Report from the Philippines

Introduction

In November 1986 I went to Nicaragua to attend the Fourth Annual Nicaragua/North America Colloquium on Health. I had been working for Hesperian on a manual on midwifery for use in the Third World, and went to the colloquium to meet people, especially traditional midwives and community health workers, to learn a little more about the Nicaraguan situation, and to give a presentation on childbirth education.

One of the participants in the conference was Sylvia, a doctor from the Philippines. She was a small, round, good-natured, very intelligent person. I liked her. Trying to be friendly and make conversation, I asked, “Oh, you’re a doctor? Do you have a medical specialty?” “Why yes, l do,” she replied, giving me a cheerful smile. “I specialize in the rehabilitation of torture victims.”

Three years later, the first draft of the midwifery manuscript is finished, and I am facing a new task: how to evaluate all the feedback and criticism we have received from around the world and integrate it into the revision.

And, even more important, how to take this raw material and turn it into something that is as useful and as easily accessible as possible to health workers and midwives, and something that is culturally appropriate in a variety of settings. I explain this problem in a letter to Sylvia (who has in the meantime become a friend and one of the reviewers). She writes back with an intriguing suggestion.

Two months later I am on a plane to Manila. Gabriela, a 50,000-member progressive women’s organization, has invited me to come teach a course on basic midwifery for midwives and health workers from poor urban and rural areas. I will start by receiving a two-week orientation to the health situation in the Philippines, will then teach for a month (during which time I will also be “field-testing” the manuscript), and will wrap up my stay by spending a couple of weeks in the countryside and conferring with Sylvia on the book. This article is a summary of some of my impressions and experiences during my visit.

Sex Work in Olongopo

Between 11,000 and 17,000 “prostituted women” here service the US Subic Bay Naval Base. I am still under-going my orientation, which includes visits to various health sector and women’s organizations, as well as to several urban poor communities. Today I have made the journey here from Manila with a companion to be exposed to this aspect of the situation in the Philippines. Gabriela has created a “Commission on Violence Against Women.” Here in Olongopo this Commission has set up the Bulkod Center for Prostituted Women, which teaches the women English and other skills, raises consciousness about the rights of prostitutes as workers, provides health education workshops and counseling, and offers a “night care center” for the children. When a prostitute gets pregnant and is kicked out of the bar where she works, she can stay at the center.

Two women, one a former prostitute, the other still working as one, come to act as our guides and take us around to visit the bars. I am trying to put myself in a frame of mind that will allow me to feel and understand the experience of these women, and I find myself doing the same towards the American servicemen I see in the street. What is it like for them to be here? I am especially intrigued by the black servicemen. What does it feel like to suddenly be one of the oppressor class? I watch their faces, wondering.

The whites and blacks have separate bars. They are not segregated, but are different. The first two bars we visit are white bars. There is a long counter for serving drinks. On one side are barstools, tables, and chairs. Men sit in groups or with Filipino women, drinking, talking, laughing, or watching the stage. This platform is located on the other side of the counter. On it are 10-15 women in bathing suits or leotards dancing listlessly, making sexy gestures, or just sort of standing there. Mary, one of the guides, tells me that many of the women take valium just to get up the nerve to go on stage. The men watch and shop. Some look like real jerks, but most just look like ordinary guys. Some look young and rather sweet. Watching them, I get the clear sense that they think they are looking at “dolls”—exotic “China” dolls.

If a man wants to talk to a woman, he can buy her a drink (she gets a percentage—perhaps a dollar). At one of the bars a small Filipino woman is sitting on the lap of a large white GI (he looks like a Marine to me). She is maybe 16 years old, maybe 20. She is half his size—by weight probably less than half. He whispers in her ear and she laughs. He puts his arms around her; she is still smiling, but I see her shoulders hunch…

What makes the poverty so grinding is the total lack of backup. There is no welfare, no medicare, no food stamps. If you get sick, it's too bad.

If a man wants to “take a woman out,” he must pay a “barfine” to the bar to do so. Again, she gets a percentage—perhaps four dollars, it depends. After several loud disco songs, the group of women leaves the stage and another batch comes on. If a woman is not chosen, she receives only 40 pesos, or about two dollars, for a night’s work of standing, dancing, and waiting.

This is a tame week. Over and over I’m told that right now there is “no ship,” and therefore the bars are patronized only by the men permanently stationed at the base. A ship may bring in 9,000 men at a time. Then things get pretty wild, with live sex shows on stage, and things like that. In one popular act, a woman sucks coins out of a bottle with her vagina. Mary says that when there is no ship, there is no money, and things can get pretty hard for the women. There may not be much to eat.

