Recreating PROJIMO to Meet Tougher Challenges

Friends who have read the Newsletter from the Sierra Madre for years are by now quite familiar with PROJIMO, the Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth in Western Mexico. Begun in 1981, PROJIMO grew out of Project Piaxtla, a villager-run health program started in 1964, based in the remote pueblo of Ajoya. Piaxtla and PROJIMO are best known internationally for the self-help manuals they gave birth to: Where There Is No Doctor (now in 83 languages), Helping Health Workers Learn, and Disabled Village Children. A new handbook that draws on the PROJIMO experience is Nothing About Us Without Us. Sample pages are included in this Newsletter.

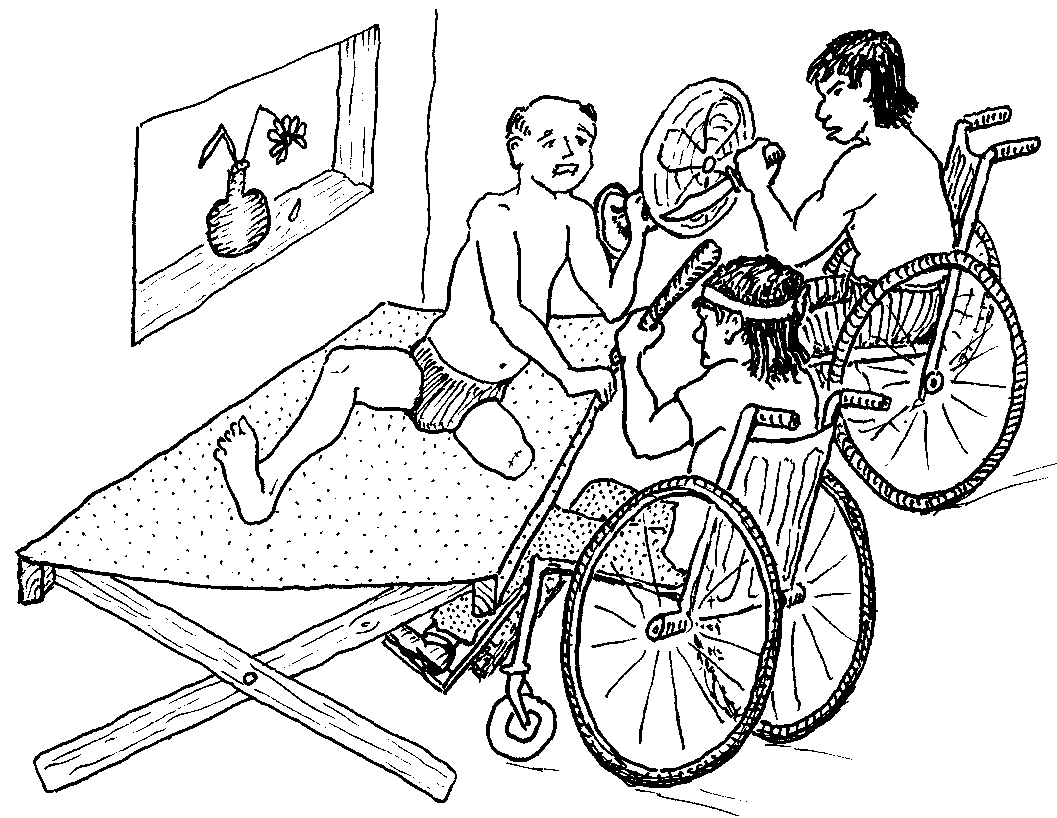

Over the years, PROJIMO—like most cooperative grassroots programs—has had its ups and downs. Some of the biggest advances have resulted from crises that threatened to close down the program. One early crisis, discussed in Newsletter # 25, involved an internal power struggle where the more extensively disabled, unpaid participants organized a revolt against the less extensively disabled, paid program leaders. The outcome was greater equality and more democratic management. A later crisis, also discussed in Newsletter #25, emerged from the growing number of youths disabled by gun-shot wounds, coming from Mexico’s fast-growing sub-culture of violence.

There followed a chaotic period of drug use and violence in PROJIMO. Man families were afraid to bring their disabled children. In the long run, however, some of the angriest, most violent street youth turned into creative and caring rehabilitation workers. (See below.)

The current crisis at PROJIMO —described in this issue—is also largely a consequence of the violence and crime that has swept across Mexico since the mid-1990s. For a time it looked like PROJIMO might cease to exist, and the program’s future is still uncertain. But exciting possibilities are emerging as the team of disabled workers attempts to adapt to the new, more difficult reality.

The growing crime and violence in Mexico has caused big problems at PROJIMO. One time two disabled street youth, high on alcohol and drugs, attacked an elderly diabetic schoolteacher. (For the full story, see our Newsletter #25.)

Recreating PROJIMO to Meet Tougher Challenges

This informative article is divided into 3 Parts. The first describes the growing wave of crime in the Sierra Madre, and its impact on the community rehabilitation program. The second analyzes the roots of increasing violence throughout Mexico (and world-wide). The third looks at ways PROJIMO is now struggling to respond to the present crisis. This response—which involves hard decisions and huge challenges—is still in its early stages. The team realizes it is a question of change or die.

PART 1: The Recent Wave of Crime, Kidnappings, and Violence in the Sierra Madre

Fear. Until recently the village of Ajoya, where PROJIMO is based, had about 1000 inhabitants. But in the last few years the village has shrunk to about 650 people as terrified families have moved elsewhere. The epidemic of violence—including holdups, assaults, kidnappings, rape of teenagers, and murder-for-money—has reached an unbearable level. More and more families, some of whom have lived in the village for generations, are abandoning their ancestral homes in search of safer (if not greener) pastures. Their exodus often involves substantial economic as well as emotional sacrifice.

For those who remain, the mood change in the village is profound. Not long ago on hot summer evenings folks sat on verandas and sidewalks outside their mud-brick houses: relaxing, chatting, strumming guitars. But today at sundown the streets quickly empty. Doors are bolted. Ajoya dawns the pall of a ghost-town. Even in daytime there is an aura of fear. Last year—after a rash of robberies and shootings on nearby roads and trails—at the end of the rainy season unharvested crops rotted in the fields because the owners of the better land-holdings were afraid to venture outside the village to pick them.

The current pattern of violence and crime has emerged in fits and starts over the past decade. But in the last 3 years it has spiraled out of control, with an increase in kidnappings and . sometimes (when ransom is not fully paid) brutal executions. Due to repeated hold-ups of trucks, the supply-line of goods from coastal cities—ranging from bottled gas to fish, vegetables and Coca Cola—has dwindled. Villagers, too, are reluctant to travel. Buses have often been stopped and passengers looted. Once, when the morning bus jumped a log placed across the narrow dirt road, the bandits fired after it, wounding two passengers. Last Spring, a bus driver was shot and killed. Because of repeated assaults, for a time the bus route higher into the mountains was discontinued.

There has been a Robin Hood-like pattern to the recent craze of thievery. Most of the kidnappers and bandits are disillusioned young men, some still in their teens. The targets of kidnappings, death threats and extortion are mainly wealthier families. But now, since most of the rich have moved elsewhere, sometimes families with just a few cattle, a village store, or modest savings are targeted. The livelihood of the poor is also affected. As affluent families move away—or sell their cattle to pay kidnappers—poor day-laborers who used to work for the rich often find themselves without jobs or income.

Kidnappings in and around Ajoya. For years Ajoya, like most towns in Mexico, has had a fairly high incidence of homicide. But most killings were related to family feuds, rivalry over a girl, or flare-ups of temper primed by alcohol. kidnappings and death-threats for money were unheard of. However, in the last 3 years, 9 persons have been kidnapped, with 6 related murders.

In September 1996 two young men were kidnapped at once. One was Julian Rios, whose family (until recently) owned many cattle. (The family had received several death threats to extort money, and Julian’s younger brother had been held up and shot several months before.) The other youth kidnapped was Marcelo Manjarrez 111, whose family was fairly wealthy until the grandfather, Marcelo Sr., was kidnapped 3 years ago. Marcelo Jr. had sold the family cattle to raise ransom money. But when he delivered incomplete payment at a remote spot in the mountains, the kidnappers killed both him and his father. Now, two years later, the 18-year-old grandson, Marcelo III, was kidnapped, together with Julian. Ransom was set at 500,000 pesos (about US$80,000) for Julian and 100,000 pesos for young Marcelo. Both families had to sell everything they had and to assign title of their homes to the bank to pay the ransom. But they managed to pay in full, and both young men were released relatively unharmed. The Manjarrezes fled town.

When it comes to dealing with back-woods bandits and kidnappers, the Mexican “law” (State Police, Federal Police, Federal Army, etc.) is often ineffective, or worse. Police told Julian’s father that for an under-the-table payment of 150,000 pesos they would hunt down and kill the kidnappers. But Julian’s father knew that such vengeance can trigger generations-long feuds and cause a chain of deaths in all families concerned. Wisely, he turned down the police’s offer, and let it be known that he had no ill will against the kidnappers’ families.

Vigilantes Add to the Killings. Until last year, families subjected to kidnappings or death threats usually did their best to pay the amounts asked, even if it left them paupers. But this has changed. In November, 1996, Enrique, the 20-year-old son of a village store-keeper, received a death threat with a demand for 50,000 pesos. Instead of paying, Enrique bought a sub-machine-gun (R-15). He and other young men from better-off families, together with a few young gunslingers known to be thieves, formed a group of vigilantes. When the next rich man, Melquiades, was kidnapped, the vigilantes pursued the kidnappers on mule back, ambushed them at night along the trail, and managed to rescue their elderly prisoner, unharmed but for bruises.

As so often happens, after the vigilantes took the law into their own hands, they have also committed abuses. Since colonial times, the local rich have scorned the poor families from further back in the mountains. They often blame the current disturbances on “those hillbillies” who have moved into Ajoya during the last decade or so. So the vigilantes decided to do a bit of ethnic cleansing. First they threatened some of the mountaineer families to leave town “or else.” Then, one evening last May, they fell upon 3 unarmed youth from such families and slaughtered them point blank. I (David Werner) was very close to one of these families. I spent the next several days helping them move out of town. The experience has been devastating for the family, especially for the younger children.)

Effect of the Crime Wave on PROJIMO

Those of us at PROJIMO have been deeply shaken by the recent kidnappings and violence. The homes of both the Manjarrez and Rios families were next door to PROJIMO. Both families have been very friendly. They have helped with construction and maintenance of the buildings, provided transportation in emergencies, and taken visiting families into their homes while their children were attended atPROJIMO. The school-aged sons and daughters of some families that have suffered kidnappings and killings have been active in the toy-making workshop and the “Playground for All Children.”

The growing wave of crime and kidnappings has seriously hurt PROJIMO in several ways:

A) Direct robbery. For several years, the CONOSUPO, a state-subsidized food store in Ajoya, has been managed by Margarita, disabled member of PROJIMO. A single mother, Margarita barely supports herself and her children with the 5% mark-up on the goods she sells. In the past 2 years her store was occasionally robbed. At night young thieves would break in through the tile roof and swipe a few bags of merchandise. Sh could recover from these losses in several weeks. The thievery was parasitic, not fatal. But then, one night this August, armed bandits arrived in a truck and stripped the store bare. It will take Margarita years to recover her losses. Fortunately, many villagers arc voluntarily helping her by adding a bit extra to the price of what they buy. Nevertheless Margarita is considering giving up the store and moving back to her parents’ town, where she would depend on their charity.

B) Local PROJIMO workers who leave town. The Children’s Toy-Making Shop has, also been affected by the lawlessness. In the village several teen-age girls have been taken by force and raped; the youngest was 11 years old. Also, some parents have receive notes threatening to rape their daughter, unless large payments were paid. Because of this situation, two teenage girls who had been doing a wonderful job teaching younger children in the toy-making shop were sent by their worried parents to stay with relatives in the city. Many other village girls have also been sent away.

C) Fewer people served—because of fear.

The most serious impact of the recent crime wave on PROJIMO is the fear it has caused. Families with disabled children in distant towns, when they hear about the lawlessness in the mountains, are reluctant to go to Ajoya. A few years ago PROJIMO often had as many as 50 disabled residents at any one time and attended an average of 5 or 6 new disabled persons a day. But in the past year, PROJIMO has had a core group of about 15 persons and has attended an average of only 3 or 4 new disabled persons per week. This reduction in persons served has raised serious questions about the continued existence of the village rehabilitation program.

D) Demoralization of the team. The PROJIMO team members are deeply concerned by the diminishing number of disabled persons who come to the village. Also, those who have families in Ajoya are worried about the impact of so much violence on their children. Although they are in little danger of kidnappings themselves (PROJIMO families are far from wealthy), their children observe the fear all around them, awaken to the rattle of machine-guns at night, and grow anxious themselves. The village no longer provides the tranquil climate that the team wants their children to grow up in. Several disabled workers have already moved away and others were considering doing so.

PART 2. Root Causes of the Crime Wave in Mexico and Elsewhere

Many factors lie behind the growing violence and crime in the village of Ajoya. Some are local and geographic. Others have to do with political and economic events at national and international levels. Contributing to the current pattern of violence is everything from drug trafficking to the increasing poverty, in part caused by global free-market policies.

Illegal drugs. One reason why Ajoya has more than its share of crime and violence is that the village, located at the foot of the Sierra Madre, is a strategic trading outpost. The small town is the link between two worlds, the point where the mule trails from the mountains meet the auto-roads from the coastal cities. As such, it is the crossroads between drug growers and drug traffickers.

For more than 3 decades, farming families in the Sierra Madre have grown opium poppy and marijuana, often in collusion with corrupt narcotics-control soldiers and police. (This devastating situation was discussed in Newsletter #18.) But until recently, the mountain people did not personally use the drugs they grew. They were cash crops that they could sell for much more than corn or beans.

But in the last few years, personal drug use by local mountain youth has skyrocketed. First, smoking of marijuana was introduced by young men who had gone to work as “wetbacks” in the USA, picked up the habit, and returned. ’ But today, cocaine is the most used recreational drug in the mountains.

Village health workers estimate that up to 70% of Ajoya’s adolescents have at least tried cocaine. Cocaine comes from South America and passes through Mexico on its way to the USA. Traffickers on their way north have discovered that a side trip into the Sierra Madre can be very profitable. Their strategy is seductively brutal. First they befriend the local youths and introduce them to the wonders of cocaine. Once the young folks are hooked, they swap cocaine for crude opium “gum” at an exchange rate that multiplies their earnings 10 fold when the drugs reach the USA.

With so many village youth hooked on cocaine, and with the cash to buy it harder and harder to get, many turn to crime for money to support their habit. Most of the young kidnappers and thieves are deep into drugs. For example, one night a young man who was stealing the stereo from my car fired a warning shot at me when I (foolishly) tried to stop him. An hour later, he tried to sell the stereo for a snort of perico (cocaine).

Increasing poverty. Other, more global factors have helped to precipitate the lawlessness in the mountain village. Ajoya is like an erupting boil on a sick human race. Crime and violence have been escalating at startling rate all over Mexico, as throughout Latin America and most of the Third World (and also in the United States). Crime and violence on the streets are symptomatic o institutionalized violence on a massive scale, of globalized crime against humanity.

Much of the increase in violence an crime world-wide can be traced to increase in poverty and hunger. The dominant model for “economic development,” designed to make the rich richer regardless of the human an environmental costs, has created a ever-widening gulf between rich an poor. Globally, economic productivity increases year by year. But wealthy concentrates in fewer and fewer hands Today, the world’s 470 billionaire have total earnings greater than those of the poorest half of humanity. Although more than enough food i produced to feed the whole of humanity well, today there are more hung children than ever before in history. International “free trade” agreements designed to favor multinational corporations, make weaker nations an peoples the slaves of a globalize economy based on greed, not on need.

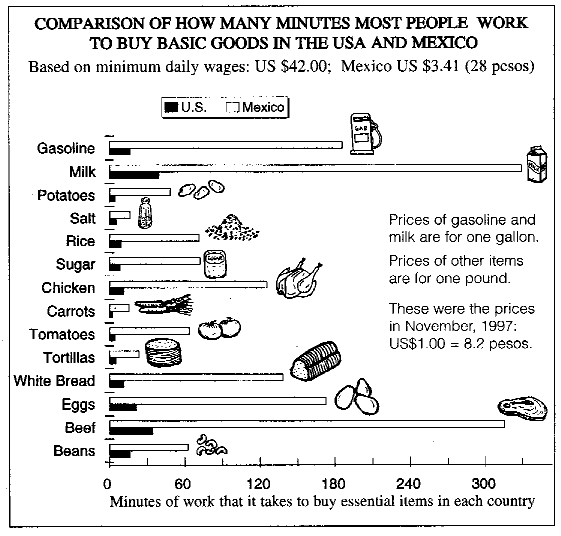

NAFTA and the globalized economy. It is no accident that the current socioeconomic crisis in Mexico—with its rapid rise in unemployment, wage cuts, drug trafficking, crime, and widespread despair—followed on the heels of the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Though NAFTA continues to be praised by the Clinton Administration in the USA, working people on both sides of the US border recognize that while a handful of big, multinational businesses have prospered, for the poor majority NAFTA has been devastating. Although Mexico today has more billionaires per capita than any other country, malnutrition and poverty are increasing. In preparation for NAFTA, the Mexican Constitution was changed, weakening agrarian reform laws that protected small farmers. (This was done so that big US agribusiness—consistent with “free trade”—could freely exploit cheap Mexican land and labor.) As a result, farmland in Mexico has again begun to concentrate into fewer hands, recalling the huge plantations of colonial times. In turn, over 2 million newly landless farmers have migrated to the growing city slums, where unemployment was already very high. Real wages of working people—already so low that poor families had difficulty adequately feeding their children—have dropped by 40% since NAFTA was introduced in January, 1994. And since the crash of the peso in 1995, thousands of small businesses and shops have gone bankrupt, causing even more unemployment.

Hopelessness of the young. In such a dire situation, many young people feel they have no future. A few years ago, motivated youth sought to continue their education. They dreamed of becoming professionals, or at least technicians, to achieve a reasonable standard of living. But today, the streets are full of jobless professionals. Doctors vend chewing gum and cigarettes, engineers dress as clowns to beg on street corners, lawyers blow flaming gasoline from their mouths in exchange for a pittance from affluent motorists. The gulf between the very wealthy and the common people has grown to levels that inevitably produce a spiral of anger, crime, and violence from below, and repressive measures of social control, increased corruption, and violence from above.

No wonder young villagers get discouraged and turn to crime! Their grandfathers fought a revolution to secure fair distribution of land, only to see the reforms they fought for shredded. The promise of higher education and jobs in the cities has gone up in smoke Safety nets for the poor, the sick and the hungry are systematically being dismantled Meanwhile, small, sputtering television sets—the one luxury even in cardboard huts—portray soap operas of the “good life” far beyond the reach of poor folks . . . unless of course, they violently rebel.

In today’s “free market” economy that favor the rich while making the poor redundant, the only option that many young people see to prosper is through crime. The gains of the Mexican Revolution, where peasants fought for fairer distribution of land and wealth, have been reversed by overwhelming forces of international dimension. Consequently, at a micro level, more and more young people are taking redistribution of wealth into their own hands through kidnapping and stealing from the rich. What other choices have they?

PART 3. PROJIMO’s Response to the Wave of Violence

Moving the Rehabilitation Activities to a Safer Village

As the numbers of disabled persons coming to PROJIMO from the coastal cities dropped to a bare minimum, the spirit of the team also fell. To stay in the village of Ajoya, they felt, was to slowly become a ghost program in a ghost town. What to do?

“Why not move to a village that is safer and more accessible to more people?” was a question repeatedly raised. The team began to explore possibilities. At last they decided to try moving to Coyotitán, a village of 2000 people about 40 miles from Ajoya, at the junction of the main north-south highway. Coyotitán (at least so far) has a lower incidence of crime and killings. Its location on the highway makes it easier to reach for families in coastal towns. Yet it is far enough from the cities to allow a buffer between the community program and urban rehab professionals, some of whom might make trouble for what they consider the “unprofessional” activities of disabled, unlicensed, village workers who have somehow convinced people that they do outstanding work.

First a small group from PROJIMO, led by Mari and Conchita, went to Coyotitán and met with disabled persons and their families. These people were eager to have PROJIMO set up a rehabilitation project in their town, and offered to cooperate in any way they could. The owner of a village store made a room in her home available for consultations until a more suitable place could be located.

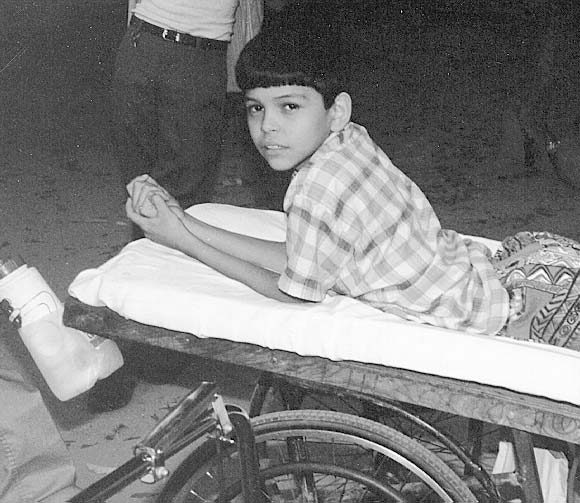

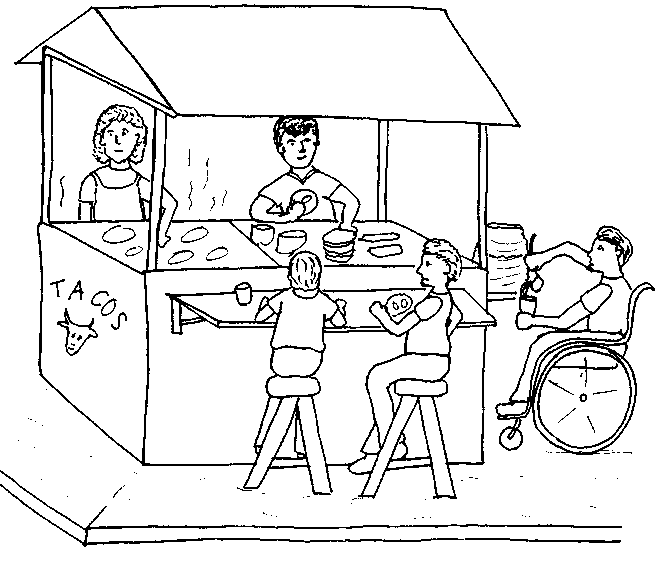

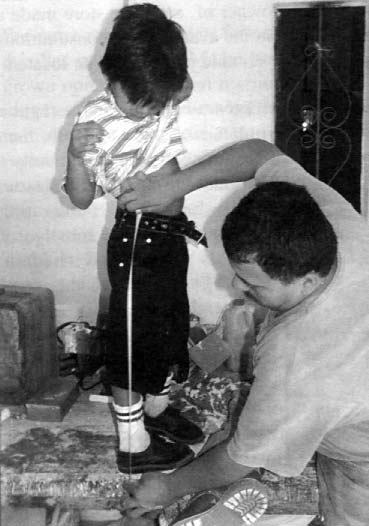

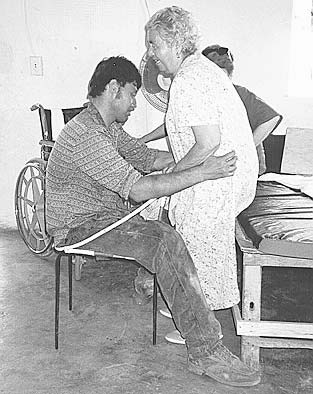

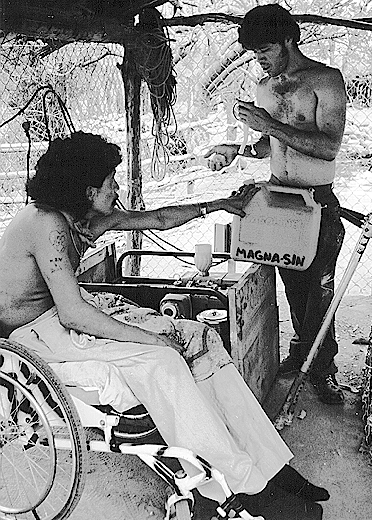

The PROJIMO team began to make regular visits to Coyotitán, first once a month, then once a week (Saturdays). The community’s response was enthusiastic. They formed a coordinating group made up mostly of parents of disabled children. This group spread the word to neighboring villages, and soon every Saturday disabled persons from a wide area of the coastal plains would come for consultations, advice, and lessons for home therapy. Inez, who has a leg paralyzed by polio and has worked with PROJIMO as a therapy helper for years, now goes to Coyotitán 3 days a week, to help people with therapy and advice (see page 10).

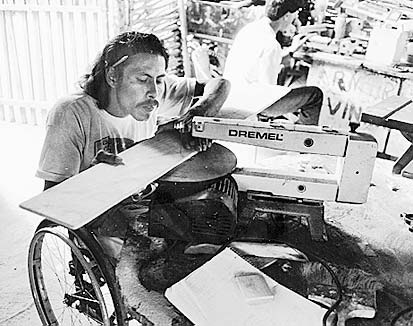

A make-Shift center. Last July, Cleto (an ex-village health worker who profited handsomely from drug trafficking) lent PROJIMO a large house he had built in Coyotitan, and then abandoned. In this building, Marcelo and Armando (two disabled PROJIMO workers with years of experience) set up a shop to make plastic leg braces and artificial limbs. Dolores Mesina, a PROJIMO graduate who is disabled by polio, is a social worker in charge of disability needs with the government program of Integral Family Development (DIF) in the city of Mazatlan. Dolores now takes van loads of disabled persons to the Coyotitan center for orthopedic appliances, limbs, wheelchairs, and other assistive equipment.

Meanwhile, the Coyotitan villagers have been active in obtaining land on which a permanent community based rehabilitation center can be built. They arranged to purchase a I acre plot of land at a reduced price. The cost is being covered in part by the Municipal Presidency, in part by community-run fundraising activities, and in part with money raised by the PROJIMO team from outside funding agencies. At present, the villagers and the Municipal President are trying to get a government housing assistance agency (PRONASOL) to build a series of nine modest houses for the families of the PROJIMO team. (Each family will also contribute toward the land their house is built on.)

The future is open. It is too early to say if the move of PROJIMO’s rehab activities to Coyotitan will be successful, but developments so far are promising. Most important, the PROJIMO team, which a year ago was very discouraged and thinking of closing down, has revitalized. The workers are assuming more responsibility and working more as a team than they have for years. Key to this new enthusiasm, I believe, is the fact that the initiative for the new program is now completely a local venture, spearheaded by the disabled workers involved. (I, David Werner, had been very reluctant to make the shift to Coyotitan, partly because after 33 years working with villagers in Ajoya, I have strong roots here, and do not want to abandon my friends at a time when their village is in deep trouble. Therefore, only with considerable emotional resistance did I accept the team’s majority decision to move to Coyotitan. The initiative has been conceived and carried out—with a new sense of pride and full ownership—by the local team itself.) Today, seeing the eager response and support by the community of Coyotitan, and the renewed commitment of the PROJIMO workers, I am convinced they made the right decision. Nevertheless, I am unwilling to totally abandon Ajoya in its time of need.

Transforming PROJIMO’s Ajoya Center to Meet People’s Need for Income

After much discussion with the PROJIMO team and the Ajoya towns people, it was decided that rather than moving the whole of PROJIMO to Coyotitan, the program would be divided into two bases. Most consultation and rehabilitation activities would relocate to Coyotitan, where they would be more easily accessible to more people. Meanwhile, the grounds and buildings of the old PROJIMO in Ajoya would gradually be converted to a work-skills training program and production center, which would strive to provide both skills and jobs, not only to disabled persons but also to unemployed village youth.

The rational for this focus on providing work-skills and jobs to local youth is a direct response to the current crisis of crime and violence. In the village of Ajoya, many young people steal and commit crimes because their families are hungry and they see no alternatives. We hope that by providing job training and work opportunities, the young people will be able to satisfy their basic needs in a socially responsible way.

This work program is now just beginning. Enthusiasm in the village is high. Both the local village Syndico (mayor/police chief) and the Municipal President are eager to see the work program succeed. Everyone involved knows there will be difficulties and challenges. They realize that if crime and violence in the village are to be reduced, the work program must be open to the young people who have been involved in stealing and other crimes. Precautions will be needed to prevent tools from disappearing, and to find ways to discourage socially hurtful behavior. One plan is for workers to function as a cooperative, and that the earnings of each person be a percentage of the produce sold.

Steps Already Taken to Launch the Ajoya PROJIMO Work Program

The village has formed a Coordination Team comprised of some of its more responsible and concerned citizens.

Roberto Fajardo, a disabled villager who has been a key leader in the village health program for over 20 years and is a co-founder of PROJIMO, will be the primary organizer of the work program. Roberto is a highly respected community leader and activist. He has a wide variety of practical and organizational skills.

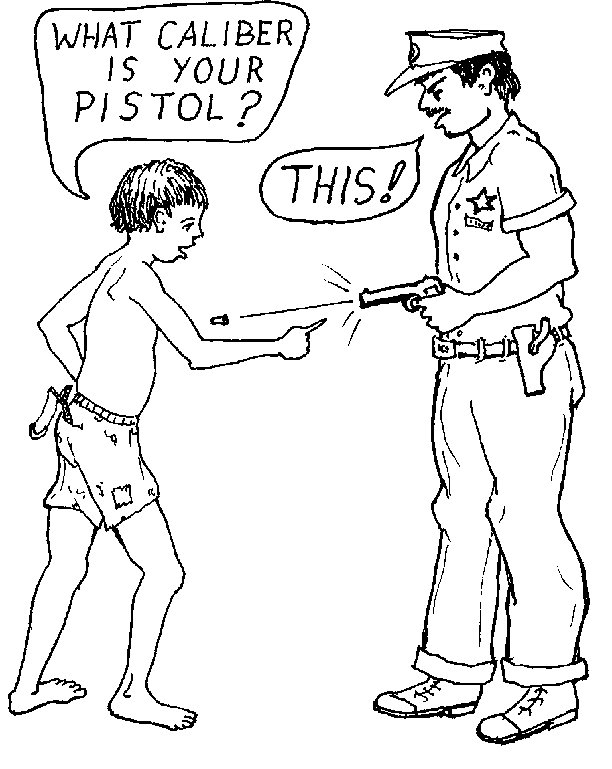

Chicken farming. This project was chosen because Miguel, a youth from Chihuahua who is hemiplegic, is staying at PROJIMO and wants something to do. Before his accident he had experience in chicken farming. So does Roberto. A set of chicken coups, long abandoned, has been cleaned up and reroofed with the help of village children. However, the coordinating team is worried that the chickens may be stolen (which is why the previous chicken farm was closed down). To minimize theft, the team is considering inviting a youth renowned as a chicken thief to work as a partner with Miguel on the chicken farm. (The boy, who recently became a father candidly admits he steals chickens to feed his family, because he has no work. But because he has a 45 pistol and hangs out with the village vigilantes, no one dares complain much. Helping him raise his own chickens could be a peaceful solution. Or it could be the door to new problems. Time will tell.)

Carpentry and coffins. Another work program now getting started is carpentry and woodworking. Although some people express discomfort with the project, it looks like the first line of production will be coffins. Death in a poor family is often a major disaster, not only emotionally but economically. It is now the popular expectation that the deceased be buried in a “modern” commercial casket. Even the poorest family goes into serious (and hunger causing) debt to obtain one. In addition to the price of the coffin (which is typically much higher than the materials and work that go into it) there is the cost of hiring a vehicle and driver to transport it from a distant town.

For years the village health program considered building (or a least stocking) relatively low-cost coffins, but never actually did so. But with the new work program, the coffin project is actually beginning. Roberto has talked with the Municipal President about the coffin building project. The President at once recognized the enormous unmet need and offered to cooperate. His offices and those of the Integrated Family Development program (DIF) are swamped with requests by destitute families to provide coffins for their dead. With the current increase of poverty and violence, the costs of death are especially high. The price of even the cheapest commercial coffin is exorbitant. The President not only offered to lend money to buy start-up materials, but also paid for an inexpensive cloth covered wooden coffin to use as a model.

Two disabled workers with good carpentry skills, who left PROJIMO years ago, have agreed to come back to head the woodworking project. One is Fernando Ramos. He had his own carpentry shop in Mazatlan, until one night a few months ago when all of his tools were stolen. By working and teaching in the Ajoya woodworking program, Fernando hopes to earn money to replace his tools and start up his own shop again.

Repair of school desks. The Coordinating Team recognizes how important it is to find ways to market the articles they produce. In this, the Municipal President is being quite helpful. He is trying to arrange to have the PROJIMO Work Program repair broken desks and chairs from schools throughout the municipality. This will provide an ongoing source of work and income for several young persons in Ajoya.

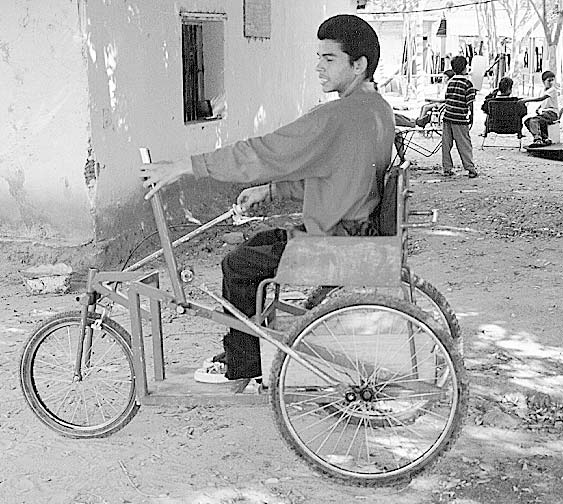

Welding services. PROJIMO already has a well equipped welding shop and experienced welders (wheelchair makers) who provide local repair services for broken plows, bicycles, kettles, etc. The workers have also made a variety of welded objects for sale or on special order, including metal bed frames, windows, doors, crosses (for graves), etc. The Municipal President has offered to place orders for windows, doors and other items for government office and school buildings throughout the municipality. This should provide a source of work and income for several persons. Marcelo and Jaime (disabled crafts persons at PROJIMO with long experience) have offered to help teach welding skills to local youth.

Training courses for work skills. Not long ago, members of the PROJIMO Work Program coordinating team met in San Ignacio with the Municipal President and the state-level directors of Centers for Capacity Building Skills (CECATI), an experimental new work-skills training program run by the Ministry of Education. This program provides training courses for a wide variety of formal and non-formal work skills, to groups of 25 or more unemployed youth. The community picks the course or courses it wants, in subjects that range from sewing and clothes-making, leather work, and shoe making, to carpentry, welding, bee-keeping, masonry, repair of electrical equipment or motors, computer skills, secretarial work, and various agricultural skills. What is exceptional in this program is that the students are are offered a minimal wage salary while they study. Work skills for disabled persons are also included.

The directors of this government program were excited about the Ajoya work-skills program, especially since it was initiated and run by the community itself. They have offered to cooperate fully. The Municipal President (for the first time in years) and the directors of the Ministry’s training program visited Ajoya to meet with the villagers. Plans are under way to start a series of 3-month work skill courses in Ajoya. Probably the first course will be on sewing skills and dress making, since there is a lot of interest in this among women and girls.

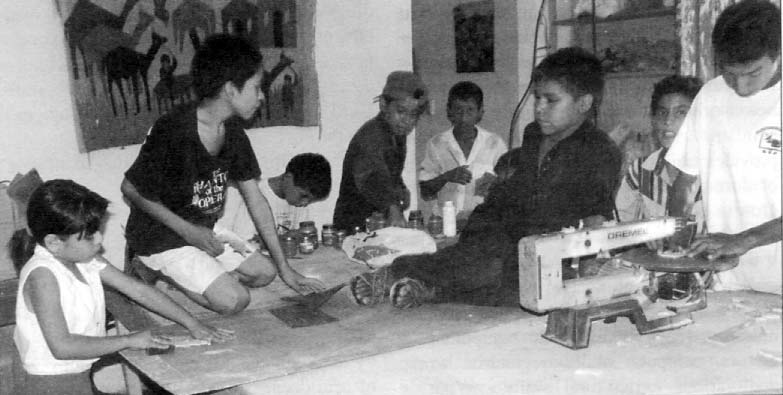

Toy Making. For years PROJIMO ran a children’s toy-making workshop where disabled and non-disabled children made educational toys and colorful wooden puzzles. Toy-making helped the children develop dexterity and learn useful skills. Until a year ago, two energetic teenage girls ran the shop and lovingly guided the young children. But unfortunately, due to so much violence in the village, the two girls have been sent to live with relatives in the city. Marielos, a paraplegic young woman, has taken charge of the toy-shop. She makes high-quality puzzles, doll-houses, and to furniture, all of which she sells locally. But Marielos is a perfectionist. She is frustrated by the spontaneous, exuberant, sloppy work of children. So the children soon felt unwelcome. They stopped coming..

Where Children’s Work is Child Play

One day a 17 year-old boy named Tino, who has chronic asthma and has hung around PROJIMO for years, arrived asking for a loan. He explained that his father presently had no work. The marijuana that Tino was growing on a distant hillside on weekends was not yet ready for harvesting. His family was hungry. Tino is a gentle boy who only recently began to carry a 45 caliber pistol (at a much older age than many boys). When he was younger he had enjoyed helping in the children’s toy-making workshop, and had become a skilled crafts-child. So the coordinating team of the Work Program offered Tino a job setting up and running a new Children’s Toy-Making Workshop.

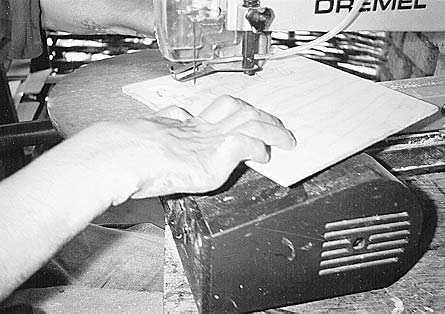

Tino is now doing a wonderful job. In the afternoons after school, he works patiently with a group of about a dozen children aged 5 to 13, teaching them how to draw figures, cut them out with a jigsaw, sand them, paint them, and then clean up afterwards (the most difficult skill of all to teach a group of rambunctious children).

Christmas tree ornaments. Tino and the children in the new toy shop are now busy making colorful wooden Christmas tree ornaments. The small figures are easier to make than wooden puzzles and for crafts children give quick, satisfying results. Ornaments include typical Christmas things such as Santa Clauses, angels, and shooting stars but also donkeys, cats, coral snakes, sea horses, monkeys, snails, and smiling children (both disabled and non disabled). Each figure is painted individually according to the particular child’s whims and ability.

A lot of the wood used to make these figures is from discarded fruit crates or lumber scraps which children help to collect. So the youngsters learn the importance of recycling and conservation of natural resources.

This Christmas-tree ornament project is an experiment. The figures can be used as decorations for Christmas trees, or as curious wall hangings, especially for children’s rooms. (So you don’t need to be Christian or have a Christmas tree to enjoy them!)

The children who make these objects have the choice of taking them home for decorations or for younger brothers and sisters to play with. But for each figure they take home, they are asked to make another one as part of a set to be sold (if possible).

PROJIMO and the children hope to find a market for these decorative, hand-painted figures. The above photo shows some of the figures made by the village children.

Some of the children helping to make these wooden figures are disabled. Money from sales of these wooden figures will go to the children who painted them. We hope some of our readers will order a set. IF YOU HAVE IDEAS FOR SALES, LET US KNOW

NOTE: This is not “child labor” in any coercive or negative sense. It is a fan, playful, cooperative, after-school skills learning activity in which children take part joyfully and voluntary. If successful, it will also be a way for them to earn a bit of pocket money, which many rarely have.

Tere’s white doves. One of the biggest small successes of the new Children’s Toy Making Workshop to date has been with Tere. Tere is an older disabled girl who is chronically unhappy. She has a congenital condition resembling multiple sclerosis, which affects her movement and speech. Because her older sister (now dead) had the same condition, when Tere was 5 years old her mother sent her to an orphanage. At age 16, Tere moved to PROJIMO. The team worked with Tere in a variety of ways, but despite repeated efforts could never get Tere interested in any kind of recreation or productive activity (other than occasionally washing her own clothes, which she did grudgingly, with difficulty). Until recently, Tere spent most of her time slumped in her wheelchair, waiting for her mother (who never came). She had few friends, and complained about almost everything and everyone. Sometimes she even resisted being bathed and changed. The team was at a loss with how to help her . . . or even reach her.

Recently, after a bit of heart-to-heart “peer counseling,” to everyone’s surprise Tere agreed to take part in the Christmas-tree ornament-making project. At first it was hard for her to paint the figures with her spastic arms. But Tino patiently guided her hands and helped her learn to support her arm on the table to stabilize her movements. She had trouble painting muti-colored figures, so Tino had her paint a dove all white. Then, holding her hand, he helped her paint a black eye and a yellow beak. The result was attractive. Tere was thrilled. Since then she has been taking part daily in the toy shop and seems happier than we have ever seen her before.

Small Loans to Start Work

Years ago, Project Piaxtla organized a farm workers’ cooperative maize (corn) bank. It loaned sacks of grain to poor farmers at planting time, to be paid back at harvest time. The maize bank was set up to break the back of the usurious loan system where poor farmers who borrowed from rich landholders had to pay back 3 bags of maize for each bag loaned. The bank was run as a cooperative where everyone benefitted when they all paid back their loans. So few people failed to pay. In the long run the loan program was so successful that people could pay off their debts and save for lean times-so the maize bank closed down.

Now, on a very modest scale, the PROJIMO work program is experimenting with a loan program to help poor people buy the tools or materials for small home-based production of crafts or produce, which they can sell.

While the work-loan program is open to lending small “start-up loans” to individuals, its main aim is to help small groups start mini-cooperatives. An example is the chicken farming project, in which disabled and non-disabled youths are beginning to work together and share their earnings.

What triggered the idea for a loan program was a request by Cecilia, a disabled member of PROJIMO. Cecilia is married to Inez (see page 10), who is a physical therapy helper at PROJIMO. Cecilia and Inez have 2 active young daughters. To help meet their expenses, Cecilia—who is skilled at knitting and embroidering—asked for a loan for materials to make decorated Christmas stockings, and other items, which she can sell for a profit.

In Conclusion . . .

PROJIMO is in a state of transition—a creative response to the growing wave of assaults and violence. The team of disabled workers is starting a new rehabilitation center in a safer, more accessible village (Coyotitan). The local community there is participating enthusiastically. Meanwhile, responding to an urgent request by families in the village of Ajoya where PROJIMO’s original base is located, this base is being converted into a skills training and income generating program. If this endeavor develops as planned, it will provide training and productive, income-generating work both for disabled persons and for local non-disabled, troubled youth. The goal is to provide socially positive options to young people who for lack of alternatives have turned to drugs, crime and violence. The future is still uncertain, but the new work program is off to a spirited start. For the first time in years, there is a new sense of hope in the village of Ajoya. Already there are signs of an ebb in the tide of local violence and crime.

Win or lose, people are vitalized by seizing the reins of their destiny.

Ways you can help PROJIMO’S new endeavors

DONATE TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT: Hand and electric tools and supplies for carpentry, furniture making, welding, leather-work, shoe making, sewing (including electric and treadle sewing machines), and wood-burning. Ask us for details.

DONATE COMPACT PC COMPUTERS: If PROJIMO can get a few used computers (in good condition) donated, it may start a computer skills training program in Ajoya.

VOLUNTEER: If you have carpentry, or toy-making, welding, leather work, or computer skills and would like to make a short visit to PROJIMO to teach your skills, please contact us. We also need volunteers willing to drive donated supplies to Mexico.

DONATE MONEY: Now that PROJIMO will have a center in 2 villages, it needs a lot of new equipment. Also funds are needed to help workers moving to Coyotitán obtain housing and construct the new center. Donations through HealthWrights are tax deductible.

Are You Interested in Reading More on Piaxtla, PROJIMO, or the Social and Economic Crises in Mexico?

If so, we can send you any of the back issues of Newsletters mentioned in the preceding article, for US $5 each, postage included.

Or we can send you a set of 6 relevant Newsletters for only $15, postage included.

Our new book, Nothing About Us Without Us, has detailed descriptions of many of the disability-related events and technologies described in this Newsletter. See the flyer.

Our other new book, Questioning the Solution: The Politics Of Primary Health Care and Child Survival, discusses the root causes of the global crises in health, economics, crime and violence. It also includes a detailed Chapter on Project Piaxtla and PROJIMO. See the flyer.

From our New Book NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US: Chapter 44, on ‘Ways to Work’

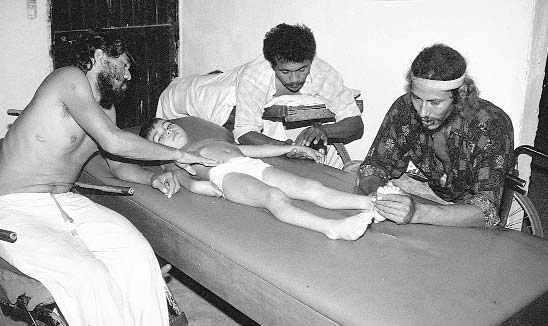

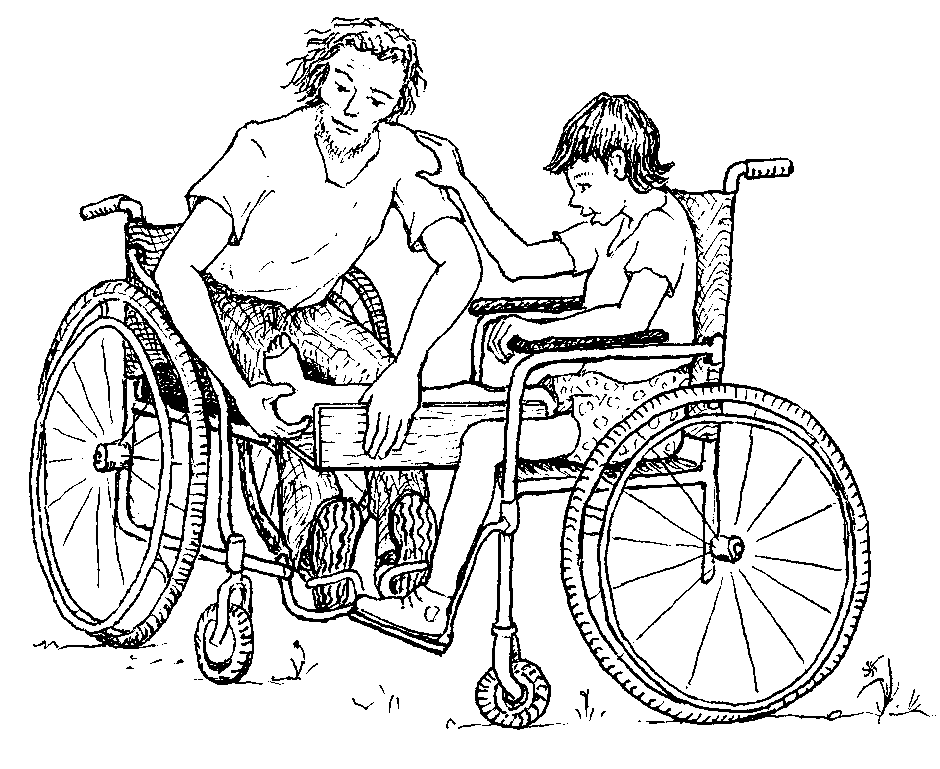

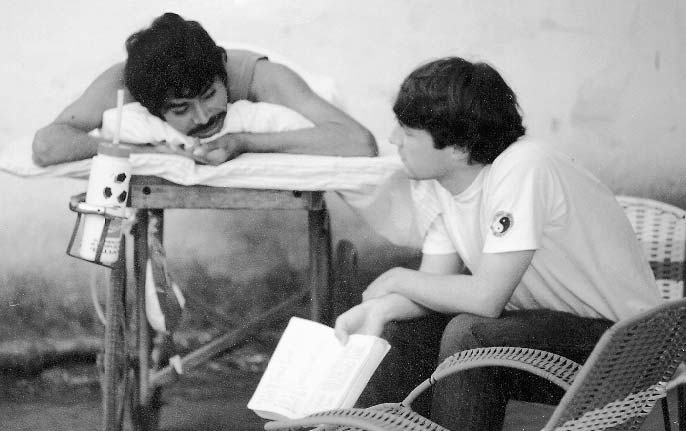

Disabled people helping one another provide a lot of the skills-learning at PROJIMO. Some young persons who first came for their own rehabilitation have stayed on at PROJIMO to learn the craft, organizational and rehabilitation skills that most interest them. Several have become very capable therapy-workers and craftspersons. One example is INEZ, who first came as an abandoned street child, with one leg paralyzed by polio. Inez has become a skilled therapy worker, having been taught by visiting physical therapists.

Inez became such a capable therapist and rehabilitation worker that, after a few years at PROJIMO, he set up his own successful physiotherapy practice in the city of Mazatlán. In time, however, he gave up the private practice and returned to PROJIMO. He preferred working as part of a community-based team to help those with limited resources. Inez married another PROJIMO worker, Cecilia, and has two energetic daughters.

Carpentry skills. The PROJIMO wood-working shop is where many disabled youth apprentice in making all kinds of equipment for disabled children, ranging from special seating and standing frames to educational toys. With the skills learned in this shop, some of the disabled young people have gone on to set up their own carpentry shops. Others have joined rehabilitation programs where they can put both their carpentry and rehabilitation skills to good use.

Even some of the young people who are quadriplegic (with paralysis of their arms and hands as well as legs) have become skillful carpenters and toy makers. The first obstacle for them to overcome is their feeling (and fear) of incapacity. The beauty of PROJIMO is that new-comers have excellent role models to follow. They dare to try new things and to test—and stretch—their limits.

Business Skills. Several disabled persons at PROJIMO who collectively run the program have also learned some organizational skills, and also bookkeeping.

Conchita studied accounting before she became paraplegic. Now she is a coordinator of the program and manages the financial records. She has taught other workers to help with accounting and program records. These skills can be useful for those who later set up their own small work-shops or cooperatives.

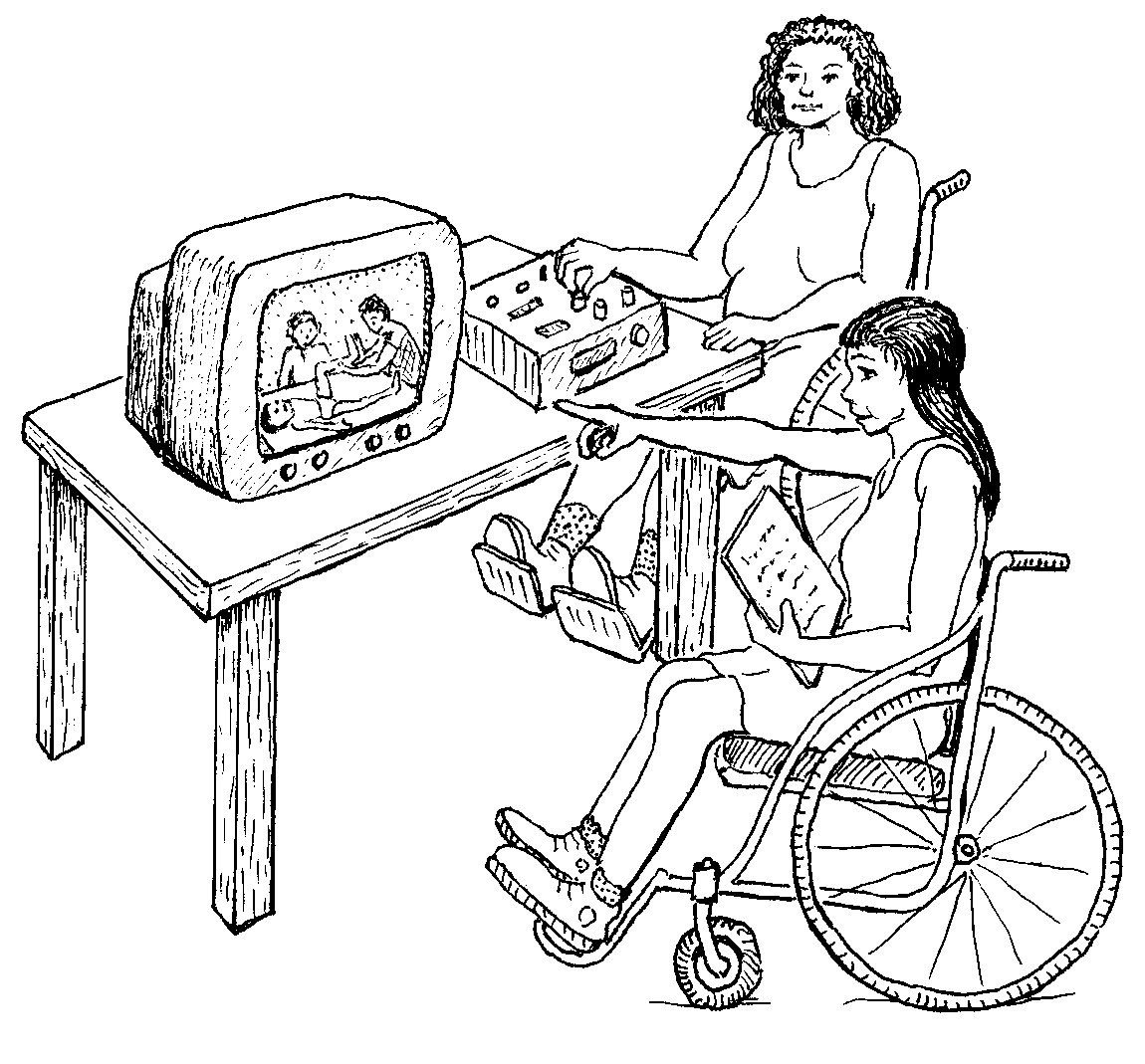

Video skills. Some work opportunities are unplanned. The PROJIMO team decided they should make educational videotapes of aspects of rehabilitation and therapy where movement is important, and where words and drawings are not sufficient. So they raised money to buy a video camera and recruited a skilled filmmaker to come teach them how to use the equipment, and put together and edit a film. Mari and Conchita, the two main coordinators of PROJIMO, mastered these skills.

Video cameras and film making was a new and exciting event for the local villagers. There are 3 or 4 video cassette players in town. Local people begged to have pictures taken of themselves and their families. Having acquired the needed skills, Conchita and Mari soon found themselves invited to take videos of events such as baptisms, weddings, and the coming-of-age parties of 15-year-old girls. Making and editing of videos has become one of the more successful income-generating activities of PROJIMO.

Maintaining PROJIMO’s Grounds and Buildings

The maintenance of PROJIMO provides skills training and practice at a range of tasks useful for maintaining a home or business.

The Spanish Language Training Program run by disabled villagers. For persons whose disabilities extensively limit the use of their bodies and hands, finding work opportunities can be quite a challenge. This is especially true for those who have little or no formal education—which is often the case.

One skill such persons do have in Mexico is speaking Spanish. So the PROJIMO team decided to start an intensive Spanish language training program. For the first classes they invited foreign students who, in exchange for being taught conversational Spanish, would help teach their teachers how to teach. PROJIMO especially welcomes language students who are disabled activists, rehabilitation workers, or progressive health workers. (If you are interested, send for a brochure. Fees are modest and help support the program.)

VICTOR, a young doctor, gave PROJIMO one of its biggest rehabilitation challenges. Soon after graduating from medical school, Victor broke his neck in a car accident. He spent months in a hospital, where he developed pressure sores and urinary infections. He had become suicidal. He was sure he could never work as a doctor.

At PROJIMO, Victor gave the village team a hard time. He did not believe that a group of uneducated villagers—disabled ones at that—could do anything for him. But, little by little, his sores healed and his health improved. He learned to use his hands to grip things by bending his wrists backwards. In time, he started to provide medical services to sick villagers. Victor became one of the exceptional doctors in Mexico who chooses to work in a poor and rural community. (In Mexico City there are over 5000 unemployed doctors who refuse to go to the poor rural areas where they are needed.)

News and Activities from the INTERNATIONAL PEOPLE’S HEALTH COUNCIL

IPHC Meeting in Nigeria took place on August 16, 1997

Dr. Abdulrahman Sambo, IPHC representative from Nigeria, reports that this meeting was very successful. The decision was made to form an IPHC Chapter in Nigeria, which will be legally registered as an NGO.

A report of this first IPHC meeting in Nigeria is now being prepared. It is exciting that Nigeria has set up its own branch of the IPHC and is moving forward into action. We hope other country representatives will follow suit.

With the recent crack-down by the Nigerian government on popular movements that defend the health of the environment and the people against powerful multinational interests, it is especially important that the IPHC help build grassroots bridges between activists in different sectors.

In Mexico IPHC and Center for Social Assistance plan meeting

Ricardo Loewe, IPHC coordinator from Latin America, has announced a “Seminar on the Quality of Medical Care” to be held in Tepoztlan, Mexico, February 22 to March 1, 1998. The objective will be to “share and analyze perspectives on the ethics and quality of medical care, especially to disadvantaged groups.” While most participants will be from Mexico, some will be from other countries.

IPHC Regional Meeting planned in Kerala

Dr. Ekbal, IPHC representative in India, is planning a regional meeting of the IPHC in the State of Kerala, India. The meeting will probably be held jointly by the IPHC and the People’s Science Movement, of which Dr. Ekbal is a leader.

A New Booklet from the Philippines: Understanding HIV and AIDS

This excellent down-to-earth booklet takes a very human and enabling approach to informing people about HIV and AIDS. It makes clear that it is not the virus alone that causes the spread of AIDS, but rather the virus together with factors such as poverty, prejudice, and gender inequality. To overcome AIDS we must work toward a fairer, more caring society.

Increasing Public Interest in Our New Book, QUESTIONING THE SOLUTION

Since it first appeared in print early this year, Questioning the Solution, The Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival has been gaining increasing attention. It has already been reviewed by leaders in primary health care and social analysis from various corners of the world: including Vietnam, Australia, South Africa USA, and England. Here are examples from 2 reviews:

In the Journal of Primary Prevention, Victor Nell of the Human Sciences Research Council of the University of South Africa Research Unit says:

“What the book is about is not oral re-hydration: it is about power and duplicity, and the poor weapons that ordinary people have against the might and wealth of the powerful.

“But hope never goes away …. I would like nothing better than to believe, against the weight of history and reason, that a lucid and timely book may yet sow the seeds of a revolution. This volume is a strong candidate: it elegantly states the problem, and sketches the diversity of ways it has been addressed in a variety of settings over the past several decades. Whether or not it wins the battle against power and greed, this book is a powerful addition to the primary prevention library and to the teaching curriculum—for which I would strongly recommend it—across a range of courses, such as comprehensive community based health care in medical schools, community psychology, developmental studies, international politics, sociology, and macroeconomics.

Claudio Schuftan, who works in Vietnam and has himself written many groundbreaking articles on the politics of health, says:

“I could not agree more with the authors in that a need exists to launch a concerted global effort to consolidate popular movements that think globally and act locally. This by creating opportunities for popular pressure to demand the social transformations needed to counter the regressive social trends we are seeing.

“At the heart of the conclusions of the book is a call for a Quality of Life Revolution in which children will not only survive, but will be healthy in the fullest sense of well-being.

“Even people politically unsympathetic to the book’s political line will find it worth reading. Students will find endless inspiration.”

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Allison Akana |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Myra Polinger |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| International Advisory Board |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Maya Escudero — USA/Philippines |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| Pam Zinkin — England |

| Maria Zuniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| Trude Bock — Editing and Production |

| David Werner — Writing and Illustrating |

| Efraín Zamora — Layout, Writing |

| Jason Weston — Layout and Online Edition |