Captured by the Free Market: A Visit to the New Nicaragua

In November and December of 1991, Martín Reyes (from Projects Piaxtla and PROJIMO) and I went to Nicaragua to take part in three separate but connected events:

-

a large regional workshop on Child-to-Child activities,

-

a meeting of the Regional Committee for the Promotion of Community-based Health Care in Central America and Mexico, and

-

an international discussion group on Health Care in Societies in Transition.

While in Nicaragua, Martín and I also had a chance to visit a range of community initiatives. These included a neighborhood-run health program, a grassroots women’s organization, a family-run program for disabled children called Los Pipitos, two government centers for abandoned, abuse and disabled children, and programs serving the mushrooming population of street children.

Overall, we were impressed by the efforts of the Nicaraguan people to make the best of an extremely difficult situation. But we were distressed by the deterioration of living standards and public services that has resulted since the change in government in April 1990.

In the second article in this newsletter I will try to dive a tentative description of the current situation m Nicaragua, based on our observations. But first I would like to tell you about the Child-to-Child workshop, for it was an uplifting and heartwarming event.

Child-to-Child: A Challenge for Children, Health Workers, and Activists

About Child-to-Child

At its best, Child-to-Child is a hands-on learning adventure with empowering, even liberating possibilities. Begun in 1979 during the International Year of the Child, Child-to-Child activities have been introduced into more than 60 countries.

In disadvantaged communities, older brothers and sisters often spend more time caring for their younger siblings than do their parents, who often have to work long hours outside the home. So teaching older children to help with the food and health needs of the younger ones can make a big difference in terms of children’s well-being and survival.

The purpose of Child-to-Child, therefore, is to help school-age children learn more about the health, safety, and developmental needs of their ea younger brothers and sisters so that they themselves can take action in meeting those needs.

At its best, Child-to-Child is a hands-on learning adventure with empowering, even liberating possibilities.

Child-to-Child activities focus on a spectrum of problems and needs. For example, the `Diarrhea’ activity helps children learn how to prepare and give the sick child a special drink (oral rehydration therapy) to replace the liquid lost in watery stools. The activity `Making Sure Young Children Get Enough to Eat’ encourages older children to help make sure younger ones are fed energy-rich foods several times a day. It also stresses the importance of adding concentrated energy foods like vegetable oil to young children’s meals. Other activities cover such topics as accidents, hygiene, toy-making, and care of the teeth.

In Child-to-Child the methods are as important as the content. Children learn about meeting the needs of their younger brothers and sisters through a series of exciting, discovery-based activities. One of the tacit goals of Child-to-Child is to help transform—or, some might say, subvert—conventional education so that it becomes more relevant to children’s immediate needs and lives. At its best, Child-to-Child helps children (and teachers) develop a thoughtful, open-ended approach to problem-solving.

The challenge with Child-to-Child is to help the children make their own observations and draw their own conclusions rather than to just pour information into their heads like soup into empty pots. Because it equips children to better meet immediate needs in their families and communities, Child-to-Child can be a truly enabling process.

Unfortunately, as it has been introduced in many parts of the world, Child-to-Child has fallen short of its revolutionary goals. Too often the teaching becomes unimaginative and top-down, consisting merely of telling the children what to do and training them to parrot back `health messages’. They learn about instead of learning to.

Or, worse still, children are left out altogether. Many of the most touted and best-funded `workshops’ on Child-to-Child are conducted as a series of lectures by doctors, psychologists, and representatives from such organizations as UNICF with no children present. As a result, theory is emphasized to the complete exclusion of practice. Ironically, the Second World Congress on Child-to-Child was held at a luxurious conference center in Belaggio, Italy, where signs on the gate said “No Children Allowed.”

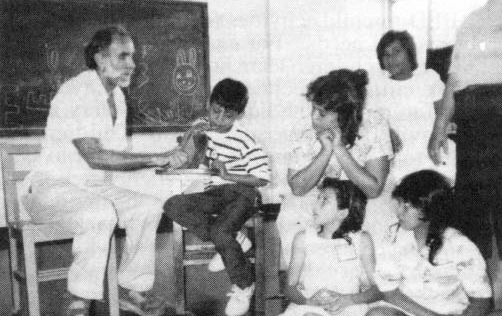

In contrast, when Martín Reyes helps to introduce Child-to-Child methodology, he always insists on the active participation of children.

Martín is a village health worker who now works with Project PROJIMO, a rehabilitation program run for and by disabled young people based in the tiny settlement of Ajoya, in western Mexico. Twenty-six years ago, when he was 14, Martín began working with Project Piaxtla, the community-run primary health care program based in the same village.

Martín has extensive experience with Child-to-Child. In the last several years he has gained international recognition as a gifted facilitator, and has helped various Child-to-Child programs get started. During 1991 Martín helped to initiate activities of this sort in Mexico (Oaxaca), Ecuador, and, most recently, in Nicaragua. Martín is emphatic that any seminar introducing the idea of Child-to-Child must center around activities with children themselves. “Learning-by-doing” is the key to a successful program.

The Managua Workshop

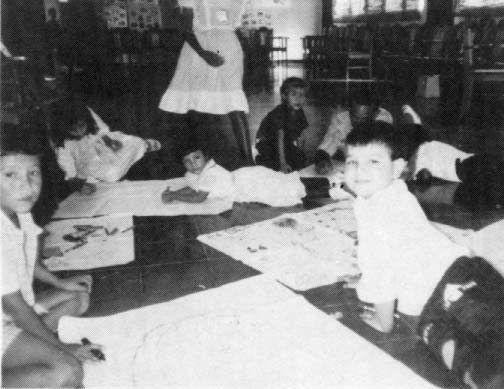

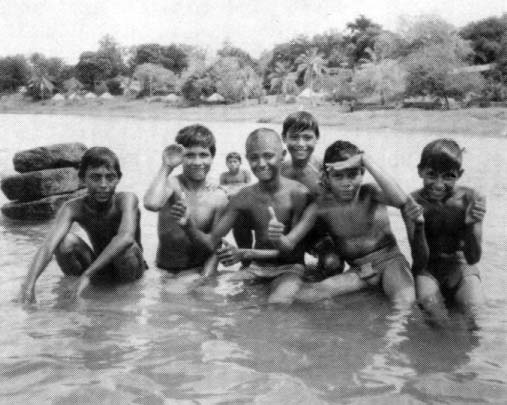

The Child-to-Child workshop in Managua was in many ways a great success. Of the 105 participants, 65 were children. Health workers and community activists from a range of settings came together, each bringing one or two children from their area. Some participants came from remote rural areas, others from the cities, and a few were street kids.

The most uplifting aspect of the event was the group dynamics, both among the children and between children and adults. At first, kids from different backgrounds were wary of each other. But in the course of the five-day workshop barriers collapsed; soon they all played and learned together with abandon. Also, barriers between kids and adults broke down, giving way to intergenerational play and a rich exchange of ideas. Through exploring Child-to-Child possibilities together, grownups and children gained an unusual level of respect and appreciation for one another.

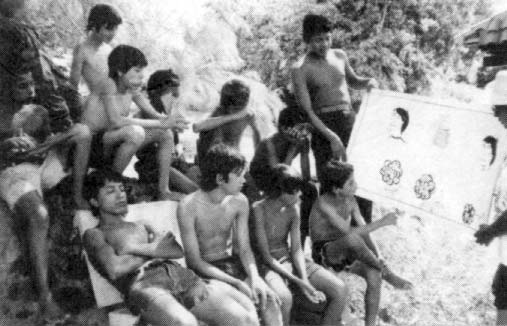

The workshop focused on child-centered activities in three main areas: community diagnosis, management of diarrhea, and disability.

The activity on disability was a real awareness raiser, mainly because of the enthusiastic participation of disabled persons themselves. Two physically disabled health promoters facilitated the exercises for sensitizing the group to the needs and possibilities of the disabled child. In addition, leaders from Los Pipitos, a nationwide organization of families of disabled children, brought along several disabled kids to participate and share experiences. All of the children marveled at the ability of a little blind girl to read from a bumpy sheet of paper with her fingertips (Braille) and asked her to teach them how to do it.

The disability activity included games for testing the hearing and sight of younger children. The value of these games was dramatically illustrated when the children discovered that two of their own group had moderate to severe hearing loss. The first was a little girl who never paid attention during discussions. No one had guessed why.

The other was a boy whose mother (also at the workshop) was distressed about his difficulty with speech. Doctors who had examined him had not detected a hearing loss and had diagnosed him as mentally retarded. Now, thanks to the children’s discovery that his problem may be related in part to deafness, the boy can be taken to an audiologist. Perhaps with a hearing aid his speech will improve. At a minimum, he will be given a seat in the front row at school so that he can hear the teacher more clearly. This could make the difference between his staying in school or dropping out.

A Child Who Overcame Terror: the Story of Darling

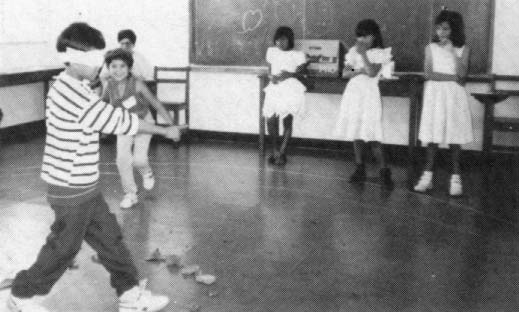

On the last day of the Child-to-Child workshop the children were divided into three groups and asked to present something they had learned, in the form of skits, stories, poetry, song, or in any other way they pleased. The group responsible for preparing the presentation on disability decided to put on a skit about testing vision in a classroom.

An amazingly capable, dynamic 15-year-old girl named Darling took the lead in organizing the children and planning the skit. She played the role of a mean, bossy teacher. The teacher was especially mean to a little boy, called Pedrito, who tried to hide in a back corner of the class. The teacher would write words on the blackboard and order Pedrito to read them. When the boy could not, she called him lazy, stupid, and worthless.

Then the teacher was called from the room by the principal. As soon as the teacher was gone, a boy m the class stood a and said, “I just got back from a Child-to-Child workshop in Managua. We learned to test each other’s eyesight and hearing. I think that maybe Pedrito doesn’t answer the teacher’s questions because he can’t see what she writes on the board.”

“Well, let’s test his vision!” said a girl. “Teach us how!”

So the boy pulled out of his pocket a folded paper with an `eye cart’ that the kids m the workshop had made the day before. The children proceeded to test each other’s vision. Sure enough, Pedrito proved to be near-sighted.

When the teacher came back into the room, the whole class stood up and confronted her. They explained that Pedrito had trouble seeing things at a distance and needed to sit up front, closer to the blackboard. “It’s not his fault that he can’t see well,” they told her, “so please stop scolding him!” The teacher apologized to Pedrito, asked him to sit up front, and promised to write in bigger letters on the blackboard.

After the children presented the skit at the final plenary gathering that afternoon, everyone applauded loudly.

Then Darling, who had played the teacher, raised her hands for silence. Speaking completely impromptu, she proceeded to sum up the larger meaning of the skit, and of Child-to-Child. Her words were so eloquent and full of conviction that everyone was riveted to what she said, which went something like this:

In too many of our schools, teachers pick on the kids who are slowest or weakest, or who need the most help. They scold them. They humiliate them. Then they flunk them. We children must stand up for those among us who are weaker or different, and defend their rights to dignity and respect. We must never again permit the strong to terrorize the weak!

In Child-to-Child we have learned many things. Above all, we have learned that those of us who are a little bigger or more able need to protect those who are smaller and weaker. Let us hope that we will remember this lesson when we grow up, so that we will join the struggle for a new society - one where the strong can no longer take advantage of the weak, and where we can all live in peace as equals.

Throughout the workshop, those of us facilitating had been impressed by Daring: her inner strength, her humanitarian vision, her leadership capacity . When we discussed who from the workshop might make the best `multipliers’ of the process, Darling’s name headed the list.

Not until the workshop was over did I learn the story of Darling’s past. She had grown up in a village which in the mid-1980s had been attacked by the Contras. At age eight, she had watched as her family was tortured and killed, and then she had been sexually abused.

For weeks afterwards Darling had been in shock, unable even to speak. But she was placed with persons who gave her the love and understanding she needed to gradually rediscover herself and find the courage to move forward with life. In the long run, it seems that Darling is a stronger and wiser person for what she has lived through - that, somehow, her suffering has given rise to strength.

In the wake of abandonment there needs to be reconciliation: hands that reach out to shelter and empower.

Darling’s transformation is not unique. Years ago in Mexico, at a gathering of leaders of community initiatives struggling for people’s health and rights, we tried to pinpoint some common thread of experience that haled us on our unusual paths. Our backgrounds were very diverse. The only thing we all seemed to have in common was a strong sense of abandonment in early childhood.

This is not to say that all abandoned children become committed leaders in the struggle for change. In the wake of abandonment there needs to be reconciliation: hands that reach out to shelter and empower. Under the Sandinistas, whatever their flaws, there were humane social structures that did their best to nurture and provide for children who had become victims of the war, economic hard times, or other social problems.

Causes of Ill Health - Through the Eyes of a Street Child

Early in the workshop, in order to help the youngsters think about the health needs in their homes and communities, we asked each child to draw a picture on a large sheet of paper of something related to his or her own life and experience. Most drew pictures of a house with flowers around it, and called it “their home.” But one little boy named Juan Carlos drew a church.

Next we asked the children to add to their drawings something that related either to good or bad health. Most drew such things as protected or unprotected wells, children shitting on the ground or in latrines, and so on. But Juan Carlos drew a police car in front of his church with four human figures around it. Red lines extended from the top of the police car, indicating that its light was flashing. When asked to explain his picture, Juan Carlos pointed to a small human figure with a bag in its hand. “This boy stole something from that man,” he said. And, pointing to the guns in the hands of two other figures, he added, “These policemen are shooting at the boy.”

Juan Carlos is a street child. Every night, when the other kids at the workshop went to bed, Juan Carlos would slip out and return to the streets of the inner city. When confronted about this, the boy explained (and the street educator who had brought him confirmed) that at night he returned to the street to look after a still younger homeless child. The younger boy, he said, would feel abandoned if he didn’t return to spend the night with him.

It occurred to us that this 11-year-old street boy, small for his age and with a speech impediment, was truly living Child-to-Child while the rest of us were just playing at it. During the closing ceremony of the workshop, Juan Carlos was applauded as a role model for the other children, and was resented with a set of colored marking pens. He was so delighted that he wept.

Still, when the workshop came to an end, Juan Carlos returned to the streets. His life will not be easy or secure. His shocking drawing of ‘events affecting health’ from a street kid’s point of view gave us insight into the severity of the risks that he and others like him now face.

The High Cost to Children of Nicaragua’s Change in Government

Juan Carlos is but one of the fast-growing number of destitute, homeless children who have appeared on the streets of Managua since the election of the UNO government.

These children are part of the collateral damage inflicted by US destabilization tactics and low-intensity conflict. Washington’s relentless pressure wore down the Nicaraguan people to the point that a majority of them voted for the conservative opposition coalition UNO (the United Nicaraguan Opposition) in the February 1990 elections. As long as the Sandinista administration was in office, its wide range of social programs - especially those safeguarding the health and needs of children - kept the numbers of street kids to a minimum.

With the change in government, however, the economic situation has become even more desperate, giving rise to escalating social problems, and the safety net protecting the poor has disintegrated. As real wages decline and more and more families find themselves without work, social programs and subsidies - which are needed more than ever - have been severely cut or completely eliminated.

