The Yellow Bulldozer or Some Good Things are Happening in South Africa

As I was preparing to depart from South Africa, a five-year-old boy—Anglo-Indian by birth but generically ‘Black’ by the rules of apartheid, the son of my hosts in Johannesburg—pressed a large, thin, brightly colored booklet into my hands.

“This is a present for you,” he said, “to remember us.”

The booklet, which rests beside me now as I write, is titled The Children of Africa. † Its gentle glowing artwork has all the dreamy surrealism of the Rudolph Steiner School. But its present-day fairy tales are woven with the whetted strands of stark realism: uniquely South African in context, yet universal in terms of human struggle.

† The Children of Africa: 5 Stories by Karen Press. Buchu books, Capetown. 1987.

Still emotionally shaken by my visits to the sprawling squatter settlements that garland the country’s imposing cities, I was moved most by one tale in the book, “The Little Yellow Bulldozer.”

The bulldozer—whose name was GG7928, or ‘Geegee’ for short—was unhappy because, when he went out with all the big bulldozers to knock down tin shacks in the squatter settlements, the people would throw rocks and mud at him. One day a pigeon asked Geegee why he was crying.

“Everybody hates me!” replied Geegee. “I hate being a bulldozer! What will help me?”

“No idea, I’m afraid,” said the pigeon. “But I’ll tell you something my grandmother used to say to me:

People may love you

or people may hate you:

The reason’s not what you are,

it’s what you do!

The next day when all the bulldozers went to knock down more shacks, the little yellow bulldozer hid in some bushes and began to cry. When some children who were running from the other bulldozers stumbled upon Geegee they backed away in terror. But Geegee called out to them, “Don’t run away from me. I won’t hurt you!”

Geegee became friends with the children and after the other bulldozers left, returned with the children to the flattened squatter camp. He helped all the people clean the ground and carry supplies to rebuild their shacks.

When all was done, everyone helped clean and polish the little yellow bulldozer, who was so happy he thought he would burst.

“So this is what it’s like to have friends,” Geegee said to himself. And in this way he discovered that what matters most is not what you are, it’s what you do.

Some would say that the ending of this children’s story is unrealistic. They would argue that to reflect the true situation in South Africa today, the story would have a much less happy ending. Realistically, they say, the next day the squatters’ shacks would have been bulldozed down again; any leaders or protesters would have been beaten and detained. Geegee, the rebellious bulldozer, would have been at best impounded for six years, and at worst dismembered for parts.

But the symbolism and significance of this triumphant fantasy reaches far beyond the day-to-day violence. It reflects the vision of countless people in South Africa—men, women and children; Black, Brown and White; affluent and impoverished; Christian, Jew, Hindu, Moslem, Atheist—who have joined together in the common struggle for a non-racial democratic South Africa.

Indeed, what impressed me most on my visit to South Africa—apart from the absurdity and brutality of institutionalized racism—was the enormous energy, commitment, and solidarity of large numbers of people and groups that have dared to take a stand against apartheid. There is a depth of feeling and understanding among those united in the struggle against apartheid that cuts across racial, religious, and cultural barriers more than in any other country I have visited.

It seems ironic that the most exciting and inspiring aspect of my sojourn in apartheid South Africa was the opportunity to share experiences with so many people committed to working toward a just, completely non-racial society. Many of these courageous people have suffered harassment or even detention for the stand they take. They know only too well detention for the stand they take. They know only too well that a rebellion or protest today will not lead to social transformation tomorrow.

But nearly everyone I spoke to believes that the apartheid system will fall. And it is that faith and determination that will make it happen. Not this year or next, perhaps. But the day of the little yellow bulldozer and of empowerment by the people must and will come.

Pretoria’s Victims in Mozambique

Any doubts I might have had about the brutal injustice of South Africa’s apartheid system were dispelled during my recent visits to Mozambique. Twice in the last three years I have gone to Mozambique by invitation of its Ministry of Health, to help with the community and educational aspects of the primary health care initiative. In trying to meet the people’s basic needs, this small besieged country has faced enormous obstacles. After winning its independence from Portugal, the new “People’s Republic of Mozambique,” led by FRELIMO, was determined to provide equitable health care and primary education to all of its people. In spite of a weak infrastructure and dire poverty, during the first years following liberation, major breakthroughs were made in meeting people’s basic needs. Thousands of village health posts and schools were set up throughout the countryside. Mozambique won widespread praise for its progress toward universal primary health care and education.

However, the South African government was displeased to see the increasing success of a neighboring country that had overthrown White rule. So South Africa’s security forces began to recruit, arm, and finance a rebel faction called RENAMO, a rebel force originally promoted by Ian Smith of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In the first years following independence, the damage caused by RENAMO had been bearable. But with the escalating support from South Africa, along with its training in strategic terrorist destabilization tactics, the rebels began to severely undermine the economy and infrastructure of the Mozambican society.

Parallels between South Africa’s Destabilization Tactics in Southern Africa and US. Intervention in Central America

South Africa’s support of RENAMO in Mozambique (and of UNITA rebel forces in Angola) is remarkably similar to the US government’s support of the Contras in Nicaragua. Parallels include blatant violation of international lava, covert supply of arms and explosive, training in terrorists and the destabilization tactics of ’low-intensity warfare’, denial of military and intelligence involvement by the intervening powers, and shameless lies officially issued to the public. It therefore comes as no surprise that ultra-rightists within the U.S. government, led by Senators Jesse Helms and Robert Dole, have supported both the Contra and RENAMO terrorists as ‘anti- freedom fighters’, and have tried to negotiate $17 million in military and ‘humanitarian’ aid for RENAMO.

Like the Contras in Nicaragua, the RENAMO banditos (as they are known in Mozambique) have killed far more civilians than soldiers, And like the Contras, the banditos have often trade special targets of health posts and schools in the rural areas. In some of the provinces in Mozambique, up to 80% of the health posts and 60% of the primary schools have been destroyed. Attacks are strategically focused to maximize terror and to cripple the economy. Communal farms, agricultural equipment, and storage facilities are routinely attacked. Rather than killing their victims, many are left disfigured or disabled, since invalids place greater economic burden on the country than 40 the dead. This common practice to chop off ears tongues, and hands. Countless persons have been disabled from stepping on land mines: In one town near the border of Malawi, the terrorists reportedly scattered in the streets mini hand grenades in the form of ball point pens; to explode when children picked them up.

During my stay in the coastal town of Inhambane in 1986; a field trip to a neighboring village had to be cancelled, because the time before, terrorists had stopped an automobile on the road and burned a family alive inside it. In 1987, while I was visiting the northern province of Nampula, a band of approximately 3,000 banditos raided a nearby town at the edge of air estuary: The terrified people fled in chaos across the chest-high waters. In the scramble, a group of children drowned. (This was related by a badly shaken Norwegian volunteer who had witnessed the event two days before.)

The Toll in Mozambique

The toll of this youth Africa-sponsored destabilization campaign (’low-intensity warfare’) in Mozambique is hard to estimate. A recent report estimates the total number of unarmed Mozambican civilians killed by banditos is the past

two year is more than 100,000. UNICEF has calculated that between 1980 and 1985, about 230,000 children perished because of the terrorism. Nearly 4 million civilians (abut one-third of the country’s population) have been uprooted. Hundreds of thousands have died from: malnutrition and preventable disease, due to famine, economic, crisis, and breakdown in health services that the relentless assaults have precipitated.

For example, the Ministry of Health, assisted by UNICEF, built a big factory in the coastal city of Beira -to produce packets of ORS (Oral Rehydration Salts) for treatment of diarrhea, one of the biggest killers of children in the country. However, the factory, has been unable to produce more than a fraction of the projected number of packets because the city’s electric supply, which comes from a hydroelectric dam in the mountains, has been repeatedly sabotaged by the banditos. Because of this and even mare because of the increased poverty and poor nutrition produced by the relentless terrorism in Beira itself, a rent study showed that up to 14 children per 100 are still dying from diarrhea.

It was a thrill for me to work in Mozambique, with progressive ministries of health and education that are fully committed to serving the entire population as best they can. But the obstacles caused by RENAMO and the South African government are overpowering: On my first visit to Mozambique, the Minister of Health said to me, “We are doing all we call to improve the situation of our people. But we know that in spite of our most valiant efforts, the hunger of millions of our people, and the tragic, preventable deaths of hundreds of thousands of our children will continue until the apartheid South African government falls.”

The Impact of the South Africa-Supported ‘Law-Intensity War’ (Terrorism) in Mozambique

-

484 health posts and centers destroyed since 1982 (42% of nation’s total) depriving 2 million people from care.

-

2,518 schools (serving 500,000 children) forced to close because of rebel attacks.

-

One-third of Mozambicans face starvation. 10% of Mozambicans are homeless.

-

4 million have been displaced (one-third of population).