At one point a lone black man comes into the white bar. He sits at a table in the back and watches with a grim expression. He drinks one beer. He does not smile. After about 15 minutes, he leaves.

Visiting a Black Bar

Later we visit a black bar. The women here are also working, of course, but the atmosphere and the physical environment are different. There is no “China doll” feeling here. The stage has been replaced by a dance floor, and the music is more rap and less disco. Men pick partners by dancing and socializing freely among the women. It is a tribute to racism that it took me a full 24 hours to figure out why the setup in the black bar is so different. The music is obvious, a matter of cultural preference, but why no stage? Then it hit me: the image of brown women standing on a platform being looked over and bought by white men must be profoundly disturbing to the blacks stationed at Olongopo.

Back at the center, I ask about AIDS prevention and birth control. There are over 52 known cases of HIV infection, virtually all among women who service the US bases. The Philippine government wants the US to pay for the medical care of these women, but the US refuses. Most of the infected women probably won’t get care, at least not much. Some have disappeared—gone home, perhaps, or left Olongopo to continue their work in some area where no one knows of their condition.

Condoms are available, but some men won’t wear them, and some women don’t like them because the say they hurt. Lubricants such as spermicide or Kare too expensive. Natural lubrication is, I assume, absent due to the woman’s lack of enthusiasm for paid sex. [Editor’s note: Condoms absorb natural lubrication, and generally require added lubricant.]

Like so many developing nations, the Philippines is very much under the thumb of the International Monetary Fund and other creditors . . . To pay its debts, it must place social services and political reforms on the back burner.

Abortion is illegal here. A woman who needs an abortion must go to a traditional midwife for services. The midwife squeezes the womb until she dislodges the pregnancy, or else puts a catheter up through the cervix into the uterus and leaves it there for several days to cause a miscarriage. The first person I ask, “Do you know anyone who ever had a problem with one of these abortions?” answers, “Yes, I have a friend who died of one last year.” (In fact, during the midwifery training, almost every time we studied a complication of pregnancy or birth, someone would say, “Yes, I know someone who died of that.”)

It’s mostly poverty that drives women into prostitution. The poverty I see in the urban squatter communities is appalling. It’s not just the little handmade houses patched together from this and that, sometimes huddled between factory and railroad tracks, or perched on slender poles over the polluted rivers. Actually, the houses have a certain charm. They are creatively built and surprisingly solid inside (though I worry about how well they would hold up in a typhoon).

No Support for the Poor

What makes the poverty so grinding is the total lack of backup. There is no welfare, no medicare, no food stamps. If you get sick, it’s too bad. If you have no food, it’s too bad. If your kid gets hit by a bus, or grows up disabled or blind from lack of vitamins, it’s too bad. I would say that about a third of the children I saw in the poor urban communities I visited were visibly malnourished and/or ill. Many communities have no plumbing. Clean water must often be hauled in from a faucet several blocks away. And it’s not always so clean. For those who are better off, the toilet may consist of a porcelain bowl that is flushed with a bucket by hand. For others, it is a rickety box with a hole in the bottom suspended over the river. You pee through the hole into the river. Squatters may live in such a community for years, yet they can be kicked out by the landowner at a moment’s notice.

The countryside is very beautiful, but I’m told that the poverty there is often even worse than it is in the cities. Large landholders own the best land, and the poor must sharecrop or grow rice on little paddies up m the mountains. Also, there is a war going on. The Philippines is embroiled in a protracted struggle similar to those in El Salvador and Guatemala. Recently, the Aquino government has been forcibly relocating peasants in many areas from their villages to camps where little food or medical care is available. The purpose of this policy is to allow the military to go into the countryside and hunt Communists.

There was much hope, I think, when Aquino first came to power. But many people I talked with had become disillusioned, saying that her Administration has not instituted much in the way of meaningful programs or reforms, and that regression continues. For instance, early in her administration a group of farmers marched to the National Palace to demand agrarian reform, only to be gunned down by the military.

Philippines Under the Thumb of International Capital

One obstacle to progress is the fact that, like so many developing nations, the Philippines is very much under the thumb of the International Monetary Fund and other creditors. To obtain international aid, the country must pay its debts. To pay its debts, it must place social services and political reforms on the back burner. Too much dissent can lead to detention, assassination, or worse. The price of rice keeps going up. And even when wages rise, they remain abysmally low. At present, though I twice saw gold Mercedes driving through these same streets, at east 30 million people in the Philippines—over half the population—live in abject poverty.

In response to this situation, there are a great many NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) doing impressive work. I visited MAG (Medical Action Group), which provides rehabilitation services to survivors of torture and offers medical care to families displaced by the war, as well as to the families of the disappeared and politically detained. HEAD, another NGO, provides medical services at rallies, marches, and demonstrations. HAIN is a large primary health care library which also produces publications dealing with the health care situation in the Philippines. I also visited a union office for hospital health workers, as well as a center for herbal and traditional medicine located in a squatter community. Then there was BUNSO (see below) and the Commission on Violence Against Women, and on and on.

I remember at one point complaining to a friend of mine there: “I’m very interested in all the political groups, of course, but what I really want to do is get my hands into primary care. I like visiting communities and working with the people.” She replied, “But there can be no real change without the political work.” Then she dropped her eyes and said softly, “We all started out doing primary care.” Some time later I learned that one of her close childhood friends had been murdered by the military at age 16 for doing primary health work among the poor. (This was during the Marcos days, but such things continue to happen under the Aquino government.)

Efforts to deal with problems directly are still often thwarted by the government or the military—especially if these efforts have a political flavor. In one community I met the pregnant wife of a young health worker/community organizer who was in jail because he had attended the funeral of another health worker who had been assassinated. The woman was trying to raise the money for the bail, which was an enormous sum for such poor people. Her husband had helped organize the construction of a latrine and sewage system in the community.

Visiting BUNSO—Promoting Breastfeeding

BUNSO (it means “youngest child”) is a large organization that promotes breast feeding. It goes into poor communities and trains mothers to teach others about breas feeding and baby care. In one community I saw, it has set up a food supplement co-op. It does organizing work on issues affecting mothers, babies, and children. Recently, I am told, several breast feeding teachers were arrested, charged with being subversives, and thrown in jail. After spending some time there, they were finally released.

I was appalled by the number of infant formula ads on television. * Next to electric fans, there seemed to be more commercials for this than for any other product. At least, thanks to BUNSO’s efforts, the ads no longer target newborns, but are limited to babies over six months. Nestle, which ran ads for its coffee products as well as for its infant’s/children’s milk, appeared to be the single biggest overall advertiser.

* In 1984 Nestle, under pressure from an international boycott of its products, agreed to abide by the World Health Assembly’s International Code of Marketing. However, violations of this Code have prompted a renewed boycott against Nestle and American Home Products, another major infant formula producer. For more information, contact Action for Corporate Accountability, 3255 Hennepin Ave. S., Suite 230, Minneapolis, MN 55408, USA.

At the same time that they suffer difficulties and harassment, some of these organizations do receive some support and respect from the government. Many receive funding from international agencies such as UNICEF. I was also very impressed by the strength and level of organization of these groups, and by the degree of cooperation among them. In these respects they put us here in the US to shame.

Finally the orientation was over and it was time for the training to begin. We had about 16 students (two dropped out and two joined late). One woman was a “Hilot,” or traditional midwife. We also had three government-trained midwives who had each completed a two-year hospital course. Most of the others were community health workers who were getting their introduction to midwifery in this training. All could read. Formal schooling ranged from the third grade (our Hilot) to a couple of years of college. But the average seemed to be about six years of school. The participants came from all over the Philippines.

What good does it do to give dietary advice when there is no money for food? Or to teach cleanliness when there is neither soap nor clean water available?

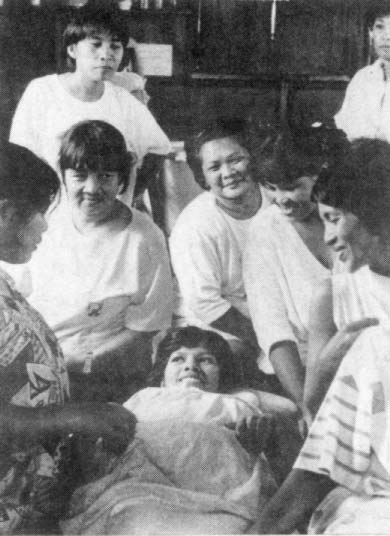

We spent the first two weeks on prenatal care. We used lectures, slides, sewn teaching aids (like a cloth placenta and even a cloth pelvic bone), demonstrations, illustrations, and role-playing. To role-play a prenatal exam, a participant would be given a slip of paper describing a situation. For example: “You are 26 years old. This is your third baby. Your last period was December 4. You are having some pain m your lower belly and a little bleeding.” Then we would take a doll of the appropriate size and put it under her shirt, and pin a paper belly button at the appropriate level on the outside of her shirt. (The relationship of a woman’s belly button to the top of the uterus is one way to tell how pregnant she is.) Another participant would play the role of the midwife: take blood pressure, work out the due date, feel the belly, do an interview, and decide whether there was a problem and what to do about it. Sometimes we put the doll in “breech,” or set the doll size and belly button position for a date that conflicted with the calculated due date, and the students would have to figure out why. It was a lot of fun.

We also had two pregnant women in the training, who let us practice feeling their babies’ position and doing real prenatal checkups before we went to work on women in the community. One of these was the nurse, Besing. The other was a Belgian obstetrician, Rita, who was working as a volunteer in the Philippines and assisted with the class. We also practiced other skills (such as taking blood pressure) on each other.

Community Prenatal Day

About two weeks into the training, we held a “Community Prenatal Day” in a squatter community named Apelo Cruz. About 15 women came, and the students took blood pressures, felt bellies, and did interviews. In a healthy population one might expect to find one or two women out of 15 with some kind of problem requiring special attention. In this group we found only four women who did not have a problem needing special attention (and they were all young women having their first babies). About five women were suffering from moderate to severe problems related to hypertension (high blood pressure/pre-eclampsia). One woman had a blood pressure of 170/110, which is extremely high for an 18-year-old pregnant woman. This woman also had a urinary tract infection. She had been experiencing symptoms for several months, during which period she had been going in for regular prenatals at a public clinic -apparently nobody had noticed. We found her problem during our routine interview.

Another four or five women had urinary tract infections. One woman had strange sores all over her body. One had lost her last baby after the birth, but did not know why. One, a tiny woman with a small pelvis, had undergone a previous C-section. This time the baby’s head was not in the pelvis at all (not head down), but up and off to the side—a sign of a baby too big (or pelvic bones too small) to fit. Small bones can be simple heredity, or the result of malnutrition in childhood. I do not know which was responsible in her case.

But what struck me the most that day, beyond the fact that statistically this was all wrong, was the realization that no amount of medical training or knowledge of the sort I was trying to share with these people is going to get to the root of the problem. What good does it do to tell a woman with high blood pressure to get bed rest if a day’s missed work means that she and her family won’t eat that night? What good does it do to give dietary advice when there is no money for food? Or to teach cleanliness when there is neither soap nor clean water available? Or to send people to a public clinic (assuming there is one) if, again, a day’s missed work means no food, and medicines are too expensive to buy? The women told me that sometimes they go to the public prenatal clinic and wait all day, but neither the doctor nor the nurse shows up. Clearly, something very fundamental has to change, and while the health work we do does save lives and improve people’s physical and even emotional well-being, it is the unfair distribution of wealth and power that is really making these people ill.

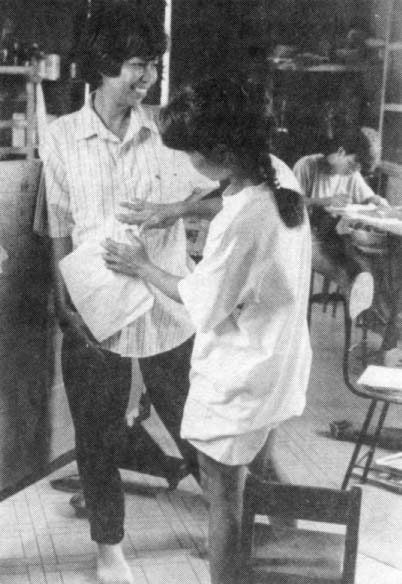

After the prenatal section of the workshop, we tackled labor, birth, and complications. We used local resources for teaching. For instance, to demonstrate what the uterus should feel like after childbirth, we had a woman lie down, placed a coconut on her stomach, and laid a sheet of foam over it: this simulated a well-contracted uterus felt through the flesh of the belly. To demonstrate an uncontracted uterus and to teach how to massage the belly to prevent hemorrhage, I lay down next to her and had people feel my soft belly and showed them how to rub it up. Then they felt the coconut to see the difference.

Looking back, it is clear that we did not leave enough time for this part of the training. It was too much to squeeze into such a short time, and we should have arranged some way to take participants to real births, especially those without prior experience. This could have been done if we had allotted a little more time, and held prenatals regularly in a particular community from the first day (thus getting to know the women and finding some who wanted us present at their births). Still, we covered a lot of ground, and people were pleased. The experienced midwives felt that they had added considerably to their knowledge and skills, and the novices felt that they now had a good foundation to build on. I learned much that will be helpful in revising the book—and also in life.

After the training the participants went back to their respective communities to begin or continue working m women’s health. The local organizations will be providing follow-up, while the participants will be sharing what they learned with others m the community.

With this phase done, I spent a week editing the book with Sylvia, and then went off to Mountain Province to meet with midwives there. Some of them had between 10 and 14 children of their own! One, Romana, told us that she had given birth to most of her babies alone without any help at all. “In the morning my husband would wake up and say, “Well, did you have the baby last night?,” and I’d say ,”Yup.”’ She was quite incredible—very strong. What must it be like to live “close to the earth” in a place where your ancestors have been for thousands of years?

Final note: The US lease on the Subic Bay and Clark military bases in the Philippines is up for renewal in September 1991. Already Washington is pressuring President Aquino to renew it despite widespread opposition and the belief that the presence of the bases makes the Philippines a nuclear target. Getting rid of the bases will not end poverty, oppression, or prostitution in the Philippines, but it is a start— a necessary, though not sufficient, condition. We in the US can help by demanding that our government get out of other people’s countries. So keep informed, write letters to your representatives and to the media, raise consciousness, join protests, and contribute money to or volunteer with groups working on these issues. HW

Nicaragua: What Does the Election Mean?

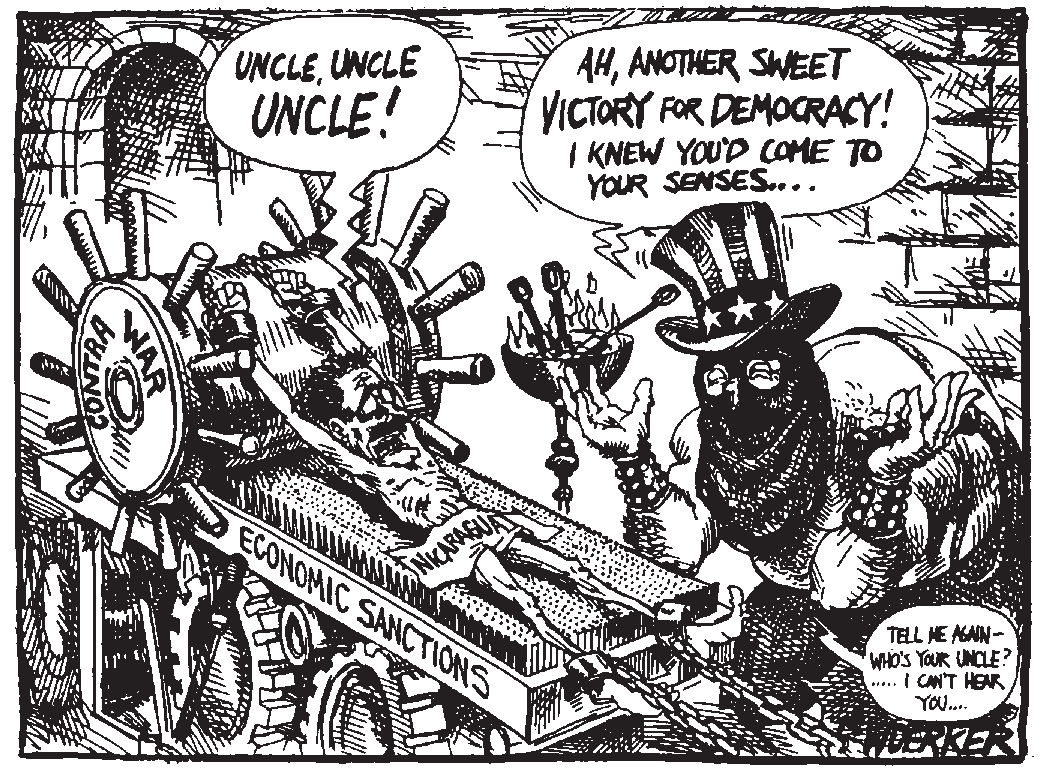

The lesson of the Nicaraguan election is simple: the US government can bully and buy its proxy into power in a small, desperately poor Third World country. The US engineered the victory of the United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO) in three ways:

-

It held a gun to the head of the Nicaraguan people, making it clear that they could choose between electing UN0 and suffering six more years of war and devastating economic sanctions.

-

It bribed and arm-twisted fourteen disparate parties united only by their opportunism into forming a single opposition coalition, changing a multi-party race in which the Sandinistas would have held a commanding plurality into a two-party contest.

-

Using a variety of overt and covert channels, it poured up to 26 million dollars into the coffers of UNO and its supporters. (A clear double standard was at work here, since foreign campaign contributions are strictly prohibited under US law.)

Any incumbent government in the world would have trouble winning an election when saddled with a prolonged, bloody war (which in turn prompted the Sandinista gov rnment to introduce a highly unpopular draft) and—even more decisive—a catastrophic economic situation summed up in an annual inflation rate measured in the thousands. Sticking with the FSLN under such circumstances would have required a very advanced level of consciousness—one much higher than most of us North Americans can claim to possess. In fact, it is an impressive tribute to the resilience and sophistication of the Nicaraguan people that over 40 percent of them still cast their ballots for the Frente.

Why is the Nicaraguan economy in such shambles? The most immediate factor is the Contra war. Sandinista mismanagement also contributed to the debacle, although to a much lesser degree; while the revolutionary government’s policies were in many cases sound, it often simply lacked the trained personnel required to implement them effectively. But the more basic culprit is the economic crisis affecting so many Third World countries, marked by declining terms of trade and heavy foreign debt, which meant that the government was in effect dealt a losing hand, no matter what economic policies it adopted. The sharply divided opposition has no coherent program for resolving this fundamental problem, and all the US aid in the world is not going to make it disappear.

In fact, the imposition of the US-favored free market economic strategy—which Washington is certain to make a prerequisite for any meaningful aid—will most likely only worsen the plight of the poor, as has been the case in most other Third World countries. How can anyone aware of the grievous human toll this approach is taking in such countries as Mexico and Brazil, where real wages and nutrition standards have been rolled back to 1960s levels, seriously hold it up as a model?

Moreover, the Bush Administration is unlikely to pump in enough aid to make a lasting difference, especially given its new commitments in Eastern Europe: the proposed $300 million package will barely put a dent in the economic damage and lost production caused by the US destabilization campaign. And US funds are likely to be overwhelmingly targeted at the private sector and wealthy business interests at the expense of the poor majority and equitable development. Those who assume that the US can be counted on to bail out the Chamorro Administration should take a look at the precedents of Grenada and Jamaica, where Washington also played a key role in toppling progressive regimes; after promising the sky, the US failed to deliver sufficient or appropriate aid to its newly installed clients, and both countries are now economic basket cases.

Do the Nicaraguan election results mean that Washington finally won, that after a decade of destabilization and low intensity conflict it at last succeeded in making the Nicaraguan people say “uncle”? Yes and no. The US lacked the power to achieve its optimal scenario: the military over-throw of the Sandinista government (either by the Contras or, if necessary, by an outright US invasion), which would have been followed by a brutally thorough dismantling of the FSLN, its mass organizations, and all the country’s other popular forces, entailing massive repression and loss of life. The US solidarity movement can be proud that its efforts to mobilize public opinion played a key role in averting this outcome.

Health Care in Nicaragua: Gains of the Revolution in Jeopardy

From the start, Nicaragua’s revolutionary government placed great emphasis on popular health care. The Sandinistas inherited from the Somoza dictatorship an under funded, inefficient hospital- and physician-centered health care model which catered to the tiny urban elite while completely neglecting the needs of the country’s poor majority. They quickly replaced this system with a network of health centers and posts that brought almost entirely free services to the most remote rural areas and the poorest Nicaraguans. Moreover, thanks to the revolutionary government’s capacity to mobilize massive popular participation, it was able to conduct a series of extremely successful nationwide vaccination health education campaigns.

The result of all this was that Nicaragua made remarkable progress in improving its people’s health, particularly in the early years of the Revolution. From 1978 to 1983 infant immortality decreased from 121 to 80.2 per 1,000 live births, life expectancy rose from 52 to 59 years, diarrhea fell from first to fourth place as a cause of hospital mortality. * The Sandinistas’ health achievements won praise from the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization.

As the years went by, however, the US government’s relentless destabilization campaign began to erode the Revolution’s health accomplishments. Washington’s trade embargo and credit boycott drastically reduced the amount of foreign exchange for purchasing medicines and medical equipment abroad, while the US-sponsored Contra war forced the Sandinistas to divert precious economic and human resources from the health care sector to defense. Most directly, the Contras singled out health care facilities and personnel as special targets of their attacks, seeking to undermine the popular support they generated for the Revolution. Through 1984, the Contras had destroyed or forced the closing of 50 clinics, and had killed 72 health workers. * * Many more health workers were wounded, kidnapped, or tortured. Even in the face of this systematic onslaught, the Sandinista government managed to preserve most of the major health gains that had been won; only in the late ’80s, for instance, did child mortality again begin to rise slightly.

It is too early to know how the change of government in Nicaragua will affect its people’s health. The Bush Administration’s $300 million aid package earmarks only 14 million for the health care sector—less than half the amount it allocates to repatriating the Contras. The newly elected UNO government and the US are likely to push for the privatization of the health sector and for policies that make the practice of medicine highly profitable for private doctors, hospitals, and drug companies. As a result, health care will probably became more expensive, more skewed toward urban areas, and less accessible to the poor majority. In fact, if the Chamorro Administration pursues the kinds of policies its Washington patron desires, Nicaragua’s health status may well descend to the abysmal levels that prevail in such US client states as Honduras, El Salvador, and Grenada.

* Richard Garfield and E. Taboada, “Health Serviced Reforms in Revolutionary Nicaragua,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 74,No. 10 (October 1994), p. 1138.

* * Ibid.

After decades of almost uninterrupted suffering and sacrifice, the Nicaraguan people have opted to take a well - Deserved breather.

But, tragically, Washington still wielded sufficient clout to be able to prevent the Nicaraguan Revolution from realizing its potential and blossoming into a “good example” for other Third World nations to follow—and to punish the Nicaraguan people savagely for their refusal to bow to its dictates (over 30,000 killed in the Contra war, tens of thousands more maimed or killed indirectly due to the effects of the war and US economic sanctions). However, how severe and permanent a setback it has been able to inflict remains to be seen.

After decades of almost uninterrupted suffering and sacrifice, the Nicaraguan people have opted to take a well-de-served breather. But UNO, which has never issued a coherent platform spelling out what it stands for, and its US patron should be careful not to misinterpret the election’s message. If the Chamorro Administration tries to roll back the Sandinistas’ legacy of accomplishments and ideals—agrarian reform, improved literacy and health care, self-determination, and a firm commitment to defending the rights and interests of the country’s poor majority—it will encounter a spirited and organized popular resistance.

The Nicaraguan Revolution is a historical fact that cannot be erased, much as those in Washington would like to do so.

The FSLN remains by far the most popular and best-organized political party in Nicaragua. It draws strength from a formidable network of grassroots activists and mass organizations, lending credence to Daniel Ortega’s claim that the Frente will be able to “govern from below.” What is more, the FSLN can count on an army, police, and local militias firmly grounded in nationalist, Sandinista ideals, which will make it very difficult for the US to reestablish a force like the Somoza dynasty’s National Guard which could be used to enforce unpopular policies and repress the Nicaraguan poor. (It is ironic, but predictable, that Washington, while apparently unconcerned about the threat posed to emerging democratic processes in Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, etc. by still-powerful right-wing military establishments, is lobbying strenuously for the disbanding or “depoliticization” of one of the very few armies in Latin America that actually plays a progressive role.) The Nicaraguan Revolution, then, is a historical fact that cannot be erased, much as those in Washington would like to do so.

In fact, given the likelihood that the UNO coalition will fail to live up to the Nicaraguan public’s expectations for a miraculous economic recovery, antagonize the country’s poor, wallow in corruption, or simply come apart at the seams due to internal strains, many Nicaraguans may soon be looking back fondly on the days of Sandinista ascendancy. They may decide that, if US policies—whether hostile or “friendly”—and an unjust international economic order condemn them to suffer in any case, they might as well suffer with dignity, while upholding an ideal and pioneering an alternative, more compassionate development model.

So, while it is clearly much too early to make any predictions, the FSLN would appear to stand a very good chance of winning the 1996 elections. Something similar happened recently in Jamaica, where the progressive, nationalist leader Michael Manley was voted back into power after losing the previous election in the wake of an intense US-or-chestrated destabilization campaign (though, fortunately, it is hard to imagine the FSLN compromising its principles as drastically as Manley’s People’s National Party has done). If the Sandinistas manage to duplicate Manley’s feat, they will gain an unprecedented double legitimacy, becoming the first revolutionary movement ever to win power twice, first through a popular insurrection and then, following a stint out of office, through a free election.

In the meantime, concerned citizens in the US have a more important role than ever to play. We must pressure Congress to allocate aid in forms and through channels that promote genuine, equitable development and that help, rather than hurt, the Nicaraguan poor. We must monitor and curtail US meddling in Nicaragua’s internal affairs, which will assume a more insidious form now that a client regime is in power there. And we must prevent the Bush Administration from exploiting the sharp conflicts that will inevitably occur as supporters of the Revolution struggle to defend its gains as a pretext for refusing to disband the Contras or launching a direct military intervention.

Update on Human Rights Abuses in Mexico Resulting from the ‘War on Drugs’

In our last newsletter, we described how a number of men and boys from the small village of Lodasál, located near Ajoya in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, were dragged out of their beds in the middle of the night by a group of soldiers from San Ignacio who accused them of growing drugs. Some of them were severely beaten and tortured, while others were thrown in jail on trumped-up drug charges.

Since Newsletter #20 came out, the soldiers in the area have become even more brutal in their detention and roughing up of innocent people. In January they stopped a young man walking on a footpath outside the community of San Ignacio and, in the process of trying to force him to confess to growing drugs, beat him so badly that his intestine was rupture. The soldiers left the man unconscious beside a river, where he was found by some villagers. They transported him to the hospital in Mazatlán, where he underwent surgery.

The young man’s family lodged a complaint with the new municipal president, who brought the matter to the attention of the general in charge of the army detachment based in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa. The local newspapers also reported on this latest human rights violation. A newsaper called Debate published a particularly scathing response, accusing the soldiers of San Ignacio, commanded by a Lieutenant Victor Hugo, of using the “war on drugs” as a cover for terrorizing, torturing, falsely accusing, and extorting money from innocent citizens.

These protests came on the heels of the ones we had made after the raid on Lodasál. We had approached the same general, who had disclaimed all responsibility for that incident and refused to take any action. However, we had also taken our case to the newspapers in the area, which had run articles on the story, and to a human rights organization based at the Culiacán university, which had proceeded to contact the general in its own right.

Apparently the mounting pressures coming from all directions finally led the general to go to San Ignacio and conduct an investigation. As a result, Lieutenant Hugo is now in jail, and has been ordered to pay the three million peso ($1,000) hospital bill for the man who was beaten and left for dead. A few days later Liberato Ribota Melero, the one resident of Lodasál remaining behind bars, was summoned over the loudspeaker in the huge federal penitentiary outside Mazatlán. After five months in jail, he was summarily told that he could leave. This was followed shortly by the release of a health worker and his son from a nearby village who, together with some other men, had been arrested by soldiers six years ago on false drug charges while playing volleyball on a Sunday afternoon.

So the whole Ribota family is finally free (one of Liberato’s sons had also been imprisoned for a time, and another had been severely beaten by the soldiers). However, the economic setback caused by the arrests, jailings, lawyers’ fees, and trips to Mazatlán. and the state capital has stripped it of all the limited resources and savings it had gradually accumulated since it moved to Lodasál a year and a half ago. Still, the members of the family are happy that they are all together again and—at least for the moment—free to proceed with their lives.

We celebrate the release of these campesinos and health workers who are our colleagues and friends, and would like to thank all the journalists, human rights activists, and concerned persons who rallied to help get Liberato out of jail.

Unfortunately, however, others will continue to be victimized as long as the Bush Administration persists in imposing its punitive, militarized approach to the drug problem. Last year US drug czar William Bennett openly said that “A massive wave of arrests is a top priority for the war on drugs.” Since he made that statement, arrests have escalated, not only in the US, but in Mexico and many other Latin American countries as well. Latin American governments know that the continued flow of critically needed foreign aid from the US and debt bailout funds from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank is contingent on their compliance with Washington’s mandate that they fight the war on drugs on its terms. Many if not most of the people arrested in this sham crackdown are innocent victims who, like Liberato, just happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

These abuses of human rights —in Mexico, other countries of Latin America, and here in the US as well—won’t end until the US public joins with people throughout the Americas to “just say `no” to a hypocritical, ineffective war on drugs which ignores the real causes of the drug problem while providing a handy pretext for strengthening the forces of repression both abroad and at home.

End Matter

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |