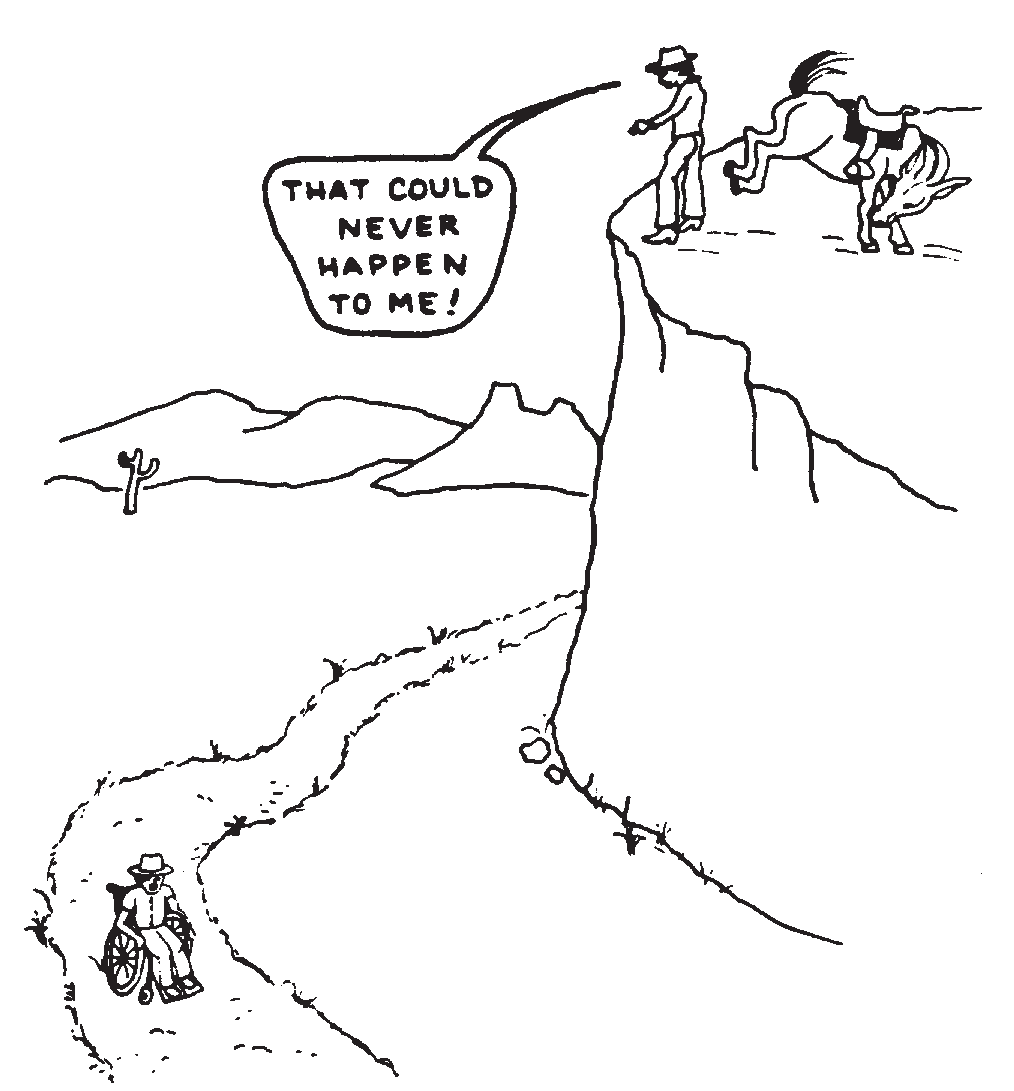

Lupe, The Wildcat

Lupe was a wild little girl. Her two brothers, Paulo and Jorge, were almost as wild as she.

They all swam in the deepest water holes. They swam when the river was running high. Once Paulo was swept a mile downstream before he was caught in a tree half-submerged in the water and was able to pull himself out. It wasn’t long after this that the children began playing with dead lizards. They closed the little gecko’s jaws over their earlobes as earrings and hung them from their lips as monsters’ teeth. When their cousin Julio came from the city to visit them, he was disgusted by their games, so they put a dead snake in his bed. For this they were spanked.

What Lupe loved most of all was the family’s horse. Ever since the day three years ago when they had bought him, Lupe had helped her father brush him and feed him, clean out his stall, and oil and polish his saddle. He was even wilder than the three children. The horse’s name was El Diablo, “The Devil.” He had been badly treated as a yearling and hated most men. But he was gentle with children, especially Lupe.

In the early months of the rainy season, when the ground was soft and the new green plants were still tender, Lupe would take him out to the hills in the late afternoon to play their game. When El Diablo was saddled, he was obedient. But once in the hills, where no one could see, Lupe would take off his saddle and bridle, and they would pretend he was a wild stallion.

He would race about, galloping here and there, sometimes running close to Lupe, but too far away for her to touch. Lupe would stand as still as an owl, only moving her eyes, or she would crouch motionless on a big rock, and wait. At last El Diablo would pause to nuzzle her, with wide eyes, to see if she was still alive. Lupe would leap on his back and hang onto his mane. Pretending to be frightened, the horse would race off across the fields. Then he would suddenly stop, turn round and round, buck and run. He would stand up on his hind legs and paw the air, until he finally threw her off. Lupe would lie in the wet green leaves. Then El Diablo would come up to her and blow his frothing snot all over her face. She would laugh and hug his neck.

All that was before her accident. It happened in November, the year that Lupe was 11 years old, Paulo was 12 and Jorge 8. Their father had gone to the fields to make one last check to see that every bit of corn had been harvested and bagged. Their mother was at a neighbor’s house with their new baby brother, Flor, making empanadas stuffed with squash and brown sugar to celebrate the last days of the harvest. Paulo took their father’s old rifle and the three children walked quietly off to a little rocky valley near the river. This was a place where no one ever went since the day an old woman had drowned in a flash flood. Everyone said her ghost still hid in the crevices between the rocks and trees.

Suddenly she felt a burst of pain in her back, and she was thrown to the ground.

The children came here for secret target practice. They pretended they were a group of small farmers caught in a feud between two powerful drug dealers who were terrorizing the countryside.

You may think this was all from police movies they had seen on television. But Lupe, Paulo, and Jorge had no TV. They lived in a state of Mexico where people could and can make 20 times the money for a crop of marijuana or opium than for a good crop of corn. So, as they do today, many farmers grew the drugs in secret fields back in the higher hills where no one went. The Mexican villagers were too smart to use the marijuana or the opium themselves. They’d sell it to dealers who would sell it in the United States for millions of dollars. The three children had seen the marijuana fields and the poppy fields when they climbed into the higher mountains to gather wood. They had seen young men with their guns, and later with their new 4-wheel-drive pick-ups and deluxe vans. They had heard the shoot-outs in the streets. And they knew it was no TV movie. But now they were playing with their father’s rifle, and their battle was only a game.

The children were using a giant fig tree as their target. Lupe had finished her turn. She had to pee. She saw some bushes off to the side, so she began to walk toward them. Suddenly she felt a burst of pain in her back, and she was thrown to the ground. Thinking that Paulo had pushed her, with fury she tried to jump up to fight him. But she could not move her legs. The numbing pain in her back spread up into her head and made her weak and confused. In a daze she turned over and sat up. Both her brothers were running toward her.

She looked down at her legs. They lay there in front of her body, one crossed over the other. But she couldn’t feel them. They didn’t seem to belong to her anymore. Dizzy with pain, she sat there. What had happened? She noticed that there was a pool of liquid coming out between her legs. The puddle grew on the ground until it came about half way down her thighs, then it stopped spreading and soaked into the dirt. She had peed where she sat, but she couldn’t feel it coming out, or wetting her. She couldn’t feel her legs or anything. A bullet had ricocheted off a rock and shattered her spine. Lupe looked up at her brothers and said nothing.

Lupe’s family took her to the hospital in the city. She lay across the back seat of the bus, with some cloths under her. Her family sat in the seats around her, squashed together, staring out the windows at the dry green hills, at the trucks passing on the highway. No one said a word about the accident.

Lupe was operated on almost immediately. After several hours, a fat man in a white coat came out to the hall where her family sat waiting. He looked down at Lupe’s father with a disgusted look, then motioned to him to follow. Several women in blue cotton coats appeared pushing a bed on wheels, where Lupe lay still as death. Her mother and brothers followed her into a room, as her father went with the doctor to the front desk.

There was an armed guard sitting next to a secretary. The doctor turned and said to Lupe’s father, “The operation is completed. But the child will have to stay in the hospital for three weeks. The bullet cut right through the spinal cord. She’s paralyzed. From the waist down.” The doctor tilted his head back and looked down along his nose at Lupe’s father. “It’s another case of peasant stupidity; you’ll pay for it now by having a cripple on your hands for the rest of your life. Pay here at the desk—the full amount, or the child will not be permitted to leave the hospital.”

The doctor turned and waddled down the hall. He would not see them again. After all, he knew that she would almost certainly die of pressure sores within a year. Most of them did.

Lupe’s father took the bus back to the village to find money. The rest of the family stayed in the hospital and watched over Lupe. The days went by and turned into a week, then two. Lupe was weak and tired, but otherwise she seemed quite well. She talked, and ate and played with her brothers and baby Flor. Her mother changed the cloths under her whenever they became wet. Otherwise Lupe lay in bed, moving only her arms—and her mouth. She talked and ate A LOT.

One day her mother was changing her cloths when she suddenly saw how big Lupe’s belly was. She looked like she was going to have a baby! They remembered that Lupe had not had a bowel movement in over two weeks. What could they do? How could she get rid of her waste when she couldn’t feel anything and had no control over any muscles below her waist? They talked to the nurses, who told them everybody in this condition had the same problems and they would have to work it out themselves.

Work it out? How? Finally one of the nurses gave Lupe’s mother the name of a private nurse, outside the hospital, who as she said, “specializes in evacuation.” Lupe’s mother left the hospital and walked four miles to the unfamiliar address. She returned late that night with the nurse, who taught the family how to help Lupe move her bowels using a greased finger. The following day, 17 days after she had left home, Lupe pooped onto sheets of newspaper laid out on the bed. It stank so badly and embarrassed Lupe so much that she wanted to disappear. Why had this happened to her? She hadn’t done anything wrong. Well, maybe a little, but she had been careful, had kept way back from the target. Would she ever be able to walk and run again? Why couldn’t she just die?

Two days later, Lupe’s father returned with borrowed money and a folding cot. They left the hospital the next morning. Some people noticed them as they walked through the city to the bus station. Lupe lay in the cot, carried by her father and two brothers; her mother walked behind them carrying Flor on her hip. Everything else—their extra clothes, food, medicines—was piled in the cot around Lupe.

The bus drove home over the same roads, with the same trucks and hills passing by the windows. But this time Lupe noticed only that everyone stared at her with pity in their eyes. Or they sneaked embarrassed looks at her when they thought she wasn’t looking. Lupe felt like a funny-looking animal. She snuggled close to her father, who was always the one to joke and laugh and cheer her up. Today he looked out the window and said nothing.

It was evening when they climbed off the bus. They carried Lupe down the street, unlocked the door, and carried her through to the porch overlooking the central patio, where they set the cot down. As she passed through the house, Lupe was so tired she was only dimly aware of how empty it seemed. Her mother’s high carved bureau and cupboard were gone; the clothes and plates were stacked on the floor. The great old table and chairs carved by her great-grandfather, the envy of the whole village, were not there.

Lupe smelled the tortillas and beans her mother was heating from where she lay. She heard her brothers as they played with each other and with Flor, but she was too tired to do anything. She felt so hot—tired and hot. Micho the cat, hopped up onto the bed and purred against her ear. Lupe hid her face in the cat’s soft fur and slept.

For Lupe’s mother, the garden in the patio was a great joy. As Lupe lay in bed and looked at the same little garden, she began to hate every one of the plants that sat there in the sun, unmoving caged creatures like herself. She especially hated a tree of huge red poinsettias, which seemed to blaze out like burning tongues licking into her brain. Her head, her whole body was burning up with fever. It had begun the day she returned from the city and now, a week later, broke out every afternoon.

A woman in the village came to the house. She was a healer, a person who knew about medicines and took care of the women and children. When the healer turned Lupe onto her stomach to give her an injection, she saw a large patch on her bottom, at the base of the spine. After examining it carefully, the healer took Lupe’s mother to the other room to cheer her up.

“Estela,” she said. “Your daughter is very sick. I have seen something like this twice before, and both times the people died. Her skin is rotting inside her because she cannot move and the bed is pressing against her.” She put her arm around Lupe’s mother’s shoulder. “But I know of a place where you can take her—a place for disabled people like Lupe, where she will be taken care of and where she will be with others like herself. It is in a village not too far from here. And it is run by people who are disabled themselves. I’ve been there. My nephew, son of my sister, is there now. Estela, take her to PROJIMO.”

After the healer left, Lupe’s mother went in and sat on her daughter’s cot and looked down at her as she slept. How she had changed in those few weeks. How the whole family had changed! This little girl who had been so lively, who was always laughing and talking and moving like a restless river, now lay there day after day and stared out at the garden. Everyone did what they could to amuse her. Her friend Ana still came every day to talk with her, but she kept getting sadder. The day before, Lupe had told her mother, “I want to die. You’ve had to sell everything because of me, even El Diablo. Just let me die. You can have another baby who’s whole.”

Lupe was eating almost nothing now, and was gradually growing weaker. She seemed to hate the whole world. The only time she moved her arms was when Micho jumped onto her bed and purred down onto her neck. Then Lupe would hug the cat, and cry.

But would PROJIMO help? The surgery had done nothing to help, and it had ruined them. Maybe Lupe was right. Better wait a day or two.

But the next day when Estela was changing Lupe’s cloths, she saw that the dark patch on her bottom had turned into an open sore. The flesh inside looked gray and dead. Estela washed the area, the dead flesh fell away leaving a deep hole. There was a mass of black stinking goo where healthy flesh had been.

Lupe lay silently as her mother cleaned the sore. It didn’t hurt at all. She couldn’t feel a thing. But she could smell.

Estela was frightened by what she saw. She must get help for her child. She must take her to PROJIMO.

Lupe was hardly aware when her father carried her onto the bus, changed to another bus and yet another, and finally carried her through the streets of the small village of Ajoya. She heard a gate squeak as it opened, heard her father talking with some people, heard her name mentioned several times. But it was all dulled, as though it were taking place in another world. She felt herself being put down in a chair of some sort. But she kept her eyes shut, refusing to be part of it all.

Then she heard a woman’s voice, much closer to her this time, say, “Hello, Lupe.” She opened her eyes.

She found out later that this was Mari. What she first saw was two almond-shaped eyes looking straight across at her, two almond eyes in a pale face surrounded by lots and lots of curly brown hair. And below the eyes, the mouth was smiling with pleasure.

Lupe had not been feeling very happy in the last few weeks. And she was not feeling any happier now. But when she saw Mari’s face, she wasn’t just unhappy. She was furious!

Partly this was because Mari wasn’t smiling at her with pity, as everyone else had done since she was shot. Mari was smiling with pleasure, even joy, as though this were a normal day, a normal meeting, as though Lupe were a normal healthy girl and not a cripple. Lupe had gotten used to thinking of herself as a pitiable thing. She pitied herself, and she expected the rest of the world to do the same.

There was another reason Lupe was angry. As she was staring at the smiling face, she realized that the young woman was sitting in a wheelchair, that the woman was crippled yet acting normal. She also realized that she, Lupe, was also in a wheelchair facing her. And all around them in a large open courtyard were people on crutches, or in wheelchairs, all going about their business here and there. Lupe had no desire at all to be there. She hated cripples. She hated the world. She wanted to be whole, and riding El Diablo. She wanted to be dead.

Mari burst out laughing. “You’re just as wild as a little tiger, like I was when I first came,” she said

What angered Lupe most were the woman’s eyes. Not only because they smiled, but because the woman was wearing pale blue eye shadow on her eyelids, as though she still considered herself a person—as though she still considered herself a woman. You think eleven-year-old girls don’t notice such things or have such sophisticated thoughts, but they do. Lupe was so furious that she wanted to scream. She wanted to punch the face and the whole world. She did the only thing she had strength for: she spit right at the woman’s eyes.

Lupe’s parents were horrified, but Mari burst out laughing. “You’re just as wild as a little tiger, like I was when I first came,” she said. “Let’s take you over to the clinic now, though, and take a look at your sore.”

Lupe gave up. She lay back and closed her eyes. People could do whatever they wanted with her. She didn’t care. She felt herself being wheeled through the courtyard, felt the hot sun change to shade and heard the rumbling of the wheels change to a soft rolling hiss. She was lifted off the chair and laid on a bed.

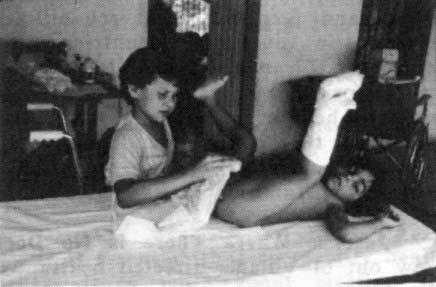

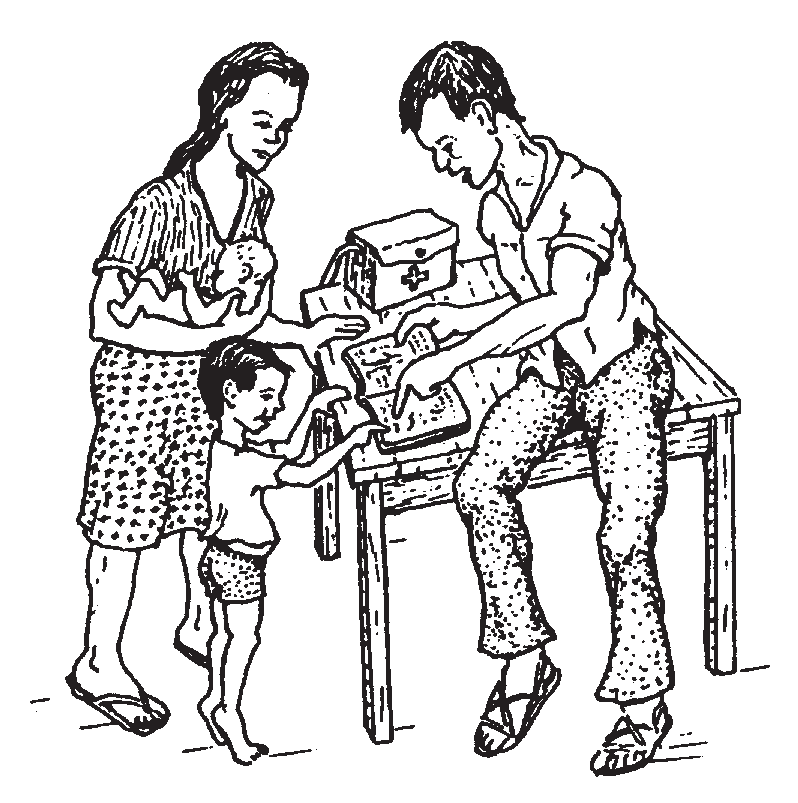

Then Mari and a young man named Manuel began to examine her bedsore. It wasn’t pretty, and it smelled even worse. The dead flesh was mixed with pus and blood—black blood, no longer rich and red—all in a soft mass. Mari put on a pair of plastic gloves and began to clean out the sore with little squares of gauze taken from inside folded paper wrappers. She cleaned out as much of the rotten flesh as she could. At the bottom of the sore, the white bone could be seen. Mari held out some clean pads for Manuel, who poured a brown liquid soap onto them. She washed the inside of the bedsore with this, all around the bone and deep down under the edges of the skin as far as she could reach. The pressure sore extended from under the skin, and was about 5 inches across. It was not very deep, because the bone was so close to the surface.

After the sore was cleaned, Mari swabbed it with distilled water while Manuel walked himself on his crutches to bring the big plastic pot of honey. He spooned out gobs of honey on to the gauze squares that Mari held out to him. Mari then stuffed them into the hole and covered them with a bandage, which Manuel taped down.

Honey? Yes. Honey is better than almost anything for keeping out infection and for helping fresh skin to grow at the same time. Did you ever see mold growing on honey?

The pressure sore would be cleaned and packed again in about 12 hours, but for now, it was time to rest. Lupe kept her eyes shut against the world and slept.

When she woke up, Lupe saw her mother, sitting beside the bed. Her father and brothers were gone. They must have gone back home. Lupe was still lying on her belly. She remembered at once that she was at some place called PROJIMO, and she remembered that woman’s eyes. What a strange place this was, with people so… so… alive! As soon as the word came to mind, it brought all her anger back with it. Lupe’s life was finished. Done. Over. She glared at her mother, closed her eyes again, and shut out the world.

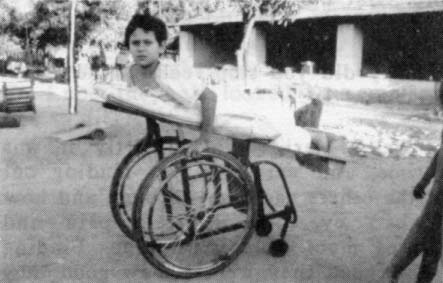

After a week, Lupe’s mother went back home, leaving Lupe at PROJIMO. Other people in PROJIMO tried to make friends with her, but she kept to herself. And so it went. Every day her pressure sore was treated. She was fed and cleaned and dressed. She spent most of her days on a gurney, face down to keep the pressure off her sore. The gurney, which a young man in a wheelchair, named Polo, had specially made for her, was a narrow sloping cot on wheels. The front had big bicycle wheels, so that she could push it around herself.

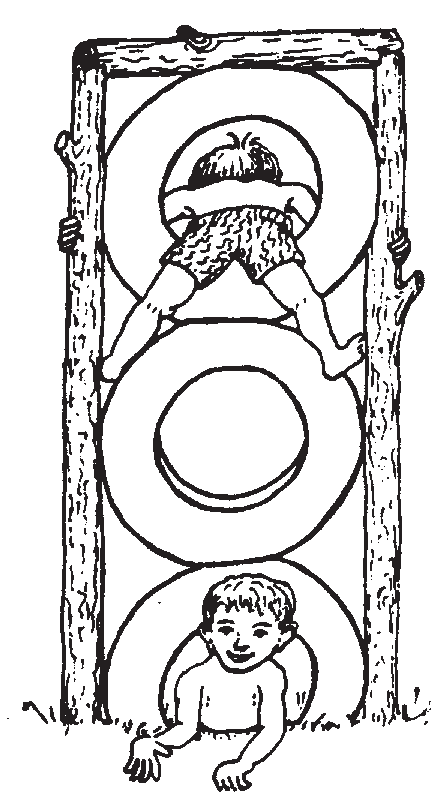

Sometimes she would wheel herself out into the courtyard, where she would watch the children playing on the swings and the jungle gym, or practicing how to walk between two bars. In the afternoons children from the whole village would come to play there because the playground was so much fun. They especially enjoyed the three rocking horses made from big tires, with sticks stuck through for their heads and horizontal sticks stuck through for the children to rest their feet on. All three horses were suspended with rubber inner tubes from tall poles.

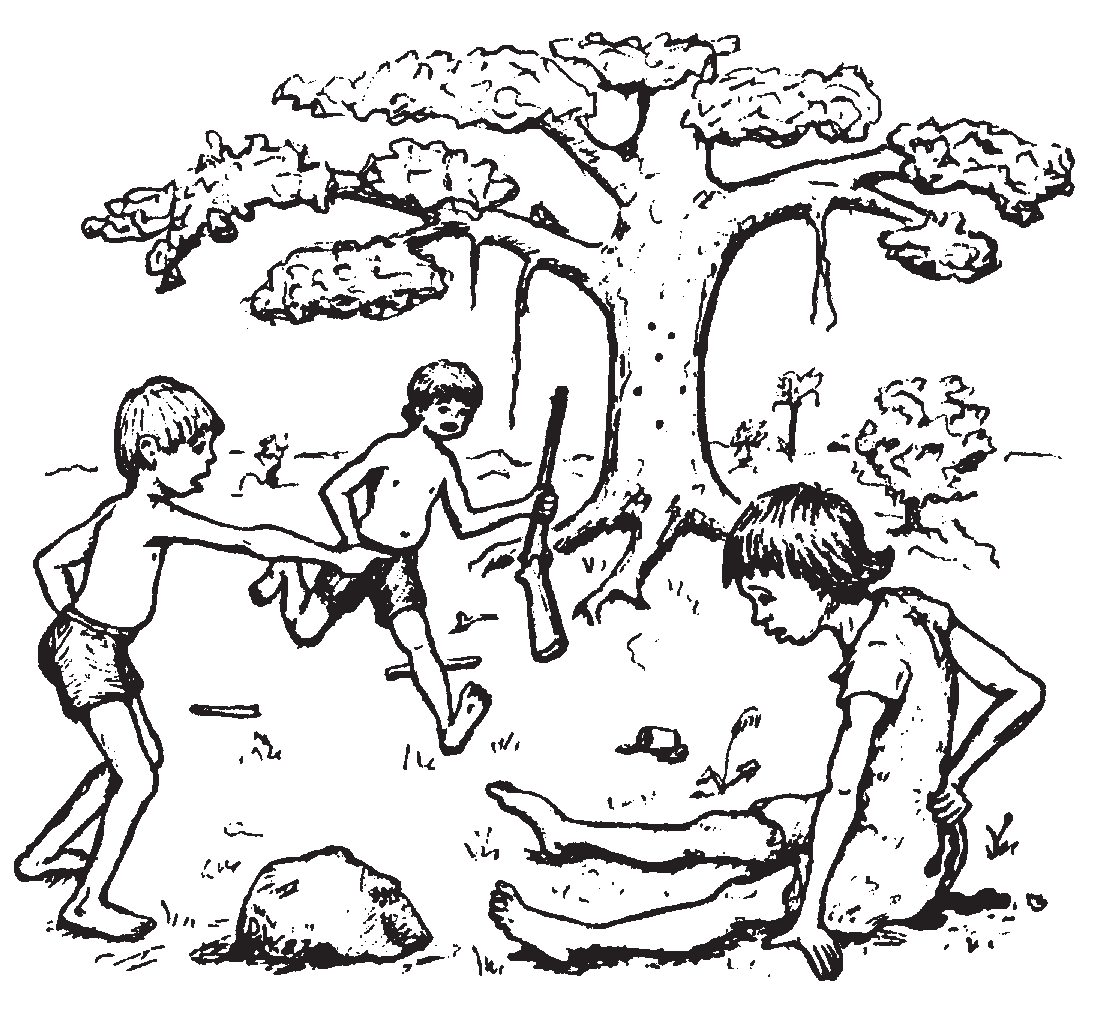

Lupe tried to look anywhere except at the horses, but her eyes drew her back. Her eyes also drew her to Mari as she darted on her wheelchair from one part of the courtyard to the other. Sometimes Mari would look at her and wink. Lupe would scowl and glare at the ground. Or she would look at Conchita as she hung out the laundry. Or at Catalina and Miguel folding paper around the gauze squares they had cut, (which they prepared every day for sterilization in the pressure cooker in the kitchen). Sometimes Lupe watched when other people’s bedsores were being treated.

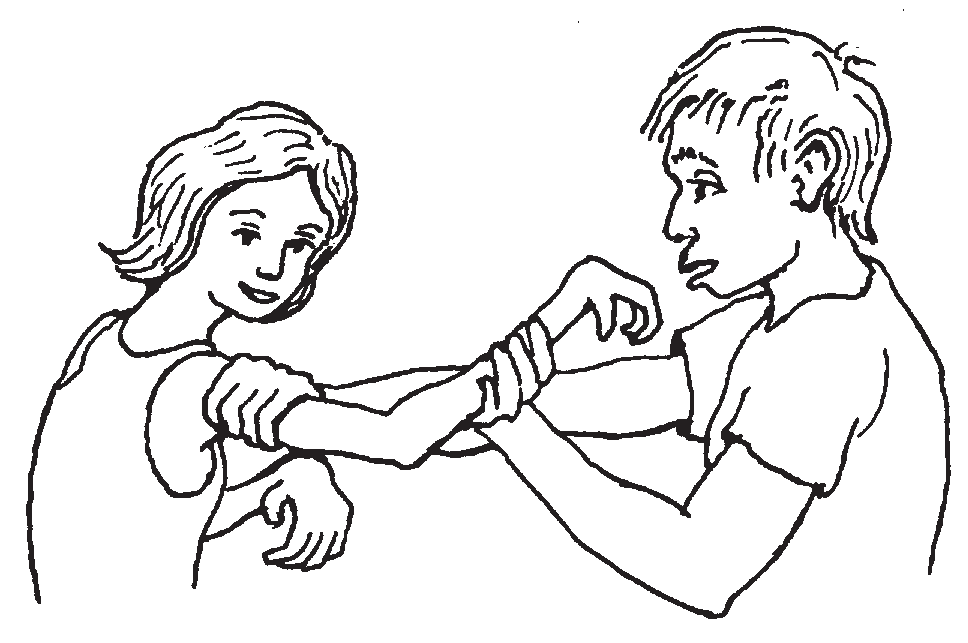

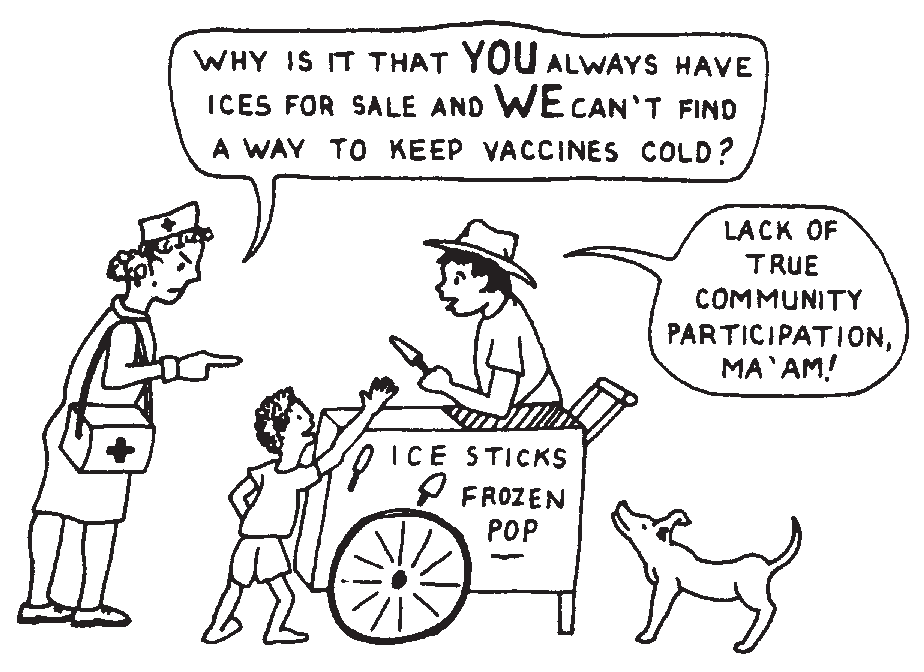

She also watched the exercises. Many people at PROJIMO had disabilities like arthritis or paralysis or cerebral palsy that could cause their muscles to shorten and joints to stiffen in bent positions. To prevent these joint contractures their legs and arms needed to be used and their joints stretched every day. Those who had use of their arms would help the others, and be helped in return.

Today, Lupe watched as Manuel strapped Julio onto a long board, then tilted him up to where he could stand for an hour while his legs stretched. Julio took a long puff on his cigarette, and looked over at Lupe.

“Before long you’ll be stretched out here too, like a mummy, Lupita,” he said, laughing.

Lupe wheeled herself away from him. “I don’t care! I’ll be dead anyway.”

“Oh no,” countered Julio. “As soon as that bedsore of yours is healed, we’ll strap you in like a worm in a cocoon and tickle you under your chin. Then you’ll see how much life is left in you.”

Lupe could not control her rage. She wheeled herself over to Julio and dug her fingernails into his face before he could raise his one free arm to fend her off. “I’ll scratch you worse than that if you ever try,” she yelled at him.

Julio giggled so much from this that he started to cough. The others standing around all laughed and told Lupe she was a devil and a wildcat.

“Hateful bunch of people!” she yelled at them. “I hope he coughs all night and keeps all of you awake.” She spun the gurney around and wheeled herself to her room as fast as her thin arms could make it go. She made sure neither of her roommates was there, and burst into tears. Lupe sobbed and sobbed, not because of what Julio or the others had said, but because her whole body was so full of sadness.

She cried for a long, long time, until the pillow was sopping wet and she had no more strength left to cry. She lay with her eyes closed, as smells of baking tortillas and frying onions and beans came into the room. Her stomach growled. She opened her eyes—to find Mari sitting there smiling back at her.

“It’s good to cry, isn’t it, Lupita?” she said. “I used to cry every day. Every day. For six months there wasn’t a day that I didn’t cry. And I hated the world, and everybody in it, too, day after day after day. Then, do you know what? I found out that everybody here at PROJIMO had felt the same way. They had hated the world. They had all felt that their lives were over and they had all wanted to die—just like I did.” Lupe stared at her.

“You wanted to die too? But why are you always smiling?”

Mari laughed. “That’s how I feel right now,” she said. “Now I feel that my life is a fight, and every day is a new fight, and more precious than the day before. But I used to feel sad and angry, just like you.”

“Why did you stop feeling like that?” Lupe asked.

“Well,” Mari replied. “Partly it was just time, and partly it was finding out what the others had been through and how they had overcome horrible pain and hardships, much worse than mine. Finding out how good they were—how good they are. Partly it was learning to love them, learning to accept their love for me. And maybe the best was finding out that I could help other people -that I had something to give them.”

Lupe scowled. There was no way she could help anyone, lying on this gurney all day. And anyway, she wouldn’t want to help any of them, the way they had laughed at her.

“I bet you think you can’t help anybody, the way you are now,” Mari said. “But you can do all sorts of things. You could get a broom and sweep the courtyard, for example. It’s filthy.”

“Sweep?” said Lupe. “That’s not helping anybody. That’s just stupid. Let those others sweep up their own messes.”

Mari shook her head and sighed. “I remember those days…” she said. “I was a little tiger, just like you.”

Lupe stared back at Mari with her eyes closed to slits. Then she cracked her mouth up, just a bit—the first hint of a smile in four months. “I’m a wildcat,” she said. “You’re a tiger.”

Mari laughed. “Well, how about some lunch, sister cat?” she said. “My stomach’s growling like a lion.”

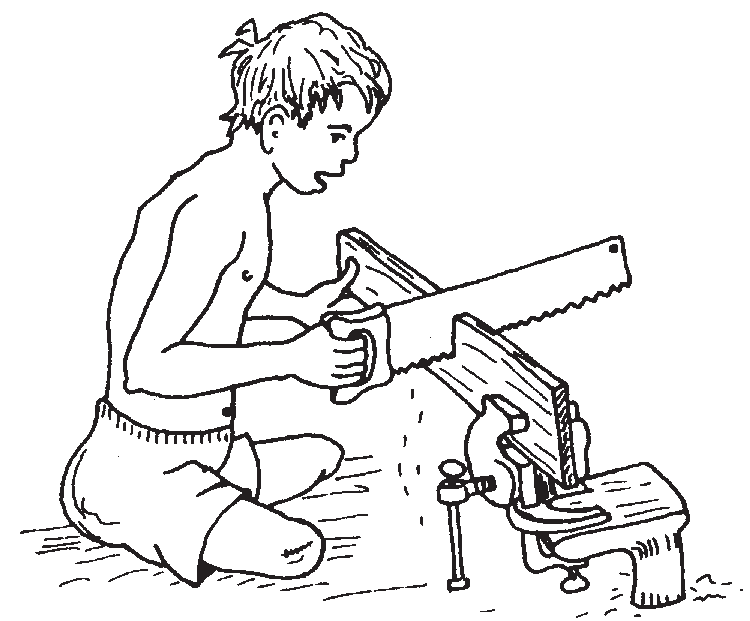

Over the next few days, Lupe watched the others as they worked, exercised, or rested. She wheeled herself into the workshop to watch Felipe and Jorge at work making leather sandals with soles from old tires. She watched Polo making wheelchairs from bicycle wheels. She watched Conchita and Manuel cut out wooden toys and paint them. All these activities brought money into PROJIMO. To Lupe they all looked so complicated, and so difficult.

Lupe wheeled herself around and watched the pigs run through the courtyard. She watched the chickens scratching in the dirt near the garden in the mornings, and in the evenings she watched them fly up into the mango tree to roost. She looked down at the dirt under her gurney, where a long line of leaf cutter ants trod a furrow into the dry soil. Each ant held aloft a bit of green leaf which waved about as the creature made its way along.

“Why is everybody so busy?” Lupe wondered. “Why does everybody show off their stupid abilities and wave them around like chewed up leaves? It’s all so stupid, stupid, stupid.”

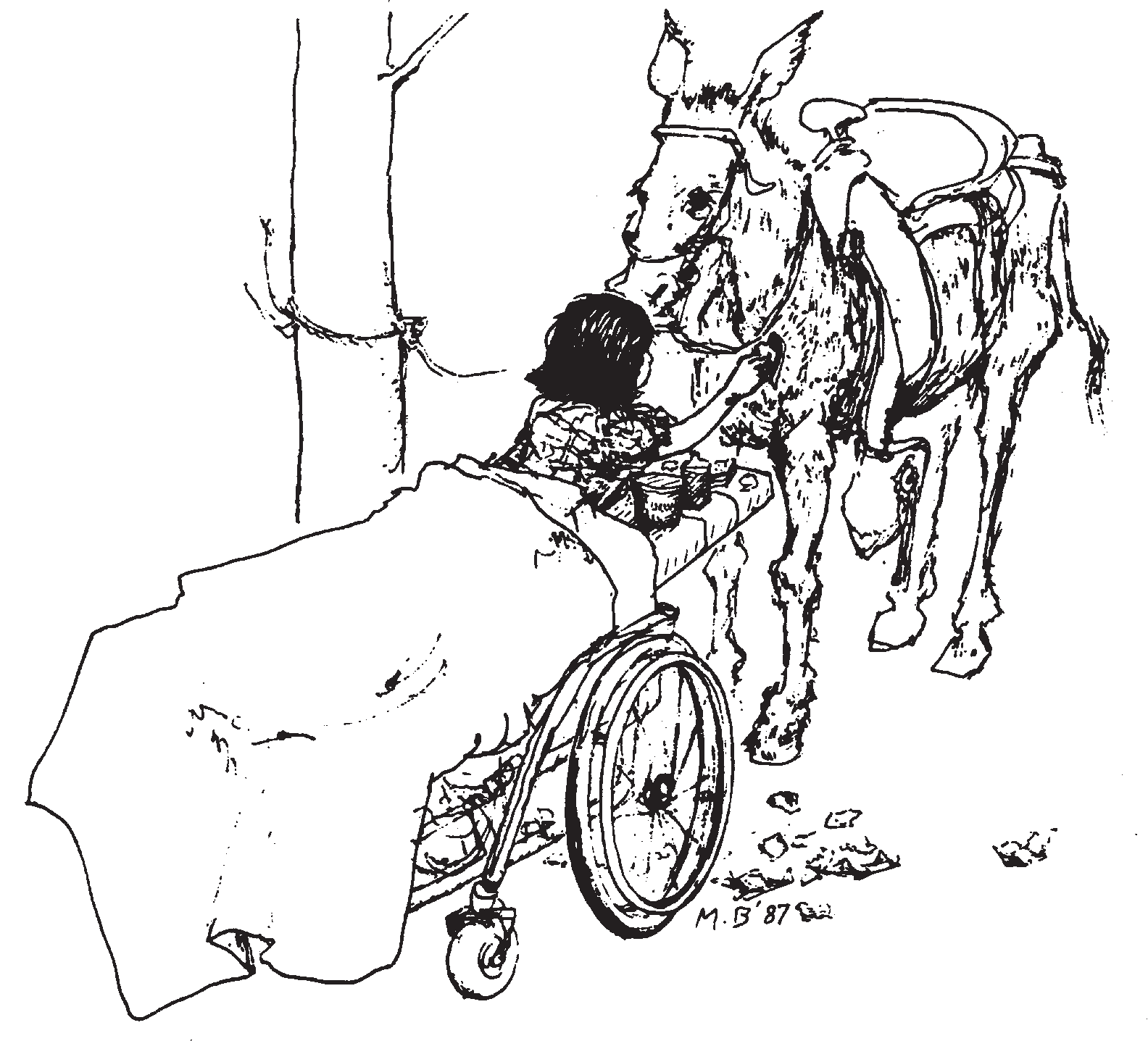

She pushed the bed away from the ants and rolled over to the entry gate. There she stopped and looked out at the empty street and at the closed wooden door across the way. She dozed, until she heard horses’ hooves on the street stones. A young man rode up to the gate, opened the latch, and dismounted, leaving the donkey tied up right next to Lupe. Lupe recognized him as Jasmine’s brother; he rode down from the mountains about once a week to see his sister. Lupe watched him walk off, then returned her eyes back to the donkey, and lay gazing at it.

“You sure aren’t El Diablo,” she said to the donkey. “You look more like an old sweater the moths have been munching on. Dusty on those trails, huh.”

She reached up to stroke the donkey’s muzzle, when she noticed a big festering sore high on the animal’s leg, up near its chest. The wound was badly infected and oozing. Flies crawled on it and buzzed around Lupe’s hand as she stroked the donkey’s neck. She looked carefully at the sore. Then she suddenly whirled her gurney around and wheeled into the clinic, over to where the supplies were kept. Lupe took down several paper packets of gauze from the low shelf, the bottle of brown liquid soap, a bottle of distilled water, adhesive tape, and the pot of honey. But where were the plastic gloves?

Five-year old Antonio, who had come to PROJIMO for correction of his clubbed feet, walked into the room. “Antonio, where are the plastic gloves?”

Antonio pointed to a high shelf.

“Could you get me a pair?”

Antonio pulled a chair over near the shelves, climbed up, reached into the box and pulled out three gloves, which he proudly handed down to Lupe. Lupe gathered all the supplies next to herself, behind the pillow so they wouldn’t fall off, then spun her gurney around and rode back to the donkey.

She carefully put on the gloves, just as she had seen Mari do. She poured some soap onto a gauze pad, and washed all around the sore, swabbing the pus and dirt away. The donkey trembled, tried to back away, but she held its reins with her left hand and talked to it calmly while she worked. It stood quietly and accepted the treatment, only trembling when she dug particularly hard.

When Lupe had cleaned out as much pus as she could, she poured water onto new pads and cleaned off the soap. Then she dried the wound with fresh pads, dropping the used ones all around the gurney. She pulled the bottle of honey from under her pillow and tried to pull the lid off, but it wouldn’t come. There were too many things on her gurney, and the container was too big, too hard to

handle. She lay her head on it and tried to pry up one edge, but her hair stuck to it. The top wouldn’t budge. She tried to pry it off with her teeth, but all she got was a taste of honey and a sticky face. Lupe started to sweat and curse under her breath.

“How about if I open it, Doctor?”

Manuel stood there next to her bed, his arms held out to her from his crutches. Lupe’s heart sank. Now, she thought, he would take over, or he would laugh and tease her. She held out the plastic container. Manuel opened it and gave it back, then just stood there, waiting. Was he letting her do it?

Lupe hesitated, then scooped out some honey, wiped it onto a white square of gauze and held it against the sore. Then she realized that she couldn’t both hold it and cut the tape. She looked up at Manuel. Manuel picked up the tape, cut a strip and stuck it across the pad and onto the donkey’s hair.

“Next time,” said Manuel, “we’d better shave some hair off first.”

“Next time?” thought Lupe.

She spooned out another scoop of honey, held the pad against the donkey, and Manuel taped it down. Finally, Lupe took one more pad and opened it to place it over the whole sore, and Manuel again taped it in place. The two surveyed their work and looked at each other. Manuel held out his hand and solemnly shook hands with Lupe, sticky glove and all. Suddenly Lupe heard a funny slapping sort of noise. She turned. Everyone around the courtyard, was clapping for her.

“Well done, Lupe!” “Good job, Doctor Lupita!” “Next time I have bedsores, I’ll come to you!”

Lupe blushed bright red as she took off her gloves and dropped them on the ground. But suddenly there was Mari beside her, with a broom in her hand.

“Okay, Doctor Wildcat. No throwing away gloves like that; we have to wash those and then sterilize them so we can use them again. And remember how you told me that sweeping was stupid? Well, look at the ground. Whose mess is this? You’ve strewn your lovely flower petal swabs of pus and soap and donkey blood all around your poor patient. I’ll hold the dustpan for you.”

As Mari held the dustpan for her, Lupe swept, her eyes shining and her mouth pulled down to keep from showing how happy she was.

“I treated the donkey,” she thought. “I did it! I did it! Mari is working with me; Manuel worked with me. I can do it. I can do it.”

Mari took the broom and full dustpan in her left hand, and with her right hand she shook Lupe’s hand. “Welcome to PROJIMO, partner,” she said, and wheeled off.

Lupe stayed at PROJIMO for a little more than four months. During that time she took responsibility for cleaning the bedsores of a little girl called Jésica. Jésica had become paralyzed when she was a baby, from an injection that became infected. Every day Lupe also helped Jésica with her ‘bowel program’, using a gloved, greased finger, in the same way the nurse had taught her mother to do for her.

Every two or three weeks, when her family came to visit, they were amazed at how much stronger she had become, how happy she was becoming, and how much she had learned. She was almost like their old Lupe again, but a Lupe wise beyond her years. And more determined. The moment anyone tried to help her, in any way, she would firmly push them aside and do it herself.

The complete version of Molly Bang’s story, ‘Lupe’ is available from HealthWrights. In the future, we are hoping to produce it as an illustrated children’s book—perhaps with a special edition hand-colored by the disabled children at PROJIMO.

Lupe is a composite of several disabled young people at PROJIMO. Almost every event, from the shooting accident, to the experience in the hospital, to her adventures doctoring the donkey, actually happened.

The second half of the story follows Lupe’s return home, her struggle to gain acceptance in the community, and to get into the village school. It also relates her attempts to promote oral rehydration therapy and care of children’s teeth—ideas she picked up while at PROJIMO.

The publication of Molly Bang’s story is covered in Newsletter #46.

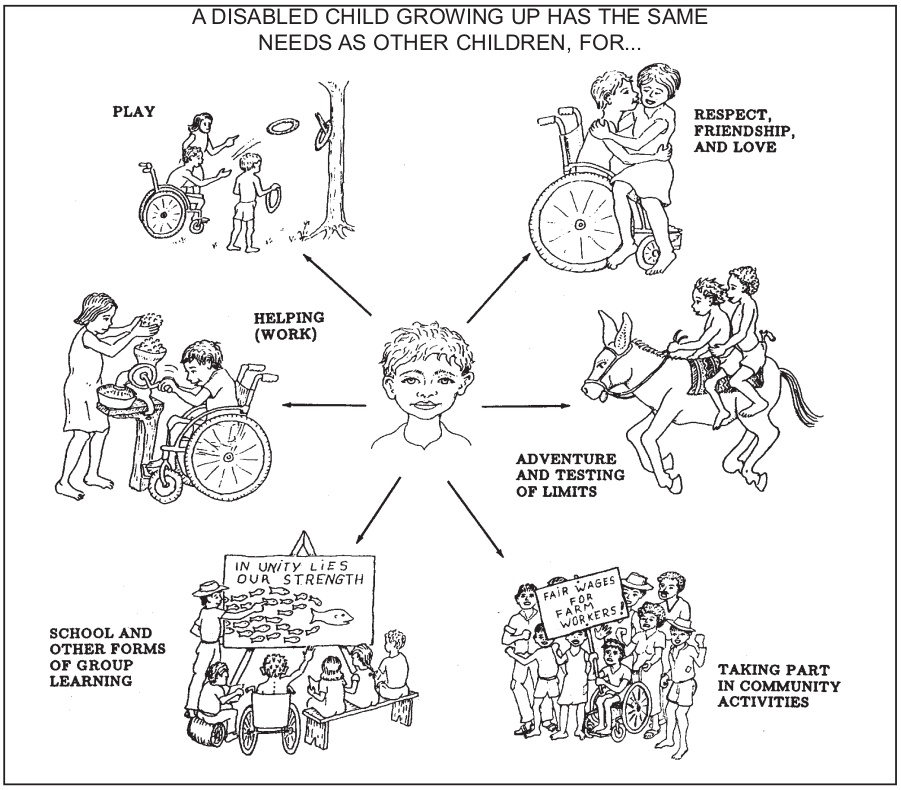

A New Book Published: Disabled Village Children

After nearly five years in preparation, and following extensive field testing and feedback from rehabilitation workers in over 20 countries on 6 continents, Disabled Village Children is at last in print. Written by David Werner with the help of many field workers and specialists, the book is intended for use by community health workers, rehabilitation workers and families.

Just as Where There is No Doctor grew out of villager-directed health work in the mountains of western Mexico, Disabled Village Children has grown out of Project PROJIMO, the pioneering effort of disabled villagers to create a rural rehabilitation program to serve disabled children and their families.

Project PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) is the younger ‘sister’ of Project Piaxtla, the villager-run primary health care program that is now in its 23rd year. In the early years of Piaxtla, some of the health workers selected by their villages happened to be disabled. As the years passed, some of these disabled persons proved to be among the best health workers.

Participation in the health work brought them from a marginal to a central position in their communities. As a result, they tended to work with greater compassion and commitment than most of the able-bodied health workers. In time some of the disabled health workers including Roberto Fajardo, who is now a key figure in both Piaxtla and PROJIMO—became leaders of the primary care program.

Project PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) is the younger ‘sister’ of Project Piaxtla

These disabled health workers became concerned that they knew very little about meeting the needs of disabled persons, especially children. Adding to the problem, the prices in the cities of braces, wheelchairs, therapy and other necessities for disabled persons were too high for the villagers to afford. The cost to get a child with polio walking would economically ruin the child’s whole extended family. Also, the health workers would often see a child who had begun to walk with braces (calipers), go back to crawling. Why? Because the family had spent half their years earnings for the child’s first braces and simply could not find the money to replace the braces each time the child outgrew them. Also, most orthopedic devices, made by specialists in the cities, were elaborate and heavy, and were fitted with big boots that made a child feel out of place in the village. Surely, thought the health workers, there must be more simple, low-cost alternatives.

So, five years ago, the health workers met with the other villagers of Ajoya to ask for community support to start a rural program for disabled children. The villagers responded enthusiastically and PROJIMO began.

Over the next few years, adventurous rehabilitation specialists with a sense of innovation and community commitment—including physical and occupational therapists, brace makers, limb makers, wheelchair makers, and special educators—made short volunteer visits to the program, to help teach their skills to the village health workers. As appropriate methods and skills were tried and developed, they were drafted into a series of simple clear guidelines, experimental instruction sheets and handouts for families. These were tested and corrected over and over again until finally they were put together into a booklet, which slowly grew into a big book (670 pages with over 4000 drawings): Disabled Village Children.

Today, among a wide range of rehabilitation services including physical therapy and correcting club feet, the disabled team makes low-cost, lightweight braces, wheelchairs and artificial limbs at only one-tenth the cost of less appropriate models in the cities. Word of the villager-run program has spread, and disabled children have been brought to Ajoya from 10 states ofMexico. More than half come from the slums in the cities. In a village of 850 people, the PROJIMO team has helped meet the needs of over 1500 disabled persons mostly children and their families. Families of disabled persons are starting sub centers in other towns. And visitors to PROJIMO from different countries and programs arc taking home ideas for forming their own programs run by disabled persons.

To those who have been expecting copies of the book for over a year, we apologize for the long delay. In part the delay has been due to hundreds of excellent suggestions and new ideas that have poured in from all over the world in response to our request for feedback. Typesetting had already begun when in September, 1986, David Werner took a trip to India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and visited 30 community rehabilitation programs. He gathered so many important new ideas that we had to stop the press to add them.

Disabled Village Children differs from other rehabilitation manuals in several important ways:

-

It has been written from the “bottom up”—through the experiences and trials of a user directed village program in a developing country.

-

The information is simplified and clear, but complete. It is not just what experts think village workers should know. Rather it is a collection of methods, ideas and suggestions that community rehabilitation workers, families and disabled persons have found most useful.

-

Above all, the book has been developed for, by and with disabled persons and their families. It focuses on the strengths of disabled persons and builds on these. It encourages the user to take a creative, problem solving approach, to adapt rehabilitation aids and activities to the local situation.

-

Finally, the book has a political bias: empowerment of the disadvantaged. It recognizes that disabled persons especially children in poor communities are often the most marginalized of all. Disabled persons and their families need to join together with all others who are treated unfairly, to work toward a society that is more loving, and more just.

It is essential that community health workers learn more about meeting the needs of the disabled. We hope that Disabled Village Children will help serve this purpose.

Disabled Village Children is organized into 3 parts. Part 1, “Working with the Child and Family: Information on Different Disabilities,” includes descriptions of common disabilities such as polio, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, club feet, birth defects, spinal cord injury, amputations, mental retar- dation, blindness, and deafness.

Excerpts from Part 1 of Disabled Village Children

Part 1 begins with ideas for prevention, mentioning some general causes of disability in children.

The overuse and misuse of medicines in the world today has become a major cause of health problems and disabilities. This is partly because medicines arc so often prescribed or given wrongly… And it is partly because both poor families and poor nations spend a great deal of money on overpriced, unnecessary, or dangerous medicines. The money could be better spent on things that protect their health such as food, vaccinations, better water… Of the 30,000 medicinal products sold in most countries, the World Health Organization says that only about 250 are needed.

In chapters describing a particular disability, specific preventive measures are suggested. For example, in the polio chapter, suggestions are given for the individual. (A child with polio has difficulty walking and may not use her leg muscles as much as an able bodied child. Her leg muscles will gradually shorten and the range of motion of her joints will decrease. The shortened muscles are called contractures.)

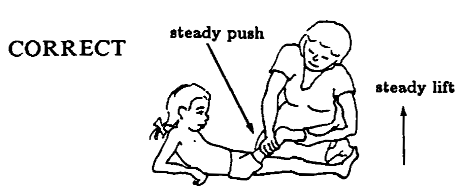

At the first sign of a joint contracture, do stretching exercises 2 or 3 times a day every day.

Stretching exercises work better if you stretch the joint firmly and continuously for a few moments …instead of ‘pumping’ the limb back and forth.

|

CORRECT

|

INCORRECT

|

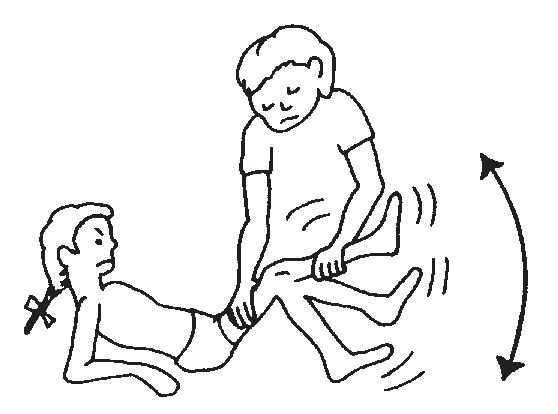

Prevention in the community is also important. (The best protection against polio is a vaccination. But the vaccine needs to be kept cold until used to be effective.)

Seek community help with vaccination and in keeping vaccines cold. Sometimes vaccines do not reach villages because health posts lack refrigeration. but often storekeepers and a few families have refrigerators. Win their interest and cooperation.

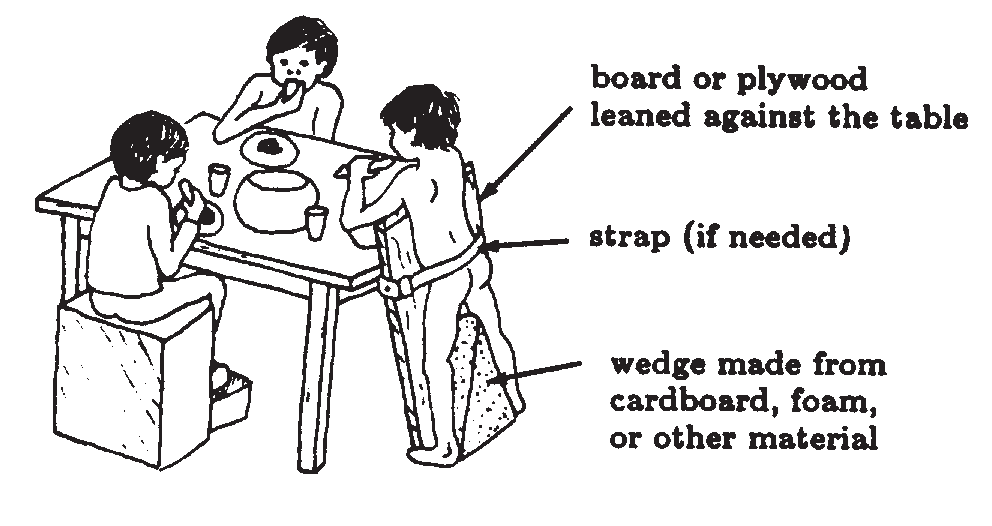

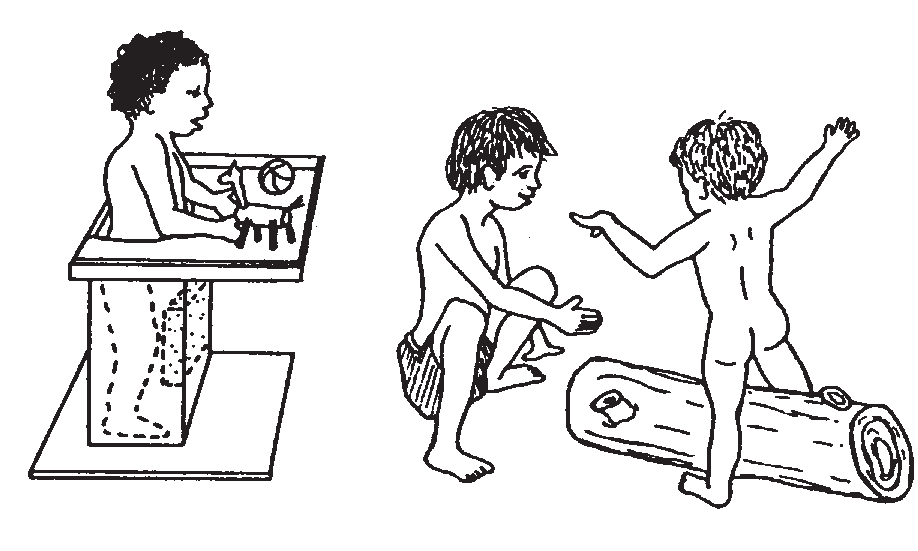

Each chapter that describes a disability also contains ideas for therapy. Here is part of the cerebral palsy chapter:

|

|

|

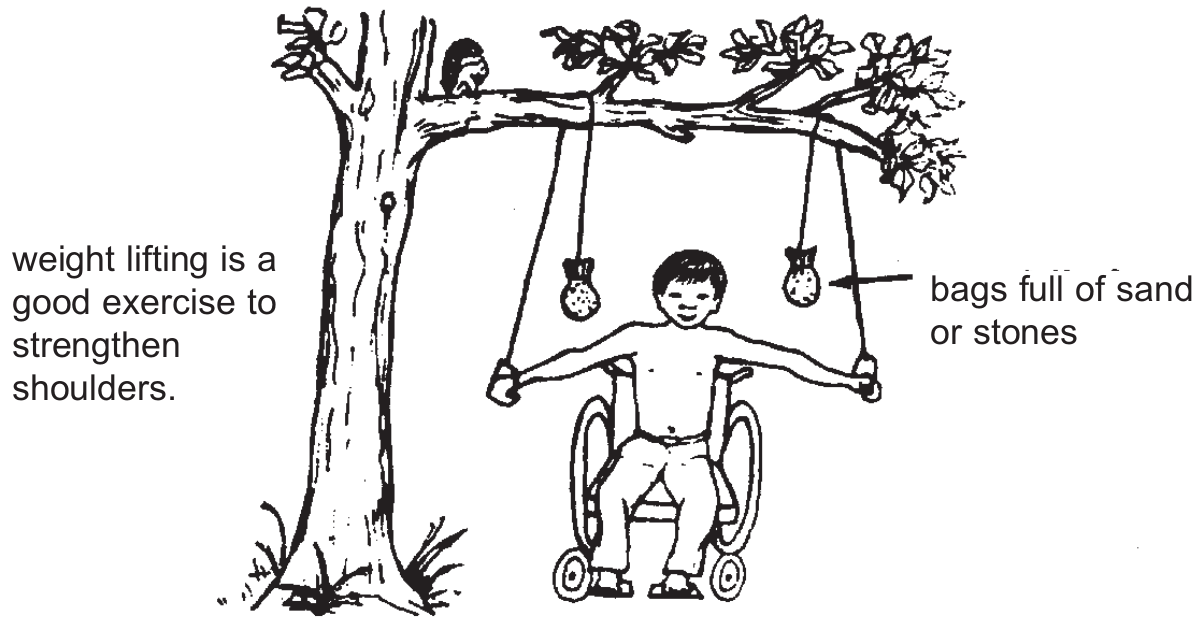

There are therapy ideas for children with spinal cord injury:

Muscle re-education: All muscles that still work need to be as strong as possible to make up for those that arc paralyzed. Most important are muscles around the shoulders, arms, and stomach.

|

|

|

Disabled Village Children emphasizes our need to he aware of local customs. This example is from the deafness chapter:

|

|

|

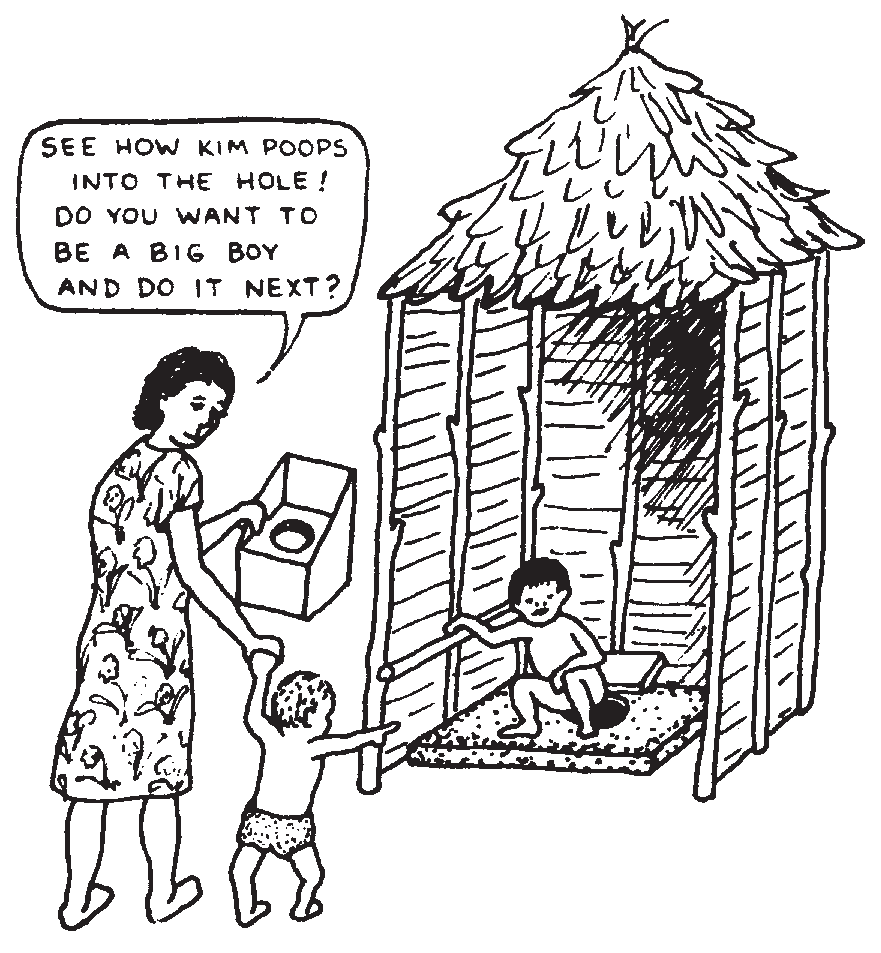

One section of Part 1 is called “Helping Children Develop and Become More Self-Reliant.” It shows aids and ideas to help children learn to…

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excerpts from Part 2 of Disabled Village Children

Part 2 of Disabled Village Children is called. “Working with the Community: Village Involvement in the Social Integration, and Rights of Disabled Children.”

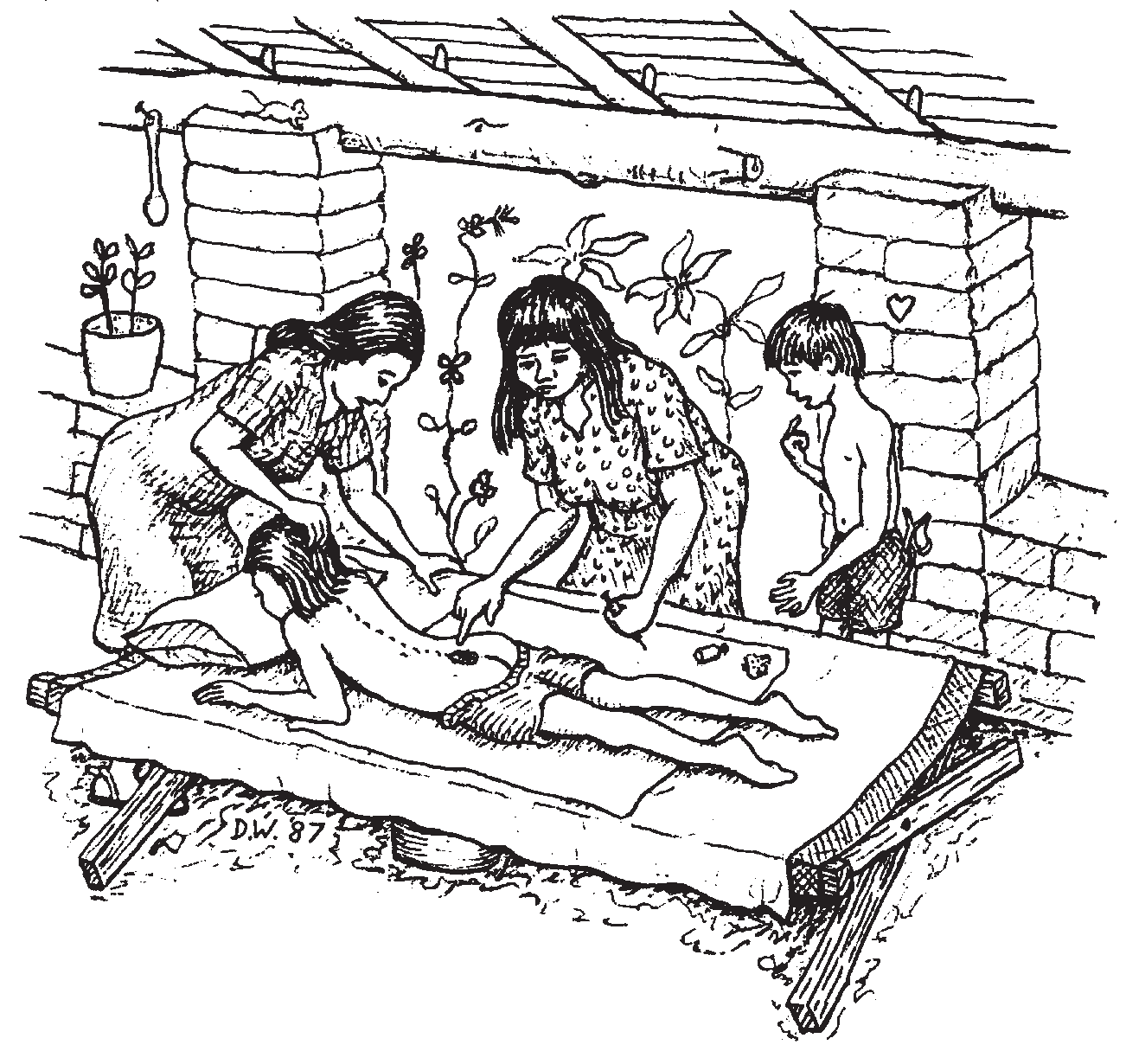

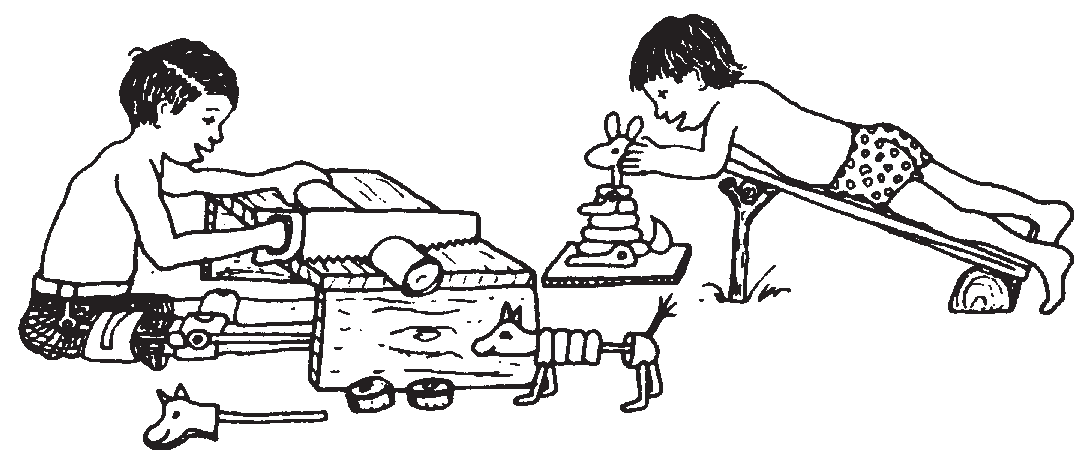

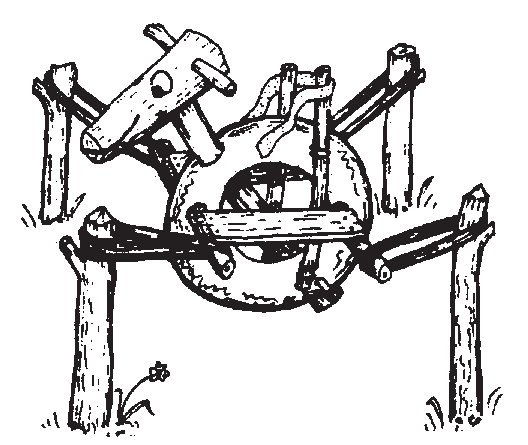

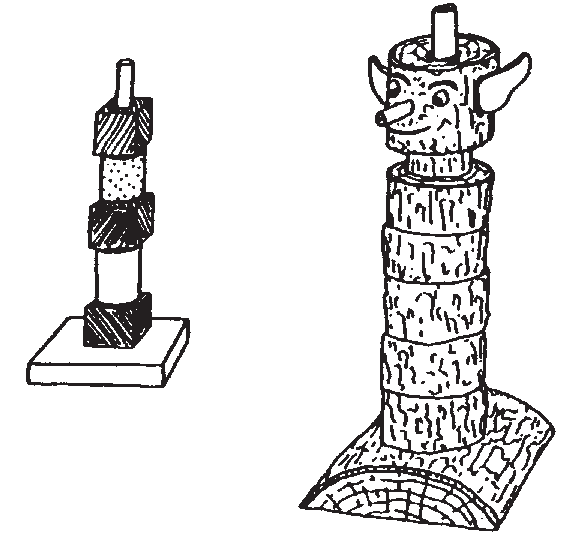

Part 2 shows ways of making fun playground toys with simple materials.It also gives ideas on how to make small toys. It also gives ideas on how to make small toys:

|

|

|

This part also describes ways able bodied children and disabled children can learn from and help each other. It gives advice about organizing a village rehabilitation program and provides examples of community directed programs.

Excerpts from Part 3 of Disabled Village Children

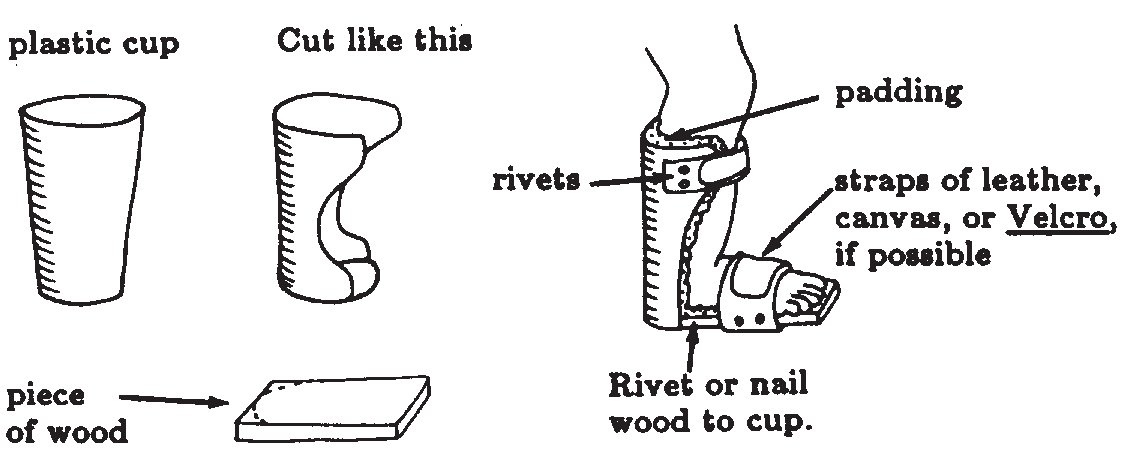

Part 3 is called, “Working in the Shop: Rehabilitation Aids and procedures.” This part of Disabled Village Children explains, among other procedures, how to use casts to correct .joint contractures and club feet. It also describes ways to make casting materials, special seats and many other aids, such as …

…low-cost braces for a small baby…

…splints…

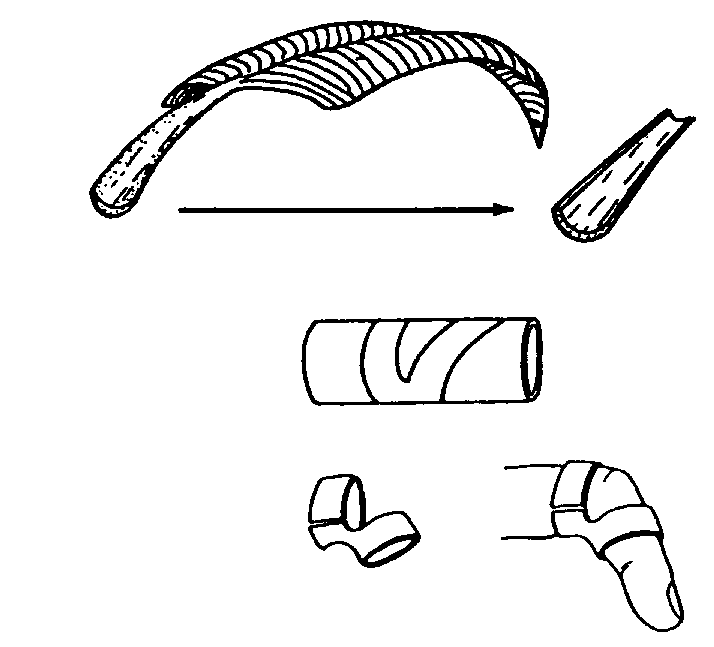

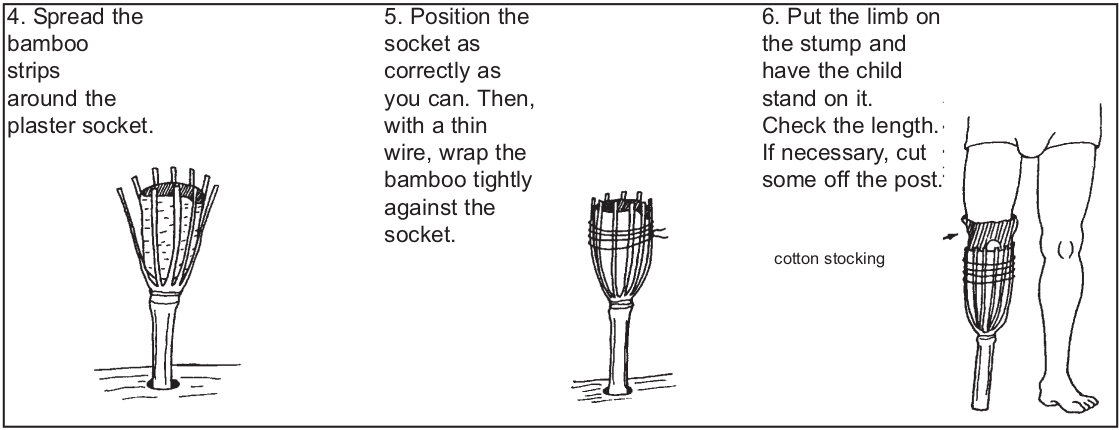

…artificial limbs…

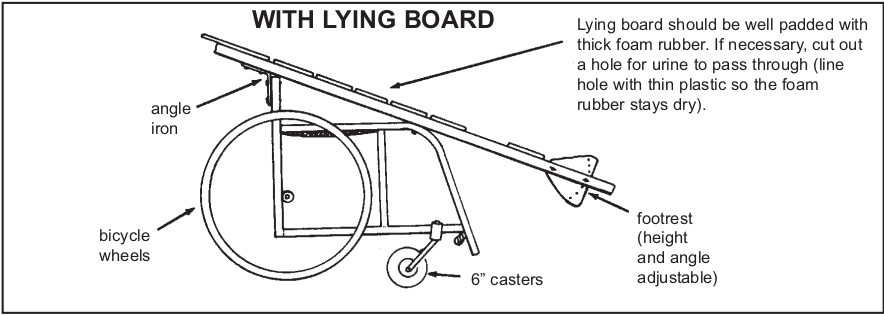

…and wheelchairs.

A People Centered Strategy: Attacking Diarrhea in Mozambique

By invitation of the Ministry of Health, in March 1986, David Werner visited Mozambique to help look for ways to improve its diarrhea control program.

In most poor countries, dehydration from diarrhea is a major cause of death in children. In the early 1980s, following WHO guidelines, Mozambique initiated a diarrhea control program based on oral rehydration therapy (ORT). In the coastal city of Beira, a factory was built to produce oral rehydration solution (ORS) packets for distribution through health centers to mothers of children with diarrhea. (The aluminum foil packets contain sugar and salts for making one liter of ORS). A national campaign to promote ORT was launched.

In spite of a great deal of good will, advice from international experts, and economic investment, the diarrhea control program has largely failed. Even in the city of Beira, where the packets are produced, a recent study showed that nearly one of every four children still dies of diarrhea.

South African Sponsored Terrorism in Mozambique

One reason for the failure of the ORT program is terrorism. Just as the U.S. pays the Contras to destabilize the popular government in Nicaragua, South Africa supports Bandidos to terrorize and try to overthrow the Mozambique government. Sabotage of power lines paralyzes production in the ORS factory. Attacks along highways obstruct distribution. The murder of health workers and burning of village health posts have weakened the health infrastructure. And the economic crisis, famine and chronic malnutrition aggravated by the terrorism increase the death toll from diarrhea. The Minister of Health is trying hard to sec that the people have basic health care. But he comments bitterly that “Our children will never experience their right to health until the apartheid government of South Africa falls.”

Another reason for its failure is that the ORT Program is weak in its education component both for health workers and for families. Partly because of shortages, mothers are usually given only one packet of ORS. And because ORS is promoted as “medicine” (which it is not) mothers expect it to slow down the diarrhea (which it does not) so they feel it doesn’t help, and stop using it.

Complicating the shortage of ORS packets is that they are a source of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), which is used for baking cakes. In Maputo many nurses who have access to ORS packets supplement their income by baking and selling wedding cakes! On the black market, an ORS packet can sell for 700 meticaes (U.S. $0.30 black market value, or U.S. $14.00 legal dollar value). Since the “product approach” to ORT has failed, the Ministry of Health took interest in arguments for an “educational, home-mix approach,” put forth by David Werner in December 1985.

Just as Mozambicans face violent opposition front their South African neighbors, Central Americans are in a similar crisis. And the U.S. is the aggressor. Maintenance of health care in the region is destabilized by U.S. military actions. Lives are being lost. Please join lit the struggle to STOP U.S. INTERVENTION IN CENTRAL AMERICA.

While in Mozambique, David had a chance to visit Inhambane, a coastal town where, in spite of food shortages, the death rate from diarrhea was unexpectedly low. To find out why, he and the District Health Officer met with a group of 40 women from one of the poorest neighborhoods. They found that the women, disappointed with the ORS packets (because “it doesn’t stop the diarrhea”) continued to use their local traditional treatments of diarrhea. Local treatments include giving the children papinha (broth or thin porridge) made with rice, wheat flour, or local tubers. Mothers were using “cereal based” oral rehydration.

Although still not promoted by WHO, studies at the International Centre for Diarrhoea Research in Bangladesh, and independent studies in Nepal and elsewhere, have shown that cereal-based oral rehydration solution (CB ORS) is in many ways more effective than sugar based solutions. Sugar speeds absorption of water from the gut into the body, but a strong solution of sugar also pulls water back into the gut. Therefore sugar solutions do not reduce the diarrhea; they replace the liquid that is being lost. By contrast, cereals are made of large carbohydrate molecules that do not pull water back into the gut. As fast as it breaks down into sugar, the body absorbs it. For this reason cereal based ORS actually slows down diarrhea. Also, because absorption into the gut is not a concern with cereals, a much more concentrated solution can be used.

Therefore, CB ORT can better meet the nutritional needs of the child. Also, measurement is not critical. Thus families can use whatever cereal they have to make a safe, effective home remedy for diarrhea.

Can it be that this group of village mothers in Inhambane has found a better answer to diarrhea control than the WHO experts? And will the Ministry of Health be willing to listen to them? The answer to both questions appears to be “Yes.”

The Ministry of Health is now adopting a revolutionary plan for diarrhea control which includes the following original features:

-

The main focus is on education and self-reliance (rather than on ready made products and increased dependency).

-

Home mix cereal based ORT will be promoted, adapting recommendations to the traditional cereal of each area.

-

School teachers, schoolchildren and women’s organizations will be recruited as the main promoters and educators (rather than only health workers).

-

Participatory research. Teachers, school children and people in communities will be encouraged to experiment with different approaches to education, administration and implementation of diarrhea control, to record traditional home remedies, and to compare results and acceptance of different oral rehydration solutions.

David Werner will return to Mozambique later this year, to help plan the educational component and develop teaching materials for the country’s new diarrhea control strategy.

Project Piaxtla Updates

Village Health Worker Becomes Doctor—And Returns!

When more than 10 years ago, the Hesperian Foundation agreed to help sponsor two of the young village leaders of Project Piaxtla through medical school, everyone knew it was a gamble. Could the vision and commitment of two village health workers, outstanding as they were, survive all those years in the big city? Would the peer pressure, elitist values, and misdirected priorities of medical school corrupt them? Would they still be willing to work for farmer’s wages, and treat their fellow villagers as equals? Would they even return?

Although some members of the Piaxtla team were convinced that the two village health workers would never return, the decision was made to send them to medical school. Medically, the village team felt little need for a doctor. Experience had taught them that a well trained village health worker can often help people overcome common health problems more effectively than the average doctor and with fewer barriers of language, attitude and education. Politically, however, the team had felt an increasing need for a titled doctor, as a strategy for self defense.

Since it began in 1965, the villager-run health program has suffered repeated attacks from the medical establishment. Although it has had suport from the Ministry of Education, and has helped to train health workers for the Ministry of Agrarian Reform, the Ministry of Health has repeatedly tried to close down the program. So have certain private doctors from larger neighbor- ing towns. Medical professionals have opposed the program mainly because the village health team has often assumed the role of “patient advocate,” defending and educating people about the standard abuses of self serving doctors and medical facilities.

Confrontations between the village team and government health services became more extreme when, eight years ago, a government medical post was opened in Ajoya (the base village for Project Piaxtla’s training and referral center). In spite of offers by the village team to cooperate with the government center, its young doctors consistently tried to undermine the villager run program. Tension came to a peak when one young doctor went too far. Not only did he leave his two village “auxiliary nurses” pregnant, he economically ruined family after family by sending patients to a corrupt surgical center in the city for surgery they did not need. During his year of “service” the local incidence of appendicitis tripled. One old man who could not raise the money for an appendectomy was treated by a village health worker with antacids, and recovered. When the village health team began to protest the abuses of the doctor, he threatened to kill them. He then called in a group of health authorities who threatened to close down the village program, “unless it had a doctor who would assume full medical responsibility.”

So the village team began to feel the need for a doctor but for a doctor who was first a village health worker.

Project Piaxtla now has two dedicated young doctors

Both of the health workers who the program sent through medical school finished at the top of their class. And both did return to work with Piaxtla. The first, however, had difficulty reintegrating into the village team. And after a year, he left for the U.S. to live in California.

The second health worker who is also a doctor, Miguel Angel Alvarez, not only reintegrated well into the village team, he brought with him another young doctor, Ana Luisa, his wife. Ana Luisa, like Miguel Angel, is committed to living and working in the village. So, Project Piaxtla now has two dedicated young doctors. Neither likes to make it known that they are doctors. They prefer to be called promotores de salud —health promoters—and share the same responsibility as their village peers.

After Great Difficulties—A New Start

During the first half of the 1980s, Project Piaxtla went through hard times. The introduction of the government health center in Ajoya undermined the people’s commitment to the villager run program, and lowered the morale of the team. At the same time, violence related to increased drug growing in the mountains made travel to visit health workers in outlying villages dangerous. With the economic crisis and devastating inflation, farmers, school children, local officials, healers, and even some of the best health workers turned to growing opium poppies. Little by little the villager run health program in some ways became a shadow of the proud pioneer in primary health care that it had once been.

In some ways, however, the Project continued to evolve. Its main focus shifted from health care to organizing poor farmers. It has helped them to defend their land rights, to start cooperative corn (maize) banks, and to take a united stand against corrupt local authority. As a result, a substantial amount of land has been reclaimed by the poor farmers. Along with other measures this has led to a stronger economic base for the poor. In the long run, this process of empowerment and struggle for justice may serve to improve people’s health more than ‘health services’.

With the return of Miguel Angel, the village team has become determined to rebuild the primary care program. It has already made a good start. In spite of the risks of travel into the mountains, the team has made visits to many villages, reestablishing contact with health workers and recruiting new ones.

Cantina Finally Closed

Another important accomplishment of the Piaxtla team, has been to close the local bar. Five years ago the health workers organized the village women to protest the opening of the bar. As a result, Roberto, Miguel and several other health workers were jailed without charge. Protest by the village women led to the release of the health workers and an order by the State Liquor Authority not to open the bar. But a year later, the bar sud- denly opened. The right palms had been greased and a permit issued. While Governor Toledo Corro (who promoted both public bars and narcotics trade) was in office, there was no way to close the bar in Ajoya. As a result of drinking, there were many beaten wives, hungry children, and at least 12 killings.

After the new governor took office in January 1987, the health team, backed by most of the village, again took up petition to close the bar. With the help of an editor of a major newspaper El Debate (whose disabled daughter has been served by PROJIMO) an open letter to the governor was published, calling for the closure of the bar. Five days later the bar was abruptly closed. Most people in the village (even some of those with a drinking problem) are delighted.

Formation of an Inter-Program Team of Villagers as Trainers

This February, local village instructors from Ajoya, joined by two village level instructors from community based health programs in Honduras and El Salvador conducted a training course for village health workers with a new feature. (The visiting instructors participated through an arrangement with the Regional Committee of Community Health Programs of Central America and Mexico.) Participants will become an international, training team of experienced village health workers who can guide new programs in teaching their new health workers.

News From Hesperian Foundation

Memo goes to New York

In August 1985, after ten years with the Hesperian Foundation, Bill “Memo” Bower left the organization for a faculty position at Columbia University’s Center for Population and Family Health, a division of the School of Public Health. He is continuing to work in the area of community health care at the village level, focusing on communities in Africa.

Bill, co author of Helping Health Workers Learn (1982) has been an important part of the Foundation’s health education team. He remains a board member of the Hesperian Foundation’s board of directors, and continues to participate in Foundation work from his New York address.

WHO Award for Health Education

On September 6, 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) named the Hesperian Foundation the recipient of its first international Award for Health Education in Primary Health Care.

One of 33 nominees, the Hesperian Foundation received the $5,000 award at the 12th World Conference on Health Education held in Dublin, Ireland. Professor Lowell S. Levin of the Yale University School of Public Health who nominated Hesperian for the award, said the Foundation’s work has proven that, “ordinary people can become a major and effective resource in health promotion, disease prevention and treatment of common health problems.”

End Matter

Announcing Disabled Village Children

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |