Prospects for a ‘Livable Future’—Dream and Reality

In August, 2001, the Mulago Foundation held a meeting of leaders from different community-based health and development programs that it assists in different parts of the world. The meeting took place at the bucolic headquarters of Future Generations near Franklin, West Virginia. The purpose of the interchange was to help Mulago and the programs reexamine their overall vision and consider strategies for immediate and farreaching change, in view of the problematics of the age we live it.

In our discussions it became clear that many of these programs are doing outstanding work at the local level. Most are committed to helping marginalized people in difficult circumstances find ways to cope with their pressing needs, in ways that also enable communities to conserve the natural environment. Some of the programs have been “scaling up” their successful approaches or finding ways to have a more far-reaching impact. All share a commitment to equitable and sustainable development.

I began to feel as if we were fervently building an ecovillage a foot above sea level, knowing that the polar icecaps will melt and our dream village will be washed away.

In presenting their vision of a livable future, nearly everyone at the meeting expressed concern about what they considered to be the socially and environmentally harmful aspects of “globalization.” They bemoaned the huge and often unscrupulous power of transnational corporations, and the way the current, top heavy model of economic development is so short-sightedly pursuing economic growth (for the rich) at enormous human and environmental costs. They have witnessed how the widening gap between rich and poor, and the cutbacks of social assistance to the poor, are leading to a pandemic of social unrest, crime, violence, hunger, resurgence of the diseases of poverty, population growth, and overuse of natural resources. They are aware that sweeping deregulation and the global reach of giant industries is accelerating unprecedented ecological degradation. Many of the program leaders present have witnessed how different aspects of these global forces, ranging from trade agreements to adjustment policies, have caused increased hardships or setbacks to both local people and to ecological stability in the corners of the earth where they work.

Despite these concerns, as the participants at the meeting described their “strategies for change” in working toward a “livable future,” most conceded that they were doing relatively little to confront the overwhelming threats posed by the unbridled global economic forces. For various reasons, they had preferred to keep their focus on the development of coping strategies at the local level. Based on their wealth of experience in community mobilization for change, they talked about the need for activities that give quick, visible results. The dangers to a sustainable future that are intrinsic to a development paradigm of unlimited growth seemed too huge to get a grip on, or even to face head-on.

I began to feel as if we visionaries of a “livable future” were fervently building an ecovillage on a bucolic island a foot above sea level, knowing that in a few years the polar icecaps will melt and our dream village will be washed away.

A key participant in the Mulago meeting at Future Generations was Dr. Carl Taylor, a pioneer of Primary Health Care and an architect of the Alma Ata Declaration. Among scores of groundbreaking activities worldwide, Carl worked for several years as a UNICEF advisor in China. Now 85 years old, he has a formidably ageless mind, wisdom, and wealth of experience that lead many of us to seek his counsel. After the meeting in West Virginia, I rode back with Carl Taylor to Washington, DC. On the way we got to talking about the impact of globalization on health, and the importance of getting mainstream decision makers to reexamine their assumptions. I suggested that to begin this process, we need powerful, indisputable examples of how specific free market policies are jeopardizing the health of millions. In answer, Carl told me of his personal experience in China, and the Health Ministry’s ongoing struggle to fend off the transnational tobacco corporations.

The Smoking Gun: Evidence of Globalization’s Negative Impact on Health

The impact of economic globalization on the wellbeing of humanity is much debated. Those who champion it—and even those who are trying to objectively understand its pros and the cons—often complain that the vehement protest against globalization lacks unequivocal evidence. There are, however, clear examples where the harmful impact of global economic policies is irrefutable.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), smoking is one of the biggest health problems of our times. While cigarette consumption has diminished in the US and to a lesser extent in Europe due to public education about its harm, in much of the world tobacco use is increasing. This is especially true in underdeveloped countries and Eastern Europe, where multinational tobacco firms have intensified their marketing.

The WHO states that smoking has become one of the biggest causes of death in the world. It predicts that if current global trade policies remain unaltered, by 2020, tobacco will contribute to over 10 million deaths annually. The biggest increase in deaths from smoking is predicted to take place in China.

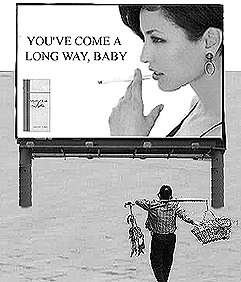

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Carl Taylor, then working with UNICEF, helped organize a national survey which showed that 60% of men in China smoked. By contrast, only 4% of women were smokers. Since then, with increased awareness of the huge societal costs of smoking, the Health Ministry has tried to reduce tobacco use among citizens, but it has been an uphill battle. The biggest problem has been the powerful leverage of the tobacco industry, coupled with a conflict of interest within the Chinese government. The tobacco transnationals, especially those based in the US, now target China as potentially their biggest and fastest-growing market. Their main target for new smokers is adolescents of both sexes, especially the potential market of young women. By promoting brands like “Virginia Slims” as status symbols of the modern, sexy, liberated, forever youthful woman, the industry aims to hook tens of millions of China’s women on tobacco. For many, this will be a death sentence. Despite this, influenced by powerful lobbying, international law generally supports the multinationals.

The Health Ministry has made efforts to oppose the promulgation of tobacco. Recently it prohibited smoking in public places (although this rule has yet to be well enforced). The Ministry also wants to outlaw both import and advertising of foreign tobacco products. But because of the temptation and pressures of an increasingly globalized market, such attempts have been stymied.

A complicating factor is China’s bid to join the WTO. The government feels compelled to join in order to sustain its current torrid rate of economic growth. But to do so, China will be forced to comply with the WTO’s trade liberalization rulings, including deregulation of tobacco import and advertising. The transnational giants will be allowed to promote and sell their addictive carcinogens in China using the tools of modern marketing to artificially stimulate demand.

Another complication is that many Chinese economists oppose a decline in tobacco consumption, because the biggest source of government revenue in China is the tobacco tax. To offset this, the health ministry has proposed a steep increase in the tax. Studies in several countries have shown that when the tax rises, cigarette consumption drops. The theory is that if China’s tobacco tax is doubled, cigarette smoking will drop by half, keeping tax revenue much the same.

Clearly, an increase in the tax makes sense in terms of both revenue and health. However, under the influence of the tobacco industry, the WTO has stipulated that China must actually cut its tobacco tax, to half of current rates. The resulting price drop will increase consumption with no corresponding increase in gov’t revenue. Thus, the Chinese population faces a health disaster.

Despite the magnitude of this upcoming tragedy, it is important to realize that this is not a singular event. The situation in China is just one example illustrating the general trend in which giant corporations in many industries continue to reshape the social and natural environment to maintain profitability. In this scheme, people are either resources or markets. This is not a rabid indictment, rather it is simply an observation based on countless documented incidents, and it is easily inferred from knowledge of the legal structure of corporations. They are designed to organize the conversion of “inputs” into profits, reward stockholders, i.e., absentee owners, and protect those owners and the management from legal responsibility for the consequences of business decisions (“limited liability”). So it is no surprise that such an entity, especially one which has grown beyond its managers’ ability to fully comprehend or control it, has no capacity or methodology with which to value human life and human needs. How to quantify the agony of men and women dying from cancer? How to factor in our collective loss of their dreams and companionship and talents? But life, it seems, does not compute.

How to Change the Global System?

Can such massive human sacrifice to the juggernaut of free-market development be avoided? To create a livable future will require at first reforms, and in the long run a sweeping transformation of the dominant globalized economic system, of the basic rules of the game. Such change will require a global movement of well-informed people.

To those of us who are committed to building healthy communities for a sustainable future, it is becoming apparent that action at the local level is essential but not enough. Time and again, we see the local advances we have worked for swept aside by global imbalances. Therefore many of us who have believed that Small is Beautiful and have devoted our lives to enablement at the local level, have had to revise our thinking. Though we recognize our efforts are but one more grain of sand, we feel we must actively take part in global efforts to transform the current inequitable and unsustainable model of globalized “development”.

The first step in working toward reforming—and eventually transforming—the unhealthy and unfair aspects of the global free-market system is to encourage awareness on the part of more people at every societal level. Many more people need to understand that the multitude of problems that society faces are much more inter-related than they currently suppose. They must understand how short-sighted economic policies affect their daily lives and endanger them and their families. They need the basic analytic skills to comprehend how corporate dollars purchase public elections, undermine democratic process, and put profit before people and the environment. With this new understanding, people around the world can join together to demand election financing reforms so as to gain a stronger voice in the decisions that affect their lives. They can mobilize to elect officials who put healthy and sustainable well-being as both a local and global priority.

Such an awakening to the realities of our time by a critical number of the world’s people will require a huge coordinated effort. The challenge is more daunting because the mass media are owned by the very corporations we aim to curb. Therefore it is essential that progressive NGOs, and anyone working toward sustainable change at the local level, also make a concerted effort to raise widespread awareness about the real nature of the obstacles facing us, and to build and participate in international coalitions for systemic change.

In sum, it is no longer enough to “think globally and act locally.” To reach a livable future we now must “think and act both locally and globally.”

Unless our immediate efforts to enable marginalized peoples or conserve endangered ecosystems at the local level go hand-in-hand with a longterm strategy to transform our dangerously inequitable and unsustainable global market system, our local endeavors will likely come to naught.

Nevertheless, local empowerment and action is still at the heart of equitable, sustainable development. Helping people in immediate danger find ways to cope with hunger, poverty, and crushing social structures necessarily comes before and along with long-term strategies to reform the overarching unfair system. But today, more than ever, we must keep the big picture in mind. When we evaluate coping strategies at the local level, we must continually ask ourselves to what extent this local coping strategy contributes to building healthier, more sustainable structures and policies at the national and international level. Without far-reaching macro change, hard-won local changes can be short-lived. Given the endangered biosphere, we cannot seriously talk about sustainable change at the community level without also pursuing structural change at the global level.

Politics of Health: Tools for Changing the World

HealthWrights, along with the International People’s Health Council and the People’s Health Assembly, aims to contribute to the exponentially expanding process of popular education needed to mobilize a critical number of people.

Such mobilization has begun, as evidenced by organized protests against corporate globalization in many parts of the world. We are concerned, however, that much of the confrontation of key players in the inequitable global economy—e.g., the World Bank—has been based more on shouting of slogans than on well-documented evidence. It becomes difficult to convince anyone who is looking for balance and objectivity.

This given, HealthWrights, in cooperation with the IPHC and PHA, has embarked on two interrelated projects to disseminate key information concerning the politics of health, especially as i relates to macroeconomic factors. These are:

Politics of Health Annotated Reading Lists

These categorized lists were started several years ago. We currently have three versions of varying length for different audiences, and we now hope to update and expand them.

We also ask those concerned with health and development issues to send us their recommendations of books, papers and articles for possible inclusion in the lists. Please include full references (title, author, publisher, date, address and website). If possible, also include an annotation of the content, specifically as it relates to the politics of health and sustainable development. An extract of key facts/statistics for the database would also be a help. (see below)

Politics of Health Database

This database is in its early stages. Our objective is to compile and present, in an easily accessible form, a wide range of accurate facts, statistics, and information relevant to the politics of health and sustainable development. It will function as a reliable source of statistics and well-documented facts to provide substance to lectures, classes, workshops, or articles concerning the politics of health and sustainable development, and designed to create awareness for action. At present this database is very much in its infancy. For it to become a useful tool, the compilation of facts and data must be a collective effort. You can help!

We are looking for volunteers to help assemble the database and the reading lists. We also need “information gatherers”, i.e., anyone who is willing to send in pertinent data they come across in their readings or research. Please contact us at healthwrights@igc.org. Help us make these reading lists and database into useful tools for change.

Also, if this article motivates you to support a global trade treaty to halt the spread of tobacco, visit the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control at http://www.fctc.org, or you can email Belinda Hughes at FCTCalliance@inet.co.th for instructions on how you or your organization can take concrete action.

A Hopeful Future: Bringing Health and Conservation Back Together

The following article was written by Kevin Starr for our Newsletter. Kevin has an exceptionally broad and holistic view of health, especially for a doctor. He is a board member and project mediator for the Mulago Foundation. As such, he has devoted the last several years to promoting the development of healthy communities, in which people in difficult situations learn to collectively care for their own health, improve their wellbeing, and protect the environment. The meeting of leaders from Mulago-assisted projects, described at the beginning of this newsletter, was organized by Kevin. He also played a key role in a gathering of Mulago-assisted programs at PROJIMO, in Coyotitan, Mexico, in May, 2001. In both these recent get-togethers, Kevin encouraged the project leaders to formulate a clear vision for working toward an equitable and sustainable future.

Like most doctors, my formal training had little to do with health. I learned a lot about diseases, but little about the things that prevent illness and create well-being.

It was only as I traveled to new places and encountered some wise teachers that I began to see that there was much more to health than simply treating disease. I learned about the importance of things like nutrition, poverty, and sanitation, and the role of less obvious factors like culture, public policy, and the ways in which communities can organize to bring about change. As my education progressed, it became clear that the medicine I’d been taught was only a small piece of the picture of health.

Helping people get to real, lasting health requires that we see the big picture. It takes an ecological way of thinking, a realization that everything is connected to everything else. For example, nutrition—the single most important factor in any individual’s health—is influenced by economic status, agricultural practices, cultural beliefs, educational level, weather, and the marketing practices of multinational corporations, just to name a few things. Narrowly focused approaches just don’t work.

Coming to a more ecological view led me to look at the relationship between the natural environment and human health. Again and again, I saw examples of how changes in the environment affected people’s health, usually for the worse:

-

Crop yields shrinking as thin mountain topsoil washed away.

-

Overpopulation forcing succeeding generations to divide their farmland into plots too small to support a family.

-

Devastating floods from deforestation.

-

Protein malnutrition endemic in coastal villages after over-fishing the local fishing reef.

-

Rivers and wells poisoned from mercury, oil, and pesticides.

-

Changes in forests helping to spread disease.

And of course, in every place I went, the effects of environmental destruction were harder on children than anyone else. It became more and more obvious to me that human health-especially the health of children-depends on the health of the natural environment. Conservation of our life support systems of air, water, soil, and local ecological balance forms the foundation of an effective and lasting approach to health.

Now, some people think that conservation is a luxury, something that only rich people can afford to think about. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Local conservation matters much more to cash-poor people living off their own lands. Rich people are insulated from their effects on the local environment; they can import food and export wastes. For example, the United States, the average piece of food travels over 1500 km. From where it is grown to where it is eaten. The water I drink in my city in California comes from lakes 300 km. away. The city of New York ships its garbage over 800km. to the state of Ohio. Cash-poor people can’t do that: they have to rely on their local environment for water, food, building materials, and other basic commodities. They can’t send away their waste products or afford expensive solutions to make up for environmental damage. They have to live with-or suffer with what they do to their local environments. So, more than anyone else, people without a lot of cash have to be conservationists.

While it is true that poor people have a bigger stake in local conservation, to be able to achieve conservation requires that you be able to think about the future-and to think about the future requires that the needs of today be met. People can’t think about the future when they are hungry, sick, impoverished or oppressed. Who could care about conservation when it’s not certain that there will be anything to eat tomorrow?

So I say to my friends working in health: “Lasting health depends on conservation.” At the same time, I say to my friends working in conservation: “Lasting conservation depends on health.” Human health and environmental health are forever intertwined-as two sides of the same coin, one cannot happen without the other.

People always list health issues as one of the things they’re most concerned about. Participatory community-based primary health care programs are an excellent place to begin integrating health and conservation, for several reasons. First, they provide an effective way to deal with the urgent problems of today and begin to achieve health with equity. Second, the participatory problemsolving methods create an opportunity to introduce environmental factors into discussions of community issues. Third, participatory community activities provide a forum for people to envision together the kind of future they want. And finally, the process of participating in well-designed community health activities can provide a model for making good decisions based on good information and then taking effective collective action toward specific goals.

It’s important for those working in both conservation and health to realize that the process of decision-making is central to lasting change for the better. People don’t destroy their environment because they are stupid or greedy; nor do they live in unhealthy squalor because they are lazy. It’s usually because they are acting out of desperation or on the basis of incomplete or misleading information. As a friend of mine working in international development says, “When people do dumb things, it’s usually because they had bad information.” Rarely do people have the opportunity to deliberately think about the future they want. People given the chance usually express the desire for a healthy environment-they don’t say “Hey, I think I’d like a future without any trees and with a river full of pesticides.” And even i people can express their vision of the future, they may not have an effective community process to solve problems and take action together.

Once people have these things—good sources of information, a vision of the future they want, and good community process—seeing and acting on the links between health and conservation become much simpler.

Examples of Connections Between Health and Conservation

Here’s an example of how obvious the connections can be. Suppose that a rural community surrounded by forest wants to address the issue of children’s diarrhea. The most important factor in preventing diarrhea is achieving a clean, safe water supply. The best way to ensure clean water is to protect the watershed area, which means leaving forest intact. This has the added benefit of helping conserve topsoil, which will help maintain good nutrition. Good nutrition is essential to helping children fight off the infections that cause diarrhea. And around it goes.

The connections can spin on and on. Here are some examples of how conservation and health have affected each other in some of the places that I happen to have seen:

In the Solomon Islands of the South Pacific, people were offered what seemed like huge sums of money from loggers for the right to cut down their trees. It seemed like a great windfall, but when it was all over, they found themselves much worse off than before. The resulting deforestation meant that instead of dripping off trees and soaking into the earth, the rains beat down directly on the exposed ground, carrying off topsoil and polluting the rivers. The ground became hard and rocky. Water ran off it in a torrent, causing devastating floods. Where the ground was flat, puddles formed and mosquitoes bred, leading to outbreaks of malaria. The loss of fish and birds from the ruined forests and rivers meant less protein in people’s diets. There was nothing to replace traditional forest-based livelihoods, something that contributed to cultural upheaval and alcoholism. In short, people were impoverished and sickened by selling their forest.

The Kayapo Indians of the central Brazilian Amazon also suffer from malaria. Rates of acute illness are 120% per year; everyone gets malaria and 1 of 5 get it twice. Studying the problem, it became clear that a number of factors are at work. Changes in the ways the forest is exploited may have shifted the mosquito population to a species more likely to spread the disease. Plastic trash scattered about collects rainwater and provides ideal mosquito breeding sites. Loggers and miners allowed into the area act as a continuous source of the malaria parasite. Whatever is done medically, any approach to rid the Kayapo of malaria will have to address these environmental factors. Dealing with malaria is leading to constructive changes in the way people are thinking about economic, cultural and ecological issues.

In a small village in the Fijian Islands, a medical survey team found shockingly high rates of high blood pressure and diabetes. Looming large among the suspected causes: destructive harvesting and fishing practices had destroyed the local reef as a primary food source. For this and other reasons, people replaced traditional foods with modern processed foods full of salt and sugar. Without good information, they had no idea these foods were bad for their health and no way to connect the destruction of the reef to their emerging health problems. In endless rounds of discussion, the village elders started laying a foundation for a return to the Fijian way.

In rural Costa Rica, vegetable farmers influenced by multi-national chemical companies adopted the intensive use of pesticides. The jungle insects proved very good at developing resistance to these chemicals. Farmers ended up using higher and higher amounts of pesticides, to the point where Costa Rican farmers were using more pesticides per hectare than anywhere on earth. With all these chemicals in the environment, the rate of poisonings skyrocketed. People knew the pesticides were bad—one farmer I met wouldn’t let his kids eat his own vegetables—but once the ecological balance had been lost, they felt trapped. Returning to organic farming methods and the introduction of new ecology-based methods of pest control offered farmers a way out of the mess they found themselves in.

For the San people of Botswana, supportive conservationists managed to address an important health issue in a way that led toward conservation. For centuries, the San had lived in the Kalahari desert, developing the skills that allowed them to thrive in unforgiving place. When their ancestral lands were confiscated for cattle ranches and fences were put up that stopped the migrations of game, the San lost their traditional way of life and became dependent on government handouts. The men, famed as hunters and trackers, had nothing to do. A depressed apathy set in; many turned to alcohol. Outside conservationists, thinking about both human and environmental well-being, came up with a number of integrated solutions. Presenting the results of good research, they persuaded the government to remove at least some of the fences. Advocating for the San, they helped them get their ancestral lands back in the form of parks where they could pursue some of their traditional activities. And after studying the potential of tourism, the project began training men as nature guides, using their hunting and tracking skills in a new way. Just a few months into the project, one could see a marked improvement in the morale of the villages.

From the Himalayan mountains of Tibet comes our final example. Living on a desert plateau at 4000 meters, people there have trouble finding adequate sources of fuel and are depleting the native juniper trees. Solar ovens provide an obvious answer, since Tibet has a high percentage of sunny days. As it turns out, though, there is an important potential health benefit of solar cooking. Traditional Tibetan kitchens are full of wood smoke, something that contributes to the high rate of respiratory infections there. A conservation solution is a health solution at the same time.

Start Integrating Health and Conservation

These examples demonstrate just a few of the connections between health and conservation. As community groups and committees work to address health issues there are a number of ways that they can bring conservation into the process. Here are a few suggestions (this is by no means a complete list):

-

Help your community imagine the future that it wants. As a part of your annual health surveys, organize ways to bring the community together for discussions of their vision for the future. As with the health survey, these discussions can lead to the establishment of priorities and work plans to begin making the vision a reality.

-

When addressing health problems, ask “What environmental factors are playing a role here?” It may be that the answers are obvious, or the question may provide a stimulus to gather more information.

-

Ask the question, “How are environmental changes that we notice affecting our health now and in the future?” Local people notice change and they usually have an opinion about what it means. Giving them the chance to express what they have observed and felt can lead to big changes in community awareness.

-

Collect and present good information. The best information is often local data, gathered by local people. It is immediately relevant, tends to be more complete, and most importantly, it is owned by local people. Other sources are outside experts, the world literature, and local lore and tradition. All of these have their place in decision making; the job of the committee member is to find good information and present it in useful fashion.

Summing it up

Sooner or later, human health depends on the health of the environment. To provide health care in a sickening environment is like oiling the door hinges while the house burns down. Health care is enriched and deepened by bringing in a conservation ethic: it brings optimism, as though we mean to get healthy and stick around for a while. A health care process that is by the people and for the people provides a natural way to integrate conservation into a long-term vision of well-being. Common sense, good information, and a bit of creativity can turn perplexing problems into a chance for a hopeful future.

Update on the PEOPLE’S HEALTH ASSEMBLY (PHA2000)

Good News! The new PHA website is at last up and running. Please visit http://www.phamovement.org. The new website includes newsletters and updates of follow-up action since the PHA2000 international event held in Bangladesh in December, 2000, and attended by 1500 people from 97 countries.

For a Critical Analysis of the PHA2000 Event, with suggestions for an even more successful follow-up, see the HealthWrights Newsletter from the Sierra Madre, #34. This is available at http://www.healthwrights.org.

The PHA has begun an email exchange intended to serve as a focal point for discussion and action. Although begun only recently, this email exchange already has demonstrated effectiveness in organizing its participants toward specific collective aims. For example, the exchange quickly disseminated information and assembled support for the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (see the article “Smoking Gun”, in this issue of the Healthwrights Newsletter). If you are interested in signing up to be part of this new PHA e-mail exchange, email the coordinator, Claudio Shuftan, at PHAexchange@kabissa.org.

The current secretariate for the PHA, worldwide, is coordinated by Qasem Chowdhury, whose address is:

GONOSHAHTHAYA KENDRA

HOUSE # 14/E, ROAD # 6

DHANMONDI, DHAKA - 1205

BANGLADESH.

TEL: 00880 2 8617208

FAX: 00880 2 8613567

EMAIL: pha_gk@citechco.net

A New Leg and the New Friends for the Professor

Which gives better results? Costly professional rehabilitation services in the United States? Or a small backwoods rehabilitation program run on a shoestring by disabled villagers? The answer depends on many factors, as the following example—which concerns my own brother—poignantly illustrates. It goes to show that money isn’t everything, at least for people who care.

On a dark, stormy evening in November, 1999, my sixty-seven-year old brother, Frederick G. Werner—better known as the Professor—suffered a tragic accident. As he left a church supper and began to cross the street on his crutches, he was run over by a passing car. One leg was mangled beyond repair, the other fractured in 20 places. At the hospital, his right leg was amputated slightly below the knee. The bone fragments in his left leg were set around metal rods inserted above and below the knee. Two months later a prosthesis was made for his stump and a full length plastic brace was fabricated to stabilize the other leg. A long, slow process of rehabilitation was begun to help him get back to walking. But for various reasons, things did not work out as planned. The whole process of providing a functional prosthesis and getting Frederick walking was fraught with an endless series of delays and frustrations.

The underlying problem was financial and bureaucratic. If he had been able to pay for private services, he would have been served more quickly and competently. But in the US, as increasingly elsewhere, health care is not a human right. You get what you can pay for. My brother is poor. Although he has a PhD in physics and was a university professor decades ago, he has long been unemployed, partly because of his hereditary disability (the same progressive muscular atrophy that I have but which has affected him more). Unfortunately, Frederick received no money from the driver’s insurance company. Witnesses say he stepped from between two parked cars directly into the path of the vehicle, so the driver could not react. The investigating policeman did not hold the driver responsible, so the insurance company did not cover medical costs.

Fortunately, being over 65, my brother was entitled to Medicare. And shortly after the accident, I and other relatives bought him a supplementary insurance plan. But unfortunately, the bureaucracy and delays in getting the services he needed led to to poor results. The prosthesis was essentially well-made but needed minor adjustments. But according to the regulations, the prosthetist was not permitted to make any adjustments until he got authorization from the case physician who was based at the hospital in Maine (and frequently, it seemed, on extended vacation). The physician, in turn, could not approve the adjustments without prior approval for Medicare.

This runaround and red tape caused delays of two months or more for adjustments that should have been completed the day the need arose, so my brother developed ulcerations and failed to progress. Because he was not progressing, the decision was made to discontinue his rehabilitation—Medicare, he was told, only covers rehabilitation for those who are showing improvement. A whole year went by and my brother was still unable to use his prosthesis well or to manage his self-care adequately. Complicating the picture was the pre-existing disability that caused weakness and severe contractures in his hands. In addition, he had a chronic prostate problem for which surgery had been delayed until he was up and walking on his prosthesis. In the meantime he used an indwelling catheter. It was always getting plugged up and had to be constantly flushed or changed. This made it very difficult for him to meet his basic needs. He was then living in a small trailer in the woods with winter coming on. To make things worse, in November, a year after his accident, the town’s sanitation officer condemned his trailer and ordered him to vacate it at once. He had no money and no place to go.

When I learned about this (I was in California at the time) I offered to arrange for my brother to go to PROJIMO, the small community-based rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers in rural Mexico. I had suggested this before, but my brother had always refused. He could not believe that poor disabled Mexican villagers could possibly help resolve his needs. But his alternatives had run out. A nursing aide from the hospital in Maine voluntarily accompanied him to Mexico.

For the PROJIMO team, my brother’s rehabilitation proved a big challenge. Within the first days, Marcelo Acevedo, the village prosthetic technician, took a mold of “Federico’s” stump and began to make a new prosthesis. Marcelo, whose legs are paralyzed from polio, has incredible skill matched only by his patience and good nature. Making a workable prosthesis for my brother was more difficult because of my brother’s preexisting disability. Also, whenever Marcelo or anyone else wanted to work with Federico he was always “occupied” with his urinary or bowel problems and other personal difficulties, which filled most of his waking hours. Nevertheless, with admirable patience, Marcelo persevered. By trying four different sockets and with dozens of adjustments, he managed to create a functional, comfortable prosthesis which my brother can easily attach and unattach himself, despite his disabled hands.

The team also helped my brother integrate into the community. He was tutored in Spanish by Julio Pena, a quadriplegic young man who runs PROJIMO’s intensive Spanish language training program for visitors from other countries (see the announcement). Julio devoted a lot of time, energy, and patience to this task. But “El Professor” would say jokingly that, like Reagan, he had “a Teflon mind: nothing sticks to it.” Nevertheless, Federico learned some daily basics of Spanish.

As it turned out, while he was at PROJIMO Federico helped to engender closer interaction between the rehabilitation program and the local community. The rehabilitation program recently moved from a more remote village (Ajoya) to the larger and more accessible village of Coyotitan, so it still does not have as close a bond with the community as it had in Ajoya. However, Federico helped build closer ties to the community by teaching English to a group of village children. In the early days of his teaching as many as 20 children would come eagerly to his classes. Federico would throw himself into his teaching with such energy and enthusiasm that the children would cling to each other in wide-eyed amazement. Sometimes my brother would become so carried away by telling wild stories in English, he would forget that none of the children could understand him. Julio, who has learned something of the art of teaching a second language from Sarah Werner, a cousin of ours from Cincinnati, did his best to share with el Profesor what he had learned.

My brother, who stayed at PROJIMO from December until June, has now returned to New Hampshire. On looking back at his experience in Mexico, in spite of the rustic conditions and sweltering weather, he speaks of PROJIMO as a “paradise” and of the disabled workers as “angels.” Above all, he praises Marcelo for having designed and built for him a prosthesis that works much better for him than the state-of-the-art limb made by a specialist in the United States. And it all cost only about 1/20th of what that specialist would have charged.

Marcelo was willing to work with me as a partner and equal in the problem solving process.

The Professor has come to realize that the biggest difference in quality of services is not so much a question of money or skills. It is a question of people to who genuinely care, and who are there willingly and cheerfully when they are needed. Without the sea of red tape.

Deja-vu

For me it was no surprise that Marcelo Acevado, the disabled village rehabilitation worker in Mexico, succeeded in making a well-fitting prosthesis for my brother when a highly-skilled prosthetist in the United States had been unable to accomplish this in nearly a year’s time. For me it was deja vu. Over ten years before, Marcelo had created highly functional plastic orthopedic leg braces for me which work better than the appliances made by specialists in the United States when I was a child. Marcelo succeeded when they had not because, rather than simply prescribing what he thought I needed, he was willing to work with me as a partner and equal in the problem solving process. The story of my childhood frustrations with specialists who would not listen to me, and the way Marcelo got better results by working closely with me, is told in the chapter called “Braces for David” in the book Nothing About Us Without Us, available through HealthWrights (please see the flyer on our publications).

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Emily Goldfarb |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Donald Laub — Interplast |

| Leópoldo Riboto — Mexico |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| Pam Zinkin — England |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Layout |

| Kevin Starr — Writing |

| Tim Mansfield — Editing, Production, Layout |

| Efraín Zamora — Software Consulting |

| Trude Bock — Proofreading |

| Marianne Schlumberger — Proofreading |

For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil, there is one striking at the root.

— Henry David Thoreau