Pressure from the North for a free market economy and privatization of government services has played a major part in Nicaragua’s current crisis. As a condition for loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the UNO government agreed to slash funding for all public services and welfare programs by an average of 50%. As a result, many thousands of people lost their jobs. The few social programs that remain - now running with half their former staff and budget - must try to meet the needs of the swelling ranks of destitute people. No wonder the remaining public services are overburdened and ineffective! The situation is reminiscent of that in the US during the Reagan years, but several orders of magnitude more serious.

The IMF and USAID have also pressured the UNO government to freeze wages and free prices. Last August the government announced that the minimum wage would be set at the equivalent of $30 a month in the countryside and $46 a month in the cities. Labor unions protested, noting that the `market basket’ needed to meet a family’s basic needs costs roughly $130 a month. Even arch-conservative Cardinal Obando y Bravo has called the government’s new wage scale “starvation salaries.”

Unemployment and underemployment in Nicaragua have risen to over 60%. With the recent major cutbacks in government services and spending, thousands have lost their jobs.

The impact of slashing government budgets has been exacerbated because the reduced funds available go into fewer pockets. While Sandinista government officials generally earned about $200 a month, today many UNO bureaucrats earn from $12,000 to 15,000 monthly. Paying such high salaries significantly widens the gulf between rich and poor and further reduces the money left over for public services.

80% of the prostitutes, many of them teenagers, have begun their trade only within the past year.

Added to all this is a huge increase in corruption, which has further compromised all services, including health. Today, even more than under the Sandinistas, community clinics (those which have not yet been closed) often lack basic medicines. So even the poorest patients are sent to commercial pharmacies, where drugs are outrageously overpriced. This medicine shortage could have been at least partially avoided. To help meet the country’s dire need for essential drugs, the Swedish government has been providing Nicaragua with over one million dollars worth of free medicines annually. But the latest shipments of these medicines have been held up by the Customs Department. It seems some high UNO officials have investments in the pharmaceutical industry. To keep prices and sales of commercial medicines high, they have blocked importation of the donated drugs. Some of these drugs, impounded for nearly a year, have now expired. Frustrated by this corrupt behavior, the Swedish government discontinued its medicine donations at the end of 1991. (There were also obstacles to the distribution of donated medicines during the period of Sandinista rule, but they were surmountable and were primarily due to red tape and lack of trained personnel, rather than corruption.)

More Prostitutes and More Big Cars

The economic crisis, soaring unemployment, and cutbacks in public services have taken a heavy toll on Nicaraguan society. Diseases such as polio and measles, which had been reduced or eliminated under the Sandinistas, are making a comeback. Malnutrition rates in children have increased alarmingly. School enrollment has dropped.

As hunger and homelessness grow, not only are there more street children, but prostitution—which had been reduced to low levels by the Sandinista government after being rampant during the Somoza dictatorship—has proliferated. A neighborhood women’s league we visited, which is struggling to protect women’s rights, recently surveyed hundreds of Managua’s prostitutes. Their November 1991 study found that 80% of the prostitutes, many of them teenagers, have begun their trade only within the past year. They sell their bodies to feed their children, or their younger brothers and sisters.

Diseases such as polio and measles are making a comeback.

Who has the money to pay for commercial sex? Lots of people: the new, highly paid bureaucrats, the owners of some of the new private businesses launched with aid from the US, some of the ex-Contras, and businessmen and former big landowners newly returned from self-imposed exile in Miami and elsewhere. Sexual tourism in Nicaragua is also reportedly on the rise.

One of the provisions of the pact that Sandinista leaders have negotiated with the Chamorro Administration is an agreement to allow returning Nicaraguans to bring all kinds of goods, including automobiles, back into the country duty free. This has caused social and environmental headaches. With the influx of cars and trucks, traffic in and around Managua has become a nightmare, and air pollution is becoming a serious problem.

How rapidly the contrast between squalor and affluence, with all the resulting social degradation, has again become a part of the Nicaraguan landscape!

More Drug Trafficking and Drug Use

Another growing problem in post-Sandinista Nicaragua is the escalating trafficking and use of hard drugs, especially cocaine. Under the Sandinistas, illicit drug use—which had been widespread during the last years of Somoza rule—was minimal. However, starting in 1984 when the US Congress passed the Boland Amendment outlawing military aid to the Contras, the CIA helped the latter carry out a covert arms-for-drugs trade. Now these same Contras have returned to Nicaragua. For this and other reasons, including the worsening economic situation, substance abuse has increased dramatically since the change in government. As elsewhere, the uncritical, indiscriminate embrace of the free market, combined with poverty and despair, has had the effect of invigorating the multinational narcotics industry, both legal and illegal.

Two Government Child Centers

Thanks to a friend we made in Managua, we had a chance to see, first hand, the impact of ‘structural adjustment’ (IMF-imposed austerity policies) on services for children at high risk. Eduardo Carson, a Canadian specialist in child disability and development, has been working in Nicaragua for ten years. Having used our book Disabled Village Children, he wanted to meet us. So he invited us to visit the two ‘Centros de Protección Para Menores’ (Centers for the Protection of Minors) where he works.

These are government-run centers for orphaned, abandoned, abused, and/or disabled children, located on the outskirts of Managua. The ‘Niños Mártires por la Paz’ (‘Child Martyrs for Peace’) center is for children seven years old and younger. The Rolando Carrazco center is for children from eight years on up.

Started by the Sandinistas in the early 1980s, the centers were set up as provisional group homes. Children stay here under the care of ‘house mothers’ until they can be placed with families in the community. Priority is given to returning the child to his or her own parents or relatives. When this is not possible, adoptive parents are actively sought. Under the Sandinistas this was done through a process of community outreach and awareness-raising. Many families gladly adopted abandoned or orphaned children out of a sense of solidarity, even though they received no economic assistance (except when the child was disabled).

Now it is much harder to place children, both because the economic situation is even worse than during the period of Sandinista rule and because the present government lacks the Sandinistas’ strong popular roots.

Also, the number of abandoned kids has risen sharply. Many poverty-stricken couples or single mothers simply can’t find a way to feed their children. So, out of desperation, when a baby gets sick they take it to a hospital under a false name and address, and never return. At the Rolando Carrazco center we met four young siblings whose mother, unable to feed them, had shut them into her apartment and vanished.

The child protection centers accept and then try to place as many children as they can. But they can’t begin to keep up with the present epidemic of homeless and abandoned children.

On our arrival at the Niños Mártires center, Eduardo took us to a large fenced-in yard.

“I want you to meet our child psychologists,” he said, “the only ones whom our new kids will speak to when they’re too terrified to talk to any of us.”

He pointed to the animals in the yard: several ducks and geese, an old donkey, and a tame deer.

“When many of the children come here, they are in emotional shock,” he explained. “Some have seen Contras torture and massacre their mothers and fathers. Some have been forced by the Contras to set fire to their homes with their brothers and sisters still inside. Some have been tortured or gang-raped. You wouldn’t believe what they’ve been through. (Eduardo was referring here to victims of the Contra war of the 1980s.)

“At first, they won’t talk. They keep it all inside. They have lost all trust in the world of adults, in human beings. No one can reach them - no one except the animals.

“So we bring them out here. And before long the geese are feeding from their hands and the doe is licking their cheeks. They begin to talk to the animas, to tell them things they dared not tell anyone, terrible experiences that they had blocked even from their own minds - except in their nightmares.

“First they open up to the animals. Then, little by little, they open up to us.

“But everything is harder now than it used to be,” he continued. “Often we can’t afford food for the animals. Our monkey died. And deer.” a few weeks ago someone stole one of our pet deer.”

“Why would anybody do that?” we asked.

“To feed their children,” replied Eduardo. “Remember, lots of people are starving.”

Our Canadian friend was heartbroken about the way that the new government policies have compromised the two centers. Not only have money and staff been cut by half, but most of the original highly competent and dedicated staff, mainly Sandinistas, have been replaced by friends and relatives of UNO officials. Many of the new staff lack the skills, patience, or commitment to work with children with special needs.

Our friend pointed to a man stoically working in the garden, while a group of disabled children looked on. “Our old staff helped the children to do the gardening themselves,” he said. “And the kids loved it! The flowers had meaning!”

Eduardo explained to us that much of the simple, imaginative equipment in the center’s playground had been modeled after our ‘playground for all children’ at PROJIMO. It was indeed a splendid playground. But we noticed that many of the playthings were now broken. Clearly the centers have seen better times.

Still, both centers convey the inspiration and vision of their founders. Their outer walls are flamboyantly decked with delightful murals. On the outer wall of the Centro Rolando Carrazco is a grand figure of “Mother Nicaragua,” her windswept hair streaming protectively over a ten-meter long panorama of disabled and non-disabled children playing, working, and studying together.

Oddly, Mother Nicaragua’s flag-like hair is painted in two long bands of yellow and black. We earned that her hair used to be red and black, representing the Sandinista flag. But to prevent defacement of the mural when UNO took power, the Sandinistas painted over the red band of hair with yellow to disguise it. (Nearly all murals identified as ‘Sandinista’ were obliterated when UNO took over.)

What is unique about most of these murals at the child protection centers is that the children helped paint them. They all sport the children’s signatures, in the form of a brightly colored hand- or footprint beneath each child’s name.

Our friend explained that desecration of these lively murals had begun while the FSLN (Sandinista Front for National Liberation) was still in power. Indeed, when the mural on the adobe wall surrounding the Niños Mártires center was first painted six years ago, local village children began to vandalize it, scrawling obscene graffiti over the paintings.

To cope with this problem, the teachers at the center, instead of seeking punishment of the village children, invited them to help repaint the mural they had vandalized. So village kids joined disabled kids in creating a new mural. Each child added his or her hand- or footprint and name. This put an end to the vandalism. Indeed, this mural is one of the few in Managua that was not destroyed either by UNO supporters or Sandinistas during the tense period following the 1990 elections.

But why did the village children vandalize the mural in the first lace? The answer is complex, and can be traced to the pervasive destabilization tactics of low-intensity conflict.

The Niños Mártires center is located in a very poor, semi-rural area on the outskirts of Managua. The site was once one of the Somoza family’s resorts. After the Somoza dynasty’s overthrow, the Sandinistas converted it into the child protection center. At first the center was well-accepted. But as the US government’s campaign against the Sandinistas escalated, it ran into problems with the local community.

Like many of the poorest communities near Managua, the neighborhood surrounding the Niños Mártires center was visited during the 1980s by right-wing evangelists. Many of the reactionary evangelist groups that flooded into Nicaragua at this time were financed by US government agencies or US-based private conservative organizations, and had a covert political agenda. They put the fear of the Red Plague into the local people, portraying the Sandinistas as the devil incarnate.

Because the children’s center was run by Sandinistas, it was fair game for attack. When disabled children painted its wall, the preachers denounced this too as sinful, charging that the Sandinistas were wasting paint on useless murals while the villagers were too poor to paint their doorposts. Many residents viewed the vandalism by the village children, not as misbehavior, but as a righteous act of war - a war which the children and their families had been duped into fighting on the wrong side and for the wrong reasons.

Fortunately, when the little vandals were invited to join in repainting the mural, they were able to see through the lies they had been fed and make peace.

If only we adults could see as clearly and learn as quickly as children!

Managua’s Street Children

One of the best indicators of a population’s overall health is said to be infant mortality. But if we want to look at health in the broader sense of a whole community’s “complete physical, mental, and social well-being” (the World Health Organization’s definition of the term), other indicators are also needed.

One indicator of a society’s health, now being used by UNICEF, is the ratio in annual earnings between the richest and poorest 20% of the population. According to this `fairness factor’, the systemic health of Nicaragua—as well as that of the United States and indeed nearly every country worldwide has been on an ominous downhill course during the last few years.

Another base line indicator of `community health’ might be the relative number of homeless people, especially street children. On this count, too, Nicaragua -again along with the US and most other countries - has recently taken a sharp turn for the worse:

-

In Nicaragua, UNICEF reports (in December 1991) that there are now at least 17,000 street children—many more than at any time during the tenure of the Sandinista government.

-

In the United States, Covenant House (an organization that runs shelters for homeless young people) estimates that at least one million children regularly sleep on the streets. And the number is rapidly rising.

According to a wide range of indicators, it seems that the peace and prosperity Nicaraguans dreamed of when they voted for UNO have turned out to be a bitter illusion.

Our Canadian friend, Eduardo, works with one of several non-government organizations that have stepped into the welfare gap left by the change in government. One of them is a very informal program that tries to improve the situation of street children.

One afternoon Eduardo took us to a hangout of street kids in the old city center of Managua, which has remained in ruins ever since it was leveled by the devastating 1972 earthquake. Scores of youngsters live among the rubble of old buildings and warehouses. Some of them shine shoes, earn a pittance for watching (that is, for not vandalizing) parked cars, beg, steal, run errands, and in other ways try to scrape together enough to survive on. Every morning a bevy of boys picks through the fresh garbage at the city dump, searching for small prizes to eat or sell.

Eduardo obviously has good rapport with the street kids, who swarmed around his pickup as we pulled up to the remains of a large cement building. The kids led us into the shadowy entrails of the wrecked edifice.

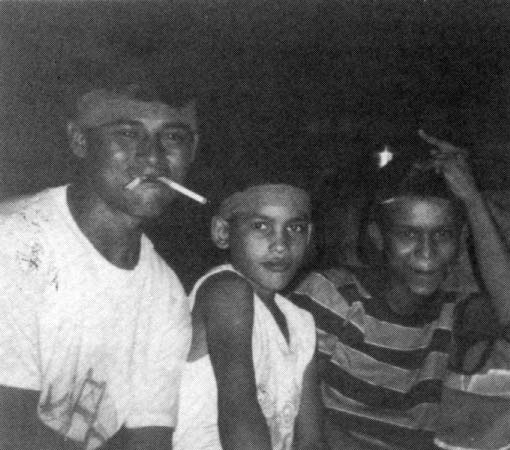

The street kids ranged from about nine to thirteen years old, a few of them older. All the members of this particular gang were boys. The younger ones seemed fearless of us strangers, and knew how to dull on our heartstrings. But some of the older boys initially kept their distance, eyeing us with a mix of suspicion and hostility. Gradually they warmed up.

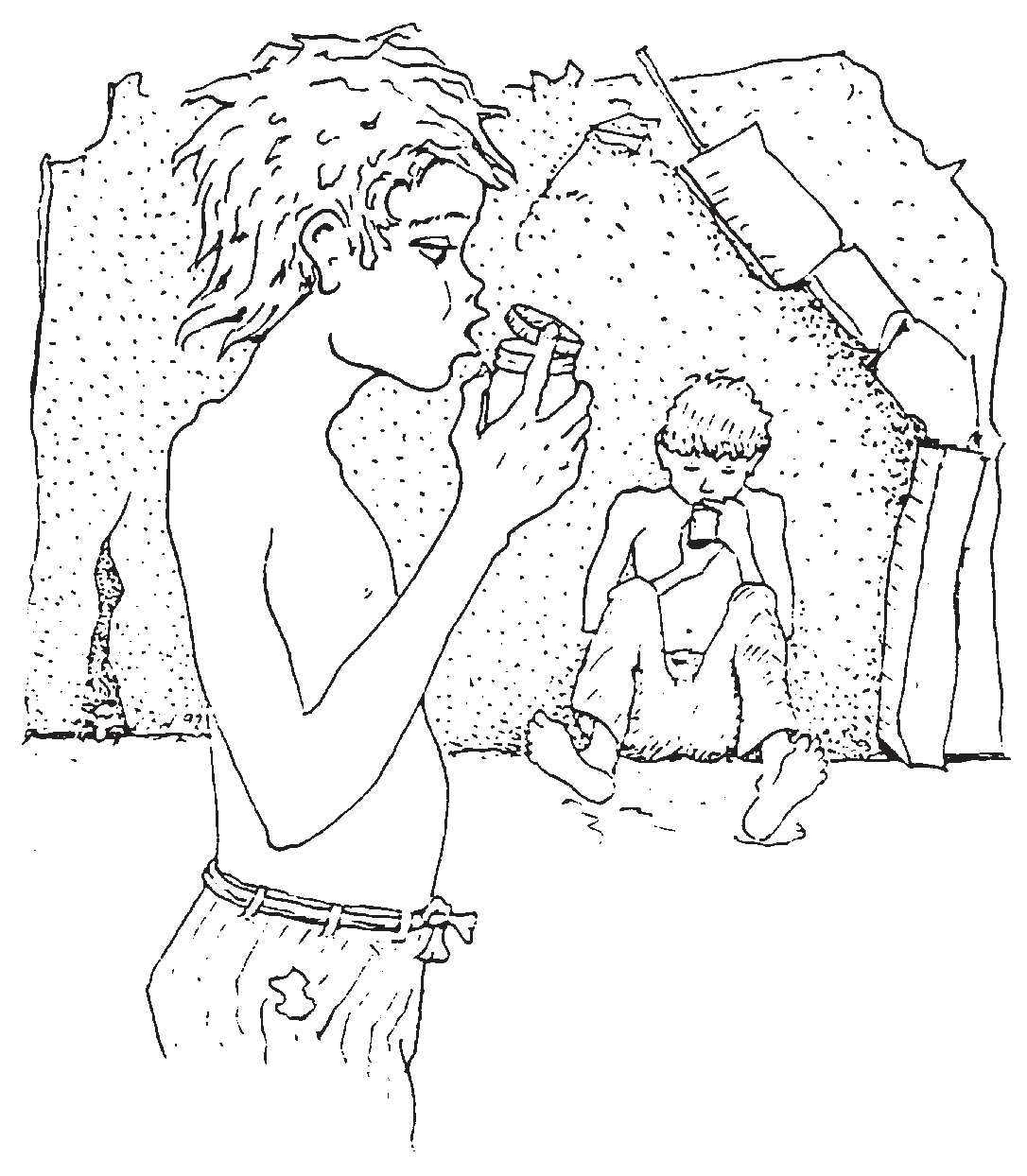

Eduardo had been reluctant to bring us after midday because, he said, the kids would be high on glue. He was right. Each boy earned on him a small bottle, like a Gerber baby food jar, filled with shoemaker’s cement. Every minute or so, as we talked, the children would put the bottles to their lips, lift the lids slightly, and inhale.

The kids seemed drunk. Their eyes were glazed, their speech somewhat slurred, and their movements a bit off balance. The boys were all extremely thin, which gave the younger ones a deep-eyed, hauntingly angelic look. When we asked one boy, about ten years old, why he sniffed glue, he shrugged and said it was just something to do, then added, “Se quita el hambre.” (It takes away hunger.)

Most of these kids have been repeatedly beaten by the police. (Some had scars to prove it.) Sometimes they are beaten because they have committed (or are suspected of committing) - petty crimes. But more often they are beaten because they are there: a problem that warrants correction. Since Nicaragua’s Constitution prohibits jailing children under 16, policemen routinely resort to physical punishment, often quite brutal. They sometimes raid the hangout, sending the ever-vigilant kids scampering up jagged walls and across roofs.

We learned that within a gang of street kids there is relatively little violence. Some of the older boys bully the younger ones. But just as commonly, older boys defend and take care of the younger ones, with whom they often have sex.

Although there are reportedly also a lot of girls who live on the streets, they tend to frequent more prosperous areas. The girls, we learned, are mostly thirteen to fourteen dears old or more. They survive by selling their bodies, mostly to older clients.

As for the street kids in the inner city, Eduardo is still trying to get to know them and figure out how best to help them. As yet there is no organized program that addresses these children’s needs.

Eduardo feels that the biggest immediate danger the kids face is glue-sniffing. It damages their brains and weakens their lungs.

But the problem is not easy to combat. Marketing shoe cement to children has become a lucrative business. Nicaragua apparently imports large amounts of this cement - many times what is needed for shoe repair. The cement is imported through a multinational supplier. Shopkeepers in depressed communities do a thriving business with weekly refills of the children’s little bottles. Health activists suggest that restrictions be placed on the import and distribution of shoe cement. But it is unlikely that such a law will be passed in the present climate of unrestricted free trade.

So what can be done? Telling the kids that glue sniffing is dangerous to their health doesn’t impress them, and disciplinary measures would be counterproductive.

Eduardo has come up with one modest way to alleviate the problem. The kids love to go for rides in his pickup. Twenty or more of them scramble in at once. When he has time, he takes them for outings to swim in a nearby lake or to climb the Masaya volcano.

But in order to be allowed to go on these outings, the kids must agree to leave their glue behind. To begin an outing, the kids themselves had the idea of a ‘glue bottle smash’, which they have turned into a sort of pagan rite. They stand high on the cab of the truck and, whooping loudly, fling their glue bottles against the pavement.

When he takes them to the volcano, Eduardo has the boys run a footrace to the top of the final hill. Although the climb is neither long nor steep, it is exhausting for many of the long-term glue sniffers and cigarette smokers. Upon reaching the toy, everyone wins a prize (something to eat). But it is understood that no one will receive a prize until every child makes it to the top. In this way, those who are fastest, instead of running ahead, learn to help the slower kids along. This makes the race a cooperative challenge rather than a competitive one.

When they reach the top, all the kids are laughing and coughing and breathing hard. Eduardo feels that these outings, while they have not yet convinced any boys to give up glue sniffing, do give them a day’s respite and a chance to clean out their lungs. The excursions also provide the kids with a breath of fresh air for their minds and spirits.

Following our visit to the inner city, Eduardo took us to an asentamiento (new settlement) to see a small community center set up for street kids. The center -which the children painted themselves - serves as a place for both play and informal study. When folded upright, the ping-pong table becomes a blackboard. A `street educator’ teaches basic literacy so that kids who want to can get into public school and hold their own. A few of the kids have begun to go to school.

The children do not sleep at the center, but they can bathe there and come and go as they please. The only strict rule is no drug use inside the center. Glue, drugs, and cigarettes are deposited on entry and picked up on the way out. At present the center serves only boys, but there are plans to include girls.

Several similar centers exist in Managua. But together they serve only a tiny portion of the growing numbers of street kids. Only through a return to a more equitable social order which assures that all citizens’ basic needs are met can the problems of street children and child prostitution be meaningfully resolved.

Where is Nicaragua Headed?

Nicaragua is locked in a steadily worsening spiral of social and economic crisis. Its adoption of structural adjustment and free market policies has not led to economic recovery. Rather, it has produced further economic stagnation, widened the gap between rich and poor, and driven millions of marginalized citizens into extreme poverty.

In the February 1990 elections, many Nicaraguans voted for the UNO party at least in part because they realized that, if they voted for the Sandinistas, the US-sponsored war (with the accompanying unpopular draft), terrorism, and economic sanctions would continue. The Bush Administration, like its predecessor, made it very clear that it would simply not accept a Sandinista victory at the polls, and would never let the FSLN govern in peace.

But the situation has not improved with the change in government. (The one exception is the fact that the Contra war has ended, but the peace process had already been all but concluded by the Sandinistas, and the peace has proved a fragile one, with some Contras and Sandinista partisans once more taking up arms and doing battle.) The US has failed to deliver on many of the promises of aid it dangled before the Nicaraguan people to entice them to vote for UNO. And most of the aid that has materialized has been used to reintegrate the Contras, provide start-up funds for business, and privatize public services. In short, as is so often the case, the aid has benefited a small minority at the expense of the majority.

In sum, in Nicaragua, as in so many other poor countries, austerity measures imposed by the IMF and USAID have caused increased misery. As local currency devaluates, prices rise faster than wages. This further reduces the buying power of families already on the margin. Rates of child malnutrition and infant mortality have begun to rise again after their dramatic drop during the early years of the Sandinistas. Diseases of poverty which had been virtually eliminated are again on the increase.

All in all, it is a sorry situation for a country which, in the early years of the Sandinistas, was praised by the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization for its remarkable progress in bettering its people’s health.

Actually, `sorry’ is not the right word. Many Nicaraguans are angry. Many people who sharply (and in some respects rightly) criticized the Sandinistas in the late 80s are beginning to weigh their losses against their gains.

My impression is that there is still hope for revival of the people’s struggle in Nicaragua. In the 1970s Nicaraguans came together to fight for liberation from the Somoza dictatorship. Then, during their ten and a half years of self-determination under the Sandinista government, they mobilized to achieve literacy, health, and economic development. The Revolution brought about a popular awakening and a taste for freedom which are proving hard to destroy.

During our visit to Nicaragua we became convinced that the Revolution is still alive. Many of the people in the women’s organizations and community health programs (now run outside of government) showed a remarkable vitality and commitment to the struggle for people’s health and rights. In fact, now that they can no longer rely on the government for support and direction, they have in some cases gained a healthy measure of self-reliance and autonomy which they did not always enjoy under Sandinista rule. And, conversely, the Sandinistas, now that they are being forced to “govern from below,” are being forced to renew their links to ordinary Nicaraguans, especially the poor, and to turn once more to the grassroots activism that made the Revolution possible in the first place. But this resurgence of grassroots dynamism can only fight a holding action in the absence of remotely adequate funds and resources.

Nicaragua has stronger, more active organizations of disabled people than any other country in Latin America. Even the children we met seemed to reflect something of the revolutionary spirit.

In the Child-to-Child workshop we were struck by the difference between the Nicaraguan children and groups of children we have worked with in other countries, especially Mexico. The Nicaraguan children impressed us as being more open, more self-assured, more ready than most other children to stand up, speak out, and express their ideas. The germ of liberation is still in their blood.

And yet, for all their dynamism, Nicaraguans working at the community level can at best fight a holding action as long as they lack adequate resources.

There is little doubt in my mind that, if the US government would only allow them a free hand, the people of Nicaragua would soon forge a healthier and more equitable society. Nicaragua could once again become a model of people-centered development for the rest of the Third World - perhaps an even better one, with some of the kinks ironed out and the pressure imposed by the superpower to the north removed.

We must all do whatever we can, in our own way, to enable the people of Nicaragua-and of all the rest of the world, especially the developing world - to regain their right to self-determination.

Situation Desperate and Getting Worse: An Update on Events in Nicaragua

Up until last year, I had always felt safe walking the streets of Managua. Now, the stark contrast between the very rich and the nearly starving is shocking. Barefoot children go door to door begging for salt, and crime is common. It’s not just foreigners who are targeted; the poor also steal from each other. The child care center where I worked had to hire a full-time guard to prevent theft of supplies, kitchen utensils, and even the fruit from the trees we planted in the playground. Employment of guards is increasingly common, not only among urban businesses, but in rural areas as well.

Last March, during a conversation with a friend in the countryside, I began to better understand the effects of poverty on an entire society. My friend told me about hunger, about having no meat, few vegetables, and often having no milk for his baby daughter. Every day his family ate rice and beans, which could be purchased at the store. (Now poor families have only tortillas.) My friend had considered raising chickens. He had time and ample space, and chickens require little food. He also thought of planting vegetables. He did neither, though, because he knew that the chickens would be stolen and the vegetables would be harvested by thieves (or hungry neighbors) even before they had a chance to ripen. I suspected that this kind of hopelessness carried over to many businesses as well. I was struck with just how disempowering poverty is, and how it creates a vicious cycle. People don’t dare invest in the future, the economy’s free fall accelerates, and the national standard of living sinks lower and lower.

In 1980, the Sandinista government set up and subsidized child development centers (Centros de Desarrollo Infantil, or CDIS) in neighborhoods all over the country. Remaining in operation for the next ten years, the CDIs quickly became one of the Sandinistas’ most successful social programs. The Ministries of Health (MINSA) and Social Security (INSSBI) trained women to care for children ranging from 40 days to six years old. Besides providing employment and education for many women and parenting help for neighborhood families, the CDIs greatly improved the nutrition of many poor children. The centers served a daily meal, along with several nutritious snacks. A nurse was always in attendance, and the children received health checkups from a pediatrician who visited weekly.

The teachers were kind and attentive, so the children received excellent care and some educational stimulation. The latter is especially important, since many Nicaraguan parents have never had access to formal education. Many households don’t even have books, which are of little use when many people are illiterate. This was the case in Nicaragua before the Sandinista government’s ambitious 1980 literacy campaign in which high school and college students and others were trained, provided with simple reading materials, and sent throughout the country to teach people basic reading and writing skills. The campaign succeeded in reducing the national rate of illiteracy from 50% to 13%.

In February 1988, a nutritionist colleague and I worked as volunteers in one of these CDIs. Called CDI Colombia, it was located in the Don Bosco neighborhood of Managua. We facilitated workshops in preventive health care and nutrition for the staff and parents. In the process, we made some lasting friendships. Early in 1989, at a time when Hurricane Joan had just devastated much of Nicaragua and the economy was reeling from the effects of the US trade embargo and Contra terrorism, we received urgent appeals from CDI Colombia. INSSBI had just announced that drastic cuts would have to be made in food subsidies to CDIs, largely because more funds were needed for defense.

We did fundraising in the US for food and educational materials. The combined aid from our support group, the Swedish and Spanish governments, and some other international solidarity groups helped CDI Colombia continue providing high quality child care. Thanks to the increased cooperation of neighborhood parents and the hard work of the staff and director, CDI Colombia even became a model for other centers.

In March 19911 met with CDI Colombia’s director to begin planning some income-generating projects which could be run by residents of Don Bosco to provide local support for their child care center. Nothing came of these plans, however, because shortly afterwards the director was replaced. She was dismissed, not for incompetence, but because she is a Sandinista. She is not the only one to meet this fate: ever since the 1990 elections, Sandinistas holding government positions all over Nicaragua have been “getting the broom.”

From May 1989, when we formed our support group, until the Chamorro Administration assumed office in April 1990, we supported CDI Colombia by sending funds to INSSBI; that ministry then passed them on to CDI Colombia’s director, who sent the money on food for the children. When the united Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO, the conservative coalition that won the February 1990 national elections) took over, we no longer felt confident that funds provided to INSSBI would actually reach the children. I learned from AMNLAE, Nicaragua’s leading women’s organization, that INSSBI had misappropriated funs earmarked for some CDIs AMNLAE supported. Moreover, we felt that we could not support many of the Chamorro Administration’s policies, such as erasing the history of the past ten years from school textbooks and privatizing schools, health care, and child care, thus effectively ending subsidies for public programs serving poor children.

As a result, we began bypassing INSSBI and channeling funds directly to MI Colombia’s director. In May 1991 INSSBI barred us from making further direct contributions to CDI Colombia. We responded by severing our relationship with both INSSBI and CDI Colombia and switching our support to two other CDIs run by community organizations in very poor neighborhoods.

When the Sandinista labor unions objected strongly to UNO’s “broom” policy, the government backed off. In the early summer of 1991 it announced a new initiative ostensibly designed to reduce government spending and inflation. The policy, euphemistically dubbed the “Occupational Conversion Plan” and funded by the US Agency for International Development, consists of offering a lump sum of $2,000 (in US currency) to government employees who quit their jobs and sign a pledge that they will not take another government job for four years. This is a lot of money by Nicaraguan standards, and many employees are succumbing to the temptation, often using the money to go into business as vendors of pastries, fruit drinks, cheap imported goods, or in other similar ventures. Unfortunately, the informal sector of the economy where such activity takes place is already saturated, the money is spent quickly, especially with the rising cost of living, and many people who have taken this route find themselves broke and with no viable way to make a living. Besides getting rid of Sandinista government workers and slashing the public payroll, the policy is also intended to reinforce the growing trend toward privatization. It has taken its greatest toll, not on bureaucrats, but on badly needed first-line service personnel. The plan has forced a number of hospitals, health posts, CDIs, schools, and state business enterprises to shut down for lack of staffing.

While causing painful dislocations in all sectors, the loss of workers is especially grave in the health field. At a time when a cholera epidemic is looming on the horizon, those public hospitals that remain open are dangerously short on personnel. Our visit in March coincided with a strike by health workers. It is a sign of just how desperate economic conditions have become that this strike was started by a small group of private physicians who protested that their pay was too low to live on. (They were making about $220 a month.) To the doctors surprise, they were immediately joined by the entire health workers union, which complained that its members could not maintain sufficient stamina to care for patients on the amount of food their salaries could purchase, and that the stocks of medical supplies and medicines they had to work with were grossly inadequate. The strikers “won” a small salary increase which was quickly dissipated by inflation and the general devaluation of the nation’s currency.

Meanwhile, the social gains made by the Sandinistas continue to be eroded. The nationwide vaccination campaign functions only sporadically because of government disorganization. The incidence of respiratory infection has increased among children, and more than 650 children died in the 1990 measles epidemic. The number of cases of dengue and malaria is expected to rise dramatically now that public health measures to control the mosquitoes that transmit these diseases have been all but abandoned. Deaths from severe malnutrition and from dehydration caused by diarrhea occur regularly. The Health Ministry estimates that 84% of the rural population has no access to toilets or latrines. A recent United Nations development project report found that 54% of Managua’s residents live in overcrowded conditions of extreme poverty without water, electricity, education, or health services. Just since January 1990, 15% of Managua’s population has been forced to move into squatter settlements. The government evicted some families from homes for which they didn’t hold legal titles; others simply didn’t make enough money to pay the $500 monthly rent.

Deaths from severe malnutrition and from dehydration caused by diarrhea occur regularly.

Shortly after taking office the Chamorro Administration moved to privatize the education system. Since that time, 200,000 children have had to drop out of school. One-third of the country’s college students are currently unable to continue their studies. It costs only $1.00 per month to send a child to elementary school and $2.00 to send one to high school, but the average salary is $50 a month. Books and school supplies that used to be free must now be bought by children’s families.

Although the US news media have turned their attention elsewhere, we would be dangerously mistaken to believe that the US government is through intervening in Nicaragua - or that the suffering of the Nicaraguan people has come to an end. Not satisfied with having killed 40,000 Nicaraguans by illegally funding ten years of Contra terrorism and having helped to devastate the country’s economy by imposing a trade embargo and credit boycott, Washington continues to meddle in this small nation’s internal affairs.

The Bush Administration interfered in the February 1990 national elections by making large contributions to UNO’s campaign, holding out the prospect of an end to US support for the Contras, the dropping of economic sanctions, and an economic aid package if UNO won, and rebuffing all Sandinista overtures for a cessation of hostilities in the event of a Sandinista victory. Coming against the backdrop of war, economic crisis, and severe, prolonged hardships, this US intervention helped tip the scales, contributing to the Sandinistas’ surprise defeat.

When President Chamorro announced her relatively conciliatory stance toward the Sandinistas, she made enemies in Washington. By threatening to withhold future aid to Nicaragua, the Bush Administration coerced the Chamorro government into dropping Nicaragua’s request that the World Court ask the US to pay it war reparations (in 1984 the Court ruled in Nicaragua’s favor on a suit filed by the Sandinista government against Washington to end US military aggression). But the UNO Administration has not completely succumbed to US control. Despite the fact that her government is committed to rolling back Sandinista reforms, Chamorro so far has not presided over human rights abuses on the order of those occurring in Guatemala and El Salvador. With the Nicaraguan army and police still largely under Sandinista control, Nicaragua is the only country in Central America where the US does not exercise major influence over the military.

Despite their defeat at the polls, the Sandinistas are still a force to be reckoned with. The FSLN remains the single largest political party in the country, boasts a nationwide network of grassroots activists, and retains its dominant position in the mass organizations of such social sectors as youth, women, and farmers and in the labor movement, as well as in the military and security forces. The Sandinistas’ continuing clout has been a major factor in keeping Chamorro and her `moderate’ advisors from implementing even more strongly anti-popular policies and pushing even harder to reverse the Revolution’s gains. Unlike the faction of UNO hardliners led by Vice-President Virgilio Godoy, National Assembly head Alfredo César, and Managua mayor Arnoldo Alemán, Chamorro and her circle shy away from taking any steps which might set off a full-scale civil war. The Bush Administration and UNO’s far right-wing are unhappy that the Sandinistas are continuing to have such a strong say, and are doing their best to discredit Chamorro and destroy the FSLN once and for all.

One positive event that has occurred since UNO’s victory has been the end of the war. This was accompanied by the end of the hated draft - probably the Sandinistas’ single most unpopular policy. However, violence continues, especially in the northern part of the country. In that region, random attacks by “Recontras” (former Contras who have once more taken up arms) are terrorizing the population to the point that they are seriously interfering with travel, work, and business. Interior Minister Carlos Hurtado estimates that there are over 2,000 Recontras operating in the country. Disgruntled and in some cases actually hungry because the president has failed to make good on her promises of money and land, they are mounting ambushes, occupying farms, and stealing vehicles and cattle. Farmers are so afraid of violence that much of this year’s coffee harvest is being sold at a loss while still on the trees. Last July, a group of Recontras attacked a hydroelectric plant in the northern city of Jinotepa which produces about 25% of Nicaragua’s power. Policemen and even a mayor have been killed in other attacks.

Several hundred members of the Sandinista army have broken away and formed armed groups of “Recompas” to counter this recontra violence, but the main body of the army has refrained from doing so, fearing that taking such a move would spark a civil war or provide the pretext for a US invasion.

The returning Contras are not the only ones vying for farmland m northern Nicaragua. Rich expatriates, who abandoned large estates for Miami at the beginning of Sandinista rule, have now returned and are demanding that “their land” be given back to them. It is questionable, though, whether they ever legally owned these disputed estates in the first place, since they had originally confiscated most of the land from small farmers or campesinos. Over 60% of Nicaragua’s campesinos lost their land to the coffee barons in the late 1800s. In 1881, 5,000 peasants who refused to hand over their land were massacred. Another round of evictions took place during the cotton boom of the 1950s, resulting in still greater concentration of land ownership. In the early 1980s, the Sandinistas gave much of the country’s farmland to cooperatives or individual peasant families, and in the years since, the new owners have been using it to produce both export crops and food for Nicaraguan tables.

The Chamorro Administration’s agricultural credit policy favors loans to large farms which grow export crops

The Sandinistas’ restoration of land to those who work it is now in jeopardy. Alfredo Cesar, the former Contra leader who is now President of the National Assembly (Nicaragua’s legislature), has been spearheading a right-wing drive to repeal the land reform laws passed under the Sandinista government. If these efforts are successful (so far they have been voted down by the Assembly or vetoed by Chamorro), 20,000 families will lose their homes, 9,000 rural land titles will be annulled, and 3,400 agricultural cooperatives will be disbanded. Even if the laws are not overturned, many small farmers may lose their land by default. The Chamorro Administration’s agricultural credit policy favors loans to large farms which grow export crops. Small farmers, who need loans to buy seed, are often afraid even to apply for them because they have only their farms to use as collateral. If crops fail, as often happens due to drought or violence, they stand to lose everything they own.

When the expatriates get tired of waiting for the government to return “their” land, some hire Recontras to do so by force. Others cruise the now congested streets of Managua in their luxurious new cars, waiting.

Half of the funding sent by President Bush to the Chamorro Administration has gone for payments on Nicaragua’s $11 billion foreign debt (over $1.5 billion of it incurred by the Somoza dictatorship). Most of the rest went to former Contras. And even aid earmarked for projects that at first glance appear worthwhile often produce results of questionable value. For instance, a state-of-the-art rehabilitation center funded by USAID has left disabled Nicaraguans dependent on expensive, foreign-made equipment which could not be maintained after US technicians left.

By imposing conditions on aid and loans to Nicaragua, the US government and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) hope to pressure it into instituting a political climate which will be more favorable to private enterprise and foreign investment and which will continue the flow of resources to the US. The structural adjustment plan that the Bush Administration and the IMF have already forced the Chamorro Administration to accept has caused a drop in the inflation rate, but at a high social cost. Wages have decreased, state businesses have closed (which results in more unemployment), and government subsidies to social programs have been slashed or discontinued.

Under the terms of its free trade agreement with the US, Nicaragua has had to drastically cut import tariffs. This has led to an influx of imported goods which are much cheaper than those made in Nicaragua. Vegetables and grains are now being imported from Costa Rica while Nicaraguan farmers dump their produce in the fields because they can’t offer competitive prices.

Desperate for hard currency from any source, the Chamorro Administration is opening up Nicaragua to foreign corporations. For instance, some US companies are negotiating to dump toxic and radioactive waste off the Atlantic coast. A Taiwanese company has won a huge lumber concession under which it will clear cut most of the remaining pine forests in the North Atlantic region, and other foreign corporations are competing for the right to exploit the rich fish harvest of the Atlantic waters. The government is also moving to emphasize cultivation of export crops over that of beans, rice, and other staples for domestic consumption, a step that will lead to greater dependency on imported food and to worsening nutrition for poor families.

Despite harsh conditions that make it a challenge merely to survive from one day to the next and the formidable forces arrayed against them, many Nicaraguans continue to hope for a brighter future. Once a people has opted for revolution, successfully deposed a dictator, and briefly experienced self-determination, it is hard to beat them back into passivity. While the Nicaraguan Revolution is experiencing some serious setbacks, the days of the Somoza dynasty are gone forever, much as the Bush Administration, UNO, and some returning expatriates might wish otherwise.

Many Nicaraguans I have met are determined to hold the line against further attempts to roll back the social institutions and policies established by the Sandinistas. They feel that these were part of an effort, however imperfect, to achieve a more equitable and just society, to guarantee citizens’ human rights, and to meet the basic needs of all Nicaraguans. The Sandinista unions are pressing UNO to take emergency measures to cushion the hardest hit sectors of society, halt the decline in the purchasing power of wages, and create new sources of employment. Unions and other groups are also building coalitions to tackle common problems themselves. Many non-governmental organizations have been formed to conduct necessary studies and to provide a variety of services. Tremendous energy has gone into the formation of neighborhood groups, now organized nationally under the umbrella of El Movimiento Comunal (`the Communal Movement’). These committees of the poor have taken their survival into their own hands and -through furnishing volunteers, staffing CDIs and setting up health clinics and housing cooperatives - have provided some squatter communities with services such as water, latrines, and electricity. All of these groups operate on a shoestring, relying on innovative methods of income generation and whatever funding they can manage to attract from foreign governments and international solidarity groups. Working under exceedingly difficult conditions, they are keeping the spirit of the Revolution alive.

Letters to the Editor: Response to Newsletter #25

I was entirely disgusted by “Juan Pérez” being used to highlight the “accomplishments” of Project PROJIMO. I’m eager to support your efforts to expand health care, especially in underserved regions. That does not mean providing a haven to torturers and murderers. If I want to support people who “feel at peace” after they “kill their enemies bit by bit,” I’ll send donations to the US government and its pals.

Anonymous

I would like to commend Hesperian’s courage in printing Newsletter from the Sierra Madre #25. So many international agencies portray their beneficiaries simply as helpless victims dependent on First World donors for succor, giving the impression that all their problems will be solved by a vaccination, a water well, or a new school. In contrast, Hesperian has once again pulled aside the veil to expose the human results of systemic poverty and oppression. Hesperian shows us people who are not saints, or innocent victims, but real human beings who are struggling against greater odds than most of us have ever known, to have the things that most of us take for granted. Hesperian has placed the hard choices that some Mexicans face into a context that helps us understand the true complexity of their lives and decisions.

Beyond this, I commend Hesperian’s commitment to the PROJIMO participants as they struggle to find ways to make their project work. As the agency responsible for soliciting at least some of the funds that support PROJIMO, it must be upsetting to see that community m such turmoil, especially if that turmoil leads to actions that are difficult for American donors to understand or accept. Some donors may be concerned that their dollars are somehow supporting drug and alcohol abuse or providing a haven for violence. However, we should remember that the work at Projects Piaxtla and PROJIMO has never followed a standard approach. When David Werner first began collaborating with the people of Ajoya, the health care industry scoffed at the idea that rural farmers could learn to address the majority of their own health care needs without a physician’s help; indeed, the approach was considered dangerous. In the intervening years, the books developed by these same rural farmers, Where There Is No Doctor and Helping Health Workers Learn, have come to be considered seminal texts in health development. As PROJIMO struggles to find a balance between equality and effective administration, between compassion and justice, between personal freedom and group responsibility, who can say what insights and pioneering new approaches may emerge?

I will not say that the picture painted in the newsletter did not concern me. I wonder how many disabled children have gone without treatment because their parents were afraid to take them to PROJIMO; I find worrisome the idea that people trustingly seeking help at the project have been subjected to physical assault. I don’t know the answer or the best way to address these difficulties. But I do know that the foundation of Hesperian’s approach to development has always been faith in the ability of local people to command their own destiny, to solve their own problems. Are we willing to support them all the way? Or will we turn our backs when it gets ugly? I, for one, am grateful that at least one organization is willing to honor its commitment to the end - and to share the story with us.

Cindy Roat, Seattle, Washington

It is indeed ironic that we both find ourselves moving into the area of substance abuse after working so long in the disability field. It is becoming increasingly clear to me how much disability is caused by tobacco, alcohol, and . . . illegal drugs. In most US states the majority of serious traffic accidents involve intoxifications, so many of those with spinal cord and head injuries have a history of substance abuse. As the reality of their new disability sets in, it is not surprising that many continue to use their original intoxicant and add whatever pain killers their physicians prescribe . . . Oddly, it seems that many rehabilitation hospitals pay little attention to these phenomena.

Greg Dixon, Deputy Director, FIGHTING BACK: Community Initiatives to Reduce Demand for Drugs & Alcohol, Nashville, Tennessee

Editor’s note: We understand that many readers may have found “My Side of the Story” shocking. Our intent was not to glorify or condone the subculture of drugs and violence that is on the rise in México, but to give our readers some sense of the psycho-social disabilities it causes and the complex challenges they pose for Project PROJIMO.

PROJIMO’s philosophy has always been to avoid prejudging people, to see their untapped potential, to try to bring out the best in them. One of PROJIMO’s mottos is “Look at our strengths, not our weaknesses.” Project PROJIMO is discovering that this saying is not only applicable to people with physical disabilities, but to those with social disabilities as well.

We are happy to report that the situation at Project PROJIMO has improved since the events described in our last newsletter. After Manuel had spent four months at the Albergue de los Reyes Anti-Alcoholism Center, a group of other disabled PROMO members with substance muse problems went to visit him there and brought him back. This group was deeply impressed by the ability and commitment of the recovering alcoholics who run the Albergue. Since their return, these young people have made a sincere and mostly successful effort not to drink, and have even begun to counsel some of their peers. Also, four of the young men with spinal cord injuries who have had the greatest difficulties have become increasingly active in the wheelchair and carpentry shops. Two of them, including Juan Pérez, have become outstanding builders of rehabilitation aids, and take great pride in their work. These same individuals are also taking the lead in PROJIMO’s volunteer coordinating group.

End Matter

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |