Sick of Violence: The Challenge For Child-to-Child in South Africa

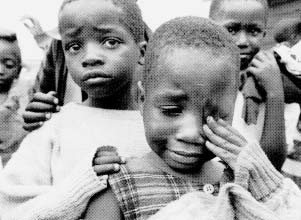

In January, 1996 three health educators from the Americas—Martín Reyes, Maria Zuniga and David Werner—went to Cape Town, South Africa to facilitate a Child-to-Child training-of-trainers course. Called “Participatory Methods of School Health Education,” this intensive oneweek course was part of the new Summer School Community Health Program at the University of the Western Cape. The Summer School is directed by Dr. David Sanders (co-author of our new book, Questioning the Solution.)

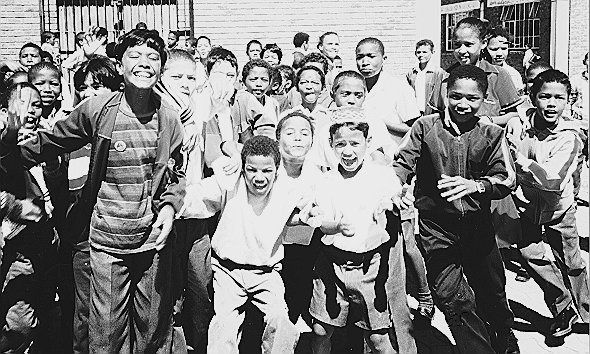

During the course we worked and played with a group of 32 adults and 21 school children. To bring three dozen primary school kids from a low-income resettlement area into the hallowed halls of a South African University was a jolt to many course participants. But Martín Reyes—who for years has been a roving Child-to-Child pedagogue throughout Latin America—is emphatic that when Child-to-Child methodology is introduced to a group of adults, it is essential that local children take active part. How can one learn participatory methods with children unless children participate as equals? Young and old contribute their perspectives and everyone learns from each other.

The adults in the Cape Town course (mostly community nurses, social workers, educators, and school teachers) were amazed, and in the end delighted, to actually work and learn together with children about problems that the children themselves defined. In spite of some challenging and worrisome concerns, all agreed that the course was a real eyeopener. And fun! Adults learned to listen to children and respect their problem solving abilities. And children, who were initially terrified to speak out, gained confidence in expressing themselves candidly among attentive adults. We feel confident that in their respective schools and communities, many course participants will introduce Child-to-Child in a discovery-based, empowering way.

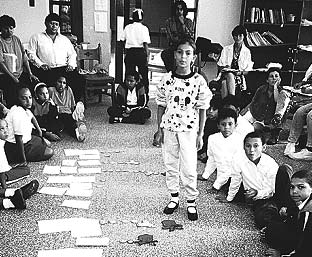

Children’s community diagnosis In this learner-centered Child-to-Child approach in Cape Town, the children started with their own ‘community diagnosis.’ Through learning games that included even the shyest children, they drew pictures and listed what they saw as the biggest problems affecting their own and their families health and lives. After they had listed their problems, the children used small cut-out figures (faces, skulls, arrows) to analyze which problems were most important in their community, and how they interrelated.

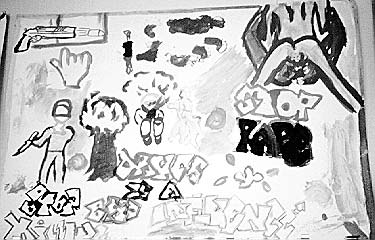

The results of the children’s community diagnosis were deeply disturbing. Heading their list of “Problems Affecting Health” they put concerns such as Gangsters, Gun-shooting, Fighting in the Home and Street, Theft, Drug Use, Glue Sniffing, Drunkenness, Parents Fighting, Beating-up Children, and Rape. Even such wide-spread, underlying problems as “Not Enough Money” and “Empty Plate” (hunger) ranked second to the children’s concerns related to violence.

To our amazement, even the nurses and health workers, who we expected to focus on biomedical ills (diarrhea, undernutrition, etc.), also put violence as the biggest danger to children’s well-being. All agreed that “Violence is a national crisis.”

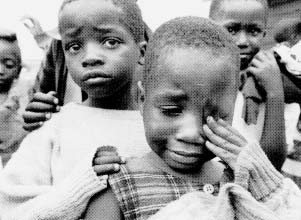

Paradoxically, especially in poor townships, violence in South Africa has increased since the official end of apartheid. This may in part be because repressive security measures have been lifted, yet abject poverty still abounds. The huge inequalities entrenched during the era of colonial rule are still largely in place and can only slowly be corrected. The millions who are homeless and jobless are understandably impatient. Violence is the barometer of inequity. Change in South Africa has only just begun. And children, more than most, continue to suffer.

Clearly, when school children identify violence as their biggest health-related problem, this adds a difficult new dimension to Child-to-Child. In the Cape Town workshop, participants grappled for possible solutions, or at least ways to cope with this overwhelming reality. “But what can the children do?”

Obviously, children alone cannot halt violence in their communities. Indeed, the adults were concerned that such a monstrous problem was a focus of discussion with school children. But, as Martín pointed out, it was the children who voiced concern Vulnerable as they were, they wanted to explore ways to respond. Indeed, one benefit from the course was to help the children to talk more openly about violence in their homes and neighborhoods, and to look for ways where they could take positive and relatively danger free-action.

The children proposed several actions they could take. To help keep ‘high risk’ youngsters from joining violent gangs, they had the idea of forming clubs or groups that do fun things, that get a kick out of helping people, not hurting them. They also suggested that they make a special effort to befriend children who are angry, sullen, abandoned, or mistreated. These are the children that tend to join street gangs and turn to crime and violence. They recalled one little boy, a loner who often came to school bruised and beaten. By age 10 he had joined a gang and killed a shop keeper in a robbery. “He seemed so mean and angry,” commented the children. “But maybe if we had tried to befriend him, talked with him about his difficulties, invited him to our after-school games” They talked about befriending some of the street children, the little ones whose homes are broken, whose parents can’t find work, or “who steal because their plates are empty.”

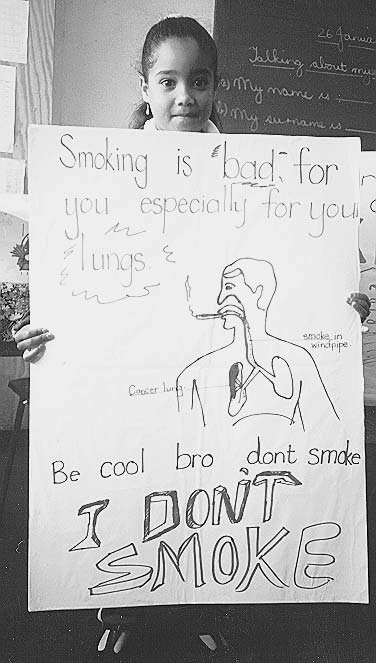

The last day of the Child-to-Child course, the children returned to their school where they led activities in 5 different classrooms, presenting ideas, actions, games, posters, songs and skits they had designed around their identified concerns. Where possible they tried to be optimistic, hopeful, to look for ways to make their lives and communities better by taking helpful, positive action:

In one classroom children acted out a variety of socially positive jobs or careers everything from “health worker” to “bread maker”—which children could aspire to and take pride in, rather than to hero-worship gangsters (which they frequently do).

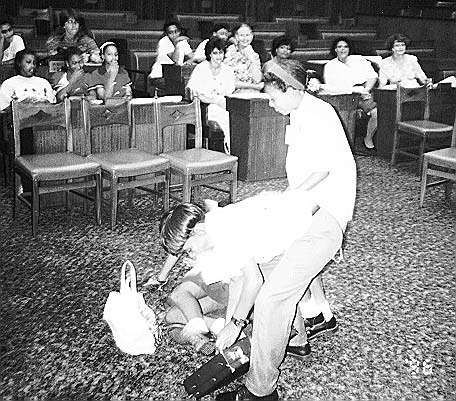

In another classroom, children acted out a skit showing a young gangster (gang member) attacking and robbing a woman. A good policeman’ arrests and jails the gangster, but then talks to him about why he robbed the women. “Because I was hungry,” answers the gangster. The policeman shows concern and the gangster expresses regret. In the end, the policeman releases the gangster so that he can be with the girl he left pregnant while she gives birth. (To give birth, the girl actor pulls out a doll from under her blouse.) In the end the gangster, removing his dark glasses, takes responsibility for the baby. Lovingly, the boy cradles the doll in his arms. This breaking of the stereo typed roll models brought shrieks of nervous laughter from the pupils. But the skit provoked intense discussion about new and healthier, more caring alternatives.

In yet another skit, a young boy, standing in an improvised ‘Parliament’ behind the national flag of the ANC, acted the roll of President Nelson Mandela. The child impersonated his manner and voice so exactly that everyone chuckled. Paraphrasing Mandela, he told the audience, “Today in the New South Africa our destiny is in our own hands. Each of us is free to become what we want, to pursue our own dreams, to join together in building a better world… for all of us!”

What was most wonderful in these activities was that, in spite of the violence which threatens their health and their lives, the children were able to look for and begin to chart a way forward, by working and playing together. Their youthful quest for a way beyond violence was an echo of their nation’s struggle to move beyond apartheid toward a fairer, more equitable and truly human society. They have a dream.

It was apparent that the discovery-based, participatory approach to children’s education can help nurture the collective self-determination needed for building that dream.

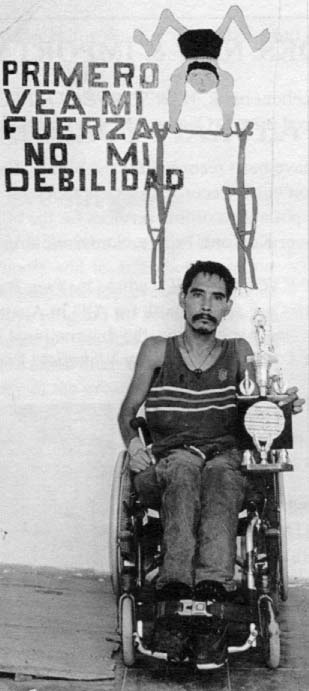

From Village Health Worker to International Child-to-Child Guru, and still a Village Health Worker at Heart: Martin Reyes Makes Good

To those readers who have read our Newsletters over the decades, Martín Reyes is a familiar name. Thirty-one years ago Martín, then a 14 year old village boy with very little formal schooling, began hanging around the Clínica de Ajoya. First he came out of curiosity, later to help out however he could. Eventually Martín became a very caring and capable promotor de salud (village health worker), then a leader of Project Piaxtla, the primary health care program from which grew the books Where There Is No Doctor and Helping Health Workers Learn. For several years Martín was also an advisor to PROJIMO, the community rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers.

Martín’s role in the evolution of Child-to-Child. In the early 1980s Martín, together with David Werner, was deeply involved in developing the concept and practice of Child-to-Child. Martín has since become an international promoter of what he calls a ’liberating’ approach to Child-to-Child. The methodology he fosters recalls that of the Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Its aim is to enable school-aged children to define their own health problems, analyze causes, and take collective self-determined action to protect the health of themselves, their families, and communities.

We should explain that Child-to-Child began with more conventional methods, using exciting games, songs, role-plays and recipe-like ‘activity sheets’ to teach school-aged children ways to prevent and treat common maladies. The goal was (and in part still is) to hel them to meet the health needs of their younger brothers and sisters.

Little by little, however, Child-to-Child has been evolving from a prescriptive program to a child-empowering open-ended process. Its vision has become more transformative: HEALTHY CHILDREN IN A BETTER WORLD. Only when young people begin to make their own observations, draw their own conclusions, and stop obediently memorizing what they are told, is there hope for engendering effective participatory democracy: the key to fairer, healthier societies. Child-to-Child as Martín promotes it is part of this larger vision. It is founded on a deep respect for children’s own cooperative problem solving capacity.

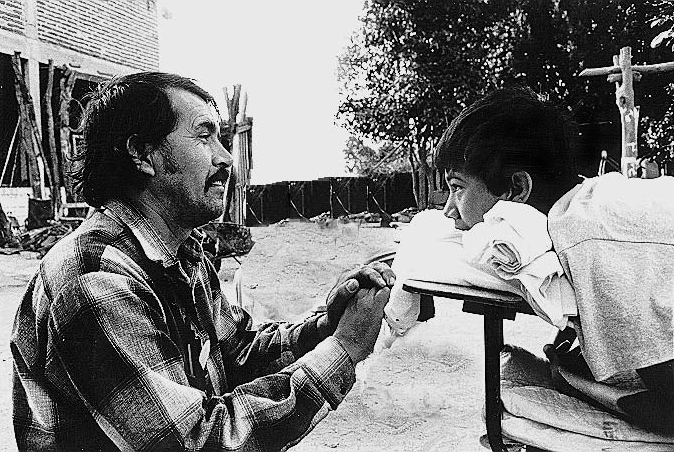

In 1993 Martín was awarded a prestigious Ashoka International Fellowship to promote his liberating concept of Child-to-Child throughout Latin America. This he has done admirably. I (David Werner) have had the privilege to work with Martin in facilitating regional Child-to-Child workshops in Mexico, Nicaragua, and recently in South Africa and Bolivia. In Bolivia, where we visited in April 1996, 19 different non-government programs are currently promoting Child-to-Child as a result of Martín’s inspiring workshops during former visits. In Cochabamba we met with children who are promoting Child-to-Child in different towns, and we were deeply moved by their presentations. One girl told how a group of children who were being cruelly mistreated by school authorities organized, collectively confronted the authorities, and won better treatment and respect. As he hugged the girl, Martín said, “Congratulations! This is what Child-to-Child is about!”

Martín’s international Child-to-Child work is currently coordinated by CISAS in Nicaragua. Groups from many countries request Martín to lead regional training workshops. He agrees as his time permits, provided that th groups guarantee that local children will take part in the workshops and play an active and decisive role.

Altogether, it is an exciting and potentially revolutionary process. For me it is especially pleasing to see a villager with very limited formal education but with a wealth of practical community experience gain international recognition and esteem. With a few more Martíns, health and education policies might be geared more to the common people’s most pressing needs. Vulnerable groups might cease to be targets and become archers.

Theme of a Meeting of the International People’s Health Council, Cape Town, January 1996: South Africa In Transition: Will the End of Apartheid Make Way for Social Justice?

Confronting Persistent Violence of Poverty.

South Africa is struggling through a difficult transition. With Nelson Mandela at the helm, millions of people long inured to poverty and oppression look forward to a new society that gives those on the bottom a fairer chance. The police state has ended. Political prisoners have been freed. But many of the injustices and inequities of the past persist. The 15% of the population that is white still owns 80% of the land. One of six South Africans lacks housing. Black unemployment is around 50%. Although acute malnutrition in children is low (2%), 35% of children are stunted due to chronic undernutrition. Despite the new government’s allocation of $9 billion for education, 50% of people remain illiterate. In poor townships violence and crime are escalating out of control. People are growing impatient for promised changes. There is a swelling debate as to where South Africa is headed.

In January 1996 a small international group from the International People’s Health Council (IPHC) together with representatives from South Africa’s progressive health movement participated in an all-day workshop in Cape Town. The purpose was to place the current transition in South Africa within a global context. It became clear that different and conflicting forces are at work to shape the future of South Africa, both from within the country and beyond.

In 1994, the Mandela government launched an ambitious Reconstruction and Development Program to address the urgent social needs, especially for housing, education, health care, and employment. But the government is caught between responding topeople’s basic needs and to powerful pressure from the elite, both domestic and foreign. The International Financial Institutions (World Bank, IMF, etc.) insist on the privatization of government enterprises, including hospitals, thus increasing the loss of jobs. Progressive taxes (where the rich pay a much higher percentage) are being challenged, while non-progressive taxes (value added taxes or sales taxes on purchase of goods) are being increased.

Under such pressure, the ANC coalition government is having trouble meeting the common people’s enormous needs and demands. All in all, the government has done little to move toward the redistribution of income and wealth desired by many of its supporters. Angered by the slow pace of economic reform, the 1.6 million member Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) called a selective work stoppage on December 19, 1995 and another in January, 1996.

At the recent IPHC meeting in Cape Town, participants felt that it is currently extremely important that socially progressive movements maintain a strong position, independent from government. They stated that organized pressure from below is essential to keep even the popular, elected government accountable and responsive to the needs of the population. The evolution of the new South Africa is at a watershed. If those who have struggled for a more just society are to realize their dream, now is the time to make a united stand.

Under the previous, oppressive regime, the progressive health movement was strongly united in its stand against apartheid. The “enemy” was clearly defined. But since the democratic ANC government took power, the progressive movement has become fragmented and to some extent lost the clarity of its course. Today things are less clear. As in Zimbabwe after the overthrow of colonial rule, a new black elite is in part replacing the white elite. Harsh inequalities remain.

Everyone agreed that now is the time when a coalition of progressive groups can still have an important influence on helping the country’s more idealistic leaders take a course of people-centered development. At the January meeting there was an enthusiastic move in this direction.

A Timely Quote

“If we truly believe that the right to food is the right to life, then this right should supersede other secondary rights, including the right of corporations to profit in the presence of hunger or famine. Similarly, the right of landless farmers to cultivate idle land to feed their starving families must supersede the property rights of the persons or corporations that may own that land. Imagine the agony of the landless worker peering over her neighbor’s fence, and seeing vast tracts of idle land to which she has no access.”

—Tony Quizon, Executive Director of the Asian NGO Coalition at the 1995 NGO Workshop in Quebec, in preparation for the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome.

The Rapid Spread of AIDS in South Africa

AIDS in South Africa is spreading faster than elsewhere on the continent. and is having a devastating impact on people’s health and lives. Currently, the incidence of AIDS doubles every 12 or 13 months! Anonymous blood testing shows that one in 10 pregnant women in South Africa is HIV positive. The Mandela government has given AIDS prevention high priority. Yet campaigns to promote safe sex through condoms have had meager results. Most men refuse to use condoms. A sex worker who insists on using condoms is paid 1/10 as much as the sex worker who doesn’t.

Currently it is estimated that one in ten persons in South Africa is HIV POSITIVE.

Transmission of HIV in South Africa is mostly heterosexual. Since HIV passes more readily from men to women than from women to men, more women than men are infected. Many women fall ill with AIDS in their early 20s, having contracted the virus in their teens.

The rising death rate from AIDS will have a far-reaching effect on society. Educational and care-providing services will be hit especially severely since most nurses and school teachers are women.

The impact on children will be devastating. Already in some provinces recent gains made through Child Survival campaigns have been reversed because of AIDS. One of three babies born to HIV positive mothers contracts HIV and will die in a few years after prolonged illness, chronic diarrhea, and weight loss. Also, millions of children will be orphaned. Currently, NGO’s (non-government organizations) are trying to provide for AIDS-orphans, but NGO’s will probably be unable to cope with the growing numbers.

Paradoxically, some social scientists predict that the escalating AIDS disaster may spur a radical restructuring of society, with a return to the extended family and communal living. They suggest that the current high rates of youth violence and membership in gangs is in part a consequence of the dysfunction of the nuclear family. In the ‘modern’ nuclear family, introduced by the white ruling class, children are often left alone for long periods while both parents work (or look for work). There is a loss of community and peer support. Single mothers abound Lost to a large extent is the social fabric of caring and sharing of traditional African village structure, which provided a supportive communal environment for children. In the old days, several related families lived in a circle of huts and shared resources, food, child care, and other responsibilities with one another, like one big close-knit family.

The roots of such communal living run deep. Social scientists predict that the AIDS pandemic may, in the long run, forge the way toward a more caring and humane social order, one in which cooperation and basic needs are more important than competition and economic growth. Nevertheless the human suffering from the AIDS pandemic—with so much protracted sickness and death—will be tremendous.

Research and education campaigns are being conducted to slow the spread of HIV. The national Medical Research Council has been conducting a study with more than 2000 sex workers in truck-stops between Johannesburg and Durban. Because men resist condoms, there is need for an invisible safeguard against HIV, that can be controlled by the women. Trials are underway to determine the safety and effectiveness of a topical viricidal agent called N-9 that can be sprayed into the vagina. The thin coating of N-9 reduces the spread of HIV, both from man to woman and from woman to man. A new preparation with a biological adhering agent is said to provide protection for up to 24 hours.

Such technologies may be helpful. But sooner or later South Africa—like the rest of the world—will need to face the fact that technological fixes are not sufficient to cope with AIDS and other monumental problems whose roots are social and political. The spread of AIDS, like the growing violence, is linked to extreme poverty and gross inequality between classes, races, and gender.

The only long-term solution to the crises of our times will come through redistribution of resources, wealth, and power. The new South Africa—with the leadership of Nelson Mandela, and with a strong popular base born from the long struggle for racial equality—is in a better position than many countries to oppose the dehumanizing market-friendly model of development. It has the opportunity to embrace a model of development based on equity, which favors the needy before the greedy. It has the possibility to build a caring society which strives for the well-being of all through cooperation, rather than the prosperity of a select few through competition. In today’s troubled world such an alternative is sorely needed.

Achieving such a people-friendly alternative for development will not be easy. The globalized market is not kind to nations that put human need before economic growth. If South Africa is to succeed in turning the tide toward a more egalitarian paradigm of development, it will need support from a coalition of progressive grassroots movements around the world.

With this goal of building global solidarity from below, the International People’s Health Council in cooperation with the progressive health movement of South Africa will hold the IPHC’s 3rd International Meeting in Cape Town, January 1997. If you support the goal of a fairer, more sustainable world, consider coming. Or contribute toward making the meeting a success.

The Globalization of Violence

In the lead article of this Newsletter we discuss the impact of growing violence on children’s lives, as described by school children in South Africa in their ‘community diagnosis’ with Child-to-Child.

Another country where children place strong emphasis on violence when diagnosing their day to day problems is the USA. For the last several years, Celine Woznica—a health educator who has worked for years with Martín Reyes—has been facilitating Child-to-Child in low-income neighborhoods of Chicago. Celine was startled when the children in Chicago, like the Cape Town children, put violence, crime, drug use, and mistreatment by adults (including parents and police) as the biggest problems affecting their well-being.

But South Africa and the USA have certain preconditions in common. Both have a brutal record of class and racial inequality. Violence begets violence. And the crisis of growing violence is global. As the gap between rich and poor widens world-wide, violence an crime increasingly threaten children’s wellbeing in many countries, especially in urban areas. Child-to-Child facilitators in Latin America noted this disturbing trend. It is especially acute in Nicaragua where poverty is escalating and unemployment has reached 70%. Even in Bolivia where indigenous populations tend to be traditionally peaceful, violence and crime are becoming enormous problems. This is a reflection of extreme poverty and widening discrepancy between rich and poor. While the privileged live in splendor, millions grovel under conditions of increasing unemployment and declining real wages. Today in Bolivia, a family of 5 needs 7 minimum wages simply to meet its basic food needs. It’s a small wonder that crime rates are high. And in Brazil, where the income gap is the highest in Latin Americas, more than 5 million hungry children live on the streets, where local businessmen sometimes pay police to brutalize or kill them.

In Argentina, where I (David Werner) was invited to speak at the 3rd National Meeting of Social Pediatrics in April, 1996, one speaker showed graphs showing health trends among children since the 1980s. While there has been a steady decline in deaths caused by infectious diseases (due in part to campaigns for immunization and oral rehydration), the death rate from accidents, and especially from violence, have climbed steeply. The speaker asserted that the startling increase in violence was a consequence of pervasive social problems, especially growing inequity, increased unemployment, and declining real wages. He concluded that new indicators for measuring well-being and development are needed. Child mortality and survival statistics are misleading. Technological interventions may lead to lowering of child death rates, but this says little about the quality of life of those who survive.

In the United States infant and maternal mortality rates may be low compared to many Third World countries. But they are the highest of the so-called “Northern Market Economies.” However, mortality rates tell us little about the quality of life of the children and youth who survive. A national survey several years ago showed that in the USA, 20% of teenage boys and 10% of girls attempt suicide! Also, the homicide rate in the USA is much higher than in any other economically prosperous country, as is the proportion of the population that lacks any form of health insurance (15%). In the USA one in four children lives below the poverty line. Yet the Contract with America has gutted one social assistance program after another, from Head Start to child support for unemployed single mothers. Over the past 10 years real wages of the working class have declined while earnings of the very rich have skyrocketed. Taxes have increased for the poor, as have tax breaks for the rich.

Social activists describe this kind of entrenched and growing inequity structural violence. Structural violence leads to personal violence, at every level of society, but especially among-and toward-those who are most marginalized and desperate.

If children's health is a concern, we must start by helping to free their minds.

Unfortunately, the United States (or better said, US government and big business) have great influence over political and economic trends worldwide. The same sort of cutbacks of public spending, decrease in real wages, and flattening of taxes that were formerly progressive (which used to help equalize gains and services across the classes) have been imposed on poor, debt-stricken countries in the form of Structural Adjustment Programs.

One key aspect of Structural Adjustment, as required by the World Bank and IMF in exchange for bail-out loans, is the privatization of government enterprises and public services. True, the selling of such enterprises provides governments with money to service foreign debt. But it also causes massive unemployment at the same time it reduces public assistance to the destitute. In each of the countries of Latin America I have visited in the past year—Mexico, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, and Argentina—popular demonstrations were taking place to protest the privatization of different public enterprises and services, ranging from mining operations to telephone services to public hospitals. The protests were mostly organized by the thousands of employees who were losing their jobs. Their protests went unheeded, excepts for violent repression by police and soldiers. ‘Progress’ and ‘development’ have been defined as ’economic growth’ which, of course, means growth for the already wealthy. And who are the poor to stand in the way of ‘progress?’

Following this fat-cat paradigm of ‘development,’ in which economic growth is seen as the ultimate measure of well-being regardless of the human and environmental costs, we are headed on a disaster course. It is time that more of us wake up. If children’s health is a concern, we must start by helping to free children’s minds. Today’s children will be tomorrow’s leaders or beasts of burden, depending on how we educate them.

This is why Martín Reyes’ “education of liberation” is of such vital importance.

Need for a Total Ban on Landmines

Profiteering in Violence Against Women and Children.

UNICEF’s 1996 State of the World’s Children report deplores the many forms of violence against children, especially the violence of poverty and of war. It states that “Wars and civil conflicts are taking a massive toll of children approximately 2 million children have been killed during the last decade, and between 4 million and five million disabled. Twelve million more have been uprooted from their homes, and countless others face the risk of disease and malnutrition and separation from their families.”

Among other crucial measures, UNICEF calls for an international ban on the manufacture, sale, and use of landmines. Since 1975 landmines have maimed or killed more than a million people, and the majority have been civilian women and children. And the devastation continues. According to UNICEF, “In 64 countries around the world, there are an estimated 110 million landmines still lodged in the ground-waiting. They remain active for decades.”

UNICEF, health rights activists, and a few daring congress-persons have requested the US government to ban landmines. The response of the White House-in an election year-has been anything but heartening. In considering the ban, President Clinton, like most of his colleagues in both major parties, puts powerful lobbies and bargaining for votes before the health and lives of those who can not or do not vote (children, aliens, the disaffected majority). He is therefore in the process of negotiating a weak agreement: a ban that is a non-ban. In essence, he says, the US will ban anti-personnel landmines except when it finds it useful or necessary to use them!

No one claims that anti-personnel landmines are essential or even important to US military operations. But the weapons industry has a powerful lobby. So does the Pentagon. And as every presidential and congressional candidate knows, you can’t win an election without selling your soul to the company store… at least not as long as voters (and potential voters) remain socio-politically anesthetized. It is time that we wake up and act!

What You Can Do to Stop Landmines

-

Do not tolerate the proposed wishy-washy US government agreement on landmines. It places the interests of the arms industry (and its powerful lobby) before the safety and rights of children.

-

Write or fax a protest letter to your congress-persons and to the President. Express your outrage and demand a total ban on anti-personnel landmines. Over 30 nations now enforce such a ban. But many key nations, including England and France do not. Yet if the US approves a total ban, England, France, and other nations will probably follow suit.

-

Educate: Make family members, friends, colleagues, and neighbors aware of this brutal issue. Encourage them to protest the deadly proposed US policy on landmines.

-

Write informative letters to the editor of your local news paper. Try to create awareness launching protest through radio and TV talk-shows, etc.

-

Vote only for candidates that support a total ban on landmines-and let your reasons be known.

Hundreds of thousands of children and non-combatant adults will continue to have their limbs blown off, only to make arms producers richerunless we take prompt action.

CITIZEN ACTION, WHEN STRONG ENOUGH, CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.

Sanctions in Iraq: A Crime Against Humanity

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has reported that, because of the prolonged sanctions against Iraq, more than 1 million people, most of them children, have died. From 1990 to 1995, the mortality rate for children under five increased six times over prewar levels. Today, more than 4 million people are starving to death, and life expectancy has plummeted by about 15 years! Former attorney general Ramsey Clark calls the blockade “a crime against humanity…a weapon of mass destruction [that] attacks women and children…like the neutron bomb it takes lives, it kills people, but it protects property.” Please contact your elected representatives and let them know how you feel.

An excellent new book titled The Children Are Dying: The Impact of the Sanctions on Iraq is now available. It includes the FAO report and other vital information. The cost is US$10.00. Order from the International Action Center, tel: 212-633-6646, fax: 212-633-2889, or write 39 W. 14 St. #206, New York NY 10011, USA.a

A Visit to Chile: To Help Launch a New Book on the Struggle for Health and Dignity

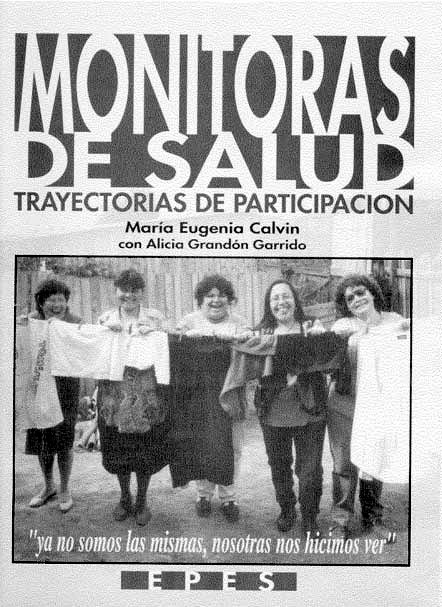

MONITORAS DE SALUD, TRAYECTORIAS DE PARTICIPACION Edited by Maria Eugenia Calvin with Alicia Grandón Garrido Available (Spanish only) through: Casilla EPES 360-11, Santiago, Chile—“We are no longer the same. We have made ourselves see.”

In November 1995 the progressive grassroots In November 1995, the progressive grassroots program EPES (Educación Popular enSalud; Popular Health Education) invited David Werner to Chile to exchange experiences and ideas. The occasion was the launching of a landmark book: Monitoras de Salud, Trayectorias de Participación (Community Health Workers: Actions through Participation). The book documents 10 years of people’s struggle for their health and rights in poblaciones (poor urban settlements) of Santiago and Concepción. Key actors are the monitoras, mainly mothers and housewives who, on learning basic preventive and promotive health skills through EPES, volunteer in the community health program.

For the monitoras—as for the community groups they mobilize—participation has been an enlightening, often liberating process. But it has also brought difficulties and dangers that emerge when oppressed people (especially women, who are often doubly oppressed) begin to organize and demand their rights. Realizing that health for all is inseparable from social equity in meeting basic needs, the monitoras help neighbors to analyze the root causes of their ills. Then they plan and take collective action to resolve common concerns and to work toward building healthier communities in a more fully democratic society. Win or lose, their united effort is empowering. In the words of two monitoras:

CLAUDIA: “I learned to face problems and to say what I want, also to ask questions … to know I can defend myself, open my mouth, learn that I am able.”

NADIA: “When I entered the group, I felt useless, that I was wasting my life. I felt insecure. I just let things happen, accepted them passively. This depressed me and was driving me mad … Entering the group permitted me to take decisions, decide things concerning my life. To participate has rejuvenated me, restored my self-confidence. I have recovered myself, my sleeping dreams.”

For me (DW) it was humbling to exchange experiences with the monitoras and staff of EPES. Deeply committed to the common good, they have long been social activists. During the dictatorship, many were harassed, tortured, jailed, or otherwise terrorized. Their stories are ones of uncrushable courage and commitment.

The beauty and power of Monitoras de Salud (the book) is that, in their own words, these women describe their experiences, their solidarity, their awakening. They reflect upon the personal and collective transformation they have realized through mutual struggle to solve local problems and—in the long run—to build a fairer, more caring society.

RAQUEL: “To change the country. To have a president who identifies with the poor, who is truly democratic, who doesn’t just say things will improve for the poor, but brings changes that are real… For changes that benefit us all we must have people who genuinely side with the poor… A good health system. We poor will be better off, and with more possibilities to work.”

Violation of rights before and after the dictatorship. In Santiago I was privileged to meet with the famed lawyer, Fabiola Letelier, who heads the Chilean Association for Human Rights, CODEPU. Fabiola is a sister of Orlando Letelier, the popular Chilean diplomat who was car-bombed in Washington DC in 1976. After a decade seeking justice, Fabiola has managed to convict two military chiefs of the former Pinochet government for their role in the assassination.

Fabiola Letelier told me that during the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990) the extent of human rights violations was incredible. In a nation of 12 million, one million people were tortured, jailed and/or assassinated. Another million fled into exile. It is distressing to think that this carnage was precipitated by a US government/CIA-supported coup that in 1993 toppled the socially progressive, democratically elected government of Salvador Allende.

Sadly, the end of the Pinochet dictatorship and return of national elections has not ended harsh socioeconomic injustice in Chile. Following World Bank recommendations, the post-Pinochet government has promoted an export-oriented, free market economy. Structural adjustment policies have favored foreign investment through tax breaks and other incentives, while further marginalizing the poor through lower real wages, higher sales taxes, and privatization of public services. Rapid economic growth (mostly benefitting the wealthy) has averaged 6% per year for the last 12 years, but at enormous human and environmental costs. As the economy has grown, so has the gap between rich and poor. Over 30% of the population now live in poverty. One million live in absolute destitution. Unemployment, homelessness, and crime rates have soared.

Meanwhile, forest, fish, and mineral reserves are being recklessly depleted. Pollution has reached crisis levels and is compromising the health of entire communities. In sum, the soalled “Chilean Miracle” has been achieved through devastating exploitation both of people and natural resources. Such a development model is both cruel and unsustainable. Yet the global powers uphold it as a great free-market success story.

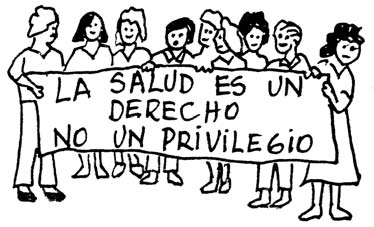

Change from below. In the face of deteriorating living standards, the monitoras bring together concerned groups to discuss common problems and take collective action. Poblaciones plagued by millions of rats have organized to clean up garbage areas. Others have pressured officials to provide water and sewage systems. Women have formed smal worker-run collectives to produce local crafts to sell informally. Others have organized cooperative day care centers, pre-school programs, and support groups for abused women and children. They have mounted campaigns to combat AIDS, to reduce the use of alcohol, drugs, tobacco, and infant formula, and to raise awareness of social and political determinants of health.

The monitoras recognize that a healthy society—one that defends the differences, health, and rights of all people—must be built from the bottom up through a united front of diverse disadvantaged and concerned groups.

SOLOMÉ: “We the marginalized, the slum dwellers, the professionals, the prostitutes, the homosexuals, the youth and children, all need to join together to change this country.”

The monitoras are aware that lasting improvement in their people’s health depends on the creation of fairer more equitable social structures. This, in turn, depends on a participatory process which strives for equality and mutual respect between men and women, between workers and employers, between disabled and non-disabled, between adults and children, between the strong and the weak. To this end, monitoras bring neighbors together to confront their difficulties and to improve their lives through problem solving cooperation.

The book Monitoras de Salud documents this dynamic grassroots process. It considers the struggle for health both in the immediacy of home and neighborhood improvement, and in the broader long-term context of the nation and the forces of globalization. It brings these larger issues to life though moving personal accounts by monitoras of their own lives, homes, communities, and world.

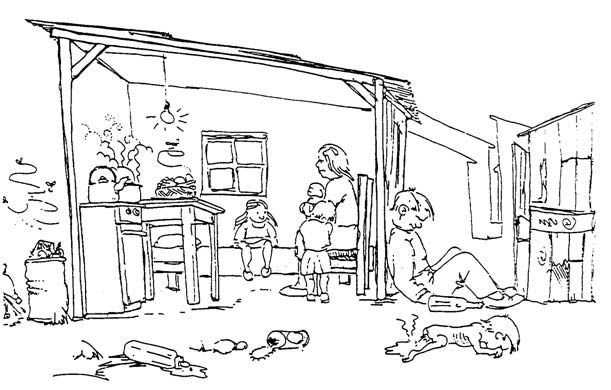

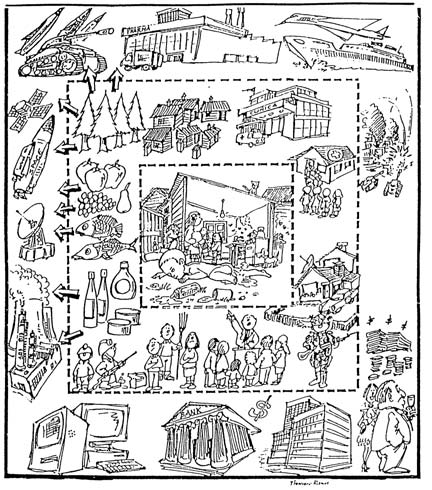

Learner-centered teaching methods. To help groups of women analyze the underlying causes of their hardships and poor health, EPES has developed excellent teaching materials. An example is the pair of drawings below.

|

|

|

Other Good Books Analyzing the Current Situation in Chile

Chile’s Free-Market Miracle: A Second Look, by Joe Collins and John Lear. 1995. The Institute for Food an Development Policy. ~~Available from Subterranean Company, Box 160, 265 South Fifth Street, Monroe, OR 97456, USA.~~

Democracy and Poverty in Chile: The Limited to Electoral Politics, by James Petras and Fernando Ignacio Leiva. 1994. Westview Press, Boulder CO, USA, and Oxford, UK.

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT): A Simple Life-Saving Technology—or Another Way of Exploiting the Poor?

After respiratory infections, diarrhea is the world’s biggest killer of children, draining the life out of 13 million youngsters each year. Diarrhea is especially dangerous to malnourished children, of whom there are more in the world today than ever before. The immediate cause of death from diarrhea is usually dehydration, or loss of fluids. Timely and effective fluid replacement (rehydration) can often prevent death. Some fluids are more effective than others. There has been much debate about which fluids are best to promote.

In the recent past the medical profession believed that the best way to rehydrate children with severe diarrhea was to use IV (intravenous) fluids. But such treatment is costly and requires skilled personnel. This makes the technology unavailable to millions of poor families. Then, in the 1960s during a massive cholera epidemic in Bangladesh, doctors lacked the trained personnel required to provide IV fluids to more than a small fraction to those who needed it; they tried giving by mouth the same sugar-and-salt solution used in the IVS. With this oral solution the death rate from cholera fell from over 30% to under 1%.

In 1978 the British Medical Journal Lancet declared Oral Rehydration Therapy as the most important medical breakthrough of the century.

The Evolution of Oral Reyhydration Therapy (ORT) at Project Piaxtla: Three Stories

Like many technologies, Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) can be either beneficial or counterproductive for disadvantaged people, depending on how it is introduced and who controls it.

The village health team of Project Piaxtla from the time it began 30 years ago-has learned this lesson the hard way, by trial and error. It has experienced both the life-saving potential of ORT and the risks of promoting it in a disempowering way. And the local health workers have made an effort to learn from their mistakes.

The following two true stories, taken from the early years of Project Piaxtla, illustrate both the potential and the pitfalls of promoting Oral Rehydration Therapy.

Story #1: The Needle and the Spoon

Back in 1974, a young French doctor, Mark Lallemont, volunteered for a few weeks at Project Piaxtla. Shortly before his return to Paris he told me (David Werner) the following story:

“Did I tell you how your village health worker, Martín Reyes, saved the life of a baby after I had failed?” Mark asked me.

“No,” I answered. “How?”

“It was a Sunday morning during the rainy season,” began the young doctor, “and unbelievably hot. I was alone in the Clínica de Ajoya when this young couple comes in with a sick baby, about a year old. They tell me his name is Filiberto and he’s had diarrhea and vomiting for 3 days. I saw the poor kid was dangerously dehydrated. His eyes were sunk and dry, and his skin was wrinkled like a prune. He hadn’t urinated since the day before.

“I told them the baby needed IV solution right away. But the worried father said he thought the baby was too weak to resist it. ‘It’s the one chance to save your baby’s life!’ I pleaded. At last the father gave in.

The mother held the whimpering baby while I tried to get a needle into a vein. You know how hard it is with a baby … and with the dehydration his veins were partly collapsed. I tried one vein after another. I was really sweating it. So were the parents. They kept begging me to stop hurting him, and just give up. His mother started to cry, which made me even more nervous. I realized that if I didn’t get liquid into the baby quickly, he would die. And for all I knew, his parents would blame me.”

The French doctor smiled nervously. “I tell you, I was really scared! In a big city hospital it’s different. You don’t have the parents as your assistants. You’re more insulated: you’ve got nurses, consultants, anesthesiologists and tons of equipment; you can avoid getting so close … You know what I mean?

“I decided the only way to get into a vein was to do a cutdown.” [make a small cut in the baby’s skin to expose the vein] Mark continued. “I explained to the parents what I was going to do and why. But his mother suddenly cried ‘NO! My baby has suffered enough!’ I tried to explain, but she snatched up her baby and ran out of the clinic. The father, before following her out, turned to me and said, ‘Thanks in any case. I guess we brought him too late.’ ‘Wait!’ I protested, “The baby can be saved!’ … But they were on their way out the door.”

The young doctor made a gesture of frustration and despair. “I felt angry and foolish. I thought of getting a court order, until I recalled where I was. Minutes later Martín came into the clinic with another sick person. When I told him what had just happened, he asked me to attend to the person, and ran out to look for the parents and dehydrated baby.

“Well,” Mark sighed, “It was the next morning before Martín next showed up. His eyes were red and he looked weary. ‘Is the baby dead yet?’ I asked.

“‘Not at all!’ said Martín with a big smile. ‘He still has runny shit, but he looks a whole lot better and has begun to take food. He is pissing often and sheds tears when he cries.’

“I couldn’t believe it. ‘You did a cutdown?’ I asked.

“Martín shook his head. ‘No, we spoon fed him liquid.’

“‘But didn’t he just vomit it up?’ I asked. ‘Oh, yes,’ Martín replied sleepily. ‘But each time he vomited we gave him more. We gave him a spoonful of water with sugar and a little salt in it every 3 or 4 minutes all afternoon and all night long.’

“‘You stayed with the family all night long?’

“‘All night. I learned a long time ago that when it’s a matter of life and death, and when a family is learning new skills, it’s safer if the health worker stays with them to make sure they keep it up. Most families traditionally give fluids to babies with diarrhea, but many simply don’t give enough. It takes a lot of reinforcement.’”

The French doctor paused and spread wide his hands expressively. “Voila! Little Filiberto survived … thanks to Martín and his patience and understanding.” He smiled at me. “So you see, a village health worker has taught this doctor something I never learned in medical school. In fact, he has taught me a lot.

Story #2: The Piaxtla Wonder Drug

Through its own mistakes, the Piaxtla health team has learned the harm that can come from medicalizing and mystifying Oral Rehydration Therapy. In its early years, the team made great efforts to get village families to accept ORT. To convince mothers to use it, they made some of the same mistakes UNICEF, WHO and international health campaigns have made and still make. They mystified and medicalized what is potentially a simple home solution. It happened like this:

When Piaxtla health workers began to promote ORT in the 1960s, mothers were reluctant to simply give their sick child a home-made drink made of common household ingredients (sugar, salt, and baking soda). They wanted real medicine. So the team tried to fool them. They packaged measured quantities of sugar, salt, and soda in little plastic bags, and added a pinch of red Kool-Aid to make it look medicinal. They promoted this mix as the Piaxtla Wonder Drug.

For the most part, acceptance was good. But soon the health team realized its deadly mistake. During the rainy season when more children get diarrhea, flooding rivers and slippery trails blocked access to health posts. Children died for lack of a simple ORT drink mothers could have made in their own homes. By leading people to believe they needed a “wonder drug,” health workers deprived them of that life-saving knowledge. In terms of its scientific formulation, their Wonder Drug was safe and effective. But within the geographic and social context in which they worked, it was dangerous. The dependency it promoted cost chil-dren’s lives. An alternative was needed that would place ORT technology in people’s hands.

Making the shift was not easy. But fortunately the program was still small and flexible. It had no big investment, economically or politically, in its misconceived “wonder drug.” Its aim was simply to help disadvantaged people meet their needs. So the health workers gathered courage and openly admitted to the villagers that their scheme for the ‘social marketing’ of ORT had backfired. They told people what was in the plastic bags and apologized for tricking them by adding the Kool-Aid. They taught people how to make effective rehydration drinks with common ingredients in their own homes.

Over the next few years the Piaxtla team developed hands-on, discovery-based learning methods and aids to demystify knowledge about dehydration and rehydration. They helped parents and children clearly understand why giving a kid with diarrhea plenty of drink and food is so important and why a simple homemade solution often works better than losing time and money by going a long way for unnecessary medicines—or commercial packets of sugar and salts that have been made to look like medicine.

For parents who can read and write—or whose children can—health workers made simple, illustrated sheets showing how to prepare and give a “special drink” for diarrhea in the home. These instructions were eventually included in the villagers’ health care handbook, Where There Is No Doctor. Other ORT-related teaching methods and aids-such as use of the Gourd Baby-are described in Helping Health Workers Learn.

Another mistake by Piaxtla: For years the Piaxtla team promoted salt and sugar home mix. Then they made another discovery. Researchers in Bangladesh and elsewhere had shown that ORT drinks made with rice or other starchy foods combat dehydration better than drinks made with sugar and salt (or with glucose and salt, as WHO prescribes though its commercial ORS packets ).

So the Piaxtla team made another big shift in its recommendations, placing the technology even more in the people’s hands. Traditionally in Mexico, as in many parts of the world, village mothers have used rice water and other cereal drinks to treat children’s diarrhea. Unaware of the value of such drinks, the Piaxtla team had followed the UNICEF-WHO guidelines, teaching mothers that sugar-based drinks work better. But now, the latest research confirms the value of traditional cereal drinks. ORT drinks made from rice powder, maize meal, or mashed potato can rehydrate a child more quickly and safely than do sugar-based solutions. So today Piaxtla’s health workers, build on the local traditions: they encourage mothers to treat diarrhea with rice or maize based drinks.

Most import of all, however, is to give the drink in large quantities, and also to give food as soon as the sick child will take it. (Food not only provides energy to fight the illness and prevent weight loss, but also speeds rehydration.)

The Piaxtla team uses the lessons learned from its mistakes to help people take a rational approach to ORT… and to rediscover the value of certain traditional forms of healing.

Promotion of ORT on an International Scale.

Throughout the Third World many community-based programs have come to conclusions similar to Project Piaxtla. They, too, try to demedicalize and demystify oral rehydration, to put technology in the people’s hands.

By contrast, most large government programs still promote ORT as a pre-packaged “medicine.” This they mystify, calling it “Oral Rehydration Salts” (ORS) or “electrolytes.” These are manufactured and distributed in silvery packets called “sachets.” Originally they were made available free in health centers. But as poor countries were increasingly pressured by the World Bank to slash health budgets, ORS production and distribution has largely been privatized. This combined pharmaceuticalization and commercialization of the ‘simple solution’ has led to an unnecessary dependency and needless expense for poorfamilies. It partly explains the continued high incidence of preventable death from diarrhea.

Promoting factory-produced ORS packets rather than teaching people to use effective home drinks creates dependency on a product that is often not available when needed. The following true story from Africa makes this tragically clear.

Story #3: A Deadly Solution for a Mother in Kenya

An instructor of health workers in a rural health program in Kenya, Africa, told me (David Werner) how she discovered it was better to teach people to make their own home drinks, rather than to depend on ORS packets. One day when she was visiting a rural health post, a young mother arrived, exhausted from the long walk in the scorching sun. On her back was a baby wrapped in a shawl. She had come on foot from an isolated hut five miles away. She said she had walked rapidly, because her baby was very ill with ‘running stomach.’ The mother begged the health worker for the life saving medicine in the silver envelope she had heard about on the radio.

But when the mother unwrapped her baby, she saw he was dead. His body was shriveled and eyes sunken from dehydration. The long trip in the hot sun had been too much for him.

“I felt partly responsible,” said the instructor. “If we had taught her to make a rehydration drink at home, instead of telling her she needed to come to the health post for a magic drug, her baby might still be alive…

“They tell us the packets are safer and more effective. But that’s nonsense!” grumbled the aging instructor. “What is safest is what will save the most lives. And that is what mothers can do easiest and fastest in their homes. In our circumstances a homemade drink is safer. If you ask me, ORS packets are downright dangerous!”

She looked at me piercingly. “What I mean is that makin folks believe that ORS packets are superior to what they can provide in their own homes is dangerous. And that’s exactly what the big government programs are doing. It’s what we did ourselves, until we learned the hard way. Do you understand what I mean?”

Why So Many Children Still Die from Diarrhea—A Search for More Appropriate Solutions

Scores of small community programs in many poor countries have chosen to promote homemade drinks while discouraging use of packets. But with the international Child Survival network churning out 400 million packets a year, it is an uphill battle.

Twelve million children continue to die every year. Their deaths are related to poverty and undernutrition, perpetuated by inequitable socio-economic structures. In spite of all the high level talk about “Health for All” and “Child Survival,” the rights of children are being systematically and cruelly denied on a massive scale. Yet global planners continue to put the profits of the powerful before the basic needs of the majority. The gap is growing between rich and poor, within countries and between them. Technological solutions such as ORT and immunization, while important measures, are no substitute for fairer social structures.

It is time to analyze the shortcomings of conventional health and development strategies and to look for new solutions, not only to reduce child deaths, but to work toward a sustainable global community where quality of life of all children is valued and fostered.

News and Updates from the Projects in Mexico

Project PROJIMO

Project PROJIMO, the community rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers in the foothills of western Mexico, has been increasingly active in recent months. A big boost—and a lot more hard but satisfying work for PROJIMO—has come through social worker DOLORES MESINA. Dolores has been a friend of PROJIMO for many years, having first gone there in childhood for orthopedic appliances and rehabilitation.

Dolores had polio in infancy. Among other difficulties, Dolores had developed an incapacitating spinal curve. PROJIMO arranged surgery (spinal-fusion) for her at Shriners Hospital in San Francisco. In spite of her disability (or perhaps, in part because of it), Dolores studied hard, continued her schooling, and eventually became a qualified social worker. Due to attitudinal and physical barriers, Dolores at first had a hard time getting a job. But she persisted banging on closed doors until they opened. Today she has a key position in DIF (Integral Family Development), a government advocacy program for disadvantaged children and families. Dolores’ job is helping to find solutions to the needs of disabled children, especially those in low-income or dysfunctional families. In this she coordinates closely with PROJIMO. Periodically she takes a bus-load of disabled children (and adults) to PROJIMO. There Mari and Conchita, who both have disabilities, evaluate their needs and provide orthopedic devices, assistive equipment, and wheelchairs designed and fitted to meet their individual needs.

GREAT NEED FOR WHEELCHAIRS

Unfortunately, DIF’s budget is quite limited, and with the growing economic crisis in Mexico, the needs are enormous. There are thousands of disabled people who are additionally handicapped because of lack of a decent wheelchair. The wheelchair building shop at PROJIMO meets a small fraction of the need.

HealthWrights in California collects donated used wheelchairs and looks for ways to take them to Mexico. David Werner, Trude Bock, and others ride one down every time they fly to Mexico.

HELP NEEDED: If you are planning to fly to Mazatlan, consider riding down with a wheelchair (and coming back without it).

Project PIAXTLA

A Village Health Worker Turned Eye Surgeon.

MIGUEL ANGEL ALVAREZ, a local village boy who 20 years ago became a community health worker, was helped by Project Piaxtla and its friends to continue schooling. Alternating village health promotion with continued study, eventually Miguel became a doctor. After helping to facilitate the village eye program for several years, he decided to pursue his dream of specializing in eye surgery. (He had assisted visiting volunteer eye doctors as a youthful health worker, and realized there were multitudes of blind persons too poor to afford sight-restoring surgery in the urban hospitals.) Now, having completed a post-graduate degree in ophthalmology in February, 1996, Miguel is back in Sinaloa with a renewed commitment to serve the people.

In May, 1996, Miguel spent a week at the Piaxtla clinic in Ajoya, where Roberto Fajardo of Project Piaxtla, and the PROJIMO team coordinated the notification and attendance of persons with eye problems from a wide area. Miguel provided advice and treatment for some, and planned surgery for others. The village of Ajoya is cooperating to repair and renovate the small surgery room at the back of the clinic. Enthusiasm is high. It is so refreshing when a local youth gets an outside professional degree, and then comes home to help people, rather than to exploit them.

HELP NEEDED: Sight-Restoring Instruments

Miguel Alvarez hopes to do a wide range of sight protecting and sight-restoring surgery at the village level, but desperately needs more instruments. If you know eye doctors who are retiring or uprading their instruments and may be able to make a donation (tax deductible) please contact us at HealthWrights. Our thanks to Dr. Rudy Bock and Dr. Lee Shahinian, ophthalmologists from the San Francisco Bay area, who have generously donated equipment for eye examination and surgery. OUR THANKS to many groups and persons for helping to support the work of HealthWrights, Piaxtla, and PROJIMO: Lytton Gardens Health Care Center, together with Nordstrom Rehabilitation Services in Palo Alto, CA for donating used wheelchairs, crutches, walkers, and other equipment to PROJIMO.

Physiotherapist Ann Hallum and massage therapist Marybetts Sinclair for volunteering to teach their skills at mini-courses in PROJIMO.

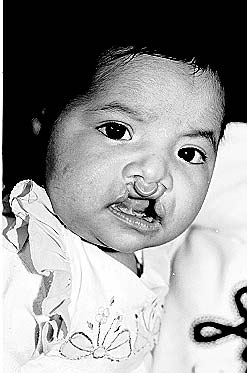

INTERPLAST in Palo Alto, California, and Shriners Hospital in San Francisco for continuing to provide essential surgery free of charge to disabled children from Mexico. In May, 1996 INTERPLAST very successully corrected the cleft lip of Sofia Peña. The 2-year-old came with her grandmother from Cosalá, the village where Martín Reyes lives and works with disabled (and non-disabled) kids.

|

|

|

Dr. Dennis Swigart at Rehabilitation Engineering Center of Palo Alto for helping medical student Nelly Chombo get a new hand after an accident with a meat grinder. She finds life and work easier with her attractive, functional prosthesis. We also thank Paul Trudeau and others at the center for frequent donations of second hand wheelchairs and orthopedic components.

The faculty and administration of San Simon University in Bolivia for awarding David Werner the post of honorary professor. (This University is restructuring its medical school curriculum to make it more community health oriented, and is launching a post-graduate degree for doctors in primary health care.)

We would especially like to thank two anonymous donors for donating a high quality scanner and an adapter for scanning color slides, to assist us in our desk-top publishing. This makes our work easier and improves quality. This newsletter was laid out making full use of this equipment for the graphics.

Books: New & Important

War Surgery. We are pleased to say that the excellent book, War Surgery Field Manual, which we announced in Newsletter #32, is available to non-profit Third World groups at reduced prices. Contact Third World Network. 228 Macalister Road, 10400 Penang, Malaysia.

Newsletters from the Sierra Madre have been recorded for the blind. Each of our last four newsletters (including this one, to be available soon) are available from HealthWrights on voice-recorded cassette tapes for use by blind persons, thanks to Action on Disability and Development (ADD). HELP NEEDED: For important recording services for the blind, ADD needs a new tape copier. If you can help in cash or kind, contact Sheila Salmon, ADD, 23 Lower Keyford, Frome, Somerset, BA11 4AP, UK. Fax. (01373) 452075.

Health for All: The South Australian Experience, edited by Fran Baum, is an excellent spectrum of writings on attempts to apply the international strategies of Primary Health Care and “Health for All” in Australia (which has its own Third World). Essential for all concerned with health policy, worldwide! (Francis Baum is active in the International People’s Health Council and taught in the Cape Town Summer School courses mentioned in the lead article.) Published 1995 by Wakefield Press, Box 2266, Kent Town, South Australia 5071.

Volver a Vivir; Return to Life by Suzanne Levine. Chardon Press, PO Box 11607, Berkeley CA 94721. US $18.00 including shipping. Discounts for bulk orders.

Suzanne, a young photographer who has a learning disability, has lovingly assembled a splendid series of photos of PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Mexican Youth), mostly in color. In this sensitive artistic booklet, disabled leaders and workers at PROJIMO speak from their hearts of their own experiences and work. They celebrate their discovery that they can live full, happy, productive lives after becoming substantially disabled. Through this warmly human view of PROJIMO, the author provides insight into the budding Third World Independent Living Movement as it merges with Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) in an empowering way. Highly recommended!

End Matter

In this issue we announce our new book: QUESTIONING THE SOLUTION: The Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival, with an in-depth critique of oral rehydration therapy. See page 13 and this newsletter’s insert.

| Board of Directors |

| Allison Akana |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Myra Polinger |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| International Advisory Board |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| Pam Zinkin — England |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| Trude Bock — Editing and Production |

| Renee Burgard — Design |

| David Werner — Writing and Illustrating |

| Jason Weston — Layout, Writing, and Online Edition |