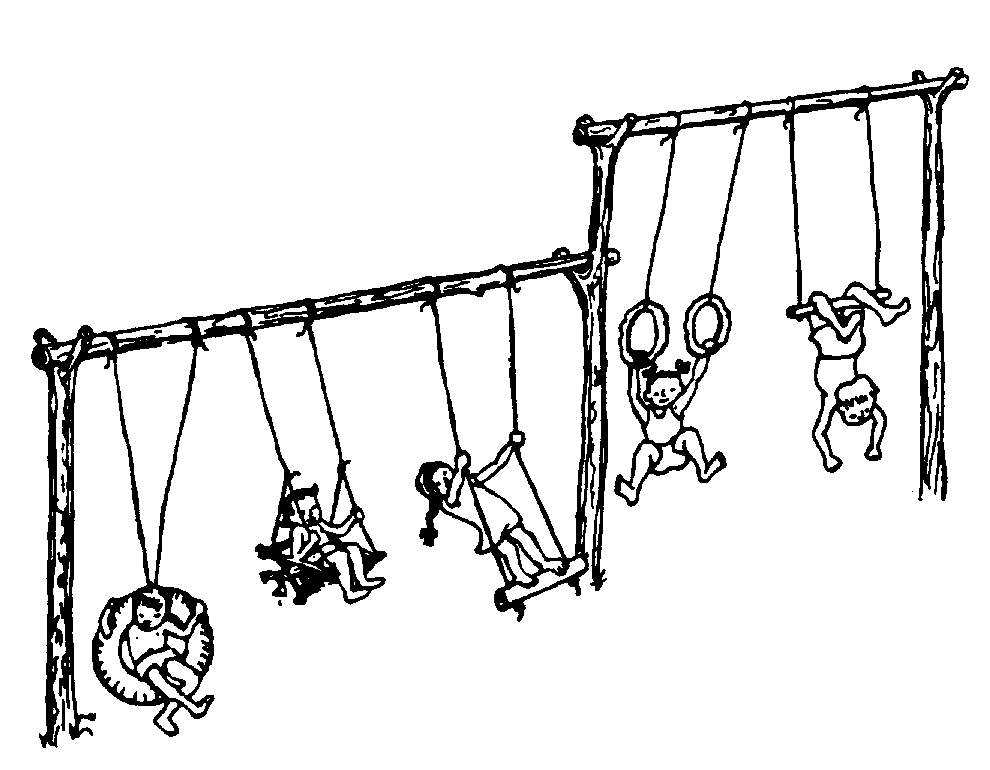

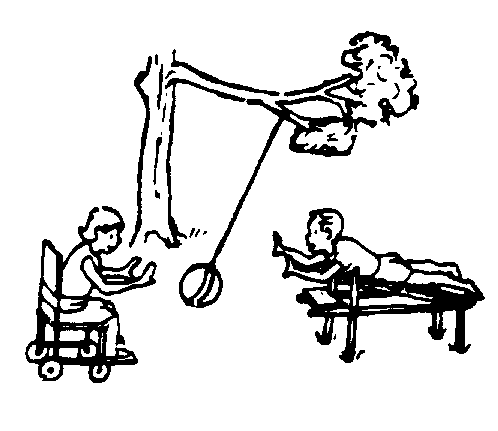

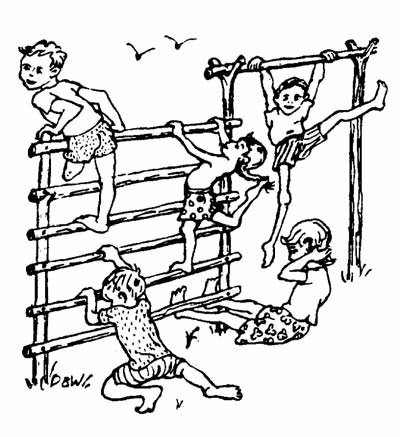

At the local level, PROJIMO has been involved in working with and helping organize families of disabled children in different villages and even urban ommunities. So far, two small ‘satellite programs’ have started in larger towns near the coast. PROJIMO has taken school children from Ajoya (where PROJIMO is located) to these towns where they worked with children and families to set up simple ‘playgrounds for all children’ where disabled and non-disabled children can play together.

Further afield, PROJIMO has reached persons from health and rehabilitation programs in various parts of Mexico, Latin America and beyond to exchange ideas and learn from the PROJIMO approach.

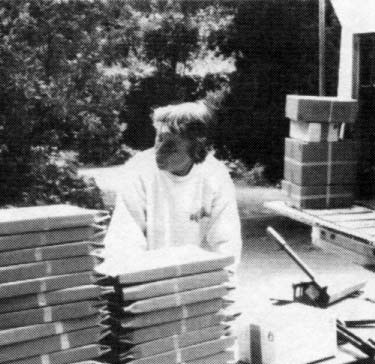

Through a collaborative effort with UNICEF, two 11-day workshops were held at PROJIMO in February and March. Participants came from health and rehabilitation programs in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama, hoping to introduce aspects of the PROJIMO approach, philosophy and appropriate technology into health and rehabilitation programs in their own countries. Taking part in both these workshops was Don Caston, a British engineer who for 15 years has helped design low-cost rehabilitation and therapy aids in African and Asian villages.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is interesting to note that the visitors who seemed to enjoy and learn most from the PROJIMO experience were those working directly with families and children in the communities, or with refugees. For the most part, those holding important positions in urban rehabilitation centers felt out of place in the village and awkward in trying to relate to disabled village workers as equals. The workshop reinforced the PROJIMO team’s commitment to work ‘from the bottom up.’

Apprenticeship opportunity. One of the best ways to ‘seed’ the PROJ IM0 approach community-controlled rehabilitation’ is for the PROJIMO team to accept apprentices (preferably disabled and with strong human commitment) to live and learn with the PROJIMO team. The team feels that the process is as important as the technology.

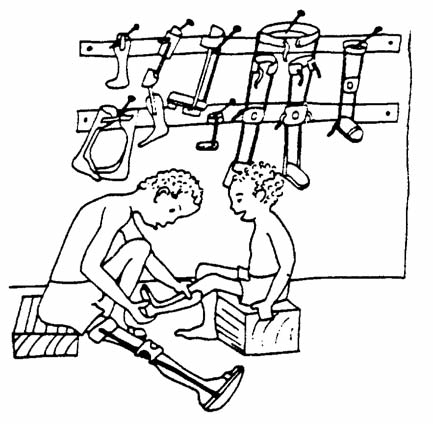

The first outside ‘apprentice’ was Margarito, a young man who is disabled in both legs from polio. He was trained as a village health worker in Alamos, Sonora in a community health program sponsored by Save the Children, U.S.A. Margarito accompanied a child from his home area to PROJIMO who came because he needed braces. Margarito learned to make the braces himself and he returned to his own village to continue his health care work. Like Margarito, a U.S. nun working in Brazil also apprenticed for a few months a year ago.

The newest apprentice with the PROJIMO team is Mario, a young man with paralyzed legs and a mild speech impediment. He was sent by a community health program in Hermosillo, Sonora, sponsored by Project Concern in San Diego. Mario plans to stay three months and then help the Sonoran community program launch rehabilitation activities utilizing PROJIMO ideas best adapted to their own area. (PROJIMO does not feel that its approach should be ‘replicated’ as it is. This is partly because it still has many weaknesses to overcome, and partly because replication denies the participants in each community the adventure of designing their own program according to the unique needs and possibilities of people in their area.)

|

|

|

BECOME A PROJIMO SPONSOR

Through this plan, we invite you to help purchase a wheelchair, leg braces, or basic therapy for a disabled child that can open the way toward a fuller, more independent future for that child. What is more, the wheelchairs and braces are made, and therapy services are provided, at exceptionally low cost by a village team of disabled workers. The team is able to provide a wide range of good-quality rehabilitation equipment and services at costs far lower than those available in the cities:

|

|

|

|

Unfortunately, although the PROJIMO team provides these services at such low cost, a poor family with average earnings of $5.00 a day (when work is available), sees the $140 needed for a wheelchair as a huge expense. The typical family has no savings and is often in debt. Each family is asked to pay PROJIMO what they can, but most can only pay a fraction of the costs of rehabilitation services and equipment, even at the low PROJIMO rates. For this reason, we are asking you to join in an unusual partnership: become a PROJIMO sponsor.

PROJIMO Sponsors are persons who give tax-deductible donations on a regular basis to the “disabled children’s service supplement fund.” These monies, given as donations to The Hesperian Foundation, are not outright grants to the PROJIMO team. They are only used when a poor family cannot pay the entire fee that the PROJIMO team must charge for services or equipment. After the team provides its service, the family pays what it can, and the rest is paid by a “silent partner” – the PROJIMO Sponsor.

Because most of these families cannot afford to pay even PROJIMO’s modest costs, the ever-increasing popularity of the program could ruin it financially, since the team has a commitment to helping everyone in need, regardless of ability to pay. With the “service supplement fund” provided by PROJIMO Sponsors, the team’s ability to serve is allowed to grow along with demand.

To become a PROJIMO sponsor, please write to us and let us know how much you can give regularly to the “service supplement fund.” We are asking for a minimum donation of $120 per year, which can be given in monthly installments of $10, or at any interval you like – please let us know. Of course, one-time donations are welcome, but please understand that because PROJIMO is a continuing program, what we need most is continuing support from persons like you who can make donations on a regular basis. Our three-year goal is to enlist enough PROJIMO Sponsors to create an annual income of $36,000 to the disabled children’s service supplement fund. PLEASE JOIN US!

|

|

|

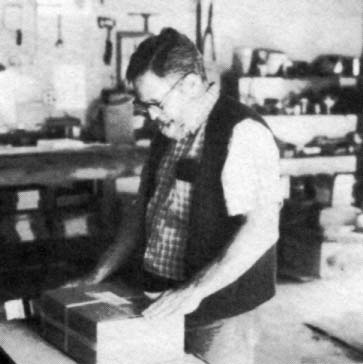

Requests for Donations to Start a Revolving Fund for Independent Income Generation

Many of the young disabled persons who spend time at PROJIMO go home after their rehabilitation with valuable skills they have learned at the Project such as welding, carpentry, leatherwork (sandal making and shoe repair), toy making, sewing and dress making, furniture making and weaving, bee keeping, and wheelchair making. If these young persons could purchase basic equipment to set up their own shops, they would have a chance not only to become more economically independent, but to provide much needed services in their communities. Also, they would give an example to their neighbors that the disabled can learn important skills, become self-reliant and play a valuable role in their communities. They need money, however, to do this.

Polo, for example, who is disabled by polio and uses a wheel chair, is one of the key crafts persons now making wheelchairs at PROJIMO. Because Polo has mastered welding skills, almost every day villagers come to Project PROJIMO and ask him to repair broken equipment such as bicycles, tools, plows, machinery and truck chassis. In this way, Polo has brought about closer relations between PROJIMO and the local community in Ajoya, and a deeper appreciation for the abilities of the disabled. (The able-bodied now come to the disabled for work no one else in town can do.)

Polo enjoys working with PROJIMO, but sometimes says he would like to become independent and set up his own welding shop – perhaps even make wheel-chairs independently.

It would be nice if PROJIMO were able to provide a no- or low-interest loan to Polo and other disabled young persons to set up shops in their own communities. But the Project does not have the funds to do this. We would like to set up tile REVOLVING FUND FOR INDEPENDENT INCOME GENERATION in order to meet this purpose.

As loans are paid back, the money could be used to get others started. Thus, the revolving fund would repeatedly help launch young disabled persons toward economic self-sufficiency. Similar programs in Jamaica and elsewhere have shown that disabled persons who received loans to start small businesses have a better track record in paying them back than the nondisabled.

In this proposal, PROJIMO would like to start small. We are looking for a start-up revolving fund of about $10,000.00. For anyone interested in major sponsorship, we would be glad to discuss further details.

NEWS FROM PROJECT PIAXTLA

Piaxtla, the villager-run clinic, continues to provide a wide range of services for the people of Ajoya and the surrounding, more remote villages and ranchos, despite the continued presence of the free government-run clinic. An unfortunate impact of the government clinic has been to reinforce a dependency among the villagers on unnecessary medications, a custom the Piaxtla team worked hard to discourage, promoting sensible self-care instead.

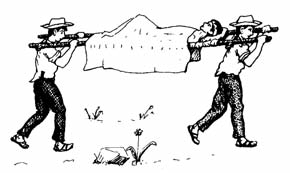

Today, although the Piaxtla team does fewer consultas, their services are preferred over the government clinic’s when there is a medical emergency and someone needs to be hospitalized. Over its 20-year history, Project Piaxtla has developed a good relationship with physicians and private hospitals in Mazatlán and Culiacán who will usually provide free or low-cost services for Piaxtla-referred patients. The government clinic, on the other hand, sends emergency patients to a referral hospital that is farther away and more difficult to reach by public transportation. In addition, the referral hospital provides only a limited range of services. Patients often have to return several times for treatment, and frequently end up not getting treated at all.

The long-term effects of the Piaxtla team’s efforts are impressive. Before Project Piaxtla, 34 percent of all children in the Ajoya area died before age five, mostly from diarrhea and dehydration. Now, only five to seven per cent die. In the village of Ajoya alone, 20 or 30 children would die in one rainy season, when the river water would be especially dirty. Now, thanks to the work of the promotores, most village mothers understand the danger of dehydration and give their children Suero para Tomar (homemade rehydration drink) at the first sign of diarrhea. Only about one or two children die now during the rainy season.

Before Project Piaxtla, 34 percent of all children in the Ajoya area died before age five, mostly from diarrhea and dehydration. Now, only five to seven per cent die.

Similarly, the cause of death of one in ten women used to be a complication of pregnancy or childbirth. With the help of Project Piaxtla, village midwives have learned more about sterile technique, safe management of births, and family planning. With better hygiene and vaccinations in the last trimester of pregnancy, the incidence of tetanus in newborns has been greatly reduced, and more women have safe births and healthy babies. Neonatal tetanus is almost a thing of the past. In the few cases that have occurred, mortality was reduced by having promotores and the mother provide round-the-clock intensive care including feeding the baby breast milk through a nose-to-stomach tube.

One of the most remarkable impacts Project Piaxtla has had is in reducing the incidence of polio in the 5,000-square-mile area the Project serves. The disease is the most frequent disabler of children in the Third World, but in the Piaxtla area, there has been only one (questionable) case of polio in 16 years. In the last three years, by contrast, Project PROJIMO has seen nearly 200 children disabled by polio, all of them from outside the project Piaxtla area. This reduction in polio has been achieved through vaccination programs administered by locally trained village health workers, not by visiting health professionals.

The Mexican government’s rural health program does conduct vaccination programs, but they only visit villages that are reachable by road. At the request of villagers in more remote areas, the Piaxtla team continues to ride a day’s journey up into the mountains to areas that the government doesn’t serve.

To improve nutrition, over the years the team has promoted reliance on local resources such as breast feeding and locally grown crops. Following the lead of the Piaxtla team’s demonstration garden, many families now raise their own crops.

In addition, a recently started program to vaccinate all the chickens and pigs in the area should prevent these much-needed food sources from being wiped out by epidemics every three or four years as they have in the past. The improved nutrition that has resulted from, all this has helped resistance to disease, especially in small children.

Miguel Angel Manjarrez and Miguel Angel Alvarez, who began as village health workers with Project Piaxtla when they were young teenagers, are both nearing completion of their training as physicians. Miguel M., who finished third in his class, is doing his year of government service at a hospital in San Ignacio, and Miguel A., who finished first in his class, is doing an internship at a government clinic in Culiacán. Both men have become valuable resources for the Piaxtla and PROJIMO teams because they return to Ajoya on their days off to share with the village health workers the skills they have learned.

Before coming to Piaxtla, Miguel A. lived in a remote, single rancho where he helped his family raise goats. His medical school class elected him to give the graduation-day address. Miguel, dressed neatly but simply, (all his classmates wore tuxedos), spoke of the necessity for doctors to work both for a modest wage and in rural areas.

NEWS FROM THE HESPERIAN FOUNDATION

While the Foundation remains small and informal, our activities continue to grow. We receive hundreds of letters each year from village health workers all over the world letting us know how useful our materials are to them, and also sharing with us the various adaptations they have made to make the materials more appropriate for the country in which they live and work.

The Disabled Village Children’s Manual, a guide for health workers and families, which David Werner and the Hesperian Foundation are preparing together with PROJIMO is nearing completion of the rough draft. Work in reviewing and incorporating suggestions (from sources all over the world) will take approximately six months. Then it will be typeset and printed. We expect the book to be in print, in English, by summer or autumn of 1986.

While the Foundation remains small and informal, our activities continue to grow.

Slide Shows of PROJIMO with scripts in English should be ready later in 1985.

Where There Is No Dentist is now into its third printing in English. Suggestions for improving the book may be sent to author Murray Dickson c/o the Hesperian Foundation. Spanish and Portuguese editions will be available in 1986.

Helping Health Workers Learn is now available in Spanish and Portuguese. See the enclosed brochure.

Where There Is No Doctor will undergo a. major revision when the rehabilitation manual is completed in order to incorporate many of the suggestions we have received over the years that the book has been in print. Here is a list of the various languages in which the book now appears.

TRANSLATIONS OF WHERE THERE IS NO DOCTOR

| Country | Language and title |

| BANGLADESH | Bengali |

| BRAZIL | Portuguese |

| BURUNDI | Kirundi |

| COLOMBIA | Guajivo |

| ERITREA | Tigrigna |

| INDIA | English (adapted for India) Hindi Telugu Tamil |

| INDONESIA | Indonesian |

| KAMPUCHEA | Khmer |

| LAOS | Lao |

| LEBANON | Arabic |

| MEXICO | Spanish Tzotzil |

| NEPAL | Nepalese |

| PAKISTAN | Urdu |

| PARAGUAY | Guarani |

| PHILIPPINES | Cebuano Hiligaynon Ilongo Ibatan Tagalog |

| SENEGAL | French (adapted for Africa) |

| TANZANIA | Swahili |

| THAILAND | Thai Karen |

| VIETNAM | Vietnamese |

TRANSLATIONS IN PROGRESS:

| BOLIVIA | Aymara |

| HAITI | Creole |

| INDIA | Kannada Marathi |

| ITALY | Italian |

| PAPUA NEW GUINEA | Pidgin |

| PHILIPPINES | Ilocano Maruano Sebuano |

| SOMALIA | Somali |

| SRI LANKA | Sinhala (Lankava) |

| ZIMBABWE | Shona Ndebele |

NEEDS FOR ASSISTANCE

The Hesperian Foundation is fortunate to have a loyal group of friends and volunteers, but further assistance is still needed in many ways:

-

Foster families willing to house, feed and care for disabled Mexican children brought to the Bay Area for surgery. The surgery is provided free by Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children in San Francisco, and by INTERPLAST in Palo Alto. We have a desperate need for more foster families, and unless we find them, some children may go without much-needed surgery. The average stay of each child is about three to four weeks before and after surgery. The U.S. Immigration Service cooperates by providing temporary visas.

-

A coordinator to work with Shriners arid INTERPLAST, and to arrange for foster families. For years Trude Bock has done this, but she needs help. It is a big job, sometimes frustrating, but very satisfying.

-

Drivers willing to help take the Hesperian Foundation vehicle to and from Mexico with disabled children and supplies.

-

Contributions to help cover travel and miscellaneous expenses involved in bringing Mexican children to the Bay Area for surgery (approximately $100 per child). We bring about 20 children each year.

-

Supplies and equipment:

-

tools – hand and electric – all kinds

-

industrial leather sewing machines

-

sheets, blankets, cloth

-

bandages, material and gauze

-

plaster bandage materials for casting

|

|

|

-

Volunteers to visit with Mexican children at Shriners hospital, and to take children on outings” while they are with foster families.

-

Space needed, nine feet by four feet, in someone’s garage, to store three pallets of books, preferably in the Crescent Park district of Palo Alto. Also, we are looking for a modest apartment or cottage in the Palo Alto area for Hesperian workers Paul Silva and Rosa Martinez de Silva. Paul is a rehabilitation worker and Rosa is a veterinarian who coordinated the recent chicken and pig vaccination program in Ajoya.

WHY WE PUBLISH OUR OWN BOOKS

Although the Hesperian Foundation was not established with the intention of becoming a book publisher, the distribution of WHERE THERE IS NO DOCTOR, HELPING HEALTH WORKERS LEARN, and our other materials has become a major part of our work in California. A dedicated group of volunteers answers mail, prepares invoices, and ships books – tens of thousands of books each year. Many books are sent free, but we must charge for most of the materials we ship. The small profit we make from this is used to fund the distribution of free copies, to pay for subsequent printings, and to cover the administrative cost of the Foundation.

Volunteer labor helps us to both meet our financial needs and to offer our materials at below market prices. Sometimes we wonder if it is worth the trouble to process all the orders ourselves, instead of turning our book distribution over to a “professional” book publisher.

Just last month (May, 1985) a publisher approached us and offered to take over all of our book distribution, storage and invoicing. We were told we could eliminate all the bother and still meet our administrative costs since we would be paid a royalty on sales. It sounded good, until we heard what they would charge for our books: $22 to $25 each!

We will continue to self-publish as long as high commercial prices prohibit distribution to the persons for whom our books are written. Our current prices (sliding scale, from $9 to $5 including shipping) have not risen for four years, thanks to the efforts of Barbara Hultgren, Sue Browne, Pat Bernier, Paul Chandler, and the many others who help us with distribution. THANKS!

|

|

|

|

End Matter

Please note: Sections and other presentational elements have been added to this early Newsletter to update it for online use.

Note: This Newsletter has been written primarily for the friends of Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation who are already familiar with the history and activities of these groups. If, however, you would like more information about Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation, please do not hesitate to request it.

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |