Capitalization issues, and structure of first section.

Bad Air, Weak Blood, and Domination: African Women Confront Their Biggest Threats to Health

This Newsletter takes us to Africa (Sierra Leone and Kenya) where David Werner has recently been consulting with the World Health Organization (WHO) in an initiative to help rural women identify and seek solutions to their biggest health-related problems. The project is unusual in that its facilitators start from the villagers’ perceptions of illness and health. They look for examples of local successes in coping, rather than arriving with pre-conceived answers and instructions. Working together with village women, the researchers try to build on their traditional knowledge and survival skills. The goal is to help disadvantaged women gain more control over their health and their lives.

Bad Air

In September, 1994, in a village about 30 miles from Freetown, Sierra Leone, a research team made up mainly of African ladies met with a dozen or so poor local women. This was part of an ongoing participatory research project sponsored by WHO’s Division of Tropical Disease Research (TDR). The goal is to develop a “Healthy Women’s Counseling Guide” to help rural women better cope with their gender-related health needs, and to encourage health workers to become more understanding and responsive to women’s concerns. When this visit took place, extensive interviews had already been conducted with community leaders, health workers, traditional healers, men, and especially with village women.

Malaria was perceived as a crucial health problem that is particularly debilitating for women. In the local language malaria is called yellow fever (not to be confused with what doctors call Yellow Fever) because it causes yellowing of the eyes and skin, and dark yellow urine (due to destruction of red blood cells).

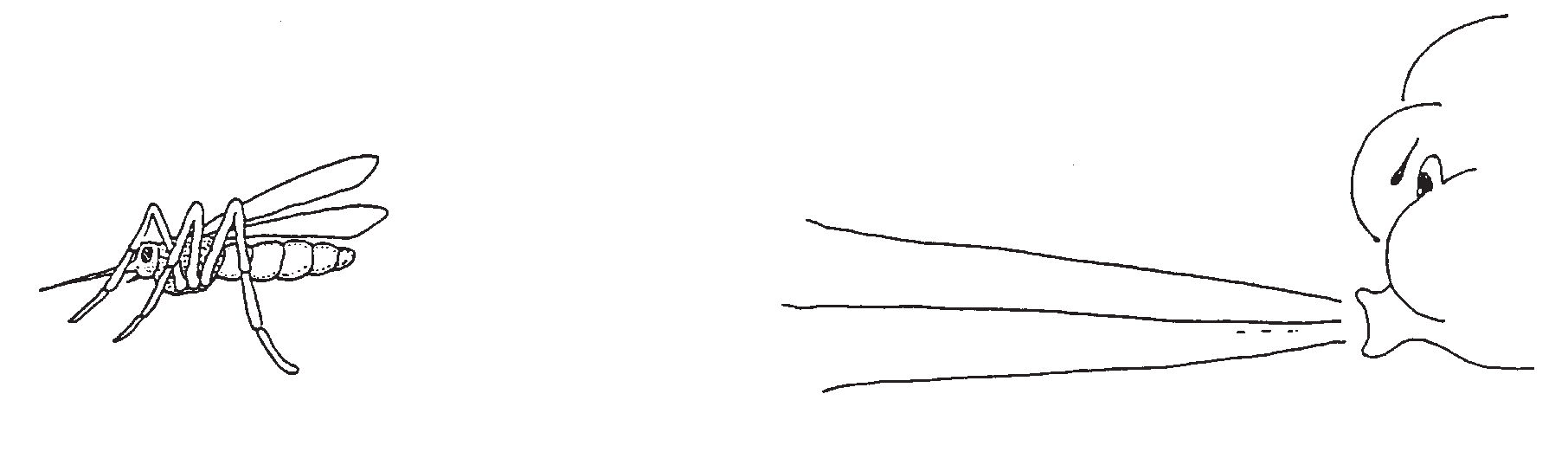

There are many local beliefs about what causes malaria. One elderly herbal healer told us it comes from “bad wind.” (Interestingly, the term malaria literally means “bad air.”) The group then conducted a demonstration showing how a mosquito spreads malaria by biting an infected person and then biting someone else . After partaking in the demonstration the old healer, undaunted, integrated her new understanding into her traditional perception. “You see, I was right that yellow fever is caused by bad wind !” she insisted “It takes the wind to carry the mosquito from one person to another.”

The old woman’s explanation may be valid. Every year in Paris, for example, several cases of malaria are recorded down-wind from the Charles de Gaul Airport. Airplanes arriving from tropical lands apparently carry stowaway mosquitos. On landing, the wind carries these mosquitos into nearby leeward communities. The epidemiology of these sporadic malaria cases is clearly wind related.

Weak Blood

In the Sierra Leone village interviews, men defined a “healthy woman” as one with a reddish complexion who had a lot of energy and could work hard. One youth, speaking of his girl-friend, said, “When I play with her hands I notice how pink and full of life they are. That is the mark of a healthy woman!” An “unhealthy woman” was seen as one who was pale: her dark skin lacked its usual reddish tone, and her palms, finger nails, gums, and inner eyelids were whitish or light yellowish. Such an “unhealthy woman” was said to be always tired and unable to do hard work. Some people said these characteristics were due to the “lack of blood” or “weak blood.”

Also the village women, speaking of their health problems, made frequent mention of tiredness, fatigue, and loss of energy. They often related ill health to problems with blood. Their most mentioned ailments had to do with “seeing the moon” (menstrual bleeding), complications in pregnancy, and child birth.

Although the fever that begins with trembling and dark urine (malaria), was viewed by all, including health workers, as one of the most important and devastating health problems, the link between malaria and anemia often was not clearly recognized. Nevertheless, in evaluating local perceptions of health and illness it was evident that paleness or weak blood (i.e. anemia) is an overriding chronic condition that debilitates most women and makes them more vulnerable to other afflictions. This also proved true in Kenya, where a rural “doctor” told us that “Here the biggest cause of death in women is anemia.”

A number of factors—biological, environmental, economic, and cultural—contribute to making anemia so severe and debilitating for rural African women. These include:

-

Menstruation. A woman’s monthly period causes regular blood loss, requiring adequate dietary replacement (iron containing foods) to prevent the development of anemia. In many Third World countries, up to 70% of women are chronically anemic.

-

Frequent pregnancy and child birth. Both pregnancy (through increased demand to build new blood for the baby and placenta) and childbirth (through blood loss during and after delivery) tend to weaken the blood. Especially in women whose nutrition is poor and pregnancies are frequent, their blood does not have time to regain its strength, so the anemia becomes more severe with each pregnancy and birth. In addition, weak blood leads to poor clotting and greater blood loss during childbirth.

-

Poor diet. The diet of poor rural women typically is high in starch and contains very little iron needed to build new blood. This leads to progressive anemia.

-

Malaria. The malaria parasite destroys red blood cells, thus causing anemia. In many parts of Africa most people have malaria, at least periodically. Malaria is especially debilitating for women because it makes their pre-existing anemia more severe.

-

Other blood-depleting diseases. Many tropical diseases (or, more correctly, diseases of poverty) cause blood loss or destruction. Among others, these include: dysentery, hookworm, leishmaniasis, and tuberculosis.

-

Male domination and women’s low social status. Many of the above factors contributing to anemia are made worse by women’s low social status and required subservience to men. Women are expected to give the best foods first to the men, then to the children, and only then to eat what is left over, if anything. Most women have little control over the choice or frequency of their pregnancies; the man does as he chooses. While women do most of the work, men control the money, often spending on alcohol what is needed for food and health care. When men have malaria, usually they buy modern medicines to treat it; but women, who often have no money, typically treat malaria with herbal remedies, which are sometimes less effective.

-

Neo-colonial domination. Structural adjustment policies imposed on poor countries by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund—which include lower wages, food production for export rather than local consumption, and cutbacks in health budgets—have led to food shortages and deepening poverty. (See pg 17.) Consequent “user financing” and “cost sharing” schemes, which require poor people to pay for medicines that were formerly free, deprive many destitute basic package of health messages. women from antimalarials, and Unfortunately, their messages are iron pills during pregnancy.

All of these factors—and many more—contribute to the aggregate worsening of anemia in women. One can not understand or hope to deal with the impact of malaria on African women without looking at the complexity of interacting factors contributing to severe anemia.

In sum, from the rural women’s perspective, weak blood or anemia emerges as the common thread which ties together many afflictions of disease and oppression and makes them clearly gender-related concerns.

Health education as an obstacle to health

On our visits to villages in Sierra Leone and Kenya, it became evident that a growing obstacle to health has been health education. In villages we visited, I was astounded that even elderly non-literate women had a vast repertoire of modern health knowledge. But they tend to be taught by rote rather than through a rational, problem-solving process. Rural areas of Africa (at least those we visited) are teaming with a spectrum of government, non-government, and religious groups dedicated to developing and indoctrinating the ’natives.’ Their interventions range from water systems, agriculture and appropriate technology to evangelism, family planning and alternative healing. But nearly all deliver a basic package of health messages. Unfortunately, their messages are often conflicting (e.g. different doses for anti-malarials taught by different groups), outdated (sugarbased oral rehydration rather than cereal-based), inappropriate (still teaching the “3 Food Groups”), impractical (“Boil all drinking water”), dependency creating (“Go to the doctor” for common ailments), or disempowering (pointing out harmful rather than helpful traditional customs and beliefs). People had been bombarded with ‘health education’ in the form of disconnected information bites unrelated to one another and to people’s real lives. As a result, every woman could parrot back a wealth of pat health messages on demand, as if that were their primary purpose. In short, health education resembled coventional schooling—a tool of cultural domination.

Mystification of Western medicine has also led to difficulties, some-times deadly. Injections of modern pharmaceuticals are believed to have more healing power than pills. So, in many parts of Africa, for malaria people insist on injectable chloroquine rather than tablets. However, an ampule has only 200 mg. Of Chloroquine, whereas a loading dose of 600 mg. (or 4 tablets of 150 mg.) is required. Thus the common use of injections leads to inadequate treatment. This not only contributes to the spread of malaria but to the development of drug-resistant strains.

Far more dangerous, for home treatment of malaria in some African countries, each family has their own syringe with which they inject any family member who has a fever. This means that if one family member has HIV, it can spread to all members. This partly explains the growing incidence of HIV in children from 5 to 10 years old. Hence, faulty information about ‘modern’ treatment of malaria is contributing to the pandemic spread of AIDS in Africa.

Inadequate health education has also contributed to people’s lack of awareness that early, adequate treatment of malaria is an important means of prevention. A standard health message is that “malaria is spread by mosquitos.” But no further explanation is given. So when we asked a group of women how mosquitos spread malaria, we were told that they picked up malaria ‘germs’ from garbage, human waste, and even from ‘dead snakes.’ Obviously people had mixed up the messages about mosquitos with messages about flies.

Teaching Tools for Thinking and Linking — About Causes, Prevention, and Treatment of Anemia and Malaria

On observing the village women’s perception of illness and health, it was evident they had a lot of health-protecting traditional practices and knowledge. However, their traditional know-how was being supplemented and eroded by modern information and beliefs (both beneficial and harmful, and often incomplete or confusing). What people lackedwas an over-arching conceptual framework into which they could fit and test the appropriateness of bits and pieces of information and knowledge, both new and old. Since paleness or weak blood (anemia) appeared to be not only a perceived indicator of poor health, but also a common thread that makes many common health problems more debilitating for women, it could become a unifying motif for health education. The research teams together with village women set about developing and testing teaching tools to help women become more aware of the interconnectedness of their different health-related problems and how they cumulatively contribute to anemia and fatigue. They considered practical measures women can take, individually and collectively, to overcome these problems.

Below we describe some of the innovations which were developed, tested, and modified with input from the village women. They have been designed to help women learn by making their own observations and drawing their own conclusions. By thinking about cause and effect, and by linking different problems and events together, perhaps they can more fully picture their situation and take action to change it.

NOTE: The activities on the following pages are experimental and have not been approved or advocated by the World Health Organization. Some health experts feel these methods and messages may be too complex or confusing for villagers and health workers. Although in Africa people are taught that mosquitos cause malaria, in some countries villagers are not taught how mosquitos spread the disease (by biting an infected person and then biting another person). It is argued that such “non-essential” information is conceptually too sophisticated, that it conflicts with the approved messages, or that it furthers the myth that mosquitos transmit AIDS. However, many of us educators feel that the best way to promote health is to provide fuller information (clearly and graphically presented) rather than withhold it. Logically, knowledge about how malaria spreads may help people grasp the importance of early treatment.

FEEDBACK WELCOMED. The village women with whom these participatory methods were developed and tested were enthusiastic and felt they learned a lot from them. But more testing is needed to find out how effectively they can be used by health workers or facilitators with limited training. We would appreciate any suggestions for improvements or feedback on trials.

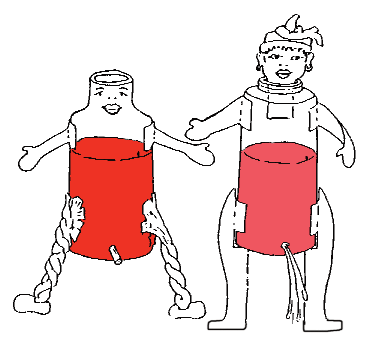

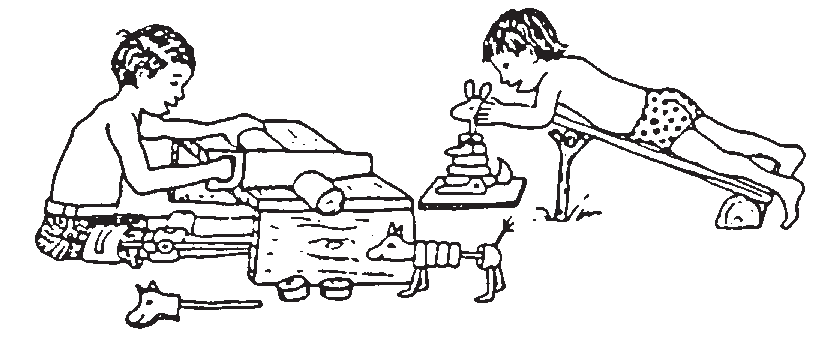

1. See-the-moon dolls for teaching about different causes of weak blood

Purpose: To help women observe how certain body functions, iron-poor diet, and illnesses contribute to increasingly severe anemia, and how eating iron-rich foods (and/or pills) helps to combat anemia.

Materials:

-

Two plastic bottles (such as baby bottles) with cardboard or

cloth heads, arms and legs, made to look like women. A hole

with a plug forms the vaginal opening. (To make the hole, push

a red-hot nail through the plastic.)

-

A liter of pretend blood made from red KoolAid or food

coloring.

Method: Have the participants demonstrate the following:

-

Menstrual bleeding. Show how the doll-women lose blood with each monthly period. Pull the plug briefly so that some ‘blood’ runs out. Replace the lost blood of one doll (we can call her Fifi) by adding plain water. (Explain that the water represents foods with little or no iron). To the other doll (we can call her Isatu), add more of the red liquid (which represents iron-rich food). After several such periods, the group notices that Fifi’s blood is getting paler, while Isatu’s blood remains rich and red. Ask the group why. (Isatu eats foods with iron; Fifi does not.) Lead a discussion about which local foods are relatively high and low in iron, and their relative prices. Why does the group think Isatu eats iron-rich foods and Fifi does not?

-

Pregnancy. Now the group pretends that both dolls become pregnant. Pregnancy can weaken the blood. (Ask how.) Isatu takes iron pills to strengthen her blood. (You might drop into her some round bits of felt soaked in concentrated red food coloring.) But Fifi can not afford iron pills. (Why not?) So her blood gets thinner still (add some water).

-

Childbirth and postpartum bleeding. Now imagine that both dolls have given birth. Each has severe bleeding after birth; (to show this, drain half their blood, then refill with water.) Ask the group how the blood of the two dolls differs. If they were real women, what would they look like? Feel like? Act like? What might be their fate? What will each need to do to get her blood strong again? How long might this take? What might happen if Fifi gets pregnant again before her blood gets stronger? How much choice does Fifi have about when she gets pregnant again? (Encourage the group to speak from their experience.)

-

Other causes of blood loss or destruction. (malaria, dysentery, tuberculosis, ulcers, etc.) Invent demonstrations to show how other important local diseases can also add to anemia.

2. Toy mosquitos that suck blood—to teach how malaria spreads, and how early treatment prevents it

Materials:

-

One or more cardboard (or tin) mosquitos made with a hypodermic syringe. Warning: Although the mosquito looks more real with a needle as its ‘beak,’ in areas where AIDS is common it may be wise to use the syringe without a needle.

-

The 2 see-the-moon dolls described above, complete with ‘blood.’ (Make a hole with a hot needle high on the plastic doll. Or if the needle will not be used as the mosquito’s beak, make a hole which the front of the syringe can just fit into. The hole should be just above the blood level in the doll, so that the doll can be tilted for the mosquito to suck blood.)

-

At least 14 ‘chloroquine pills’ made by cutting small

circular bits of white paper.

Method: Have participants demonstrate the following:

-

How malaria spreads. As a sort of role play, have the mosquito bite and suck blood from one doll, then fly to and bite the other doll, thus transmitting malaria. (Explain that malaria is caused by tiny animals or parasites that destroy part of the blood; mosquitos carry these parasites from an infected person to a healthy person.)

-

How to prevent malaria by early, full treatment. In a role play with the dolls, have the mosquito give malaria to one doll. Then at once give the doll treatment for malaria: first drop 4 paper ‘chloroquine’ pills into the doll. Then drop 2 more for each of the next 3 days (a total of 10 pills). Now have a ‘clean’ mosquito bite the doll and then bite her daughter (another doll). Ask: “Will the daughter get malaria?” Why not?

-

Dangers of incomplete treatment. Show what happens when the doll with malaria takes chloroquine pills only the first day, but because she feels better does not complete the full course of treatment. Have the mosquito bite her and then her daughter. Ask questions to help the group realize how incomplete treatment can spread malaria, whereas early complete treatment prevents transmission. Also discuss how incomplete treatment, by allowing the strongest parasites to survive, helps malaria become resistant to the medicine.

-

Malaria as an additional cause of anemia. The malaria-spreading toy mosquito can also be used together with Activity 1 (above) to show how malaria contributes, together with other causes, to dangerous or lifethreatening anemia in women. To help the group understand that blood is destroyed during a malaria attack, build on their observation that the urine becomes dark yellow. Explain that the body gets rid of the ‘dead blood’ (which turns yellow) through the urine. Then to show how malaria weakens the blood, drain off some of the blood by pulling the plug, pretending that what is now coming out is urine containing dead-blood.

3. Story telling—together with a ‘But why?’ game, and chain of causes

In the pilot projects in Sierra Leone and Kenya, the research teams designed realistic stories portraying local situations with series of interrelating events—biological, economic, cultural and political—leading to life threatening anemia. They were tested with groups of village women. After the story, the group played a “But why?” game, building a “chain of causes” with cardboard links. Some stories had 20 or more causal links. (For the basic methods see Helping Health Workers Learn, pp. 26-2 to 26-9.) Below is an example of an early, experimental story called “White Death” written in Sierra Leone.

Story of White Death

Fatu lived in a small village 70 miles from Freetown. She worked hard growing what food she could on a small plot with poor soil. Often there was not enough to eat, especially in the rainy season, and she always gave the best to her husband and her children. For over a year her health had been poor and she always felt tired. Her palms, gums, and tongue were pale and yellowish. The village nurse said Fatu was anemic—that her blood was weak because her food lacked iron to replace the blood she lost each month when she saw the moon. The nurse told her to eat lots of red meat, liver, and the like. But that made no sense. With what was she to buy such costly foods?

During her initiation years ago, I had taught Fatu that potato leaves help strengthen the blood. So she began to eat more of them. But she cooked them a long time in a lot of water and threw out the left-over water (with most of the vitamins and iron). Such was the custom. Her hands and gums kept getting more pale.

Fatu raised a few chickens but never ate them because she needed the eggs. She sold the eggs to buy modern medicine when her children had diarrhea, coughs, and colds. In the past she had given them rice gruel for their diarrhea and herbal teas for their colds. These had seemed to work well. But one day a traveling drug salesman called “Doctor” told Fatu she was irresponsible. He said, “If you want to keep your children alive and healthy, you must treat their ailments with real medicines, like these.” So Fatu sold eggs to buy cough syrups and packets of Oral Rehydration Salts. But her children grew thinner and got sick more often. There were not enough eggs to pay for all the medicines. So she began selling the beans. Now she and the children ate only rice with overcooked greens.

Another reason Fatu’s blood was so weak was malaria. She had suffered bouts of malaria since childhood. But now the fevers were worse and lasted longer. In the past she had treated her malaria with a special herb that grew only in a beautiful forest near the river. But two years ago, a rich man from Freetown arrived with a permit to cut down the forest and plant cocoa trees. (This was part of the new “production for export” policy imposed by the World Bank to make sure Sierra Leone kept up payments on its big foreign debt.) The special herb for malaria disappeared with the forest. Fatu now used another herb, but it didn’t help much. And she didn’t have money to buy Chloroquine.

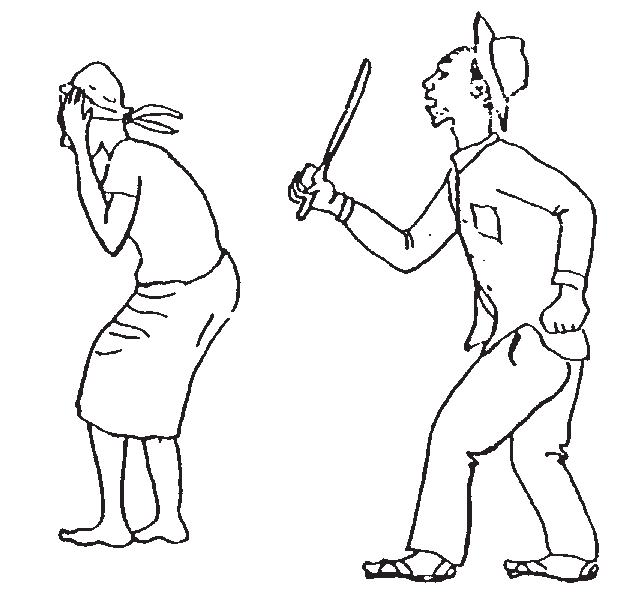

A digba is a ‘wise woman’ who performs female circumcision on pubescent girls and presides over their initiation into the Bondo Society, a Moslem order of women to which nearly all Sierra Leone women belong. The ceremony, in which girls are secluded together for weeks, includes training in womanhood, health care, and skills for survival in male-dominated society. Even many highly educated women feel this initiation into womanhood and female solidarity is so important that they insist their daughters be circumcised. Some members of the research team in Sierra Leone think that involving digbas and the Bondo Society in facilitating the WHO “Healthy Women Counselling Guide” project will be essential to its success—and that little by little, circumcision can be reduced to a minor, largely symbolic procedure, similar to male circumcision in the West. This less harmful alternative, known as “European circumcision,” is already becoming more popular in many parts of Africa.

When Fatu got pregnant she went to get iron pills, as she had done with earlier pregnancies. For pregnant women iron pills used to be free. But now, at the Bamako pharmacy she was told she had to pay for them. (This is part of UNICEF and the World Bank’s new cost-recovery scheme). Fatu explained she had no money. But the dispenser told her she wasn’t indigent" enough (whatever that meant) to qualify for free iron pills, since her husband had a job.

This was true, although her husband gave her no money. Most of what he earned he spent on drink. And when he was drunk, he beat her.

However Fatu’s husband liked to hunt. Sometimes he brought home small game. But with so many hungry mouths, the meat never went far. The digba had told Fatu that the vital organs of animals and birds were extra good for strengthening the blood. Fatu thought of asking her husband to give them to her. But according to custom the man had a right to these delicacies, and she was afraid to ask him.

When Fatu became pregnant again, her youngest child was only eight months old. She had wanted to wait longer, but had little choice. With the last birth she had lost more blood than usual, and was still pale and weak. With the frequent bouts of malaria, it had taken longer to get back her color and strength. She had heard talk of a medicine to prevent pregnancy, but at the Mosque they said it was work of the Devil. So against her better judgement, Fatu was pregnant again, and gradually became weaker and more pale. By the ninth month her palms were sickly white and her feet more swollen than usual. As her time to deliver grew near, she felt increasingly exhausted.

When her time finally came, Fatu went to the trained birth attendant. The TBR at once saw that she was dangerously anemic and said she should go to the hospital. But the hospital was a long way away, Fatu’s pains were already frequent, and there was no ambulance or public transport. To pay a driver was out of the question. So the midwife attended the birth. It took longer than usual since Fatu lacked the strength to push hard. At last the baby came out, small and thin.

After the delivery Fatu bled and bled. The blood was so thin you could see through it. The midwife gave the woman medicines and herbs to control the bleeding. After a long time the bleeding stopped, but Fatu was haggard and drained. She was too weak to walk home and had to be carried. A kindly neighbor woman helped take care of her. And so did her husband, who for the first time seemed genuinely concerned. He even bought her iron pills. But as the days went by, her strength was very slow in returning. The dispenser said the iron pills would take months to strengthen her blood.

Then, a month after Fatu had given birth, the chills and fever of malaria struck again, worse than ever. Her husband bought Chloroquine tablets. He asked the dispenser if the rumor was true that Chloroquine no longer worked and a new medicine was needed. But the dispenser said, whether it worked or not, Chloroquine was still the only anti-malarial medicine on the Bamako Essential Drug List.

After the malaria attack Fatu’s hands and tongue looked whiter and yellower than ever. Lying in bed, she breathed as hard as when she used to climb a hill with a load of firewood.

One night when her husband and children were sleeping Fatu quietly died. Some people said she had been hexed. But the digba called it the White Death and said that for women it was normal.

Note: The above story, “White Death,” was eventually replaced by a story in which the main character nearly dies, then recovers and helps other women to avoid or find a way through similar difficulties. (Village women said they didn’t want the main character to die.) The advantage of the later story is that it presents solutions as well as problems. However, there is probably a place for both types of stories.

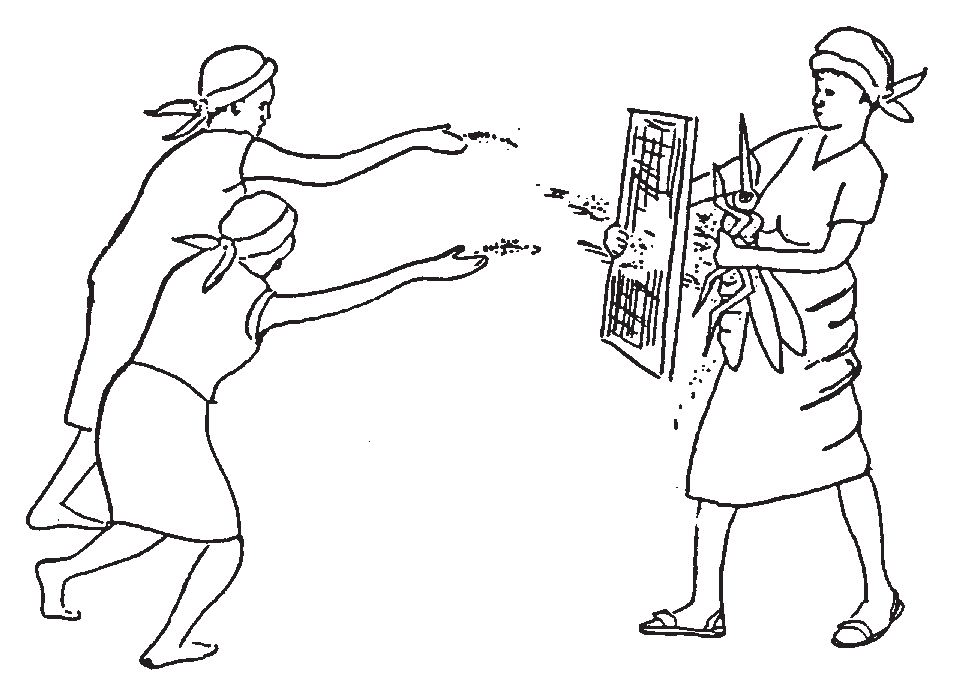

In experimenting with this methodology, the researchers in Kenya found that placing line drawings of each cause next to every chain link made the sequence clearer. The pictures serve as reminders for facilitating follow-up discussion (when the group considers which links can be broken through individual and through collective action.) On the next page is a series of drawings that accompany a chain of causes for a story in Sierra Leone. The pictures were tested with groups of the village women. Most of the drawings, done by a local artist, were well understood even by non-literate women. A few still need changes.

4. IDEAS FOR TEACHING ABOUT RESISTANT STRAINS OF MOSQUITOS, PARASITES, AND PEOPLE

Introductory Thoughts

An ancient Greek philosopher said: “You cannot step in the same river twice.” This observation is not just philosophical. It is both practical and important.

Too often health messages, as they are taught, appear to be carved in stone. This is the result of topdown, authoritarian teaching. The instructor knows it all, and the heads of the students are like empty pots to be filled. In such an approach to learning, science becomes absolute and unchanging, like the word of God (according to the priests).

But reality has a different—and more interesting—story. Science, like all human knowledge, is constantly changing and evolving. So are the creatures it studies. Therefore, if health education is to prepare people for the changing reality within which they live, it must reveal its own limitations. Participants need to realize that many of the health messages we learn today may need to be modified tomorrow. This is not a weakness of scientific knowledge, but its most crucial strength. If improvements in health are to be sustainable, health education (for both villagers and doctors) must prepare learners always to compare what they have been taught with the reality in which they live. We need to keep our eyes open and minds flexible. Teachers and students alike, we must always be looking for new information, more appropriate ways of doing things, better ways to adapt to our changing environment . . . and to the changes within ourselves.

One way to help get across the idea of change—in science and in living things—is to look at patterns of resistance: the way different creatures develop a defence against those things that try to destroy them.

When looking at the management of malaria, we see that development of resistance—by mosquitos, by the malaria parasite, and by people—to their respective enemies plays an important role in the changing management of this still uncontrollable disease. We see that:

-

MOSQUITOS have become resistant to pesticides. This means that new pesticides must be developed to kill mosquitos. Or other, more suitable forms of control must be used. Today some pesticides kill the mosquito’s natural enemies, like house spiders, but not the mosquitos. So continued spraying has often led to more mosquitos and more malaria.

-

THE PARASITE that causes malaria (Plasmodium), which is carried by mosquitos from person to person, in many areas has become resistant to the most used anti-malaria drug, Chloroquine. New drugs are being developed and introduced. But in some areas, malaria has become resistant even to the newest drugs. In such places, quinine and other ancient herbal treatments may work better than any ‘modern’ medicine. People who get malaria need to be kept up to date on these changing patterns, and adapt accordingly. So do health workers.

-

PEOPLE also can become partially resistant to the malaria parasite. If a person from Europe goes into an African village without taking preventive medication, he will get malaria far more severely than most of the local people. From repeated infections with malaria since childhood, local people’s bodies have developed some resistance. The outsider has not.

Helping People Understand How Mosquitos Develop Resistance to Insecticides

Objectives: Help people understand that:

-

Mosquitos spread malaria by biting a person with malaria and then biting another person.

-

Mosquitos gradually become resistant to specific insecticides, so new measures are needed.

-

Mosquitos develop resistance faster when control measures are incomplete, allowing the toughest mosquitos to survive and multiply. They breed a new, more resistant race of mosquitos.

-

In a similar way, malaria becomes resistant to antimalaria drugs. So new drugs are needed.

-

Malaria and many other diseases are becoming resistant to drugs that used to cure them, partly because people often do not take medicine correctly in the full amount.

-

Taking medicine correctly—as much and as long as recommended—helps prevent resistant forms of disease from developing. This is important because some forms of malaria and other diseases are becoming so resistant that no drugs can stop them, so they kill more people.

Method: A role play (or village theater presentation).

Materials needed:

-

A giant cardboard mosquito (Participants can make it.)

-

A big wire mesh for sifting gravel.

-

Small rocks (a little bigger than the holes in the sieve)

-

Sand

In this role play, one person plays the mosquito, holding the giant cardboard insect. The mosquito flies around, buzzing and biting people. It carries malaria from persons with malaria to others.

The people decide to kill the mosquito, so they buy an insecticide (a batch of small rocks). From a distance, they throw the rocks at the mosquito, which tries to dodge them. When the mosquito is hit by 10 rocks, it dies. [The 10 rocks may call to mind the 10 chloroquine pills needed to cure malaria.]

Then another mosquito comes. The people again throw rocks at it, and when the mosquito is hit by 4 rocks it falls to the ground. Thinking the mosquito is dead, the people stop throwing rocks. But the mosquito recovers and flies away.

Hiding in a corner, the mosquito says: “If I get hit by more of those deadly insecticide rocks, I’ll die. I need some kind of defence.” The mosquito (or rather the person holding the mosquito) picks up the wire mesh, saying. “This will be my shield to protect me against the insecticide rocks!”

So the mosquito flies around, shielded by the mesh. The people again throw rocks at it, but the rocks bounce off the mesh. The mosquito continues to bite people and spread malaria.

The facilitator challenges the participants: “The insecticide no longer kills the mosquito. Its defence is too strong. It has become resistant. What other forms or mosquito control could we use?”

Participants might give various suggestions: mosquito nets, coils, smoldering cow dung, stink-stink leaves, burying broken pots, etc.)

The facilitator asks, “Can you think of a new variety of insecticide that will get through the mosquito’s shield?” If necessary the facilitator gives more cues: “The insecticide is these little rocks. They can’t get past the mosquito’s defenses. But can you think of something similar that will go through the holes in the mesh.”

The learning group tries to think what this could be. “Sand!” cries someone. “It is just ground up rocks, but it will pass through the wire mesh.”

So the people throw sand at the mosquito. Its defense (the mesh) provides no protection. When the sand hits the mosquito, it dies and everyone celebrates.

Discussion and Questions:

This activity is followed by a discussion of resistance: of insects to insecticides, of malaria to anti-malaria drugs, and of people to malaria. Ask questions that reinforce the key messages developed through the activity (see list of objectives). Also ask questions that help participants to relate the new knowledge to their own reality and take health-protecting action. For example:

-

“The next time you get malaria, how will taking the full 10 tablet treatment of chloroquine make it more likely that this medicine will continue to cure your future attacks of malaria?”

-

“Have any of you found that when you last took chloroquine, it didn’t seem to help? Or that it doesn’t work as well as it used to? What could be the reason?” [Possible answers: Perhaps the illness was not malaria. Perhaps you did not take the drug correctly, or long enough. Perhaps the malaria you have is resistant to chloroquine.] “If you don’t get better with Chloroquine, why is it important to seek medical help?”

Also ask questions that help people expand their understanding of the key ideas. For example:

-

“Why is a visitor from Europe likely to be much more severely affected by malaria than you are?” [Because you have built up partial resistance to malaria, and the outsider has not.]

-

“What other diseases do you know about that hav become resistant to treatment?” [After listening and responding to answers, you can explain that certain dangerous diseases—typhoid fever, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, some forms of pneumonia, and sudden, bloody diarrhea with fever (Shigella), etc.—have in many places become resistant to different medicines and are now much harder to combat. Advise participants about the drug-resistant diseases in your area.]

Note: This Resistance Activity was tried in an area where mosquito control with insecticides have never been used. People were therefore confused. However, in other areas the activity may be useful. More trials are needed.

News from Mexico

PROJIMO, the community-based program run for and by young disabled villagers in the mountains of Western Mexico, has passed through difficult times, but now appears to be making a new start. In the last several years, fewer chilren have been brought to this remote rural center. One of the reasons is that PROJIMO has given rise to a number of other community-based programs for disabled children, located in coastal cities and more easily accessible areas.

From children to young adults. If PROJIMO has fewer children, the number of young adults has increased. Over the past few years PROJIMO has helped meet the needs of over 300 spinal cord injured youths. Most have been disabled by bullet wounds, in the growing sub-culture of violence resulting from increasing poverty and unemployment that leads to drug trafficking, drug use, and crime. The PROJIMO team has done its best to provide these youth with both physical and psycho-social rehabilitation. There have been many disappointments and much frustration. However some of these desperate young people have found new directions and became capable and caring workers. PROJIMO is virtually the only program in Mexico that tends to their needs — or rather helps them tend to one another’s needs.

Community control. In order to make its services more accessible to families of disabled children from a wider area, the PROJIMO team considered moving the center to a village nearer the main highway. But the village of Ajoya protested. The villagers said they had been involved and supportive of the program from the start and were determined to keep it in their village. So the team has decided to stay, and with a new sense of community solidarity has renovated the Playground for All Children. The new merrygo-round provides constant entertainment for both disabled and nondisabled village children.

From rehabilitation to independent living. In the last few years PROJIMO has increasingly become a sort of independent living initiative for disabled young adults. Its focus has increasingly turned toward acquiring work and organizational skills for income generation. The team has improved the quality and rate of production of low cost wheelchairs, and recently UNICEF Mexico has been buying PROJIMO wheelchairs for other disability programs in Mexico. PROJIMO is also eager to upgrade its carpentry and toy-making shops, in order to produce and find markets for attractive and useful items that can be sold.

The quest for self-sufficiency has become more urgent because since the introduction of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) many progressive European funding agencies have stopped supporting Mexican initiatives, feeling that Mexico is now under the dominion of the United States.

Intensive Spanish Language Training Program for visiting Northerners. Spanish courses were initiated several years ago as a way of providing skills training and work for disabled persons, especially those with quadriplegia and other physically very limiting disabilities. Due to lack of a qualified teacher the program was interrupted. But now a group of capable disabled persons is eager to revive the venture and make it work.

In this Newsletter you will find an insert announcing the new Intensive Spanish Language Training Program. (Editor’s note: This insert is missing.) It caters to disabled activists and rehabilitation workers, but welcomes anyone interested in learning Spanish in a unique and informal situation. We should point out that the program is mainly for persons who already know a little Spanish and wish to improve it. The team especially welcomes students who, as they learn, will help the instructors upgrade their teaching skills. If you are interested in this Spanish program or know anyone who is, let us know.

A new cycle of courses for disabled rehabilitation workers and activists. An emerging informal network of community-run disability programs in Mexico and Central America is planning a 2-year series of short courses and workshops. Courses will be held in the center most qualified in the specific field. For example, PROJIMO will lead the wheelchair-making course and a workshop on grassroots management. Other courses will cover everything from brace making and physiotherapy to disability rights and sexuality. Since funding is becoming more difficult to obtain, participating programs are asked to cover the cost of their representatives. But some funding is needed for scholarships and other costs. Is anyone able to help? Any ideas?

Save Our State from Proposition 187

Anti-immigrant sentiment has been growing steadily in California over the last few years as citizens and government officials have been struggling with economic hardship and looking for a scapegoat. In the state-wide election last month Californians approved Proposition 187 by a wide margin, a misguided effort that is undermining California’s foundation, both economically and ethically.

The so-called “Save Our State” (SOS) initiative was written to deny education and health care to illegal immigrants as a shortsighted attempt to save money. The proposed law would prohibit illegal immigrants from utilizing public education and public health services (except in cases of emergency) and require teachers and health care professionals to report illegal immigrants to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).

Although there is a good chance the measure may never be enacted (the American Civil Liberties Union and half a dozen other groups have filed lawsuits to prove it is unconstitutional), in many ways the damage is already being done as some people are afraid to use the public services they need and feel ostracized by the communities in which they live.

California, as the rest of the United States, is populated almost entirely by immigrants and their descendants and we continue to attract more everyday. Although the number of people entering California illegally is difficult to determine, the Urban Institute estimates that for most years from 1980 to 1992 between 2.5 million and 4 million people crossed the US borders illegally, and nearly half of those came to California. Contrary to popular belief, the men, women and children who come to the United States arrive from all over the globe; Mexicans make up no more than 55% of people who are in the country illegally. And while more than three million people illegally cross the USMexican border each year, more than nine out of ten return home.

Health care

This initiative would deny illegal immigrants and their children access to all but emergency health services. From a public health standpoint, it’s difficult to understand how millions of children foregoing prenatal care and vaccination can possibly save California any money in the long run. This aspect of the bill also poses a number of other questions, both humane and economic. Have the voters of California become so callous that we would tell a mother not to take her sick child to a public clinic for care until it becomes an emergency? Most ailments, when attended to early, are easier to treat, have a better chance for successful treatment, cause less suffering to the patient, and are less costly to the health care sys tem. By asking people to wait until sicknesses become emergencies, we are asking people to risk their health, to suffer more, and ultimately, to cause the already high cost of medicine to continue to skyrocket. Emergency rooms are going to be overcrowded with people who should be seeing health professionals on a non-emergency basis, but instead are at the emergency room (the most expensive of medical services) because they are not allowed to receive treatment otherwise.

Education

In 1982, in an opinion written by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., the Supreme Court ruled that undocumented immigrant children had a right to go to school. He said that education has “a fundamental role in maintaining the fabric of our society.” Proposition 187 would prevent children from attending school, thereby establishing the legally questionable and socially intolerable situation of enforced truancy. To say that preventing illegal immigrants from attending school will save California money is palpably false; California stands to lose approximately 3.4 billion dollars in federal education funding if it expels students from its schools who cannot prove they are here legally.

Loss of Federal Funding

If Proposition 187 is enacted, California could lose more than $15 billion every year in federal funding. This is because federal law mandates that school and medical records be kept confidential unless the student or patient gives permission for the release of that information. Violating these federal laws would be grounds for the federal government to withhold payment. Elizabeth G. Hill, the Legislative Analyst of the State of California, wrote (in the 1994 Ballot Pamphlet booklet that was sent to every voter in the state) that the fiscal effect of this proposition would be to save “in the range of $200 million annually.” These savings would be immediately offset because the costs of implementation are estimated to “be in the tens of millions of dollars, with first-year costs considerably higher (potentially in excess of $100 million).” Both of these figures are peanuts compared to the $15 billion in federal funding that California stands to lose if this proposition should fully be put into effect.

The proponents of Proposition 187 claim that it will “save our state” from economic disaster because illegal immigrants cost so much money. Critics of illegal immigrants often cite three reasons for wanting to prevent illegal immigrants from living within our borders: job scarcity, lack of tax revenue and overuse of public services. Each of these rea-sons are based on misconceptions that are rooted in cultural myth or, in some cases, purposeful disinformation.

Jobs

It is true that one of California’s primary attractions for immigrants is jobs. In 1986 President Reagan’s top economic advisors told Congress that “while they were not condoning illegal immigration, they could find no evidence that the employment of illegal aliens displaced nativeborn workers from jobs.” Even Governor Pete Wilson, who has been one of the most ardent supporters of Proposition 187, knows illegal immigrants are an important part of California’s economic and employment picture. In 1986 he championed a key provision that facilitated the continued supply of inexpensive farm labor. After that provision passed, Senator Wilson bragged that it “would guarantee decent housing, workmen’s compensation, and other benefits for the seasonal farm workers.”

Taxes and Public Services

The American revolution was partially instigated by the objection to taxation without representation. Ironically, this is exactly the position in which many illegal workers find themselves. They pay the same sales taxes on the items they purchase as anyone else yet are being denied some of the essential services that tax money provides. Officials in government know that illegal immigrants pay more than their fair share of income taxes. President Reagan’s council of economic advisors reported in 1986 that “Illegal aliens may find it possible to evade some taxes, but they use fewer services than do other groups.” They go on to say that “The chapter [in the report] on immigration became controversial . . . [because] the President’s economic advisers had been forced to delete comments saying that proposals to punish employers of illegal aliens would have adverse effects on the economy.” (italics added) In other words, Reagan’s economic council suppressed evidence that proved illegal immigrants have a positive effect on the economy!

Here in California, the argument becomes blatantly racist. Richard Simon of the Los Angeles Times reports that “The Orange Countybased Coalition for Immigration Reform includes the statement: ‘Facts and figures repeatedly prove that illegal aliens, first committing a criminal act by violating our borders and then bringing their values and culture into our midst, are major contributors to our mounting financial burdens and moral and social degradation.’” (italics added)

What this all means is that members of our government know that workers who are in the country illegally actually enhance the economy, but because of their own bigotry they are suppressing that information while promoting ideas to the contrary.

One of the economic arguments about illegal immigrants not paying their fair share of taxes seems at first to have merit, but upon closer scrutiny is revealed to be a problem of unfair distribution of the taxes they pay. Ken Silverstein of Scholastic Update writes “economists also note that illegal immigrants not only pay sales tax on purchases, but—because they often fake documents to obtain employment—have social security and federal income taxes withheld from their paychecks. Few dare file for a refund, so that money remains in government coffers.” But the burden of supplying public services falls primarily on the state and counties. If the federal government would give to the state the amount of profit it receives from illegal immigrants who pay into federal coffers but do not collect federal services, California would have no difficulty in paying for the necessary services to keep all of the peo-le in its territory safe, well and educated. Perhaps the reason the borders are so leaky is because it is so profitable to the federal government to spend a minimal amount on border patrol while collecting billions of dollars in taxes for services they will never render.

Enforcement

Proposition 187 requires educators, health care professionals and police to report people whom they suspect of being illegal immigrants to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. On what basis should a person be suspected? This regressive legislation paves the way for “legal discrimination” based on whether a person’s skin is dark or if they speak with an accent.

Appropriate Response

As a student in a California Community College and as an occasional patient in our health care system, I feel strongly that it would be unethical for me to participate in this racist, misguided assault on this state’s immigrants. Therefore, if Proposition 187 is enacted, I encourage all students and patients to join with me in refusing to show proof of citizenship to those who have been assigned to turn in those of us who do not have them. We must stand together in solidarity to protect one another from the ugliness and hatred of bigotry. I urge teachers and health care providers, who work hard in the service of our communities, to flood the INS with the names of everyone who attends their classes or goes to them for medical care. By flooding the INS with millions of false guesses as to who is in the country illegally perhaps we can show the fallacy of this fascist initiative and overturn it.

Conclusion

Those who fought the hardest against the fair treatment of illegal immigrants grossly misled the people of California by placing the blame for all of our problems on them. This is not the first time in history that this kind of tactic has been used. As Hitler blamed the Jews for the problems of Germany in his era, today we see the horrors of racial hatred and scapegoating in Bosnia and Rwanda.And the Jews are being blamed once again: this time in Russia by Vladimir Zhirinovsky whose party garnered 25% of the vote in the last Russian presidential election (75% of the vote of the military). I had always thought that in America we were safe from that kind of terrorism, but Proposition 187 is as dangerous a step towards fascism in this country as I have ever seen. I am appalled and sickened that more than 59% of Californians have been seduced into the temptation to blame their problems on a minority that cannot even vote to defend itself.

All people are entitled to basic human rights. We must work together to protect the health and rights of our neighbors. Proposition 187 is a macabre deception which, if implemented, will further fracture our already troubled society. If the courts don’t overturn Proposition 187, it will be up to the people affected by it: and those people include all of us.

The World Bank: Turning Health into an Investment

The World Bank

Fifty years ago in the village of Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, representatives of 44 nations convened to discuss the international monetary and financial system. What emerged from that meeting was the birth of two new global bureaucracies: the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The purpose of these new institutions was to fix international exchange rates and to provide stability and structure to the international monetary order in the hopes of avoiding a repetition of the economic chaos and disaster of the 1920s and 1930s.

The IMF was given the power to adjust exchange rates to reflect the changing value of different currencies. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the full name of the World Bank) was supposed to finance projects for reconstruction after World War II and to assist in the development of underdeveloped regions. And indeed they did, although most of what they funded were grandiose projects that put more wealth into the hands of the wealthy, while often displacing thousands of poor people from their homes.

Structural Adjustment Programs

By the early 1980s, many poor countries were seriously in debt, and were having difficulty paying even the interest on their loans. As the people at the banks in the wealthier countries realized that they were not going to be repaid on many of the irresponsible loans they had made, they began to refuse to lend additional money, causing many poor countries great economic hardship. As it became clear that some of these countries were going to default on their loans, as Mexico did in 1982, the World Bank and the IMF came to the rescue—of the banks!

The World Bank and the IMF loaned money to struggling countries with strings attached that tied them in knots. As a condition of accepting these new loans, governments had to agree to accept structural adjustment programs (SAPs) as well. The Bank claimed that the SAPs would improve the economic climate in the countries in which they were imposed by reducing the governments expenditures.

Briefly, the SAPs usually include the following components:

-

cutbacks in public spending (usually on health and education)

-

privatization of government enterprises

-

freezing of wages and freeing of prices

-

increasing taxation (of the poor and middle class)

-

increasing production for export rather than for local consumption

-

reducing tariffs and regulations and creating incentives to attract foreign

-

capital and trade (often resulting in dangerous environmental hazards)

-

reducing government deficits by charging user fees for social services,

-

including health

For a long time, the administrators at the World Bank denied that structural adjustment hurt the poor, but more recently it says that such austerity measures (starving children?) are necessary to restore economic growth. They assert that as countries get richer, eventually some benefits will trickle down to the poor. But overwhelming evidence shows that structural adjustment, linked with other conservative trends, have caused major set-backs in the health of poor families. While the Bank shows graphs that have been stripped of their fine detail in order to show that overall health statistics are better now than they were thirty years ago, upon close inspection of the data it is clear that in many countries improvements in health have slowed down or stopped since the 1980s, and even more so in the 1990s.

These structural adjustment programs were tantamount to making the poor pay for the irresponsible lending by the rich banks in Northern countries to the rich elites in the South. Not surprisingly, they have had devastating effects on the health of poor people in the countries to which they have been applied.

The widening gap between rich and poor has been exacerbated by Third World governments’ attempts to comply with the World Bank’s policies. Despite development aid from a number of Northern countries, in the 1990s more than $60 billion net flows from the poor countries to the rich each year. Meanwhile, nearly 25% of the world’s people lack adequate food (even though ample food supplies exists) and the gap between rich and poor has grown 30% in the last ten years.

Investing in Health

The World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report is entitled Investing in Health. On first reading, the Bank’s strategy for improving health status worldwide sounds comprehensive, even modestly progressive. It acknowledges the economic roots of ill health, and states that improvements in health are likely to result primarily from advances in non-health sectors. It calls for increased family income, better education (especially for girls), greater access to health care, and a focus on basic health services rather than tertiary and specialist care. It quite rightly criticizes the persistent inequity and inefficiency of current Third World health systems. Ironically, in view of its track record of slashing health budgets, it even calls for increased health spending. Furthermore, it echoes the Alma Ata call for community participation, self-reliance, and health in the people’s hands. . . So far so good.

But on reading further, we discover that under the guise of promoting an equitable, costeffec-tive, decentralized, and country-appropriate health system, the World Bank’s key recommendations spring from the same sort of structural adjustment paradigm that has worsened poverty and further jeopardized the health of the world’s neediest people.

In the report, the Bank introduces a new unit of measure called the Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY), a method for calculating which maladies governments should allocate funds for, based on a person’s ability to contribute to the country’s productivity (GNP). Here’s how it works. Each disease is given a value, an approximation of how many years of healthy productive life that a person is likely to lose if they are stricken with a particular disease at a given age. This is weighed against how much it costs to prevent or treat that disease. For example, vitamin A supplementation in areas with a high risk of blindness is cost effective because it costs less than $1 per DALY, whereas treating children with leukemia is much less cost effective at $10,000 per DALY.

Because of the way DALYs factor age, children and the elderly have lower value than young adults, and presumably disabled persons who are unable to work are awarded zero value and therefore have little or no entitlement to health services at public expense. (The very term Disability Adjusted Life Years is an affront to disabled persons.The DALY prioritization method which authoritatively deprecates disability has the stench of eugenics. Disabled activists need to join with health rights activists to protest this potentially neo-fascist policy.)

The Bank says that using the DALY “avoids assigning a dollar value to human life,” but nothing could be further from the truth. The Bank takes a dehumanizingly mechanistic marketplace view of both health and health care. When stripped of its humanitarian rhetoric, its chilling thesis is that the purpose of keeping people healthy is to promote economic growth. Were this growth to serve the well-being of all, the Bank’s intrusion into health care might be more palatable. But the “economic growth” which the Bank inflexibly promotes as the goal and measure of “development” has invariably benefitted large multinational corporations, often at great human and environmental cost.

The World Bank tries to convince us that it has turned over a new leaf: that it now recognizes that sustainable development must take direct measures to eliminate poverty. Yet the Bank has so consistently financed projects and policies which worsen the situation of disadvantaged people that we must question its ability to change its course. A growing number of critics suggest that perhaps the most effective step the World Bank could take to eliminate poverty would be to eliminate itself.

According to the Bank’s prescription, in order to save “millions of lives and billions of dollars” governments must adopt “a three pronged policy approach of health reform:

-

Foster an enabling environment for households to improve health.

-

Improve government spending in health.

-

Promote diversity and competition in the promotion of health services.”

These recommendations are said to reflect new thinking. But stripped of their Good Samaritan face lift, and reading the Report’s fine print, we can restate these three prongs more revealingly:

-

“Foster an enabling environment for households to improve health” means requiring disadvantaged families to cover the costs of their own health care . . . in other words, fee for service and cost recovery through user financing: putting the burden of health costs back on the shoulders of the poor.

-

“Improve government spending in health” means trimming government spending by reducing services from comprehensive coverage to a narrowly selective, cost-effective approach . . . in other words, a new brand of Selective Primary Health Care.

-

“Promote diversity and competition” means turning over to private, profit-making doctors and businesses most of those government services that used to provide free or subsidized care to the poor . . . in other words, privatization of most medical and health services: thus pricing many medical interventions beyond the reach of those in greatest need.

In essence, the Bank’s strategy is a market-friendly version of Selective (rather than Comprehensive) Primary Health Care, which includes privatization of medical services and user-financed cost recovery. One reviewer (David Legge) observes that the World Bank Report is “primarily oriented around the technical fix rather than any focus on structural causes of poor health; it is about healthier poverty.”

The commercial medical establishment and some large non-government organizations have celebrated the World Bank’s Investment in Health strategy as a ‘major breakthrough’ toward universal, more cost-efficient health care. But most health rights activists see the report as a master-piece of disinformation, with dangerous implications. They fear that the Bank will impose its recommendations on those poor countries that can least afford to implement them. What makes the new health strategy especially dangerous is that the Bank, with its enormous money-lending capacity, can force poor countries to accept its blueprint by tying it to loans as it has done with structural adjustment.

A Call for Organized Protest of the World Bank’s Intrusion into Health Policy Making

Despite all its rhetoric about alleviation of poverty, strengthening of households, and more equitable and efficient health care, the central function of the World Bank remains the same: to draw the rulers and governments of weaker states into a global economy dominated by large, multinational corporations. Its loan programs, development priorities, and adjustment policies have deepened inequalities and contributed to the perpetuation of poverty, ill health, and deteriorating living conditions for at least one billion human beings.

In various parts of the world, concerned groups are attempting to engender a broad-based protest of the pernicious policies of the World Bank and IMF. Health Action International has put together a packet of writings from a wide variety of sources, criticizing the 1993 World Development Report and alerting health activists to oppose it. Covering a broader critical analysis, “50 Years Is Enough” is an international coalition organized around the 50th anniversary of the World Bank and IMF. Involving scores of environment, development, religious, labor, student, and health groups, it represents an unprecedented worldwide movement to reform these International Financial Institutions. At the same time, many groups and networks around the globe are working on health and development issues from a grassroots perspective, trying to listen and respond to what people want. They are attempting to create broad public awareness of our current global crisis, and to organize a groundswell of pressure from below on the world’s policy making bodies. The Christian Medical Commission has long carried an outspoken voice of conscience in these matters. So have two grassroots coalitions based in the South: the Third World Network with its coordinating body in Malaysia, and the International People’s Health Council, based in Nicaragua.

It is urgent that all of us concerned with the health and rights of disadvantaged people become familiar with the World Bank’s Investing in Health Report. We must speak out clearly about the harm its policies are likely to do, and clarify whose interests those policies serve. Never has the need been greater for a coordinated global effort to demand that world leaders and policy makers be accountable to humanity.

To become better informed about the full range of objections to the Report and the World Bank’s controversial prescription for health, you can write to:

Health Action International— Europe

Jacob van Lennepkade 334 T

1053 NJ Amsterdam

The Netherlands

For more information on the “50 Years is Enough” campaign, the groups involved, and a calendar of events, you can contact:

The Bank Information Center

2025 I Street, NW, Suite 522

Washington, DC 20006.

tel. (202) 466-8191

fax. (202) 466-8189.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Allison Akana |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Myra Polinger |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| International Advisory Board |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Maya Escudero — USA/Philippines |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| Pam Zinkin — England |

| Maria Zuniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| Trude Bock — Editing |

| Alicia Brelsford — Art & Layout |

| David Werner — Writing |

| Jason Weston — Technical |