-

Annual per capita income has dropped to half that in 1980- now $95 per year (compared to Ethiopia, $110).

-

42% of nation’s budget spent on defense.

-

100,000 (perhaps as many as half a million) unarmed civilians killed by terrorists. Thousands more tortured and disabled.

-

230,000 war-related deaths of children between 1980 and 1985.

International Reactions Against—and in Favor of—South Africa

The torture and atrocities Wrought by RENAMO have unleashed worldwide condemnation. South Africa’s proven, (although repeatedly denied) support of the RENAMO terrorists, along with the well-documented human rights violations and brutality of the apartheid system within South Africa, have been condemned by the U.N. Security Council, the World Court, most nations, and all human rights organizations.

Many countries have mandated sanctions and embargoes against South Africa. Across Europe, the U.S., and Canada, many businesses and international companies have chosen to divest their interests in South Africa. Students in these countries have organized to pressure their university boards of directors to divest. For the sake of appearances, the Reagan administration has occasionally issued rhetorical reprimands and mild sanctions in response to South Africa’s most flagrant human rights abuses.

Yet the U.S. and South African governments still have a lot in common. Above all, both uphold the inalienable right of the strong to exploit the weak. Therefore, in spite of their disapproving rhetoric, the U.S., its allies, and puppets continue to provide economic, moral, and military support to the ‘White Supremacy’ regime of South Africa. Governments that maintain close economic and political ties with South Africa and which have not effectively supported an embargo include the U.S., Canada, Britain, France, Federal Republic of Germany, Israel, Japan, and Chile. It is no surprise that all of these countries (although most proclaim some semblance of democracy) are in fact controlled by, and primarily accountable to the interests of a powerful wealthy private and/or military sector.

The Need for a Selective Approach to the Academic Embargo

When I was invited by NAMDA (The National Medical and Dental Association of South Africa) to visit their country, some of my colleagues in the U.S. insisted that I should not go. They urged me to respect the economic and academic embargo against that apartheid nation, with its horrendous violations of human rights.

I share my friends’ concerns. However, a year ago in New York, I had the opportunity to meet with some of the leaders of NAMDA and of the affiliated Progressive Primary Health Care Network, who gave me some new insights. NAMDA is an interracial assembly of South African doctors and dentists who have united to oppose apartheid and to work toward creating a democratic, non-racial society. NAMDA and other groups courageously struggling for the rights of disadvantaged people under a repressive government, deserve the support from and solidarity with others around the world who are struggling for social justice. Therefore, any economic or academic embargo should be selective, cutting ties with the oppressor, and building ties directly with the oppressed and their defenders. It was with this rationale that I accepted NAMDA’s invitation.

My Visit: The South Africa Tourists Don’t See

My 11-day visit to South Africa was a whirlwind. My hosts from NAMDA and the Progressive Primary Health Care Network wanted me to meet as many people and to see as many projects and activities as possible during my short stay. But above all, I think, they wanted me to experience the ‘real South Africa’ or, as one of the rural health workers who spoke at the NAMDA conference put it, to make sure I saw the country from “a worm’s eye view.”

As a result, my head is still spinning. In the vast array of experiences and impressions that I soaked in during my few days in the country, I do not pretend to understand South Africa. In a way, I feel I understand it less now than when I arrived. Certainly, during my visit I became much more aware of the enormous complexity of the South African situation and of its endless dilemmas and contradictions.

Tourists are routinely shown only one side of South Africa: the idyllic and harmonious facade. I still remember attending, two years ago in New Hampshire, a public lecture by a well-known U.S. travel journalist who presented a slide show on her recent visit to “lovely South Africa.” She had joined a special tour group with official guides who had shown her all the marvels, tranquility, and luxury of those parts of South Africa through which important visitors are selectively chaperoned. She learned from her guides that “reports of racial conflict in South Africa are grossly exaggerated,” and that “the conditions and opportunities for Blacks in South Africa are far better than in neighboring countries.” The manager of the five-star hotel where she stayed offered that if a guest should witness any mistreatment of Blacks by Whites, that he would refund that guest’s hotel bill.

The U.S. journalist had returned from her travels completely convinced that the South African government is doing everything in its power to provide equal opportunities to its Black citizens and to promote health and justice for all the people. Although at the time my knowledge of South Africa was scant, I was amazed at this journalist’s naiveté. Now, after visiting South Africa myself, I am incredulous. One would need to travel with ear plugs and blinders to remain unaware of the crushing socio-racial inequities and brooding unrest which are so forcefully yet tenuously contained by the apartheid system.

I must admit that the exposure I got to South Africa through my progressive hosts was designed to give me exactly the opposite impression as that recorded by the journalist. In 11 days, I traveled to four major cities: Johannesburg, Durban, Capetown, Port Elizabeth. In each I was escorted through an endless array of crowded townships, squatter settlements, and rural ghettoes. Repeatedly, beyond the sea of tin and cardboard shacks widely separated by barren strips of ’no man’s land’ towered the luxurious hotels, modern office suites, and industrial complexes of the presiding Whites. I learned that South Africa is truly two worlds, intermeshed and yet uncompromisingly separate. The first world for the Whites and the third world for the Blacks.

South Africa’s first world is a world of wealth and appearances, distrust and fear. Its third world is one of hardship, poverty, resilience, and brooding anticipation. There is a tension in South Africa which penetrates all life and action, a potential explosiveness which is so constant and pervasive that people have learned to live with it and pretend to relax. Altogether, I found South Africa exciting and exhausting, like walking gingerly through an exquisitely maintained rose garden full of land mines.

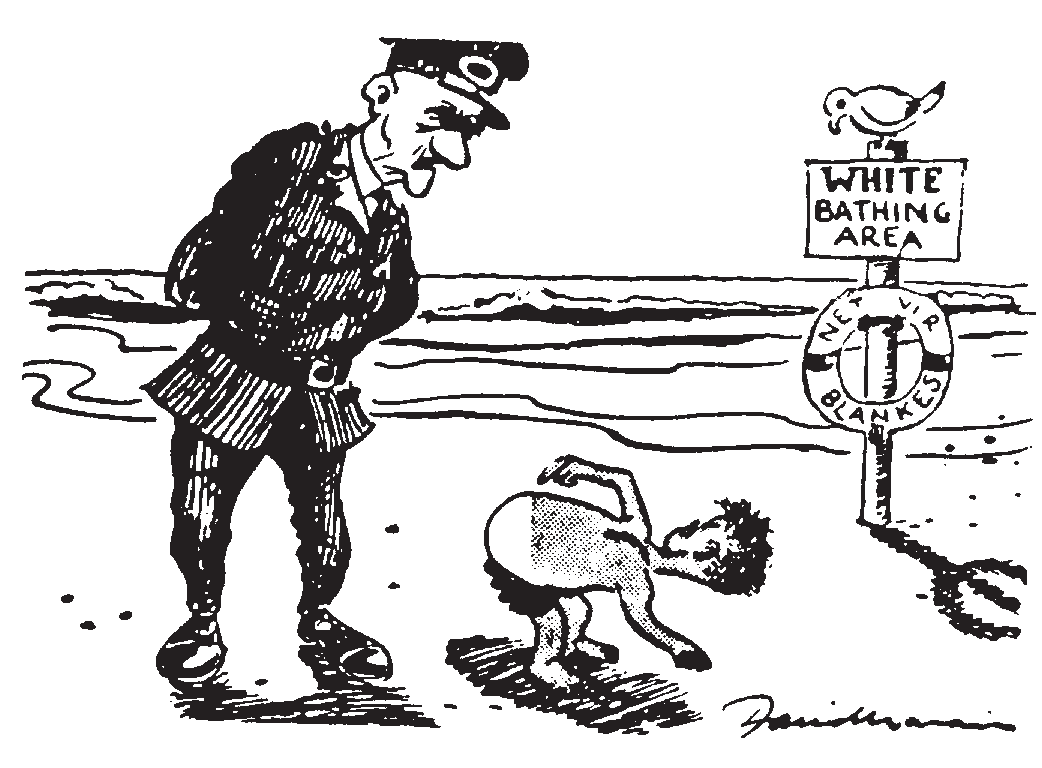

It is hard to say which left a bigger impression on me, the brutality of apartheid or its absurdity. I still find it hard to believe that intelligent human beings can become so fanatical about differences in the color of skin.

According to the legislation of apartheid, South African cities are sharply divided into townships along racial lines. There are strictly segregated residential areas for Whites (Caucasians), for ‘Coloreds’ (persons of mixed White and Black descent), for Black Africans, and for Asians (mostly people originating from the Indian subcontinent). In terms of the relative affluence of the different townships, which is quite visible, there is a clear pecking order with Whites on the top, then Indians, then ‘Coloreds’, and finally Black Africans.

The only official exception to the rigid residency restrictions has been made for Japanese. Because these recently arrived ‘Yellow’ Asians are relatively wealthy and represent foreign industry and investment, the Japanese are considered ‘honorary Whites’ and are welcome to reside and circulate in White townships and hotels. (It is said that the current losses to the South African economy caused from divestment by U.S. and European business have been offset by increasing investments from Japan.)

In spite of the rigidity of the apartheid system, reinforced by the ‘state of emergency’ declared in 1986, sizable cracks are beginning to develop in the high wall of racial segregation. In the last few years there has been an outbreak of ‘grey’ districts (‘grey’ meaning a mix of White and Black). One of these grey districts is D——. It was here that I stayed at the home of Betsy and Rafik, my hosts when I first arrived in South Africa. (Betsy and Rafik are not their real names. I use pseudonyms to try to avoid getting them into any difficulties should there be any official repercussions from my visit or my writings. Citizens are often harassed, or worse, if their criticisms of their country reach the press.)

Betsy and Rafik are both doctors and members of NAMDA. They work in a community clinic in one of the poor Black townships that has a large squatter settlement. Because Betsy is British and Rafik a South African of Indian descent, they have had their share of confrontations with the South African apartheid system. The two met in England several years ago when Rafik was studying medicine there. When his studies were finished the couple moved to Zimbabwe and then to South Africa.

Betsy still remembers her consternation when she and Rafik arrived at the Johannesburg train station. In order to leave the station, they found that the “White’s Only” exit was an overpass above the tracks. For Blacks, the exit was a dark tunnel under the tracks. When at last they were out of the station, they found that only first class cabs were available. These give rides only to Whites. After a long wait for a second class cab (which takes Blacks), they finally gave up and set out on foot carrying all their luggage.

Trying to find a place to live presented a major difficulty. Rafik and Betsy could not tell anyone they were married because at that time mixed marriages were illegal. Subsequently the law has been relaxed and interracial marriage is permitted. In terms of status, residence, and rights, the White partner is considered Black.

D——- is officially a White neighborhood, yet Black families have succeeded in settling there in increasing numbers. Strictly speaking this is against the law, but it has been possible because both real estate agents and government officials have found the illegal ‘graying’ of the neighborhood highly profitable. As more and more conservative Whites move out, homes are put up for lease to middle class ‘Blacks’ at outrageously high rates. Non-Whites are allowed to move in and stay there only if they make periodic payoffs to the ‘Residency Police’.

One day when Betsy came home from work, she found a note on her door from the ‘Residency Police’ captain, ordering her to report and leaving a phone number. When she called him, he told her that since her husband is Indian, it was illegal for them to live in D——-. He paused and then said, “I understand you’re a doctor.”

“Yes,” said Betsy.

“Do you have any medicine for asthma?” asked the captain. Betsy said she did.

“Well,” said the captain, “I suffer from asthma. Can you bring me the medicine tomorrow?” Somewhat confused Betsy arrived at the captain’s office the following day. In a brown paper bag she carried a bottle of asthma medicine. When she was alone in the office with the captain, he asked her, “Did you bring the medicine?”

“Yes,” said Betsy and handed him the bag. When the captain reached in and took out the medicine, he turned pale, shook his head, and sent Betsy on her way. It wasn’t until afterwards that she realized her own naiveté. What the captain had expected was a fat roll of Rands in exchange for not evicting Betsy’s family from the graying neighborhood.

Betsy and Rafik’s problems were just beginning. The agent who had leased them the house had assured them that their neighbors were quite liberal regarding questions of race and that there would be no difficulty. They were soon to discover, however, that their next door neighbor was an archconservative and racist. Following the principle that, “Good fences make good neighbors,” behind the high wooden fence that already separated the house, the neighbor put up a three-meter high, sheet metal barricade. Behind that, heavy wrought iron grids covered all the windows on the outside. And on the inside the windows were screened by full length, tightly woven curtains.

One morning, as Rafik backed out of his driveway into the street, his car tire passed over the edge of his neighbor’s curbside strip of lawn. The neighbor dashed out of his house cursing. That afternoon, when Rafik returned, a row of huge cement pilings had been implanted from the edge of the street to the high wall dividing the properties. Two of the pilings were in the middle of the sidewalk. This obstruction of a public walkway is surely unlawful. But since the very residency of Rafik’s family is illegal, what can he say?

In South Africa, Blacks outnumber Whites six to one. Yet Blacks, the indigenous inhabitants of the region, do not fully qualify as citizens in their own land. They are not permitted to vote. And until recently they were not allowed to travel or reside outside the huge ‘homelands’ without carrying special passes.

The land in the parts of South Africa which has been designated as ‘homelands’ tends to be the most arid, desolate, and unproductive of the country (similar to the ‘reservations’ for Native Americans and the ‘stations’ for aboriginals in Australia). A substantial portion of the Blacks in the homelands, therefore, have to spend large blocks of time outside the homelands, working for White bosses on farms, in mines or in industry. Typically it is the men who leave their wives and children behind in the homelands to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Some return occasionally with money. Many never return.

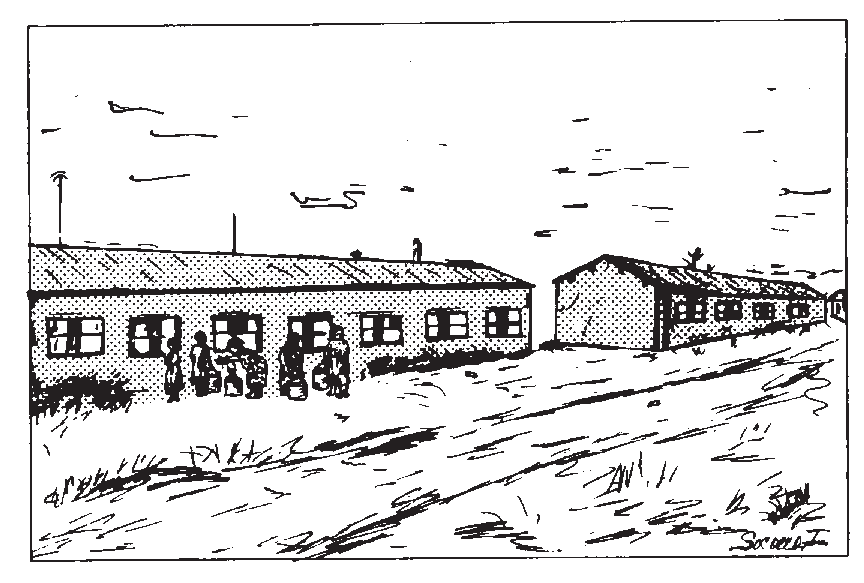

Most of the men who work in mines and industry in the city are required to stay in huge, bleak, crowded, all-male dormitories called ‘hostels’. These hostels, which look like long grey rows of oversized rabbit hutches, are one of the characteristic eyesores on the South African landscape. They represent the epitome of apartheid, where not only the races but also the sexes are arbitrarily kept separate.

In the cities, apart from the men who live in the male hostels, are the hundreds of thousands of women who work as domestic servants for the Whites, and who live in small cramped huts behind their masters’ residences.

However, most of the urban dwelling Blacks live in the Black townships. Because Blacks traditionally have not been allowed to own property, much of the housing in these townships has been built by the government. Mostly it consists of row upon row of ’ticky tack’, low-income flats, where typically one or more families (up to 20 persons) are crowded into one or two small rooms.

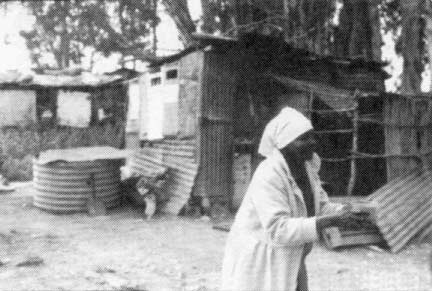

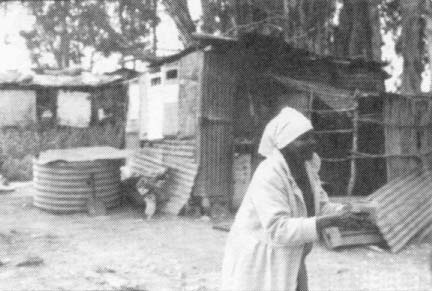

Squatter Settlements—the Seedbeds for a new South Africa

Housing, however, is scarce. An increasing number of people who pour into the cities from the rural areas and homelands end up in the mushrooming squatter settlements. These squatter settlements appear to pose a special threat to the state authorities. This is not only because they arise through independent popular action in violation of the law. It is also because people in the squatter settlements tend to join together and stand up for their rights more than do people in the townships and rural areas. Perhaps this is because the severity of their hardships, the insecurity of their living situation, and their ceaseless struggle for survival leaves them little option but to unite in self-defense. And maybe also in part because, unlike most of the low-cost homes and hostels in the townships and rural areas, the tiny improvised, tin and cardboard shacks in the squatter settlements belong to the people. They are made by their own hands and display their own personal touch. In spite of the extremes of poverty, disease, and suffering, in the squatter settlements I repeatedly got the sense of tough homespun dignity—an invincible autonomy less evident in the track houses of the townships.

Typically, in the squatter settlements, the people organize and select their own community leaders. I had a chance to meet with several of these leaders in some of the squatter settlements in Johannesburg. Some were women and some were men. All I met not only commanded a unique respect from the people, but were clearly their comrades and friends. †

† In some of the older, giant squatter settlements, especially in the Capetown area, local popular leadership is reported to have become corrupt or to have ‘sold out’ to government interests. Some of these corrupted leaders have become very wealthy through demanding ‘rent’ or ‘protection fees’ from the squatters.

In one of the squatter settlements I visited on the edge of Johannesburg, about 12,000 people lived crowded together on an acre of land. This particular settlement had occupied its present site for only a few months. The families had already been evicted from two earlier sites in other parts of the city. When their shacks on the first site were bulldozed down, the government had given them permission to move onto the second site. But soon the second site was also bulldozed. The people moved once again. The third and latest site was next to a coal depot. When we visited, people told us that the authorities had announced that within two days, the seven or eight hundred houses on one side of the wide dirt roadway would again be bulldozed down. The people had been given one week’s warning to remove their shacks. But they had no place to go.

I was enormously impressed by a young Black man called Ritter (a pseudonym) one of the main organizers of the squatter camp. Because such organizers are at particular risk of muggings and detention by the police, Ritter (who is single) does not even have his own shack to live in. Every night he sleeps with a different family and keeps on the move, so that when the police raid they have less chance of finding him.

Ritter explained that water is a major problem in Site 3. The Red Cross has supplied a number of large water storage tanks and the military had promised to regularly bring in tank trucks to fill them. “… Part of their good will campaign,” explained Ritter with a wry smile, “to win the minds and the hearts of the people.” However, after a few weeks, the military stopped supplying water. So now, the women walk half a mile down the road to get their water from inside a huge all-male hostel. Several women have been raped going for water. Sometimes they are then thrown inside huge metal dumpsters outside the hostel.

Ritter explained that at night, groups of men (apparently from the men’s hostel) routinely come into the squatter settlement to steal, vandalize, and rape. There were five killings in the first two months. Consequently, Ritter and some of the other leaders in the settlement called a meeting, and the community selected a discipline patrol of men to function as night watchmen. However, after a few confrontations with the outside thugs, one night the police arrived in force, assaulted the community’s night watchmen and hauled them away in their vans. “We still don’t know what became of them,” said Ritter. “We hope they’re in jail.”

“But why,” I asked, “would the police want to stop the people from taking action to protect themselves against thugs and murderers?”

Ritter looked at me benevolently, “You’re new in South Africa, aren’t you?” he said. “It’s a standard part of the government’s strategy, that’s why. The thugs that come in the night to terrorize us not only have police protection, they are put up to it by the police.”

It is a basic tactic of oppression: divide and conquer. All over the country and especially in squatter settlements, the State authorities organize and incite one group of Blacks to rise up against another. They try to keep the indigenous ’tribes’ separate and traditional disagreements inflamed so that they can say to the world, “See how these primitive people keep fighting each other. It is our job to enforce peace and discipline.”

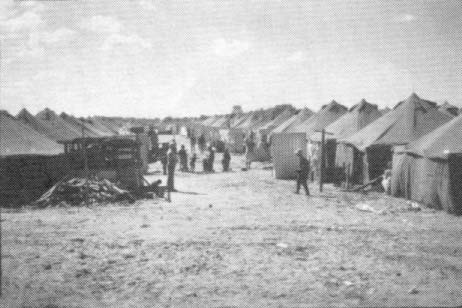

Improved Housing Leaves the Poorest Homeless

Throughout the country some of the oldest squatter settlements, and also the poorest dwellings in some of the townships are being bulldozed down to make way for improved housing. However, the shortage of living quarters is so great that middle class families move in and occupy the improved housing as soon as it is built. The displaced squatters and poor families are often left with no homes and no place to go. To some of these families the Red Cross, various church organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have provided provisional tents. ‘Tent cities’ now spread out along the edges of bulldozed settlements and housing projects.

The living conditions in many squatter settlements are deplorable. Although the South African Council of Churches and other groups have made an attempt to provide water and latrines in many settlements, sometimes there is only one latrine for 80 families. As a result, people defecate between houses, in the fields, on garbage heaps, and even in the streets.

Unemployment in the squatter settlements is up to 60%. Levels of malnutrition are high, especially among children. People in one settlement we visited told us that a recent survey there showed that over one-third of the children under five were seriously malnourished. With the crowding, poor sanitation, and high levels of malnutrition, infectious diseases such as diarrhea, scabies, and tuberculosis run rampant.

There are almost no government health facilities in or near the squatter settlements. Clinics and hospitals are often many miles away. Public transportation to and from many of the settlements is virtually non-existent.

‘Deplorable’ Conditions in Black Hospitals

Even when people from the squatter settlements can get to the hospitals for Blacks, there is no guarantee of good treatment. Facilities are so understaffed that they seem more like stockyards than hospitals. On a ‘quiet’ day a doctor typically sees a minimum of 65 patients. On a busy day he or she may see 125 or more patients.

The waiting hordes move from the huge jostling crowd outside, to one packed waiting room after another. The average wait in line for consultation is about five hours. Around noon, the outside doors to the waiting rooms are closed and those who are still waiting outside to get in are turned away until the next day.

In a poor township of Durban, I talked with a pediatrician in one children’s ‘day hospital’ (out-patient clinic). He admitted to me that although they have ’triage’ nurses who try to spot and give preferential care to severely ill patients, on several occasions babies with diarrhea have died of dehydration while waiting in line for consultation.

Conditions are so bad in many of the Black hospitals that some of the medical profession have begun to protest. In September 1987, a group of over 100 doctors at the government run Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto (a huge Black township in southwestern Johannesburg) published a letter in SAMJ (medical journal of the Medical Association of South Africa) protesting the conditions of Baragwanath Hospital as being “disgusting” and “deplorable.” The doctors went on to write:

The state of affairs is inhumane. Facilities are completely inadequate. Many patients have no beds and sleep on the floor at night and sit in chairs during the day. The overcrowding is horrendous. Ablution [toilet] facilities are far short of accepted health requirements and ethical standards are compromised. Pleas for help have been met by indifference and callous disregard. Patients and their problems are treated with utter contempt by the authorities. Nothing is done to correct this affront to human dignity. Here is human suffering which cannot be portrayed by mere statistics. As the overcrowding worsens we are of necessity forced to lower our expectations in the quality of care we can offer our patients. The uncaring, uncompromising attitude to the handling of sick human beings is beyond belief.

We are making this appeal through the SAMJ in the hope that it may provoke enough response from the profession, at least on humanitarian grounds, to bring about urgent relief to an appalling situation that is rapidly approaching a major crisis.

In response to this letter, the hospital authorities threatened to suspend the employment of all 101 doctors who had signed the protest letter and offered to keep only those who would publish a public statement revoking and apologizing for their accusations. With their jobs on the line, most of the doctors signed a public apology. Some, however, have stood their ground and have taken their dismissal to court. It is still too early to know what the outcome of all this will be. In the meantime, conditions in the Baragwanath Hospital, and dozens like it throughout the country, have not significantly improved.

Another upsetting part about Baragwanath and other Black hospitals in the country is their stark contrast to the hospitals for Whites. Facilities for Whites rank with the best in the world. In Capetown, for example, not far from the hospital where Dr. Barnard successfully completed the world’s first heart transplant, another new huge central hospital has recently been built. It is very underutilized and may remain so even after the apartheid system collapses, for it is designed to provide high-cost, sophisticated tertiary care to the elite. Likewise, in Johannesburg and many other cities of South Africa, new hospital facilities continue to be built to serve mainly Whites, though only a fraction of the beds in many of these newer hospitals are occupied.

Community-based Health care

In response to the deplorable state of institutional health services for Blacks in South Africa, there has been a growing movement for community-based primary health care. Small neighborhood clinics, health posts, nutrition centers, rehabilitation centers, and self-help workshops have been springing up in the poorest townships, squatter settlements, and rural areas. Many NAMDA doctors are involved in these community initiatives, as are a number of progressive health worker organizations and associations. These organizations have been trying to link together the many community-based health programs in the country into a Progressive Primary Health Care Network.

Fascinating to me is the remarkable similarity of approach, methodology, and sociopolitical base between these South African community health programs and many of the grassroots community health initiatives in developing countries, especially where people are struggling for their rights under oppressive governments. Among grassroots organizers there tends to be a growing awareness of the empowering potential of bringing people together to cope collectively with their common health needs. Although many of the programs have been started by progressive professionals or groups of university students, community involvement and leadership has been encouraged. Many of the programs now have their own community health workers, nutrition workers, and organizers. These people-centered health initiatives are becoming important spring boards in the process of community mobilization for healthier social structures.

Virtually all the community-based programs we visited were using Where There Is No Doctor and other Hesperian publications as workbooks. Activists were very familiar with our writings on the politics of health (for example, “The Village Health Worker: Lackey or Liberator?”) and drew on our material in planning their methodology.

The Crossroads Squatter Settlement

Capetown, renowned as one of the world’s most beautiful cities, is nestled on the southern tip of Africa between austerely sculptured mountains and the clasped hands of two oceans. Its ragged coastline outside the city is dotted with the luxurious summer homes and weekend paradises of affluent Whites.

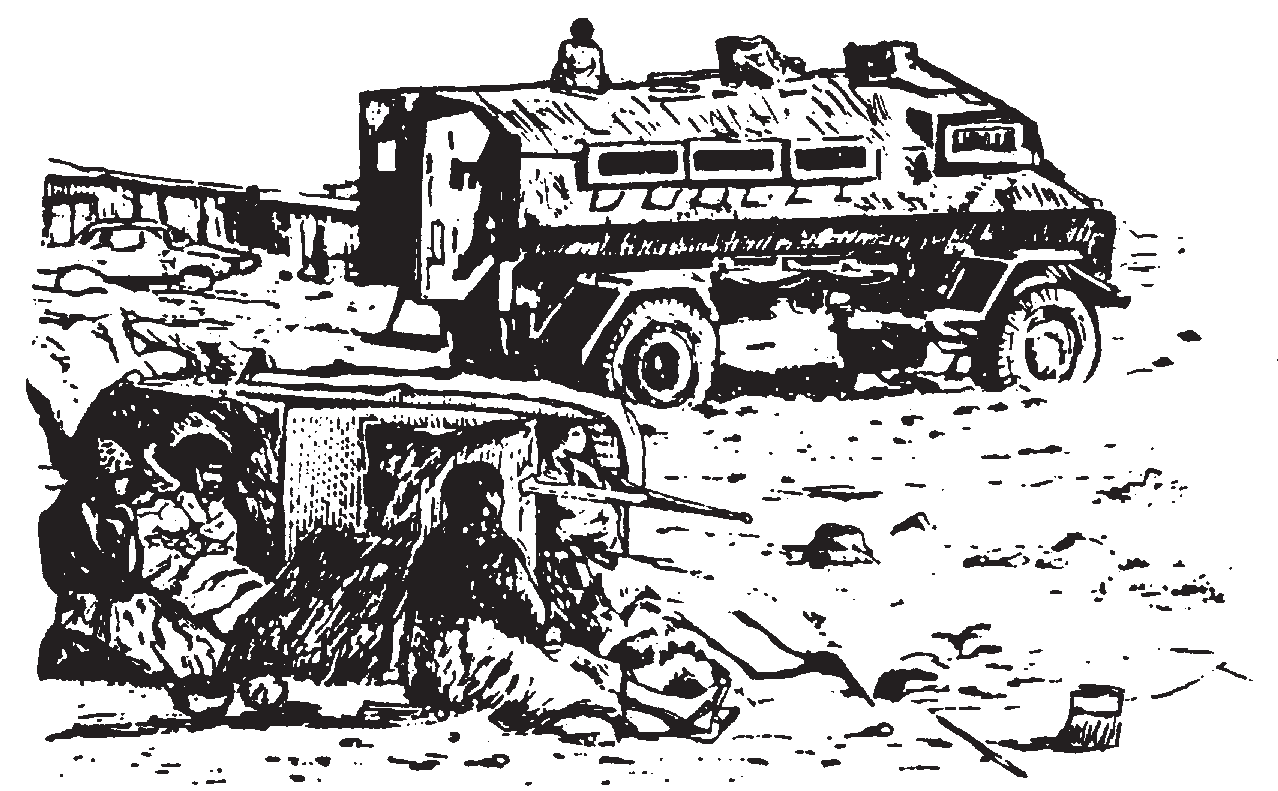

By contrast, the Crossroads sector on a low barren plain outside Capetown is one of the biggest squatter settlements in South Africa. In 1983, when it had grown to a community of more than 120,000, the government decided to destroy the entire settlement. Bulldozers moved in, accompanied by soldiers, police troops, and ‘casspirs’ (huge armored tank-like vehicles designed for riot control).

In some areas the ousted squatters protested or fought back; there were many deaths, injuries, and detentions. In one sector of the settlement, the women bravely stood ground before their huts, against the bulldozers, casspirs, and riot police with their tear gas and rubber bullets. In some parts of Crossroads, the people succeeded in preventing some huts from being bulldozed down. In other parts, the shacks sprang up as quickly as they were leveled.

Several years ago, old Crossroads had become the home of one of the most successful and famous community-based health programs in South Africa. Started by a young progressive doctor, Ivan Toms, the health center soon became a rallying point for a wide range of collaborative health and development activities. †

† Dr. Ivan Toms is now serving a two-year prison sentence. He was charged with refusal to take part in a one-month ‘refresher’ service in the military. He is permitted only one visit and one letter per month.

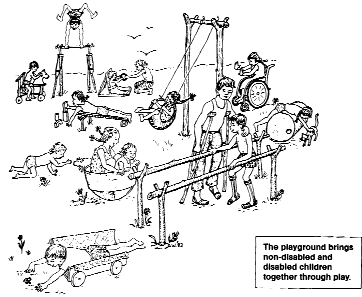

In 1986, during a subsequent demolition raid by the state, the Crossroads community health center was taken over by the military. At that point a decision was made to move the center to the new huge squatter settlement called Khayelitsha where many of the inhabitants of old Crossroads have been forced to move. The program now consists of a network of health and development activities with community health workers, several Philani (nutrition centers), and a small rehabilitation center/day-care facility for disabled children.

In Khayelitsha I had a chance to meet with a group of a dozen community health workers and was very impressed by their energy and skills. To demonstrate some of their teaching methods, the health workers and family members put on a short skit which was as hilarious as it was educational. They also sang a number of songs designed to convey important health messages among them how to prepare a special drink (oral rehydration) for children with diarrhea. The animated pantomime which went with the song made the instructions so clear that I could understand them well, even though they were sung in Xhosa. (I have listened to community groups in several countries of southern Africa and am repeatedly overwhelmed by the richness and beauty of the people’s singing, with spontaneous harmonizing that would put to shame the best barbershop quartets.)

In the community health programs I visited in Crossroads (and throughout South Africa), the ever-present underlying theme weaving through all the discussions, songs, teaching methods, and working policies was a deep commitment to equality and social justice. It seemed that everyone working at the community level is deeply aware that health for the majority will only be possible with an end to the apartheid system. The struggle for health in South Africa, they insist, is a struggle for freedom and equity.

The Community Rehabilitation Center

The extent of involvement and leadership by community people became clear to me when I visited a small day care center and rehabilitation workshop next to one of the Philani nutrition centers in Khayelitsha. The workshop is guided by a young, very humble, extraordinarily capable physiotherapist, Marion Loveday, together with a local assistant, Nomazizi Stuunnan. Many of the mothers who come every day to the center with their disabled children have learned to help their children with needed exercises, activities, and play. Recently, when Marion was having a baby and Nomazizi was not available, the mothers kept the center open and coordinated the physiotherapy and activities for the disabled children.

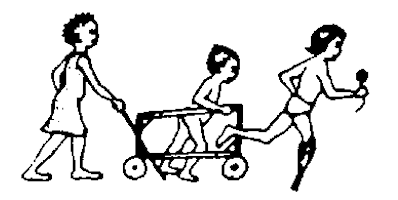

I was greatly impressed by the imagination, innovation, and creative response to individual children’s needs I saw in this modest rehabilitation workshop. People had created a wide variety of simple technical aids using local, low-cost materials. These included therapeutic rolls made by fastening old paint tins together and covering them with sponge rubber; orthopedic braces for a child with spina bifida made by binding plaster of Paris splints to his legs; a special seat for a child with cerebral palsy made entirely of layers of thick cardboard glued together; and a wagon with wooden wheels covered with strips of old car tire, in which a mother pulled both her teenage disabled son and baby from her home to the center.

I left feeling that more was happening in the areas of both rehabilitation and empowerment in this tiny shantytown rehab workshop than I have seen in some of the multi-million dollar rehabilitation centers in other countries.

The Rural Area: the Next Thing to Slavery

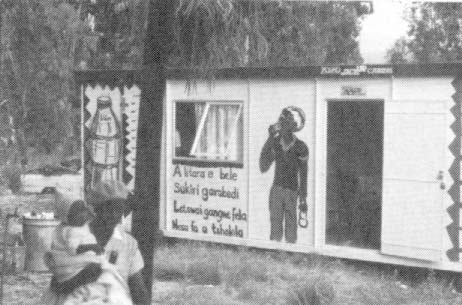

Due to the brevity of my stay in South Africa, I had very limited opportunity to visit community health programs in the rural area. One program I did visit was in Muldersdrift, attending outside Johannesburg. It is run on a volunteer basis by a multi-racial group of university students and instructors who drive out to a number of primary care clinics and provide basic services on weekends.

The small clinic I visited in Muldersdrift, located on a vast empty field on a private farm, was as bright and motley as the students themselves. The walls of the few shacks that formed the improvised clinic were colorfully painted with murals depicting basic health messages. On one wall was a larger-than-life drawing of how to prepare a home mix special drink for treating diarrhea.

Although this rural program struck me as well-organized and important, it was fraught with situational difficulties. The biggest underlying problem was the almost slave-like oppression to which the Blacks in the rural area are subject. As a result of the ‘Big Brother-like’ presence of the White landlords, the student health workers are fearful of trying to organize the people or even of discussing with them the root causes of poor health. They fear that they will be thrown off the land by the owners who permit them to set up clinics on their property, but who keep a watchful eye out for any activities touching on popular organization or basic human rights.

Except in the homelands, Blacks are not allowed to own property. Therefore all the farm land of South Africa proper is owned by Whites. Most of the farms in the Muldersdrift area are relatively small, so that each landholder has working for him 5 to 30 Black families. Typically the families live in long narrow hostels about as wide and high as a line of railway cars. In spite of much open and unused land, the living quarters are even more cramped than in the city slums. Some of the quarters I visited were so small that one bed inside a single room took up two-thirds of the floor space. For six or more members of a family to sleep in the room on a rainy night they would have to cram together on, beside, and under the bed. Because neither the housing nor the land belonged to its inhabitants, the people could not add to their living space. Nor were most of them allowed to plant vegetable gardens on the unused land.

In the cities, mine workers and laborers have now succeeded in forming unions and demanding at least minimum wage and a few basic rights (although the government is now taking action to limit the power of unions and to make strikes illegal). However, still very little has been done to organize farm workers. The few attempts have been violently opposed. As a result, farm workers have virtually no rights. There is no minimum wage and many workers receive nothing but their meager housing and an inadequate ration of food. Generations of families live and die on the same farm without ever leaving except for the men who go to the cities in search of work in mines or industry.

Many of the rural hostels have no nearby water supply nor bathroom facilities. People often have to walk a long way for water. Even though these people are producing most of the country’s food, malnutrition and diseases of deficiency are common, especially among the children. It is reported that four to five Black children die each hour due to malnutrition.

In spite of the good work of the University volunteers, I came away from Muldersdrift with a sense of despair.

Provision of health services in the rural area poses an enormous problem, in part because of the lack of public transportation. Rural weekend clinics have had to establish pick-up points where people from several neighboring farms assemble at a road junction on specified days, where the program van picks them up and takes them to the clinic. After their health needs are attended, the people are transported back again.

Rural South Africa strikes me as very different from rural areas in other parts of the world I have visited. In spite of the good work of the University volunteers, I came away from Muldersdrift with a sense of despair. In Latin America I have chosen to live and work with people in the rural areas partly because their needs are great. But it is also partly because rural people have a kind of rugged independence and self-reliance, in spite of the inequitable land structures. In many ways the rural poor in Latin America are abused and exploited. But still they have a degree of space and freedom. Often there is political latitude (at least clandestinely) to get people together to talk our their problems, to analyze underlying causes, and to take some kind of action, limited as it may be. My impression has always been that in rural areas, people are somehow freer, and that it is easier to get a community program going there than in urban slums.

But in South Africa, I came away with the opposite impression. It is hard to imagine that in South Africa revolution and mobilization of the people will take root in the rural area and then spread to the cities, as happened in China and other countries. It seems far more likely that mobilization for social change will rather take root in urban settlements and townships.

The Class Struggle Behind the Race Struggle

Although I was enormously impressed by NAMDA as a whole, and by both the social consciousness and political courage of many of its members, I also became aware of the wide diversity and inherent contradictions within the organization. NAMDA is committed in its stand against apartheid and to the struggle for a non-racial, democratic South Africa. As a part of this process, it is also committed to working closely with health and development workers at all levels, and to the training and mobilization of community health workers and social activists. It has played a key role in the formation of the Progressive Primary Health Care Network.

Nevertheless, NAMDA’s membership is exclusive; it permits into its ranks only doctors and dentists. Nurses, therapists, and other health workers are allowed to become associate members, but are not given the right to full membership or to vote. Persons in the Health Workers’ Organizations of South Africa have objected to this exclusionary policy of NAMDA, not only as “elitist,” but as “the professional equivalent of apartheid.”

Within the ranks of NAMDA itself, there is an ongoing and heated debate as to whether NAMDA should open its membership to other health workers. Some say yes, some no. Many feel idealistically that the organization should include all levels of health workers, but that strategically the prestige of an all-doctor organization is needed for its political survival. NAMDA’s survival is at best tenuous given its outspoken anti-apartheid stand. (Recently, during South Africa’s latest state of emergency, a large number of human rights groups, alternative newspapers, and religious groups have been officially banned. NAMDA knows that on any day the same fate may befall its own existence.)

Perhaps the best argument I have heard against NAMDA opening up its doors to all categories of health workers is the recognition, by some of the doctors themselves, that doctors too often have an insatiable need to dominate. A merger between NAMDA and the health workers’ organizations could introduce a very real danger of the doctors taking over.

Whatever the final decision, I was impressed that there is a good deal of healthy soul-searching, self-criticism, and internal debate among the NAMDA membership.

An even deeper dilemma within NAMDA, of which some of its members are acutely aware, relates to the social goals after the end of apartheid. Some of the more radical members of NAMDA, including several of its leaders, feel that the struggle to overcome apartheid is only one aspect of a much more far-reaching class struggle. They feel that little would be gained if, when the apartheid system ends, a new oppressive Black elite replaces domination by the Whites. They have seen how, for example in Zaire, wealthy Blacks have seized power and continue to exploit and perpetuate the suffering of the impoverished masses. They have seen how even in Zimbabwe, which proclaims to be a socialist state, redistribution of land and wealth has been far too slow and that still (in the words of the taxi driver who took me to the airport upon leaving that country), “Not that much has really changed: the rich keep getting richer and the poor poorer.”

NAMDA’s Stand Against Apartheid

The National Medical and Dental Association (NAMDA) was formed in 1992, by a group of progressive doctors and dentists who lead broken away from the conservative Medical Association of South Africa (MASA). One reason for their break, was MASA’s lack of response to the death in detention of Steve Biko in 1977. (Biko was a leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, which in the late 60s and ’70s led a national awakening of Blacks to assert their dignity and rights.) The failure by NASA to take disciplinary action against two of its members (Drs. Lang and Tucker) for collaborating in the torture of Biko, led to a public outcry against the two doctors and against MASA. Many doctors resigned and later joined NAMDA.

According to Diliza Mji, President of NAMDA, “the formation of NAMDA heralded a new era in the history of professional organization. Unlike MASA, the aims of (NAMDA) were not concert primarily with the interests of doctors but with the broader socio-political issues of health and apartheid, how apartheid breeds disease, and the need to get involved in the day to day health struggles of the victims of apartheid, which range from community issues and trade lion work up to direct political activities.”

Some of the ways NASA tries to combat apartheid and cope with its consequences are as follows:

1. Political Prisoners

As the unrest in south Africa grows, political struggle involving workers; youth committees, schools, sand universities has escalated. The government has responded with a sweeping crackdown legitimized as a state of emergency.

According to a NAMDA report, “The state has used the emergency to detain thousands and to repress by brute force (shooting of civilians in townships) any resistance put up by the people. There have been initiated third degree methods to deal with opponents of apartheid (bombing of houses and disappearances).”

NAMDA has protested the detention without trial and routine abuse of the detained. In three cities it has set up panels of independent doctors to attend detainees. Although access to the: detainees has been reused, the doctors attend to their needs after release, NAMDA members Often risk their own security to defend the rights of and to document and expose the. violations to the detained.

2. Detention and Torture of Children

According to British Medical Journal Lancet,

The evidence that schoolchildren in, South Africa have been imprisoned and tired on a massive scale is overwhelming even whole school populations have been arrested.

NAMDA has tried to provide health, counseling, and support services to schoolchildren on their release. It has conducted a study of the effects on the children, many of whom have suffered both physical and psychological torture. Of children who were seen at one NAMDA clinic, 64% complained of assault and 73% had been detained for 20 weeks or more. 14% had been tortured with electric shock and 13% kept in solitary confinement. When seen, 57% had “psychological symptoms” and a third had “definable psychiatric ice.”

NAMDA has brought these abuses to the attention of the public, both nationally and internationally. Dr. Wendy Orr sought an injunction to stop prison authorities from ill-treating detainees. (As a result she lost her job as district surgeon in Port Elizabeth and was refused reemployment elsewhere). At a conference in Zimbabwe in June 1986, on “Repression of Children in Apartheid South Africa,” she made the following challenge:

Why the deafening silence [about torture]? Why is Dr. Ivor Lang, who carries the burden of Steve Biko’s death and the guilt of having ignored the assaults which 1 saw, now chief district surgeon in Port Elizabeth? Why [has MASA] not acted to bring doctors who do not report torture to task? And why the apathy and lack of sanctions from the world medical community? My challenge to the world medical community and to world medical associations is to take up the issue of torture and detention and the passive role of acceptance that South African doctors play.

3. Emergency Services

With the increase in political violence, NAMDA has recognized a great need for teams of neighborhood health workers to attend to the victims.

These emergency services are needed as a result of a number of circumstances:

-

During major rallies and protests people become victims of police action through tear gas, clubbing, and shooting.

-

Hospitals have become unsafe for any bullet wounded person because they are arrested on the assumption that they were shot by police for political crimes (rioting, demonstrations). Therefore injured people tend to stay away from the hospitals, running risk of complications and death froth their injuries.

-

During unrest situations, whole townships are sometimes sealed off, and net doctors or rescue squads can enter.

In response. to these, situations, NAMDA and several of the Health Workers. Organizations have trained local community health workers as emergency assistants. They have also held seminars and prepared simple instruction sheets and booklets oft community management of emergencies from tear gas, rubber bullets, gun shot wounds, and other forms of violent repression.

4. Worker’s Health—Industrial Health

In South. Africa, industrial workers suffer 20 times the amount of deaths and disability froth accidents as do workers in the U.S. or northern Europe. Both safety measures and accident compensation are grossly inadequate.

NAMDA is collaborating with workers organizations and unions to

-

assist existing industrial health groups to function more effectively

-

mate awareness of the problems and needs among workers, doctors, the public, and the state authorities

-

collaborate with safety and screening projects

-

pressure for legislation of a national occupational health service that ensures adequate industrial safety and equitable primary health.

5. Empowerment of the People for Health

NAMDA recognizes that health depends on far more than doctoring and that freedom from want arid hunger will do more to build up a healthy community than any amount of curative services. It believes in empowering people in the community to take major responsibility for their oven and each other’s health. To this end, NAMDA has been working closely with health worker organizations to train community health workers, establish local health teams, and to help mobilize a progressive Primary Health Care Network to unite and strengthen community programs throughout South Africa.

6. The Struggle for a Non-Racial, Democratic South Africa

NAMDA states clearly that, “The social and economic system of apartheid is incompatible with the attainment of goad health and that therefore the policies of apartheid should lee opposed at all levels.”

NAMDA spearheads a national and international awareness raising campaign to educate and activate the public in relation to the danger to health caused by apartheid. It stresses that THE STRUGGLE FOR HEALTH EQUALS THE STRUGGLE FOR DEMOCRACY. As a part of its educational thrust, it has held many meetings and published a wealth of materials discussing the high cost of apartheid to people’s health, and of :mobilization strategies in the struggle for health, equity, and justice for all.

The Preamble of the Constitution of NAMDA

We accept the World Health Organisation definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

We believe that health is a basic human right which should be available to all the people irrespective of sex, race, colour, political belief, economic or social condition.

We commit ourselves to creating the conditions for optimum health which can only exist in a free and democratic society.

The New Black Elite—a Present and Future Threat to the Poor Majority?

As the South African Black majority begins to awaken and demand greater equality, the Whites in control have been forced to take some defensive strategic actions. One, of course, has been to declare a state of emergency with the banning of many organizations, assemblies, and demonstrations.

Another far more subtle defense strategy of the ruling Whites has been to create and co-opt a Black middle class, and to provide this ’new rich’ with enough status and privilege so that they align themselves with the conservatives, preserving the status quo rather than working for change. An increasing number of Indians, Colored persons, and even Blacks, are being recruited for training and employment as white collar workers and professionals. They have recently been given special opportunities for middle and upper class housing under a new provision for 99-year lease (still not total ownership).

The nursing profession is now predominantly Black, and yet the South African Nursing Association (SANA) remains extremely conservative. Also, more and more Black doctors are being trained. Wherever possible, they are recruited into the ultra-conservative government-affiliated Medical Association of South Africa (MASA).

One of the biggest problems in South Africa today, often making health services counterproductive, is the large number of private practitioners, many of whom misuse their medical license to grow fat on the misfortune of the poor.

A progressive young woman doctor, with whom I stayed in Capetown, told me of the fearful exposure she had had to private practice. After having just completed her internship, she had been sent to a small town to work in the office of a private general practitioner (G.P.) whose practice, she soon discovered, was completely unscrupulous. The G.P.’s offices were divided into the barracks for Blacks and the suites for Whites. The side for Blacks was grossly under equipped and the newly arrived young doctor found she was required to attend 70 to 100 patients per day. Her instructions were to “See them quickly and give each patient three oral medications and one injection,” regardless of their ailment. When she asked about the treatment of children with diarrhea, the G.P. snapped back, “three oral medications and one injection, same as the rest.”

When the young doctor asked, “But what about oral rehydration?” the G.P. retorted, “Never heard of it. Three orals and one injection.”

By contrast, on the other side of the building, the Whites had a carpeted waiting room and plush wards with all the most modern medical and diagnostic facilities—and they were charged accordingly. However most of the money made was from the poor Blacks, who were charged from 15 to 20 Rand per consultation, plus the cost of medications. In this way, the G.P. could collect up to 2,000 Rand (U.S. $1,000) per professional employee per day. Since the money was paid out of pocket without receipts, most of it was not declared for taxes.

For many of the G.P.s of South Africa, health care delivery has become a lucrative racket, contributing to the increased poverty, malnutrition, and poor health of its victims.

A substantial percentage of NAMDA’s membership consists of G.P.s (private practitioners). While most are more conscientious than the G.P. just described, many have created small kingdoms for themselves through their private medical practice.

Questions concerning the ethics of private practice and the disproportionately high earnings of general practitioners working in impoverished communities appear to be a delicate, little debated subject within NAMDA. Yet some of its members do feel very strongly that if the transition to a non-apartheid South Africa is truly to open the way to a healthy and more humane society, the question of economic and social equity is as important as the question of racial equality.

There is a belief among many of the NAMDA members, especially its leaders, and very strongly among the participants of the health workers organizations and associations, that the struggle for freedom in South Africa is not just a struggle against apartheid but is also a class struggle. Their goals are for a transformed South Africa that has class as well as racial equality, fair distribution of resources, and the same basic privileges and rights for all the people.

Highs and Lows in the Relentless Progress Toward Freedom

At present in South Africa, many of those committed to social transformation seem discouraged. In the 70s there was a rapidly building coalition against the oppression of apartheid. By the early 80s, many people were confident that the system of white supremacy would fall within 3 or 4 years. But with the return of the state of emergency in 1985 and again in June of 1986, with its censorship, increased violence, arrests of activists, prohibitions of public demonstrations, and closing down of progressive organizations, it appears that popular resistance has been seriously restrained.

But as the keynote speaker at the recent NAMDA conference clearly stressed, resistance and awareness still continue to grow. The power and unity of the people are further kindled by the outrageous prohibitions and violence that attempt to extinguish them. The State’s declaration of a “state of emergency,” though it temporarily tightens the reins and enforces apparent compliance, is politically and ethically an admission of defeat.

Even the optimists recognize that it will be a long, hard struggle. The divisive forces are real; the obstacles are great. Some people now estimate that it may take another 20 years for the apartheid system to fall. But the seeds of change have sprouted and are deeply rooted. The struggle may go through it highs and lows, but it continues to move forward. People awakened by the cry for liberation never sleep quietly until they are free.

[LARGE DETAILED TABLE MISSING HERE.]

During my short visit to South Africa, I met so many courageous people committed to the struggle for human rights that, in spite of the horrendous obstacles and repression, I left with a sense of hope and excitement. Within the apartheid system, and in spite of it, there is a growing, indestructible movement for justice and change, which reaches across the barriers of race, sex, and to some extent even class. Sooner or later the movement will and must win, because in it lies the very essence of humanity.

I would like to repeat my conviction that those of us outside South Africa who are committed to human rights and social justice must take as strong a stand as possible against the violent, racist South African government. We must support divestment, embargoes, and other sanctions against South Africa wherever possible. But we must be selective in our sanctions, so as to weaken the oppressors while doing all we can to support, strengthen, and promote those activists, Black and White, who are committed to the overthrow of apartheid and to forging a just, more equitable society. HW

Dear Friends—About the Shift from Local to Global

Some of you may find it strange that in this issue of our “Newsletter from the Sierra Madre,” which generally focuses on matters of health and empowerment in rural Mexico, we turn to events in South Africa.

This shift from local to more global concerns reflects our growing awareness of how small the Earth, as a sociopolitical unit, has become. You will recall that in our last newsletter (No. 18) we looked at how the well-being of a village family in the Sierra Madre is affected by growing of narcotics. We noted how this, in turn, is linked to international drug traffic, to the huge foreign debt of poor countries, and to the unjust world economic order.

The powers-that-be in the world today are linked through an increasingly sophisticated communications network. The art of economic and social control is fast becoming an international science. And for those who resist, the overt and covert techniques of terrorism, torture, destabilization and ’low-intensity warfare’, are remarkably similar in the campaigns of the U.S. government, the Philippines government, the South African government, and their various allies.

In the world today, it has become clear that isolated struggles for health and equality, even in a remote village or slum, are inseparable from the global struggle for a more just world economic and social order. Poor people in a single village will not gain control over the factors that determine their health and lives, until they join together with many others to bring about transformations at the national level. Similarly, a poor country that tries to answer to the needs of its people through advancing a more egalitarian system, will find that certain powerful nations try to prevent it from succeeding. We have discussed the close parallels in the ways the U.S. (Might is Right) government and South African (White is Right) government impose their selfish ideologies on their weaker neighbors.

Today the self-determination of many developing peoples and countries is in jeopardy. Just as poor persons in a village can find strength through unity, so the more progressive poor nations must join together and take a stand against their exploiters.

But for such a stand to have any hope of success, developed nations whose leaders have more of a social conscience must stand behind the people of poor countries to form a coalition of solidarity.

Equally important is for those of us who are citizens of an oppressive superpower, but whose first allegiance is to the world community, to join in the defense of all people’s rights. Only through a massive awakening of people in rich and poor countries alike to the need for new leadership, and a new nonexploitative world order, can our planet and our species hope to survive.

A Suggestion for those Committed to World Health

I am often asked by sincere young U.S. citizens (especially those who have majored in international health or development) what they can do or where they should go to best help the poorest and neediest in the world today.

Increasingly my considered response has become, “stay at home!” Or if you do go to a poor country, do so not to provide, but to learn. Learn what changes are needed in U.S. foreign policy—and U.S. lifestyle—so as to permit the world’s disadvantaged peoples a fairer chance at self-determination. Then come home to the U.S. and join the battle to awaken others.

Only when there is a massive organized demand for the humanization of policies within powerful countries, to match the swelling struggle for justice among the world’s oppressed majority, can we hope to forestall global annihilation, and begin to promote “health for all.”

Our chances for such global transformation may be small. The process must begin at home in small ways, and through a growing network of solidarity. The obstacles are daunting and the outcome far from certain. But the nature of the struggle itself, and the friendships it generates, makes it worth it. HW

Update: On the Role of the U.S. Government in International Drug Trafficking

The Results of Our Letter Writing Campaign

In our last newsletter (No. 18, September 1987) we discussed how Mexico and other disadvantaged countries have no choice but to depend on international drug trafficking just to keep paying the interest on their suffocating foreign debts. We pointed out that this dire necessity to service debt through drugs makes it very difficult for the governments of either the drug-consuming countries (notably the U.S.) or the drug producing countries, to fight a serious “war on drugs.” Far from curtailing drug flow into the U.S., the evidence shows that U.S. government agents have for 40 years been financing covert destabilization campaigns (that is to say, secret wars and terrorism) against small countries that have dared to distribute resources more fairly, and are therefore considered a threat to U.S. security. As a current example, we looked at Central America. We quoted nationally reported evidence that many of the U.S. missions to supply so-called “humanitarian aid” to the Nicaraguan Contras were in fact clandestinely delivering tons of arms and explosives to the Contras, and were transporting tons of cocaine and heroin into the U.S. on their return flights. We also quoted allegations that certain high U.S. officials were aware of this U.S. Contra drug connection and that some actively promoted it, while others contrived to cover it up or provide ‘deniability’.

Newsletter No. 18 was sent to subscribers in nearly 100 countries, and (with a cover letter) to every member of the U.S. Congress. The response from our readers was tremendous. Some sent for 100 copies or more to distribute to concerned groups and friends.

By contrast, the response from the members of Congress was disappointing: a handful of inappropriate form letters.

We did get a long and enthusiastic response from Rep. Charles Rangel, who heads the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control.

The Head of the U.S. Justice Department Obstructs Justice—Says U.S. Congressman

In his reply and accompanying documents Rep. Rangel expressed his frustration with the U.S. Justice Department, the CIA, and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) for obstructing attempts by his Congressional committee to get at the root of the U.S.—Contra-drug connection. In May of 1987, Rangel requested that the DEA, CIA, and Customs Service brief his committee on Contra drug links at a closed session. The CIA and the DEA, which is under the Justice Department, refused. Rangel charged that Attorney General Meese had “gagged” these agencies. “We are being stone-walled,” Rangel said.

It is a sad state of affairs when the head of the U.S. Justice Department obstructs justice in a matter that concerns not only the health and well-being of millions of young North Americans, but the stability of other nations and the prospects for world peace.

The U.S. Mass Media—Accomplice to Government Crime

Equally sad is the apparent conspiracy of the major U.S. press in the cover-up. Even the Washington Post (which has often been braver than most in exposing abuses by the U.S. government) is guilty of suppressing this explosive and far-reaching issue.

On July 22, 1987, Rep. Rangel sent a letter to the Washington Post criticizing as misleading an article that appeared in the Post the same day, “Hill Panel Finds No Evidence Linking Contra to Drug Smuggling.” In his letter to the Post, Rangel stresses that the Congressional Committee he heads, in fact, reached quite a different conclusion. He states clearly that “We did not conclude that there was no Contra involvement in drug smuggling.” He adds, “equally important, we are investigating the possibility of U.S. federal agencies’ acquiescence in or knowledge of Contra drug smuggling links and the use of any proceeds of drug trafficking to support the Contra cause.”

The Washington Post refused to publish Rangel’s letter, relatively cautious as it was, considering the wealth of incriminating evidence. So Rangel published the letter in the Congressional Record.

Within certain government circles (and some of the more conservative U.S. press) there has been an active attempt to discredit Representative Rangel and the findings of his committee.

For example, a June 6, 1988 article of the New York Times relates other congresspersons’ criticism of Rangel, accusing him of being “dogmatic and demagogic” in his pursuit of drug enforcement. It criticizes him for “taking the hard line and popular view that we’re not being tough enough and that’s why we’re not winning the drug war.”

But the Times article does not tell us that it is on our own government that Rangel wants Congress to be tougher. Nor does it breathe a word about the countless allegations of crime, dishonesty, and high-level cover-up of complicity in drug trafficking by U.S. agencies or the House committee’s substantiation of many of those allegations.

Rangel’s committee has made these earth-shattering facts clear. Why hasn’t the New York Times? We find ourselves asking, “What are the vested interests of the paper’s owners and editors?” “What do you suppose the CIA or IRS has on them?” Who decides what news is “fit to print?”

To make things worse, the Christic Institute’s case to expose the involvement of present and former U.S. agents in drug trafficking to finance covert violence, was recently thrown out of court. However, the Christic Institute is continuing its fight and still needs support.

With both the media and the justice system conspiracy to cover up the drug trafficking and terrorism of the U.S. government, those of us committed to defending the interests of the oppressed must take a stronger and more united stand than ever.

Short Notes

TOBACCO: From ‘World Development Forum,’ Volume 6, Number 11, June 15, 1988

Colombian Cocaine and U.S. Tobacco: “Despite our great concern about the effect of Columbian cocaine on young Americans,” said Dr. Peter Bourne, president of the American Association for World Health, “more Colombians die today from diseases caused by tobacco products exported to their country by American tobacco companies than do Americans from Colombian cocaine.”

TOBACCO: From CUSO Newsletter, Fall 1987

In the Third World, the prospect of a fast cash return from a tobacco crop can be irresistible to poor farmers. It is equally irresistible to their governments. Taxes on cigarettes accounted in 1980 for 47 percent of government income in the Philippines. Is it any wonder that the country also refused to print health warnings on cigarette packs?

POEM: From Two Dogs and Freedom (1986)

Children from the South African townships express their feelings in words and pictures.

“Freedom for the People” author is a 12-year-old boy

Life in nowadays is like a sick butterfly.

To many of us it is not worth living when it is like this.

What is going on in the world around us.

There are people dying.