This newsletter looks at a number of innovative efforts to make life better for children who have been living in difficult circumstances and who have especially challenging needs. It starts with a look at Nicaragua, where growing economic disparity has made it necessary for many families to choose between buying food and educating their children. But dire need gives rise to some encouraging and soul-warming initiatives. One is LOS CHAVALITOS, a farm school in the central highlands of Nicaragua. Another is the recent region-wide Encounter of children and youth engaged in CHILD-TO-CHILD activities. In the latter, kids share experiences and explore ways to comfort and help one another in hard times following the devastation of Hurricane Mitch. Next we look at a SPECIAL SEATING COURSE where folks from Community Based Rehabilitation programs throughout Mexico worked in partnership with disabled children and their families to design seats that increase the children’s comfort and abilities. Finally we announce the PEOPLE’S HEALTH ASSEMBLY —an effort to get at the roots of growing inequality worldwide.

‘Los Chavalitos’—A Unique Farm School in Rural Nicaragua: An Oasis of Learning in Balance with Nature

In a remote area in central Nicaragua, in February, 1999, David Werner and Martin Reyes had the opportunity to visit an extraordinary initiative called LOS CHAVALITOS (The Kids), also known as the Farm School. David Werner reports on this astounding, idealistic, yet very human initiative.

An oasis of learning for sustainable agriculture and humane development, Los Chavalitos is located in a cloud forest 100 miles from Managua where there are still patches of relatively unspoiled jungle, lots of animals and birds, wild orchids, 3 kinds of native monkeys, and several species of plants and animals that are unique to the area.

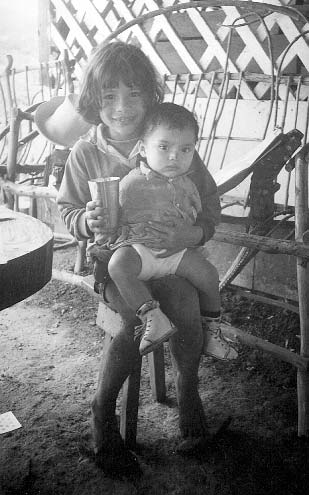

Los Chavalitos was begun and is facilitated by a remarkable man named Alejandro Obando, a down-to-earth visionary who has dared to follow his dream of providing a nurturing environment for neglected children where they can learn to live in harmony with one another and with nature. As a sort of extended family, in the last two years Alejandro has brought together a group of 15 homeless, abandoned, orphaned, and/or mistreated kids from nearby towns and from the streets of Managua, and relocated them to this idyllic homestead in the heart of the cloud forest. In a rustic school house that the children and volunteers helped to build, and on a farm the children help cultivate, this motley collective of disadvantaged kids and dedicated adults learn about living off the land and with one another in a gentle, sustainable, and wondrous sort of way.

The education of the children, while it loosely follows the government curriculum and is accredited, is in large part hands-on “learning by doing.” It emphasizes cooperation rather than competition, and the lasting rewards of conserving rather than exploiting the environment.

The children are schooled in cooperative self-reliance. They spend their mornings working on the farm, in a way where work becomes a kind of productive and satisfying play. They plant a wide variety of crops and tend seedlings of different trees, marveling at their miraculous growth day by day. They also take part in an extensive reforestation project, involving and serving as a role model for farmers on surrounding land-holdings. Their goal is to develop a form of environmentally friendly agriculture, which sustains and protects the natural ecosystems and biodiversity of the cloud forest. To this end they plant their food crops within, around, and among the natural flora and fauna. No insecticides or artificial fertilizers are used. Great effort is placed on preserving and, where needed, restoring the forest cover of watersheds, ravines, and gullies.

In the afternoons, schooling is a bit more conventional. The children attend classes in the small schoolhouse they helped build themselves. Recently the government has provided a schoolteacher, but because of the remoteness and miles of muddy trail to reach the homestead, the teacher sometimes plays hookey. Fortunately, however, at the Farm School there are frequently one or two idealistic volunteers (Mexican or North American) who teach the children cooperative life skills in an informal, learning-how-to-think, discovery-based context.

The children, 7 to 13 years old, are like flowerbuds cautiously beginning to open. They take pride in feasting on the corn, beans, fruit, milk, and eggs of the plants and animals that they themselves have tended. All in all, it is wonderful to see a corner of this tormented country where human beings live in such harmony with each other and with nature, and where children can look into the future with pride and hope.

How Conserving the Forests Helped Protect Los Chavalitos Against Hurricane Mitch

In the Camoapa District, as in much of rural Nicaragua, most of the forests have been cut down for cattle grazing. This rampant deforestation has led to denuding of the hills, and severe flooding of rivers together with mud slides in the rainy season. When driving through the district of Camoapa, in the far reaches of which Los Chavalitos is located, Alejandro pointed to the barren hillsides, and to the many small, dry stream beds.

“You see these dry sandy arroyos,” said Alejandro. “When I was a boy, we used to swim in them. They were always full of water, even in the drier months. The hills were covered with forests. The forests helped hold the water and feed it little by little to the streams, preventing flooding yet keeping them flowing. But since the hillside forests have been clear-cut and overgrazed, now when it rains, the streams flood their banks, and soon after the rain stops they are dry again. But you will see that at the Farm School, the valleys and ravines are still largely forested, and we are constantly planting more trees. So the arroyos don’t flood as much, and they always have water for the children to play and bathe in.”

The vast extent of deforestation in Central America is one of the reasons why Hurricane Mitch, in November 1998, caused such wide-spread, devastating damage. The storm took hundreds of lives and left hundreds of thousands of families homeless in Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador. It destroyed millions of acres of agricultural land. On the way from Managua to Camoapa we passed make-shift settlements of thousands of small shelters made of black plastic sheeting stretched over poles. It looked like the refugee camps after a major war. The rage of offended nature was overwhelming.

By marked contrast, the area where Los Chavalitos is located was largely spared the wrath of Hurricane Mitch. Despite the steep hillsides and deep ravines, there was practically no damage to the crops, the land, or the buildings in this region. This is in part because of the effort of the Farm School to preserve and restore the forests, and to farm the land in a sustainable and ecologically supportive way.

Sharing Ecologically Sound Farming and Reforestation with Neighbors

One exciting aspect of the Farm School is its positive influence on neighboring farmers in the cloud forest. In fact, Los Chavalitos is a school for the entire rural community. They welcome neighbors and visitors; they show them their innovative, ecology-sustaining farm methods, and the healthy harvests that result. They show them the thousands of seedlings they have planted in forest-sheltered nurseries: everything from citrus, mango, pineapple and many other kinds of tropical fruit, to bamboo and lots of local cloud forest trees and shrubs. They even grow Neem trees, a much lauded medicinal plant from India.

In this reforestation project, as well as in many of the small scale experiments with environment-friendly agriculture, Los Chavalitos has the eager assistance of professors and students from the Rural University of Camoapa, an “open university” which Alejandro helped initiate.

The thousands of seedlings of the many different trees and shrubs are freely shared with neighboring farmers, who—following some initial scepticism—are awakening to the advantages of reforestation and sustainable agriculture.

Little by little the landscape is changing, becoming greener and more forested. Streams flood less and flow longer. And people are discovering that by learning to live in harmony with one another and the environment, life can be more secure and more rewarding.

The children learn these truths through hands-on practice. And the neighboring adults are learning from the children.

Oh, Rats!

If it sounds poetic, it is! Yet every heaven has its moments of hell. In the wake of Hurricane Mitch, with all the spoilage and death, most of Nicaragua has been overrun by an epidemic of rats. They are everywhere and into everything. Their prevalence is such that the contamination by rat urine in homes and food stuffs has caused an epidemic of Leptospirosis, a debilitating and sometimes fatal viral infection. A nationwide education campaign to prevent and cope with Leptospirosis is now in full swing. Sadly, the corn fields at Los Chavalitos have also been overrun by rats. In some parts of the fields, on the towering plants a third of the ears of corn, once fat and healthy, have been gnawed upon and destroyed. The rats are so prevalent that the children frequently go in brigades into the fields with sticks and club the scurrying rats to death.

While this can be regarded as a form of “biological pest control,” it is far from gracious or fully effective (although for the kids it is a sporting challenge to their hunting instinct). So any reader who has an idea for a better, ecologically sound way to control the rats, we welcome your suggestions… Maybe it’s time for another Pied Piper!

Like any groundbreaking initiative for improvement and change, Los Chavalitos has its problems and even contradictions. But it is one corner of the Earth where a small group of people have a dream, and that dream is having a ripple effect, reaching, awakening and changing others.

Los Chavalitos is an adventure in loving and sustainable existance that humanity would do well to learn from. With more endeavors like this at the micro level, perhaps we will someday move to the sort of macro-change that is needed to prevent the kind of mega-disaster that will make Hurricane Mitch seem like the skip of a heartbeat.

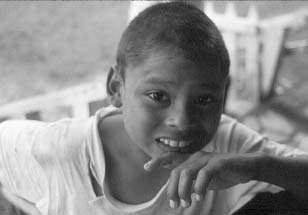

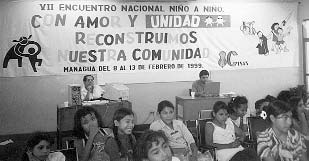

Child-To-Child Regional Workshop in Nicaragua: Helping One Another in Times of Stress

In Februrary, 1999, CISAS, the Center for Information and Training in Community Health, in Nicaragua, held a national workshop for sharing of ideas in Child-to-Child activities. Invited were children from 8-13 years old, and youths from 14-18 years old, who have been involved in Child-to-Child activities in many different areas of Nicaragua. There were also groups from El Salvador and Honduras. Helping to facilitate and evaluate the 6 day workshop were Martin Reyes and David Werner. Martin, who for many years was a leader in Project Piaxtla and PROJIMO in Mexico, for the past 6 years has been woking with CISAS to help introduce the practice of Child-to-Child thoughout Central America and beyond.

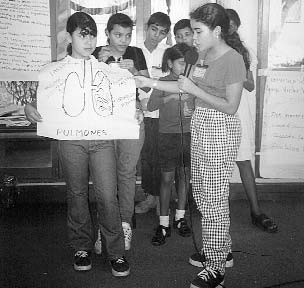

Child-to-Child is a learning-by-doing educational approach through which school-aged children learn to observe, analyze, and take action to help resolve health-related needs in their homes and communities. Although the concept began with the idea of children learning to help safeguard the health of their younger brothers and sisters, it has grown to include such activities as community gardening, reforestation and helping disabled children integrate into public schools.

At the workshop, groups of children from different areas gave presentations on outstanding activities they had realized in the last year. One of the most impressive activities accomplished by the children from El Viejo, dealt with the huge problem of accumulating garbage, which has added to the poliferation of rats and, since the hurricane, a nationwide epidemic of Leptospyrosis. The children started a profitable business of turning biodegradable household garbage into fertilizer. First they separate out the plastics and similar non-biodegradable garbage, which they burn. Then they mulch the organic garbage, alternating layers of garbage with layers of dirt, and water it regularly so that it decomposes quickly into a rich fertilizer, which they can sell to farmers and use in their community gardens.

One of the goals of Child-to-Child is to encourage children to think for themselves, analyze their common needs and to discover their underlying causes, and then to seek solutions cooperatively. This empowering approach called “discovery-based learning” has been strongly advocated in Latin America by Martin Reyes, who became a facilitator of Child-to-Child when he himself was an adolescent and junior health worker in the village of Ajoya, Mexico.

Following Hurricane Mitch in the fall of 1998, which caused a region-wide disaster, for a while it was questioned whether the Child-to-Child Workshop planned for February, 1999, should be canceled. But CISAS decided, and all the children concerned agreed, that the current “hard times” made the Child-to-Child encounter even more important.

It was decided that a key focus of the Encounter should be to explore ways that children and adolescents could be supportive of one another, and could offer a helping hand to those youngsters who had lost their home and even family members to the hurricane. So through stories and role-plays and sharing of experience, the young folks learned about ways they could be helpful and kind to the child who has suffered serious trauma and loss.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the Encounter was the vitality, spirit of joy, and resiliance of the children present. Many had lost their homes, their farmland and even family members or friends in the hurricane. They were able to discuss the enormity of their problems seriously, sometimes with tears of emotion. And yet they still knew how to put their problems aside, enjoy one another, enjoy themselves, and enjoy life. For me, in spite of inevitable shortcomings, the Child-to-Child Encounter was something of a renaissance: a celebration of the uncrushability of youth when given even half a chance.

We all learned a lot from one another, and came away from the experience refreshed and renewed by the children’s unbounding openness, honesty, and intelligence.

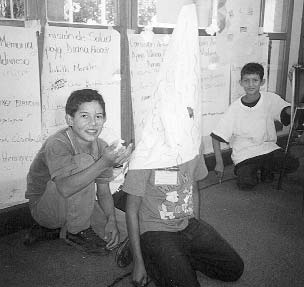

Images from the Workshop

Seats That Enable: Special Seating Seminar-Workshop in Culiacan, Mexico

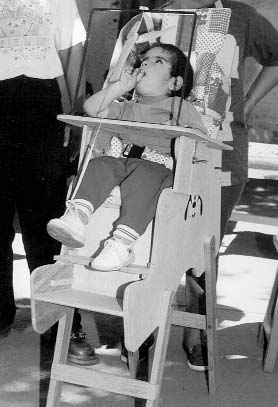

Especially for children with cerebral palsy, having a specially designed seat that helps them sit in a comfortable and functional position, can make a big difference in the child’s development and happiness. Yet most of these children never get such a carefully conceived and enabling seat. To design and build a seat to the needs of the child with a lot of spasticity or deformity is both a science and art. It is a skill that can be learned by working closely and sensitively with the child and her family.

On March 1-5, 1999, Jean Anne Zollars, a physiotherapist and seating expert from New Mexico, facilitated a mini-course in “Special Seating” at Más Validos, a Community Based Rehabilitation program run largely by the parents of disabled children in Culiacan, the capital of Sinaloa state, Mexico. The course was followed by a 2 day workshop held at PROJIMO, in the village of Ajoya about 100 miles away. David Werner was the co-facilitator of the course and workshop.

This Special Seating Course in Culiacan was a marvelous learning experience for all involved: program participants, parents and the disabled children themselves. Despite the large number of persons involved (107 counting those in the post-course workshop), the level of participation was remarkable. Many of the participants already had some experience making seating and other rehab equipment, and plunged in with enthusiasm and creativity. The close involvement with parents and the children themselves made the sharing and learning experience richer for everyone.

The first afternoon of the course began with visits to the homes of several disabled kids whom the Mas Validos team had selected as needing special seats. This was important, because the participants could begin to know the families and to understand the home and community environment in which the children lived. Decisions needed to be made for questions such as whether to add wheels to the seats or to fit seats into wheelchairs.

In some cases dirt floors and rough paths made addition of wheels impractical. Some parents needed to transport their children to school or therapy daily in compact cars or crowded buses. So size and collapsability of the seating was a concern for some families.

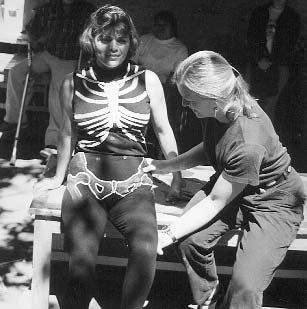

The second day was spent learning to evaluate the needs of disabled children. To help learners understand basic anatomy, tilt of the hips, the tightness of certain muscles, and the range-of-motion of major joints, Jean Anne used some excellent home-made teaching aids, including a flexible wooden skeleton designed at PROJIMO. Her best teaching aid was a black, skin-tight leotard (ballet suit) with a human skeleton painted on it.

Once participants learned the basic principles, Jean Anne demonstrated how to assess a disabled child, with the help of the mother and volunteers. Then participants divided into 7 groups. Each group assessed a disabled child with the help of the mother and/or father. The assessment was comprehensive, covering not only physical aspects but also the child’s abilities, potentials, and the wishes and concerns of the family.

The physical examination included supporting the child’ s body and hips with the hands (often of 2 or 3 assistants) to find out which position helped the child sit upright comfortably, with reduced spasticity and more control of the body, head and hands.

The third day in the morning, the 7 groups of participants planned the seat they thought would best serve the child and family, according to their assessment. They drew their designs on butcher paper. After lunch each group presented its design in a plenary session. Praise, criticism, and suggestions were solicited from the larger group.

The afternoon of the third day and most of the fourth day were spent by the groups in building the seat each group had designed.

Most of these children had spastic and or flaccid (floppy) cerebral palsy, with moderate to difficult problems sitting. When placed in a sitting position, some would arch up and slide off their seat. Others had such low muscle tone that their heads and bodies would droop forward, even with the chair tilted back. Through experimenting with these children in different positions, providing hand support in different locations on the thighs, trunk, and perhaps shoulders, the groups figured out what sort of seating might benefit each child. Then they set about constructing them. They used mostly plywood and fairly firm sponge rubber. They laminated cardboard (paper-based technology) for wedging and supports. Most of the seats were made with possibilities for easy adjustment, in terms of angle of the seat and back.

The fifth day was spent completing the seats, testing them with the children, and making needed alterations. Then, in a plenary session, each group (made up of participants, the mother, and the child) presented the child in his or her special seat.

Amazingly, almost all the seats made in the course worked well. Most of the children showed marked improvement in sitting. Several could hold up their heads in a better position and use their hands more effectively. Because parents were closely involved in the whole process of assessment, design, fitting and modifying their child’s special seat, they expressed confidence in experimenting with the seats, and according to their child’s response, in modifying them to meet their child’s changing needs over time.

A Seat to Enlarge the World of Jose

|

|

|

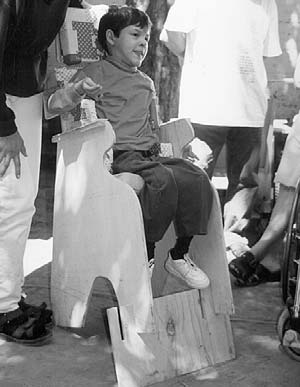

Juan de Dios—Riding Straight and Proud!

1. While most children at the Special Seating course, had cerebral palsy, 3 had spina bifida. Of these, the biggest challenge for seating was 5-year-old Juan de Dios. He has a severe deformity of the spine, with a big lump in the [middle of his back.]

2. When we at PROJIMO had seen Juan de Dios 6 weeks earlier, he had a huge pressure sore on the lump on his back, about 10 cm. high and 7 cm. wide. Present for 8 months, the sore had resulted from a plastic body-jacket prescribed to straighten his back.

At that time, we suggested his mother treat the sore with a paste of honey and sugar. We were pleased to see that at the course 6-weeks later, the sore was already almost completely healed. We congratulated both the boy and his mother.

3. Before the course began, Gabriel Zepeda, a paraplegic wheelchair builder with the PROJIMO Work Program, had designed and built a lovely small custom-made wheelchair for Juan de Dios. The backrest he padded with thick foam rubber, with a big hole cut out of it to avoid pressure on his angular back deformity.

In the first trial of the wheelchair, Juan de Dios was frightened of all the people and noisy tools. He began to cry. So Gabriel’s group took him into a quiet hall. Now the boy experimented eagerly with his new wheelchair. He quickly learned to propel and steer it himself. His tears changed into a broad smile of adventure and delight.

4. A design problem. Although the doughnut-like back-rest protected his back lump from future sores, when he propelled his wheelchair, Juan de Dios’ body bent forward a lot: his backbone bent like a hinge.

5. To help hold his back in a straighter position, the group made an experimental harness out of butcher paper reinforced by duct tape.

6. After repeated trials to work out difficulties and modify design details, Catalina and Gabriel sewed together an attractive harness (with shoulder straps) out of soft, padded cloth.

7. With his new harness, Juan de Dios is able to move about in a more upright position, with his backbone held straighter. This will help reduce the spinal deformity, let him breath more deeply, and allow more room for his internal organs—which may mean a longer, healthier, more active life.

|

|

|

Sitting upright in his personalized wheelchair, Juan de Dios’ voice now seems stronger and richer. Taking part in this friendly problem solving venture with disabled peers, his self-confidence blossomed.

Innovations at the Special Seating Workshop: Hanging Toys on Overhead Bars for Stimulation and Increased Control

Adjustable toy-bar. DIANA had meningitis as a baby, which left her brain damaged and visually impaired. To help stimulate her different senses and to use her hands, her group attached a “toy bar” to the table on her special seat. Toys that make different sounds and have different textures can be hung from the bar. Slots on the wooden uprights allow the bar to be adjusted up or down, forward or back, to look for the most functional position.

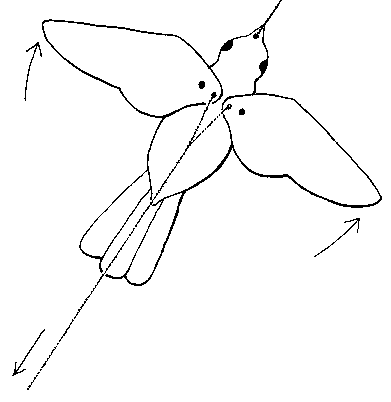

Flying bird. Participants designed this special seat for ALBERTO, a 3-year-old boy with cerebral palsy. For the metal toy-bar, Juan from Piña Palmera in Oaxaca (rear left) made a bright yellow wooden bird with wings that flap when a hanging string is pulled.

Alberto did not have enough hand control to pull the string on the bird. Half-joking, someone suggested attaching the loop of the string to the child’s foot. When this was done, every movement of his foot made the bird flap its wings. Alberto very quickly learned to swing his foot back and forth to make the bird fly. He loved the game and in the process learned more purposeful control of body movements.

Encouraging Disabled Children in the Creative Process

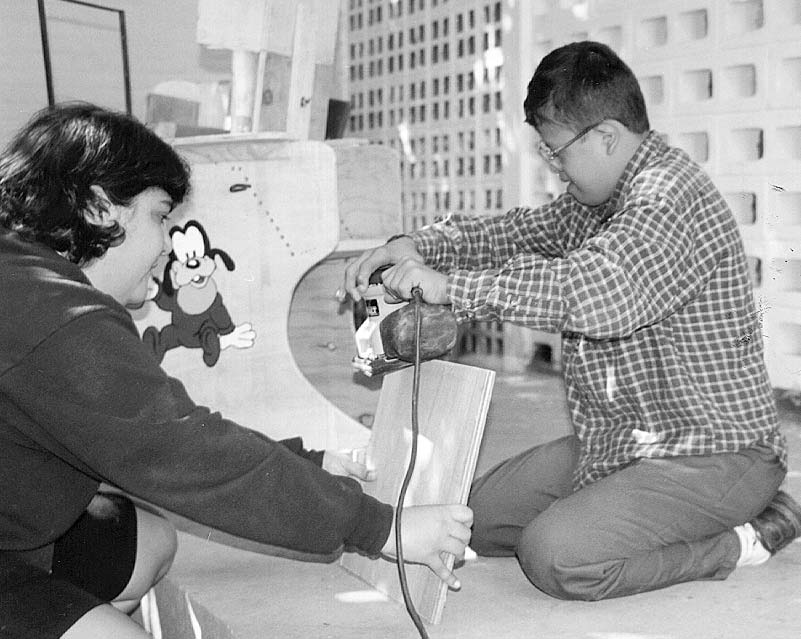

Alex is a friendly, alert, 14-year-old boy with Down’s Syndrome who appeared at the Special Seating Workshop. He has a curious mind and wanted to take part.

During the course, Bob Beyers–husband of Charlotte Beyers who runs Peregrin Productions and is making a video documentary of PROJIMO–loaned his camera to Alex to take photos. Alex was delighted. Other participants gave him different jobs. Here he proudly uses an electric sander to

smooth the table for a special seat.

Young disabled people have a right to learn skills and take certain risks, like non-disabled people.

Introducing The Enabling Education Network (EENET): ‘Promoting the Inclusion of Marginalized Groups in Education World Wide’

The Enabling Education Network (EENET) has been set up to establish an information-sharing network aimed at supporting and promoting the inclusion of marginalized groups in education world wide. Although membership is open to individuals and organisations in all parts of the world, EENET gives priority to the needs of countries in the South.

EENET:

-

Believes in the equal rights and dignity of all children;

-

Prioritizes the needs of countries which have limited access to basic information and resources;

-

Recognizes that education is much broader than schooling;

-

Acknowledges diversity across cultures and believes that education should respond to this diversity;

-

Seeks to develop partnerships in all parts of the world.

Begun in April 1997, EENET aims to fill a networking vacuum in the relatively new field of Inclusive Education (IE). While Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) workers and Disabled People’s Organisations sometimes link into regional and international networks, there was little opportunity for teachers and policy makers involved in IE to share their experiences. Because UNESCO’s Special Needs in the Classroom project lacks a networking service, it gives EENET its full support. Although Inclusion International has begun to network on Inclusive Education, it focuses on children with learning difficulties and works mostly with UN agencies. The need was seen for a more independent body that would look at inclusion in its broadest sense and could supply much needed relevant information to the field. And so EENET was born.

Most EENET’s members are concerned for disabled children. However, EENET has deliberately defined its objectives very broadly, to include all issues of difference and discrimination, such as race, gender and poverty.

Sadly, awareness training concerning any one group of marginalized persons does not guarantee awareness in others. So, for example, a person may be race and gender aware, but be completely disability-unaware (Stubbs 1995). EENET will encourage a more holistic view of disability in order to promote a fuller understanding of exclusion in its widest sense.

Inclusion, as distinct from integration, is a process by which the school and the system has to change to include disabled children and other marginalized groups. In integrated education, disabled children are sent to mainstream schools and the individual child is adjusted to fit into the school. Basically, the school stays the same. Hence the successes of integration have been too few, and a large proportion of children remain marginalized, or accepted on a conditional basis. We therefore have to rethink the task and ask ourselves: How do we prepare schools so that they deliberately reach out to all children? (EENET ‘97)

The opportunity of inclusion is to challenge the status quo of traditional forms of schooling and to bring about meaningful and lasting changes to the whole school which will benefit all children. In this way inclusive education dovetails with the school improvement and effectiveness movement to provide a better learning environment for all.

International Trends

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on and discussion about inclusive education as a strategy for responding to diversity. This strategy is gaining impetus globally. Sometimes this is from a rights perspective: “Disabled children and other marginalized groups have a right to be educated alongside their peers”. And sometimes this comes from an economic perspective: “We cannot afford or sustain segregated ‘special’ education, and so inclusion is the only option”.

The United Nations’ world conferences on “Education for All: Meeting Basic Learning Needs” held in Thailand in 1990 and on “Special Needs Education: Access and Quality,” held in Spain in 1994 emphasized that many children are excluded or are not benefiting from current systems, such as disabled children, street children and ethnic minorities. It is therefore important to look at the systems, structures and methods within schools to bring about a schooling system which can benefit and include all children within a particular community. The Salamanca ‘Framework for Action’ is being used to support policy development in several countries.

In the industrialised North the dominant model has been one of segregation, or institutionalised provision for separate categories of children. Attempts to adopt newer, more inclusive policies are hampered by a legacy of exclusion which can tie up resources and provide huge bureaucratic and attitudinal obstacles. By contrast, there is less legacy of segregation in Africa and Asia, and inclusive education is often more fully integrative and community-based than in the North.

However, seminars and publications tend to be biased towards the concerns of Northern countries because most funding resources and “experts” come from the North. There is a tremendous need in countries of the South to share experiences of the inclusion process.

The aim of EENET is to broaden the concept of inclusive education beyond the classroom to include community-based strategies and promote dissemination of useful information in accessible formats throughout countries with limited access to basic information and material resources. It promotes the positive identity of marginalised persons by encouraging and supporting self-help groups, and the involvement of positive role models. Individual differences are recognised and celebrated as part of the inclusion process.

Who is involved in EENET?

Members consist of parents, policy makers, teachers, academics and community workers. Partners include: Non-Government Organisations (NGOs), UNESCO’s Special Education Programme, and European research institutions. Funding agencies include: Norwegian International Disability Alliance (NIDA), Radda Barnen, and Associazione Italiana di Amici Raoul Follereau (AIFO).

How to contact EENET:

EENET, Centre for Educational Needs

University of Manchester, Oxford Road

Manchester M13 9PL

Tel: +44 (0)161 275 3510

Fax: +44 (0)161 275 3548

Email: eenet@man.ac.uk

For more complete information on EENET see the web-site: www.eenet.org.uk

A newsletter, “Enabling Education,” is also available, for sharing of information.

News and Activities from the International People’s Health Council (IPHC)

Plans for the People’s Health Assembly in the Year 2000

Health for All? In 1978 the world’s nations subscribed to the challenge of achieving Health for All by the year 2000. Primary Health Care (PHC) was to be the approach to meet this goal. However, as 2000 approaches, the goal remains distant. Levels of health in many countries have deteriorated.

This deterioration of well-being of a vast portion of humanity is a growing worry for many organizations, concerned groups, and spokespersons for the poor. During the last year a number of non-government organizations in health-related fields have begun working together to formulate healthier, more equitable, more sustainable approaches to health and development. Out of this shared concern has grown the call for a People’s Health Assembly (PHA).

First Planning Meeting. In November, 1998, a planning group for the PHA met in Malaysia. Organizations represented in the PHA

Coordinating Group include Consumers International, IPHC, Third World Network, All India Drug Action Network, Asian Community Health Action Network, Gonashasthaya Kendra, University of the Western Cape, La Trobe University, CISAS from Nicaragua, and the Dag Hammarskjold Foundaton, which is committed to help fund the Assembly. Detailed plans were discussed and drafted. Below is a brief summary of the report of this First Planning Meeting.

For more info on the PHA contact:

PHC Secretariate, Consumer’s International

250-A Jalan Air Itam

10460 Penang, Malaysia

Tel: 604-229-1396

Fax: 604-228-6560

E-mail: pha2000@tm.net.my

Summary of Plans for the People’s Health Assembly (PHA)

Date: December 5 - 9, 2000

Place: Bangladesh

Participants: 500 from 100 nations, mainly from NGOs, civil health oganizations and networks.

Goal: The goal of the People’s Health Assembly is to re-establish Health for All and equitable development as the top priorities of local, national and international policy-making, with Primary Health Care as the strategy to achieve these. The Assembly aims to draw on and support people’s movements in their struggle to build long-term solutions to health problems, in cooperaton with governments and international institutions.

Objectives of the PHA:

To hear the unheard. The Assembly will present people’s concerns and initiatives for better health, including traditional and indigenous knowledge.

To reinforce the principle of health as a broad multi-sectoral issue.

To formulate a People’s Health Charter.

To develop cooperation between concerned actors and groups in the health field.

To improve the communication between concerned groups, institutions and actors.

Sequence of events:

-

1999: Preparation of a pre-assembly “State of World Health” paper.

-

1999-2000: Country and regional preparatory meetings, with local reports.

-

Dec. 5-9, 2000: People’s Health Assembly Pre- and Post-conference training sessions and events.

If you are interested in learning more about the People’s Health Assembly, in helping to plan, or participating in local or regional pre-Assembly events, contact the above address. Inquire about the Coordinator in your region. Ask for a PHA form to become involved and receive info and updates.

News and Updates On HealthWrights and PROJIMO

Peace Returns to the Village of Ajoya: PROJIMO Work Program Takes Partial Credit

Nearly a year has now gone by without a major incidence of violence in Ajoya, the village where PROJIMO is based. There have been no recent killings, kidnappings, or assaults on buses, and the incidence of robberies has dropped considerably.

No doubt there are many explanations for this welcome return to peace. One reason may be PROJIMO’s new Work Program, which is providing skills training and income-earning opportunities for disabled and jobless youth. Apart from the persons employed on a regular basis, others earn money by bringing timbers salvaged from the river bed, which are used for making furniture and coffins. So more people have income from social-[work.]

PROJIMO Rehabilitation Program Builds a New Center in Coyotitan

For over 2 years the PROJIMO Rehabilitation team has been making preparations to move to Coyotitan, a village far less remote and more accessible to people living on the coastal plains. But the move has gone slowly due to limited funding.

At last, however, the team has completed construction of new workshops for building wheelchairs, and for making limbs and braces. The town government has provided free installation of electricity and water mains. Although the team members still do not have their own houses, they plan to rent provisional living quarters and move to Coyotitan after their children finish school this summer. (Already they go to Coyotitan on weekends for consultations and other services.)

HealthWrights Forms Links with International Groups Seeking Health Through Greater Equity

As globalization of the market economy widens the gap between rich and poor, the health of the planet and its people is compromised. HealthWrights is joining forces with several international groups working toward a model of sustainable development that puts the well-being of all before the economic growth of the already wealthy. These groups include:

-

International People’s Health Council

-

International Forum on Globalization

-

People’s Health Assembly (see page 10)

-

Third World Network

-

WHO’s world wide web “Supercourse” on “Health, Environment, and Sustainable Development”

HELP NEEDED! These networking activities in quest for fairer, more sustainable social structures require lots of work. Fortunately we now have a couple of new volunteers. But we opperate on a shoestring budget. We need more help, both finacial and vounteer.

Toy-Making Interchange at PROJIMO

In March, 1999, PROJIMO was visited by Nachiko Takagi, a young speech therapist from Japan who also specializes in educational toys. At the same time we were visited by Jim Clouse and Chico from the toy-making shop of Piña Palmera, a community rehab. program in Oaxaca. Toy makers from PROJIMO, Oaxaca, and Japan shared designs, work methods, and marketing practices.

It was a stimulating occasion, with lots of involvement of disabled persons and of local children, scores of whom fell in love with Nachiko. PROJIMO is determined to make its toy-making cooperative, which provides skills training and work for disabled youth and village kids, economically self-reliant.

How You Can Help

HealthWrights (in USA) Needs

Volunteers to help with:

-

administrative assistance

-

secretarial work and bookkeeping

-

preparation of books, newsletters

-

computer skills, troubleshooting

-

website and library maintenance

-

translations into Spanish

-

book invoicing, distribution

-

marketing of books, toys, crafts, greeting cards, bird prints, etc.

-

fund-raising, grant writing

-

networking and research

Donations (tax deductible) of funds and needed equipment.

PROJIMO (in Mexico) Needs

-

Short term volunteers in different fields of disability-related work, furniture. and toy making, wheelchair building,

-

Volunteers to drive supplies to Mexico.

-

Students to enroll in individualized intensive Spanish course taught by disabled youth. Low cost (see flyer).

-

Help promote the Spanish course.

-

Help marketing toys, crafts, and cards.

-

Tools and supplies for carpentry, welding, brace and limb-making.

-

Donations (tax deductable) to improve the Work Program, and to finish the new village rehab center in Coyotitan.

HealthWrights and PROJIMO, through our enabling programs, workshops, books, and networking, have influenced community-based rehabilitation and healthcare worldwide. Please help us sustain our groundbreaking work. To make a donation, you can use the enclosed yellow form. If you are able to volunteer, or if you have tools, equipment or supplies to contribute, contact us by mail, phone, fax or E-mail for details and to discuss possiblitites . . . Many thanks!

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Emily Goldfarb |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Donald Laub — Interplast |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| Pam Zinkin — England |

| Maria Zuniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| Margaret Paulson — Proofreading and Editing |

| David Werner — Writing, Drawings, Some Photos |

| Susie Miles — Writing about EENET |

| Efraín Zamora — Layout and Scanning |

| Trude Bock — Content Editing and Proofreading |

| Marianne Schlumberger — Proofreading |

| Martin Reyes — Some Photos on Pages 2-4 |

| Bob Beyers — Most of the Photos on Pages 5-8 |

Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.

—Albert Einstein