Struggle for Social Justice and Fair Trade in Bolivia

I Picked the Wrong Time to Go to Bolivia

I had been invited to speak in La Paz at a national seminar on Communications and Disability with a focus on Human Rights, scheduled for October 15-16, 2003. On the 13th I flew from California to Miami and there boarded American Airlines flight #922 to La Paz. But the flight never landed in La Paz. Because of “social disruption” in La Paz and El Alto (the huge slum city above La Paz where the International Airport is located), the Bolivian government had prohibited all landings. Instead, we landed in the lowland eastern city of Santa Cruz, in the upper reaches of the Amazon basin.

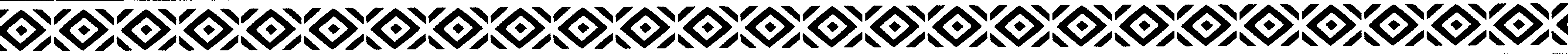

The “social disturbance,” of course, was rapidly escalating into the massive protest to oust the existing pro-US, pro-Free Trade government. Spearheaded by an indigenous movement (mostly of coca farmers) and miners from the surrounding countryside, the protest was soon joined by poor people of El Alto and the vast “septic fringe” of La Paz. University students and opposition parties—and even middle-class housewives banging on pots and pans—also joined in. At first the massive demonstrations were relatively peaceful. But when the president ordered the police and army to open fire with heavy machine guns, things became more chaotic, driven by what the New York Times described as the “Bolivian Peasants’ ‘Ideology of Fury.’” On October 14th and 15th—the most heated days of the protest—63 people were shot dead, among them women and children, including three infants in arms. Hundreds more were injured. Before it was over, more than 80 people were killed.

What Triggered the Protest?

The issue that sparked the massive protest was export of natural gas. But behind the gas lay a smoldering history of grievances related to an economic system—national and global—that increasingly favors the rich and marginalizes the poor.

Gas has become an explosive concern in Bolivia, partly because relentless deforestation of timber for export has made firewood for cooking increasingly scarce. Today most of the population, even in rural areas, is dependent on natural gas (propane in canisters). The unbridled growth of the timber industry that has plundered Bolivia’s forestland was abetted by the so-called Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to promote “economic recovery.” Since the mid-1980s the Bank and IMF have made big loans for the “development” of industries that export the country’s marketable natural resources, including timber. (SAPs put pressure on poor countries to increase production for export in order to generate dollars to make payments on their enormous foreign debts.)

The story of natural gas parallels that of timber and of tin. Bolivia has one of the largest natural gas reserves in the world, second only to Argentina. With the demise of the tin industry, natural gas has become the country’s leading export.

The recent angry protests in La Paz emerged to oppose the plan of Bolivia’s President, Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada (known to Bolivians as “the butcher” and nicknamed Goni) to vastly increase the export of natural gas, to be transported through a proposed 5 billion dollar pipeline to a Chilean port. The gas was to be exported to the US and Mexico at an incredibly low price of US $5 per cubic meter - while maintaining the current price within Bolivia of US $60 per cubic meter. In sum, impoverished families in Bolivia would have to pay 12 times as much as the export price to rich countries! (To the peasants in Bolivia, the poorest country in Latin America where 51% of the people lack electricity and the average income is US $3 per day, even Mexico seems like a rich country.) The protesters see this disparity in pricing as outrageously unfair. They demand Bolivia reduce the price of gas to its citizens to equal the export price, and that the gas be used for local development, not foreign profits.

High Price of Gas Reduces Health

The protesters see the current high price of gas for domestic use not only as an economic problem for the poor, but also as a health problem. The legal minimum wage in Bolivia is about 2 US dollars per day, so little that millions of families cannot adequately feed their families. Over 60% of Bolivian children are chronically undernourished (stunted in both bodies and minds) with an under 5 mortality rate of 77 per thousand (nearly one in ten!). Aggravating this situation, unemployment in Bolivia is around 25%, underemployment over 60%. As the main cooking fuel, gas is essential for preparing the staple foods of the poor: maize, beans, rice, quinoa (amaranth) and yucca (cassava). Money that families must spend on fuel reduces what they might otherwise spend on food. Thus the high gas price contributes to child undernutrition, which in the long run is a setback to the development of the nation.

It is also, assert the protesters, a crime against humanity. Having enough to eat is a fundamental human right, declared in the International Rights of Children. Pricing an abundant local resource out of reach of the people, and thereby increasing hunger, violates that basic right.

But why, then, doesn’t the Bolivian government follow the humane and health-protecting option of selling its natural gas at an affordable price to its own citizens, rather than exporting it at a giveaway price? The revenue, some argue, could be as great or greater, and the people healthier. Why should the president risk social unrest and (as it turned out) his own overthrow, when a more popular, more health-conducive solution seems so obvious? I asked these questions of a small group of Communications students of Cumbre University in Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Profits Before People

The students gave me several reasons. One, they said, was that Bolivia’s [now exiled] President Sanchez was on the dole from the US government. He was strongly supported by transnational corporations and beholden to the International Financial Institutions (World Bank, IMF), which pressured him to export gas at a “competitive” price. Another reason, they said, relates to Bolivia’s huge foreign debt. The debt must be serviced with dollars, not an unstable local currency. Sale of gas to citizens, no matter how large, doesn’t generate dollars. Hence the Bank’s “conditionalities” require that debt-burdened countries “adjust” their economies toward export. If that means less food or fuel to meet the people’s basic needs, too bad. It’s part of the cost of international economic development.

This strategy for servicing foreign debt has been imposed on many economically struggling countries in exchange for loans. In the past the World Bank and IMF have insisted that such “temporary hardships for the poor,” are necessary for long-term economic growth. However, as UNICEF has pointed out, such “short term austerity measures” translate into long-term consequences for millions of children, namely stunting, disability and death.

‘Adjustment With a Human Face’—But No Structural Changes

The World Bank—partly in response to strong criticism by international “watch-dog” groups—asserts it has now reformed, adopting what UNICEF has called “Adjustment with a Human Face.”

The Bank has recently revised its mandate (less than its practices) to prioritize “eradication of poverty.” Some of its “Poverty Reduction Programs” have some excellent features at the community level (as I witnessed in Andhra Pradesh, India; see our Newsletter # 48).

Yet with rare exception, these community-level programs meticulously avoid demanding the macro-economic policy changes that would allow poor countries to restrict export and regulate import so as to allow better use of their local resources to meet their people’s basic needs. Rather than tackle the entrenched systemic inequities that drain poor countries of their resources, the Bank opts to help poor people in poor countries fight poverty by promoting “local cost effective projects” such as “micro-enterprises.” Using all the old revolutionary jargon, it designs “self-help” initiatives to “empower the people” to “pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.” Sometimes these “self-reliance engendering” projects seem to work, at least on a limited scale. But faced with the global pandemic of falling wages, rising unemployment, and routine downsizing of corporate industries, too few destitute people can afford even sandals, much less boots with which to pull themselves up by the straps. True, a handful of the more innovative poor folks may benefit temporarily from these self-help income-generating ventures. But as their numbers grow, competition with one another tends to drive down prices. In any case, the vast majority of the poor—including as ever the most vulnerable—still fall between the cracks. And as ever, the root causes of persistent poverty—many of which lie in the increasingly deregulated and globalized market system—remain largely unaddressed.

Despite all the back-patting rhetoric of poverty alleviation, the dominant, inequitable paradigm of economic development is still determined, undemocratically and largely behind closed doors, by a relatively small but extraordinary powerful ruling class.

Small wonder, worldwide, the gap between rich and poor is growing by leaps and bounds! In Bolivia, 20% of the people receive 49% of the income, while the poorest 40% make merely 13%.

Tension with Chile

The gas issue in Bolivia is also rooted in national—and increasingly indigenous—pride, as well as historical tension with Chile. The plan of President Sanchez and the transnational corporations to run a pipeline to a Chilean seaport prodded an old wound. Many Bolivians see Chile as “the enemy,” not to be trusted. This antagonism stems from an old dispute between Bolivia and Chile over national boundaries. In the mid 19th Century the British government helped Bolivia build a railway line from La Paz to Antofagasta, a port on the Pacific Ocean, then part of Bolivia. The railroad would expedite export of tin and other natural resources to England. But after the railway was completed, in 1879 Chile invaded and took possession of the coastal territory, leaving Bolivia landlocked. The British government backed Chile, in part so that Chile would sell the rich coastal resources of seabird guano to England at greatly reduced prices. As a result, Bolivia lost all access to the sea, and to this day remains beholden to Chile for access to shipping ports. It also must pay Chile duty for use of what was its own railroad. This travesty, Bolivians assert, is one reason why Chile has prospered through international commerce, while Bolivia remains the poorest, most foreign-aid-dependent country in Latin America. The open wound and resentment persist. As with the railroad, most Bolivians are convinced Chile will heavily tax the proposed pipeline, further widening the gap between rich and poor, and deepening the weaker country’s dependency on the drain of international “free trade.”

The natural gas proposal is the latest in a long series of policy shifts and inequitable economic adjustments that the poor of Bolivia say have increased their hardships. Under strong international pressure, the Bolivian government—like economically strapped nations the world over—has been aggressively privatizing its national industries and public services, including mines, electricity, telecommunications, airlines and water. One privatization that triggered a huge nationwide protest a few years ago was the sale of Bolivia’s national oil industry to a private corporation based, of all places, in Chile! Old resentments exploded, but the protest was soon squelched.

Some such protests, however, have succeeded. When a previous president took steps to privatize the railroad system, tremendous popular resistance forced the government to give in, at least for the time being. And when water distribution in Cochabamba was privatized and handed over to a subsidiary of the U.S. company Bechtel, the uprising in response forced Bechtel out and the government was forced to renationalize the water. Today Bechtel is suing Bolivia, South America’s poorest country, for $25 million, for profits it wasn’t able to earn as a result of the public uprising.

Nearly everyone I talked to in Bolivia was sympathetic to the October uprising, and openly hostile toward President Gonzalo Sanchez. As by far the wealthiest man in Bolivia, el Goni was already deeply resented by the poor majority. He and his family made their fortune in gold and silver mining. Many say he has an income of more than 600 million Bolivianos a year (about 80 million dollars).

Low Intensity Democracy

I asked my hosts in Santa Cruz: What percentage of the population backs President Sanchez? They estimated 20%. Then I asked: “If Bolivia is a democratic nation, how did a man with so little popular support get elected?”

I got many answers. Some laughed at the suggestion Bolivia is democratic. Others noted that “Goni” has been strongly backed by the United States and transnational corporations. He certainly has the leverage to sway the corporate-owned mass media, which systematically brainwash the citizenry. Others pointed out that Goni won the last election with only 22 percent of the vote, just one percent more than Evo Morales, head of the National Coca Growers Federation. By pulling several of the smaller parties into an ad hoc coalition, Goni was able to sneak the lead.

One of the professors reminded me that the United States carefully oversees the political environment of Bolivia, and will take the necessary measures to keep in power the party that best serves its purposes. Presidential elections in Bolivia take place every 5 years. Evo Morales, a self-educated indigenous Aymara, is the highly popular candidate of the “Towards Socialism Party” and head of the prestigious Coca Growers Union. He is also a thorn in the side of the White House in Washington. If elected president, he promises to reverse privatization of public services and utilities, to increase minimum wages, and to regulate foreign investment so as to better serve human needs. But what angers the White House most is that Morales stridently opposes the forthcoming Free Trade Agreement of the Americas, which the Bush Administration is pushing no holds barred.

From the perspective of the US power structure, a pro-people candidate such as Evo Morales is as dangerous as Fidel. Informed people I talked to are convinced that if Bolivia’s elite need help in sabotaging the democratic election of Evo Morales, the US will take the lead, using whatever overt or covert action is needed to neutralize him. I was reminded how the US has effectively eliminated other democratically elected presidents in Latin America, including Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 and Allende in Chile in 1973. Informed Bolivians have little doubt that the recently attempted overthrow of the “poor people’s president” Hugo Chavez in Venezuela was kindled by the transnational oil industry with help from the CIA.

I was told by university professors, in fact, that Bolivia’s Ministry of Interior has two permanent CIA “advisors,” and is sarcastically dubbed the Bolivian “Departamento de Inteligencia” (i.e. Bolivia’s CIA).

Does Bolivia Have a Free Press?

Does Bolivia have a free press? Constitutionally, yes. But during the recent protests, any media that dared to objectively report on government abuse were subject to heavy-handed censure. Or worse. The government was especially aggressive in suppressing radio reports. Radio is the primary means of communication to the nation’s poor majority. In the first days of escalated protest, two major stations were “bought off” (their silence paid for) and one radio station in the highlands was dynamited. (I learned this from a friend in La Paz who works in communications and has links with a non-government watchdog group called the Defensoría del Pueblo. (My friend and his colleagues worked round the clock trying to keep news communications open and uncensored.) Even an Internet news board—a critical source of full and accurate political reporting in Bolivia—mysteriously ceased to function. Several newspaper offices were raided and closed down.

I was still in Bolivia as I wrote this section:

It is now October 16. Yesterday, on the 15th, the protest was largely confined to La Paz and El Alto. But today it has spread to other parts of the country. Because I could not get to La Paz and because the National Seminar I was to speak at there was canceled, the organizers of the Seminar made stop-gap arrangements with colleagues here in Santa Cruz for me to speak at two local private universities. I willingly did so. But attendance was far less than anticipated because public roads were blocked by protesters and many students were afraid toventure onto the streets. Others joined the march.

In Santa Cruz, so far, the demonstrations have by and large remained peaceful and police have not been overly abusive. Nevertheless, many shops and restaurants have remained closed, their owners fearful. (In previous protests in Santa Cruz, events have sometimes gotten out of hand: shops vandalized and looted. Some shopkeepers lost everything.)

I asked my hosts at Cumbre University if they thought the nationwide protest would be effective in changing the government’s position. They shook their heads, stating that “El Goni is stubborn as a mule. Instead of yielding to popular demand, his typical response is to step up police and military repression.” Which he did.

For a while, however, the President indicated he would consider a compromise, and the protestors in La Paz stood their ground more peacefully. But it soon became clear that the Goni was just trying to buy time, and had no intention of significant policy change. So the protestors revised their tactics. One large group started a hunger strike. This mobilized yet wider resistance and renewed demands. The President declared that all who took part in the protest were drug traffickers and seditionists. Violent repression was stepped up. But it proved counterproductive. The gas protest escalated into a demand for the President to resign. Which on October 17 he did. Fearing for his life, he fled La Paz. It was rumored that he secretly took refuge in Santa Cruz. Then he turned up in exile in Miami.

Goni’s gone. Now what?

What remains to be seen is if and how the US will intervene in the fast evolving politics of Bolivia. If the Bush Administration thinks that the opposition leader, Evo Morales—whom it regards as a threat to Free Trade and its holy War on Drugs—might win the next presidential elections, will the hawks in the White House take “preemptive” action? Currently in El Salvador, for similar reasons, the CIA is said to already be working hard to undermine the pro-people, anti-free trade agreement FMLN candidate who shows a strong lead in the polls. And in April of 2002, when Hugo Chávez, the democratically elected president of Venezuela, was briefly deposed by soldiers supported by an elite and the media, the US quickly recognized the coup on the false pretext that Chávez had “ordered fire on his own people.”

Latin America has become the battleground for the economic struggles of the present. To Ecuador’s ousting of Jamil Mahuad in January 2000, Peru’s overthrow of Alberto Fujimori in November of the same year, and Argentina’s ejection of Fernando de la Rua in December of 2001, we now add Bolivia’s forcible rejection of Gonzalo Sanchez.

But we must not kid ourselves. Surely, “preemptive regime change” did not start, nor will it end, with the Bush Administration. The US military-industrial complex has a long history in Latin America and around the world of covertly undermining, or if necessary, forcefully overthrowing, governments it considers a threat to US business interests and global dominance.

Now Goni’s gone. Despite his resignation, few people I talked to in Bolivia were optimistic that any major socio-political change will happen in the near future. Bolivia is just one small struggling country within a globalized power structure that puts profit before people.

Strength through unity? Perhaps the most likely chance to significantly address (or at least regulate) the structural causes of poverty lies in the efforts of poor countries to come together in solidarity. Working together and speaking with one voice will strengthen their demand for international policy based more on human and environmental need.

The most encouraging, if controversial, example of such Third World strength-through-unity took place at the global summit of the World Trade Organization in Cancun, Mexico in September, 2003. There an ad hoc coalition of weaker states succeeded in blocking, or at least postponing, the attempt of the rich industrial countries to pass further international laws that favor rich countries and transnational corporations at the expense of the poor. The poor countries joined forces to successfully block an accord that would have sanctioned the subsidized export of rich countries’ agricultural surplus, arguing that such subsidies make it harder for poor Third World farmers to compete, thus deepening poverty. The industrial powers were, for the first time, thwarted by this united resistance by the economically weaker nations, a critical first step toward healthier global economic policies!

A poor country like Bolivia, acting alone, stands little chance of successfully challenging the unjust international policies of powerful industrialized nations and the international financial institutions. Nor is it likely, on its own, to bridle the exploits of unscrupulous transnational corporations.

But through “globalization” from the bottom up there may yet be hope. In unity lies strength. Cancun was a groundbreaking first step.

Note: Additional information and discussion on Bolivia can be found in our web site: www.politicsofhealth.org. This includes a powerful letter by Evo Morales, in response to scathing accusations against him by the newly exiled ex-president Gonzalo Sanchez.

Bolivia: Two Worlds

When I arrived in Santa Cruz on October 14th, 2003, I was repeatedly warned not to go onto the streets alone, especially at night, because of the ever-present danger of being pick-pocketed or assaulted. But currently (during the proliferating anti-government protests) the danger was so great I should not venture onto the streets at all. But I wanted to get the feel of the place and times. So I took several long walks through the inner city neighborhood where the rather scruffy hotel I had chosen was situated. Walking through the bustling inner city I began to feel that I was moving through two worlds: intercalated but radically separate. The haves and the have-nots. From living in Mexico and traveling through many Third World countries I am used to the stark contrast of the down-and-out living in the shadow of affluence. But somehow on the streets of Santa Cruz, the polarity was even more striking.

On the one hand, the streets of the city center are lined with stately shops and swank restaurants. Grandiose plate-glass store fronts displaying the most seductive and costly of materialistic gadgets, elegant furniture, luxury goods and high-class appliances. The people who frequent these shops are elegantly dressed, pale-faced and dangerously overweight. They have an air of ownership and empty authority. On the other hand, in make-shift kiosks cluttering the sidewalks and gutters are the have-nots, most of them darker and with more “Indian” features. They are notably shorter in stature than the “haves,” who carefully step around them. These “wretched of the earth” are selling knickknacks, grilling cobs of corn, peddling tamales wrapped in banana leaves, repairing shoes, or sewing clothes on the curbside. Or simply begging. A number of the women, stoop shouldered, babies slung against their backs or chewing at their breasts, are dressed in cheap factory-made imitations of the traditional Indian garb. But the men, with rare exception, are shabbily dressed in second-hand Western clothes: carefully patched trousers and faded T-shirts sporting once-colorful logos of Pepsi, Scooby Doo, Rambo, and Burger King, or the beloved Nike swoosh.

Virtually all of the shops, diners, and lottery outlets are equipped with huge television sets—many over four feet across—in what seems a very macho “Mine’s bigger than yours” competition. Proudly facing the street for world viewing through the expansive plate glass, the Tvs invariable project Hollywood movies, one more violent than the next, interrupted only by tantalizing advertisements (many of which also depicted savory bits of violence or insensitive humor where a stereotypic scapegoat is trashed or made a fool of). Invariably, scores of noses press against the pane, as a motley collection of the “have-nots” and “ne’er-do-wells” fill their empty bellies on this fare.

Not surprisingly, each of the stores has its own private Terminator [security guard] standing languidly by the entryway, Uzi slung over his shoulder. It was clear to me that for the underclass there is no existential entry into this vapid world of plenty that surrounds them. Yet at the same time, no exit. It struck me as a stage set for despair, frustration, and violence: the so-called “culture of outrage.” That the protest of the down-trodden at that very moment I walked through the streets of Santa Cruz was building like a tsunami, was utterly understandable and predictable. Can’t the “haves” see that they are building their own petard?

But then it occurred to me that both the “haves” and “have-nots” are victims of the same tragic comedy: the inhuman system that is somehow out of control, like a global cancer, running its own pernicious course. In its voracious thrust, life, beauty, joy, sexuality, even love have been trivialized and squandered. Everyone—from the obese to the famished—is groping, like Tantalus, for something out of reach. All in the same cage of mirrors.

What has happened to the concept of Liberty, of Freedom, of Equal Rights, of Fair Play, of all those stone-carved values of which the U.S. still so vainly boasts?

Everyone, it struck me, is in one way or another looking for a way out. The great escape. I was puzzled that in Latin America’s poorest country, the highway from the airport to the city is lined with amusement parks, golf courses, pony rides, video-game arcades, ice-skating rinks, etc., each garishly competing with the next. Mickey Mouse, Loony Tunes, Star Wars, the Matrix: the most seductive of US Great Life of Illusion; the Promised Land, the pot of gold at the rainbow’s end. (I believe it was no accident that the movie on my American Airlines flight both to and from Bolivia was “Bruce Almighty,” one of the most banal, spiritually trivializing Hollywood flicks ever filmed.)

Santa Cruz Bolivia, suburb of New York City! As a kind of grotesque symbol of the whole schizoid scene, there it is! Standing imperiously atop the sales hall of a huge used-car lot on the outskirts of Santa Cruz, silhouetted priapus-like against the night sky, grandly illuminated by gyrating floodlights, is a great gray-green greasy replica New York’s famous Statue of Liberty.

“It’s just a crude copy,” my host told me apologetically. Just a copy! But I found myself asking: What has happened to the concept of Liberty, of Freedom, of Equal Rights, of Fair Play, of all those stone-carved values of which the United States still so vainly boasts?

Even in the United States, for all its wealth and surplus, one out of 5 children often goes often hungry and 43 million people lack health insurance. Child mortality for Blacks is double that for Whites. Life expectancy in Washington DC is lower than in Cuba, which struggles along despite the US embargo on 1/20th the GDP per capita. Yet welfare for the needy has been steadily reduced, even as military expenditures increase. The rich get bigger and bigger tax breaks. And giant corporations are subsidized by taxpayers to export their surplus to poor countries at below-cost prices with which subsistence farmers cannot compete, thus sowing the seed of destitution, prostitution, and the pandemic of untreated AIDS.

Yet the US, self-appointed policeman of the World, is proudly exporting its inequitable mercenary model of development around the globe. Stopping at nothing, it has a long history of destabilizing equity-seeking governments or rigging the overthrow of those small, struggling countries that have dared try to prioritize need before greed.

Statue of Liberty. Statue of Sadam Hussein. Two worlds? Or one world? It is indeed time for régime change. Time to change the regime—that has the most dangerous weapons and policies, from nuclear bombs to the neocolonial market system—that endangers the health and sustainability of humanity.

Bolivia cannot make it alone. Nor can any of us. To work for peaceful and lasting change, the world’s people—all of us, from the shoe shiners to the boot lickers, from potato-pickers to potentates—need to be more fully and accurately informed, and to find a collective voice. We need to rediscover the joy of working—and if necessary dying—for the common good, while at the same time celebrating diversity and the freedom to love.

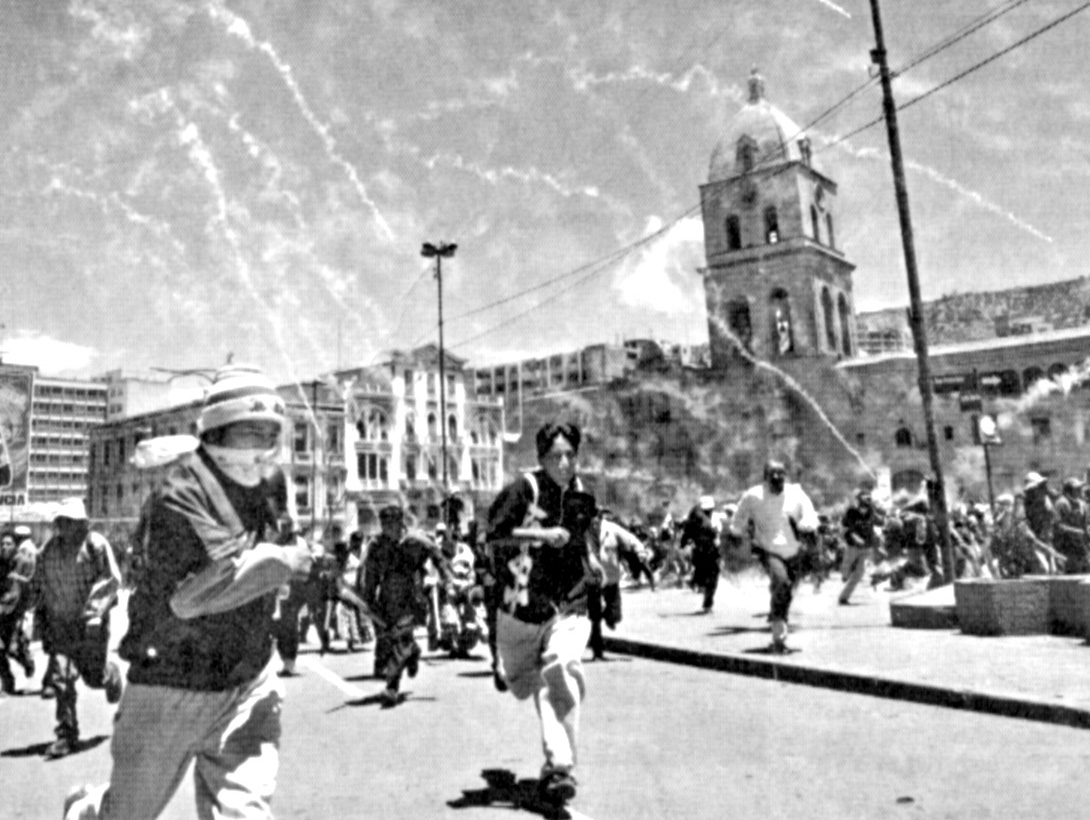

Scraping a Living in Bolivia’s Outback: From Tin to Cocaine to Orchids

Uncle Sam has poured huge amounts of money and military equipment into its War on Drugs in Bolivia. US military outposts are sprinkled through the countryside.

But Bolivia was not always a major producer and trafficker of cocaine. Chewing coca leaves and drinking coca tea are ancient traditions among the indigenous people, like drinking coffee in the US, and is probably healthier than drinking coffee. As Bolivians are quick to point out, the chemicals needed to convert coca into cocaine are largely imported through the international market. And the growth of the illegal drug industry in their country is a response to the huge demand of the world’s biggest consumer of illicit drugs: the US.

But there is another reason why Bolivians blame the United States for the expansion of coca farming in their country. Tin. In the inhospitable mountainous reaches of central Bolivia where coca growing has flourished, the main source of income for local people used to be tin mining. Bolivia has one of the world’s largest reserves of tin. Export of tin was once the country’s biggest source of revenue. Work in the tin mines was backbreaking and the pay miserable. But thousands of unschooled, socially marginalized people depended on the tin mines for their subsistence.

During World War II, Bolivia supported the Allies by supplying vast amounts of tin to the US at very low prices. Tin was essential for production of weapons and military equipment. By the time the war ended, the US had a huge surplus of tin. It not only terminated its purchase of tin from Bolivia, but began selling its vast surplus on the international market, at tax-payer subsidized prices. So it was no longer profitable for Bolivia to keep mining its tin.

From one day to the next the tin mines were shut down, throwing many thousands of people out of work. Few other jobs were available in that remote mountain area. Desperate, people looked for any alternative to feed their children and keep the wolves from their doors. A few innovators used their meager severance pay to rent or buy a small plot of land, and began to plant coca for the clandestine market. (Controlled growing of coca for traditional local consumption is still legal in Bolivia.) Then everyone jumped on the bandwagon. That is how Bolivia became a drug-producing country and threat to the well being of the people of the United States.

In sum, US demand for tin was replaced by US demand for drugs. Bolivia adapted accordingly. Supply and demand.

In part at least, it appears that the War on Drugs in Bolivia has been a success. The World Bank and USAID have helped former tin miners cum coca farmers earn a living with alternative crops for export. Two of the most heavily promoted export crops are orchids and roses. Both government and private farms have been set up, as well as a few worker owned cooperatives, in which over 200 species of native and hybrid orchids are now grown for export. Most workers barely manage to eke out a living. But at least they don’t have to worry about raids by the soldiers or poisoning by cancer-causing herbicides sprayed by US helicopters. Coca production in Bolivia reportedly has greatly declined.

Social scientists and nutritionists in Bolivia are critical that the World Bank and USAID put so much effort into substituting coca farming with growing flowers for export, rather than by helping the farmers successfully produce nutritious food crops for the local market. Malnutrition remains a big unresolved problem. But as in the case of timber and natural gas, it appears that the Bank and USAID’s choice is influenced by its policy of rescuing the northern banks rather than the local people, of promoting production for export in order to generate dollars for servicing foreign debt.

After all, the illegal drug trade is a big part of the global economy. Fiscally, it is the world’s second biggest industry, after weapons. I don’t have the figures for Bolivia, but for Mexico, as far back as the 1980s the US State Department estimated that 70% of the money Mexico paid annually to service its US$110 billion foreign debt came indirectly from drug money. So it is understandable if the Bank and USAID want to replace Bolivia’s cocaine industry with another export-income generating crop, one that will provide Bolivia with US dollars to export as debt, rather than local income that could remain in the country to help alleviate poverty.

Politics of Health Project Update

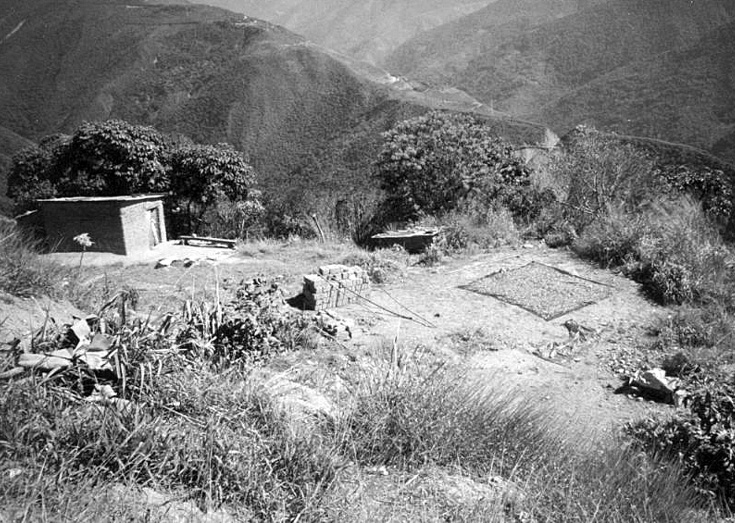

Launched in October of 2002, the Politics of Health Knowledge Network (www.politicsofhealth.org) is designed to be an online resource for individuals looking for information on the political, structural, and institutional factors affecting the health of people and populations. The Knowledge Network aims to illustrate the linkages between these factors, and how they fit into the larger picture.

The politics of health (POH) website attempts to clarify the interconnections between the broader issues (for instance ‘Pharmaceuticals and AIDS’, or ‘Free Trade and Hunger’), and presents the information in an easy to read format. Drawing from a multiplicity of sources, our editors carefully select articles, pictures and graphs that bring the issues to life and help writers and researchers access the critical reports and information they need to affect health policy.

Although the volunteer-driven website is in its infancy, it has already generated a lot of interest from academia, non-profit organizations and from all over the world. We are encouraged that all this interest has sprung from just the prototype website, featuring just a few major topics that serve as a model for further development. The scope of the website is indicated in the range of topics (see box) to be covered on the site.

Politics of Health Topics

- Arms & Military

- Democracy

- Disabilities

- Diseases

- Education

- Environment

- Ethics

- Food & Hunger

- Global Economics

- Global Health Organizations

- Health Services Sector

- Humanizing Institutions

- Killer Industries

- Labor

- Population

- Regions

- War

- Water

- Women’s Issues

Collaborative Focus

Three editors are managing the content and planning the scope of the site for the upcoming year, while a large technical team is working on making this resource an easy-to-use collaborative tool. Screens such as the one you see here, will encourage our readers to participate in the development of the site. We will be inviting article submissions directly into the appropriate section on the website, where our editors will review them for posting.

HealthWrights has developed and provided a Politics of Health Reading List for many years to assist health workers and activists to develop a strong understanding of the external factors affecting their work. David Werner has spearheaded this project as an adjunct to his self-help health and disability publications. Publishing on the Web provides us with the opportunity to work more collaboratively with more like-minded groups and individuals from around the world, and hopefully accelerate the development and dissimination of important articles and ideas. The Knowledge Network provides a forum for sharing in-depth articles as well as more up-to-date information to a wider audience. Attracting activists, researchers and authors, the site aims to provide an online interactive community for analysis, positive action and alternatives.

New Updated Site Coming Soon

The next version of the site is under development, and it will soon emerge with a whole new look and many new features that will facilitate participation and communication between our readers. We encourage you to check the site often, and to contribute articles, sign up for email updates and participate in discussion forums. A great deal of our attention is focused on producing a site that is well-organized and easy to use, and that will help researchers and activists in developing new materials to promote more health-affirming policies. In particular, the site is being designed to develop an active community that will focus attention on the most pressing issues, and improve the effectiveness of all of our work.

JOIN IN! We Invite Your Participation

If you are a researcher or writer, and are passionate about any related issue (see our topics list) please send us an email.

We are currently seeking to attract more financial support to offset our costs. For donations, please see the attached flyer or visit us online at: www.politicsofhealth.org. We welcome your feedback and encourage you to spread the word about the Politics of Health Knowledge Network!

CONTACT INFO: Send your comments, questions and suggestions by email to: comments@politicsofhealth.org

Address: Politics of Health C/o Healthwrights c/o Jason Weston, 3897 Hendricks Road, Lakeport CA 95453 USA, info@healthwrights.org .

The Politics of Health Team

We have enlisted an outstanding team of accomplished Bay Area computer professionals who are guiding this effort as volunteers. Many thanks are due to:

TECHNICAL TEAM

Manu Gupta - Technical Manager

Sanil Pillai - Senior Developer

Priya Venkitakrishnan - Sr Developer

Yanping Liao - Senior Developer

Gary Gibson - Technical Researcher

Deepa Pai - Technical Researcher

CREATIVE TEAM

Jarrod Fischer - Creative Director

Anupama Gurumurthy - InteractivityDeveloper

Project Manager: Shefali Gupta

Humanizing Institutions: A New Topic for the Politics of Health Knowledge Network

A new topic has recently been added to our site: “Humanizing Institutions.” Wow. That sounds dull. Originally we were going to call it “The Politics of Everything You Never Dared to Think About,” but we decided we had to tone it down a bit. Still, under this innocent-sounding title we plan to deal with some exciting and volatile ideas that could, if implemented, change the world in which we function day-to-day.

This new section will complement the web site’s existing emphases on physical health and the health of societies with careful consideration of issues related to interpersonal health. We will also more explicitly include within the scope of “politics” our day to day living in families, schools, work places and other social groups.

Perhaps the set of shared values that should guide our common efforts on local, national and international levels is best captured by the term “democracy.” In the narrow sense, democracy means rule by the people. Alex Tocqueville, a shrewd observer of American life, was generally sympathetic toward the fledgling experiment in democracy that he observed. Even so, he warned of a danger. Majority rule can itself become a form of tyranny. It is for this reason that the principle of rule by the majority must be balanced by the realization that the rights of individuals and minorities must be protected. It was this understanding that undoubtedly led the framers of the constitution of the United States to amend the constitution with the bill of rights.

These considerations suggest that a broadened understanding of democracy needs to include recognition of the importance of several sub-values:

-

Participation in decision making within the social spaces one occupies.

-

Self-determination in the pursuit of happiness.

-

The dignity and worth of the individual.

-

Civil liberties.

The unifying theme in this section is this: if the world is to survive as a place fit for human habitation, the ordinary institutions within which we live and do business must themselves become democracies. Democracy is a powerful and transformative idea that must be brought into our families, our places of work, our schools, our religious institutions, and our health agencies. Democracy, as we define it below, mandates that social life be guided by two principles:

-

the full participation of everybody in formingthe goals and policies that shape the life we share, and

-

an appreciation of minorities, and people withs pecial vulnerabilities, and protection of their rights.

Humanizing Institutions

There appears to be an emerging consensus across the political spectrum, and across national boundaries, that democratic values should provide the agreed upon guidelines for our common efforts. We see these values reflected, for example, in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Unfortunately these values are regularly set aside when they appear to be impediments to more pressing concerns.

The policies and procedures that embody the goals and dictate the organizational structures of the major institutions in a society ideally should reflect the fundamental values of that society. When the institutions of a society conduct their business in a manner that is flagrantly at odds with its values, serious ethical and functional problems arise. Lack of harmony between values and practices in a society poses serious threats to the personal and interpersonal well being of its members.

There are undoubtedly many people who feel democratic values should hold sway in the political sphere of life, but that they are not relevant for the business, educational, religious, governmental, law enforcement, and social service organizations that carry out the day to day business. It is argued that democratic ideals are nice in theory, but that they are not efficient in practice. Throughout this section we will be looking at examples that challenge this pessimistic assumption. We will argue that by relying on democratic institutions we will be able to educate our children better, provide for a higher level of health care, deal with those who deviate from society’s norms in a more rational, humane, and effective manner, and create and distribute the goods and services in society more effectively. Democratic values should and can be made to inform the interactions between people in all spheres of life. Indeed, if they don’t, the preponderance of non-democratic practices will likely spill over and threaten the survival of democracy in the political sphere as well.

One can think of democracy as being a mean between two extremes: totalitarianism and anarchy. In a totalitarian social structure there is little or no participation in decision making. In an anarchistic structure everybody is making decisions, but the processes of negotiation and orderly decision making are lacking, so the structure falls into chaos. In a democratic social structure one finds orderly and participatory patterns of decision making and planning that reflect and embody the previously designated subvalues of democracy.

In the quest for control, many people who are strong defenders of political democracy exhibit totalitarian tendencies in the institutions and bureaucracies they lead. On the level of institutional life, perhaps the most salient analysis of the totalitarian structure is to be found in Erving Goffman’s concept of the total institution (see his book, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, 1961). The democratic alternative might best be described as a participatory pattern of administration. In a participatory system all the people who live in a particular social space participate in creating the norms and goals that structure the situation. In the “Humanizing Institutions” section these themes will be explored as they pertain both to the institutions of society that have mandates to care for vulnerable or deviant groups, and to the regular institutions of education, government and business.

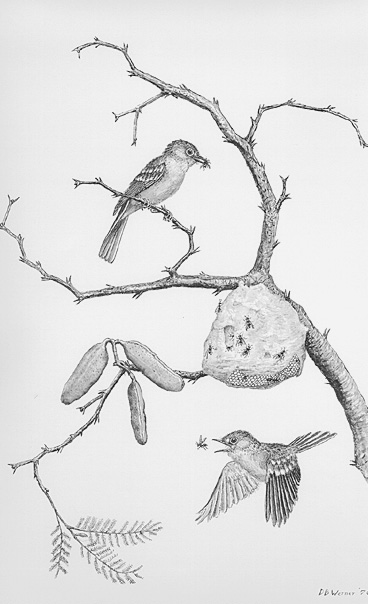

Bird Prints of the Sierra Madre Charcoal Ink Paintings

These 11" by 17" prints of paintings by David Werner portray four characteristic birds of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental. They are available to you for a small contribution.

While each painting is a work of art, it is also a detailed study of the bird species, together with a botanically accurate depiction of typical plant species and native insects.

David Werner studied Sumie ink painting under a Zen Master in Kyoto, Japan, in 1962. His black and white bird portraits reveal a blend between Eastern emphasis on essence and space, and Western emphasis on detail.

|

|

|

Please send me the following prints of David Werner’s BIRDS OF THE SIERRA MADRE with information on the bird and plants in their habitat.

- ___ Magpie Jay (Urraca) Calocitta formosa

- ___ Kiskadee Flycatcher (Chatillo) Pitangus sulphuratus

- ___ Empidona Flycatcher (Enjambrero) Empidonax sp.

- ___ Brown-Throated Wren (Saltapared) Troglodytes brunneicollis

- ___ Complete set of four

|

|

|

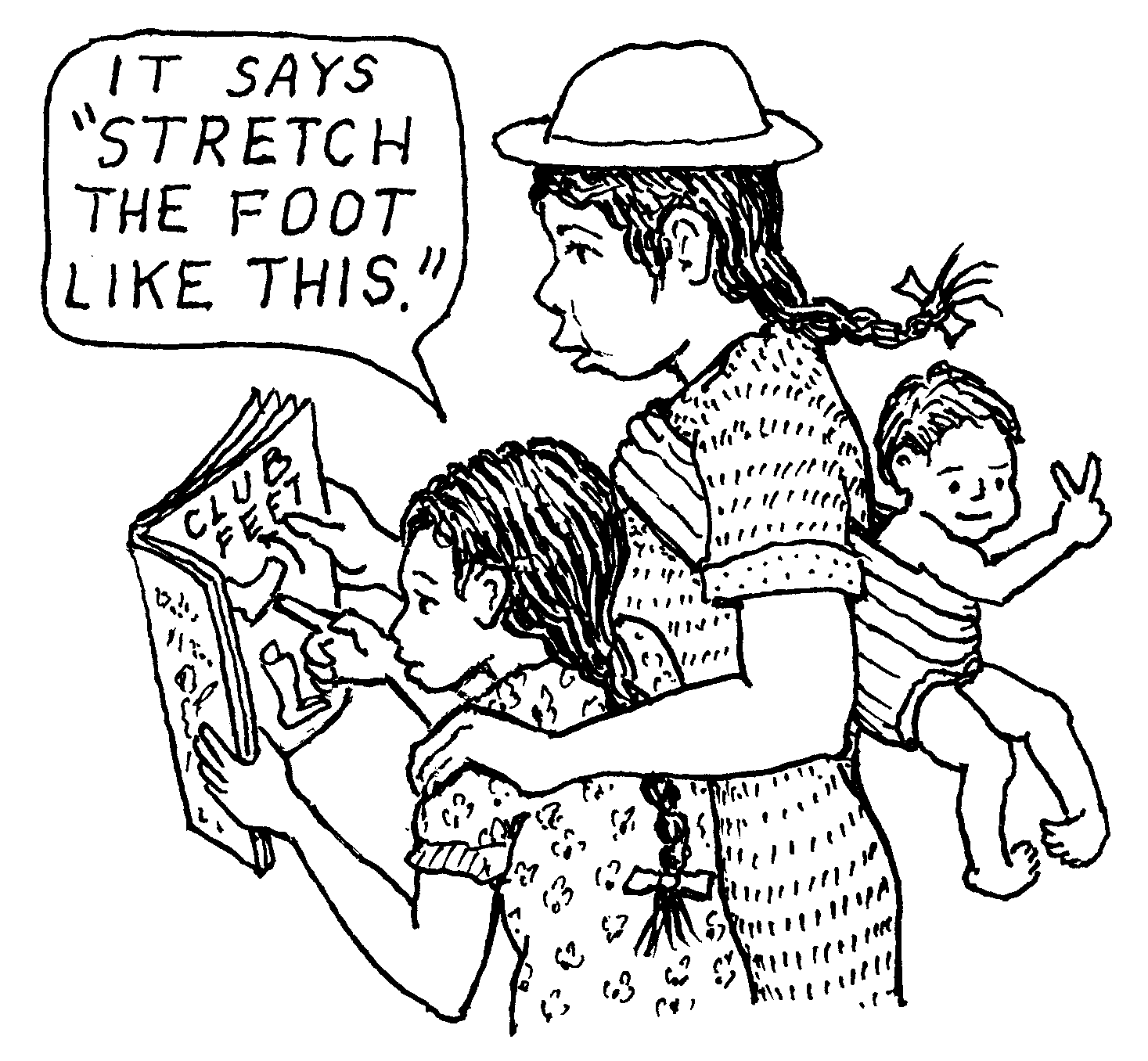

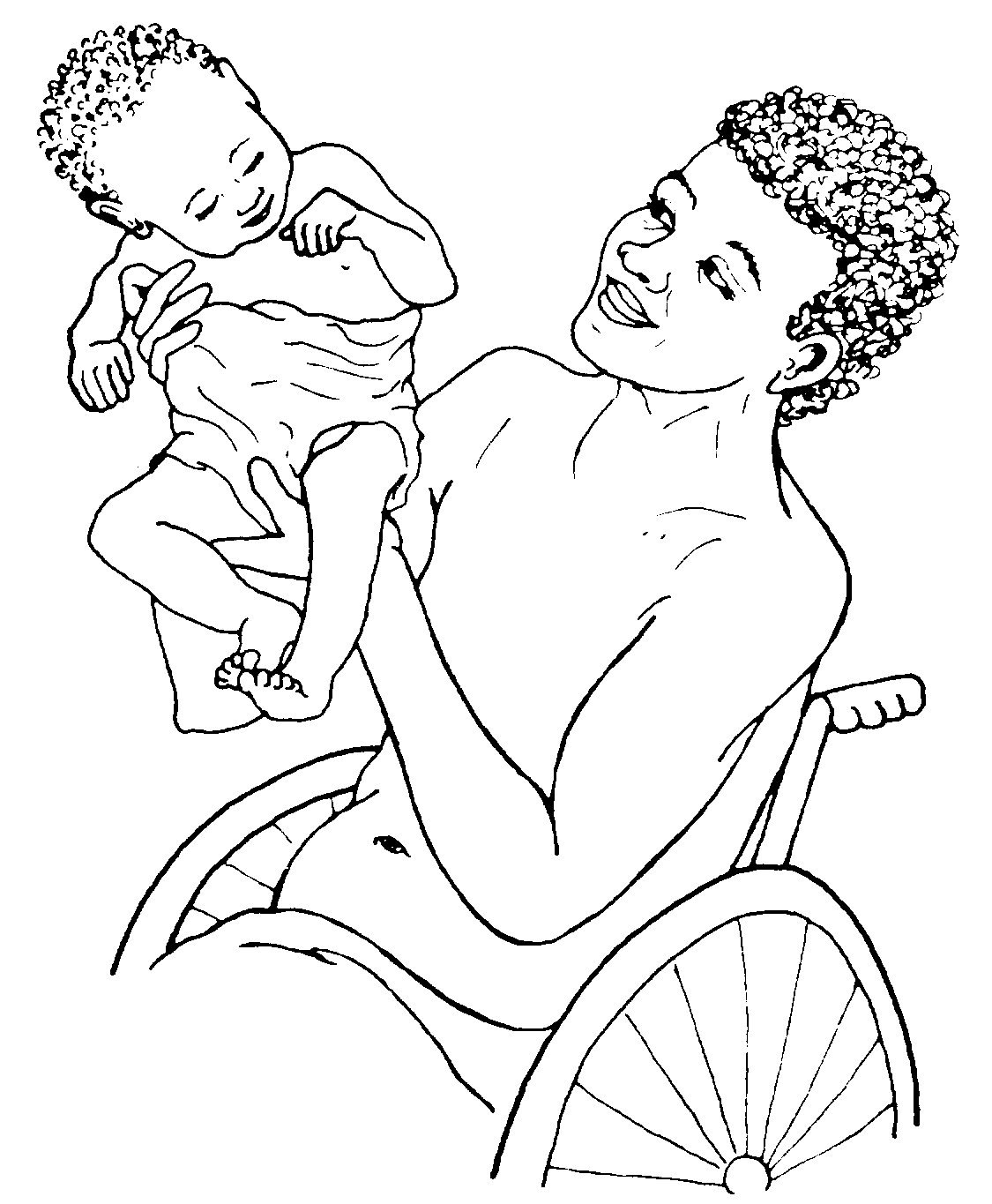

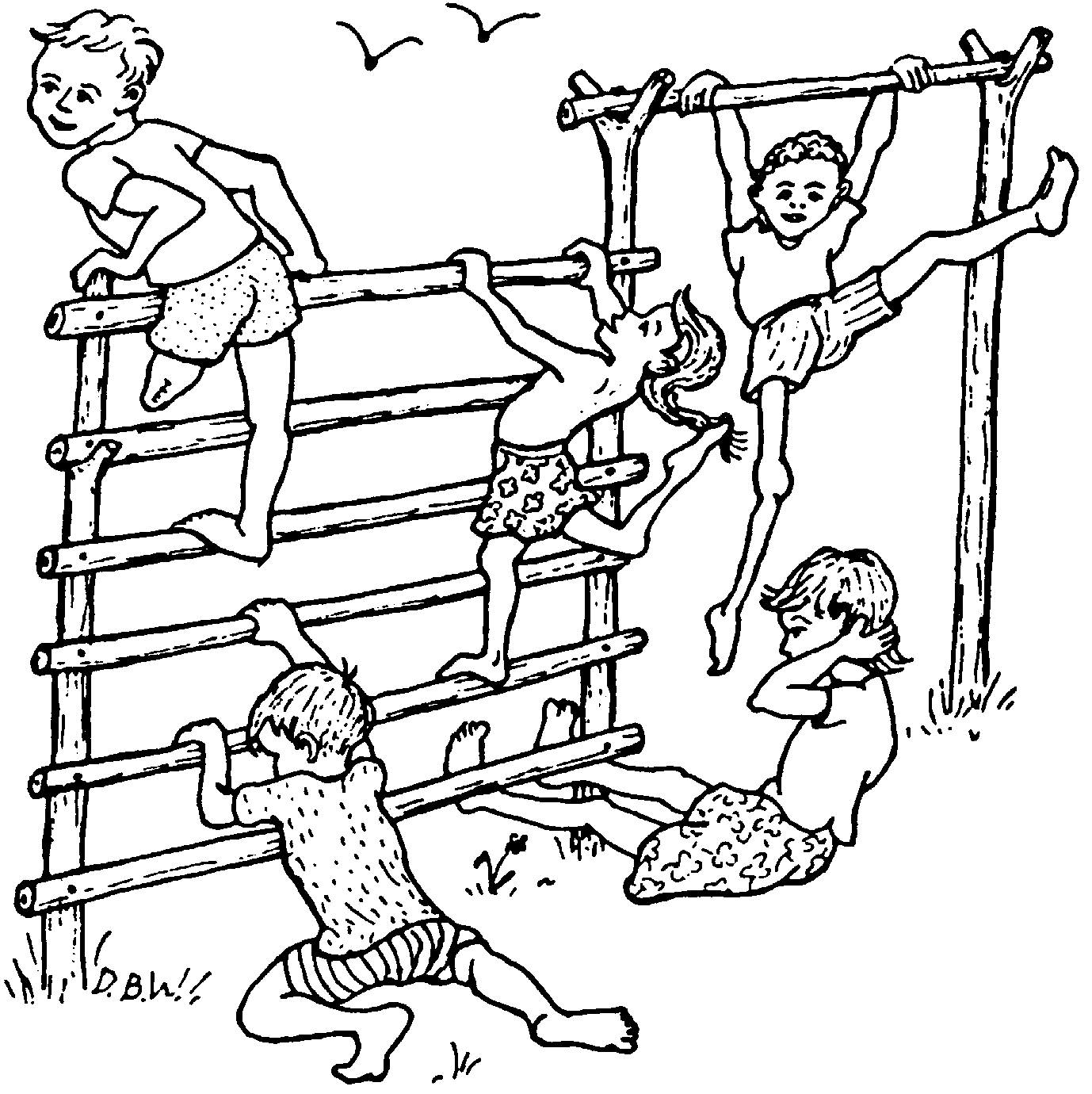

Sets of Greeting Cards Showing Disabled People at Work and Play Hand colored by Village Children

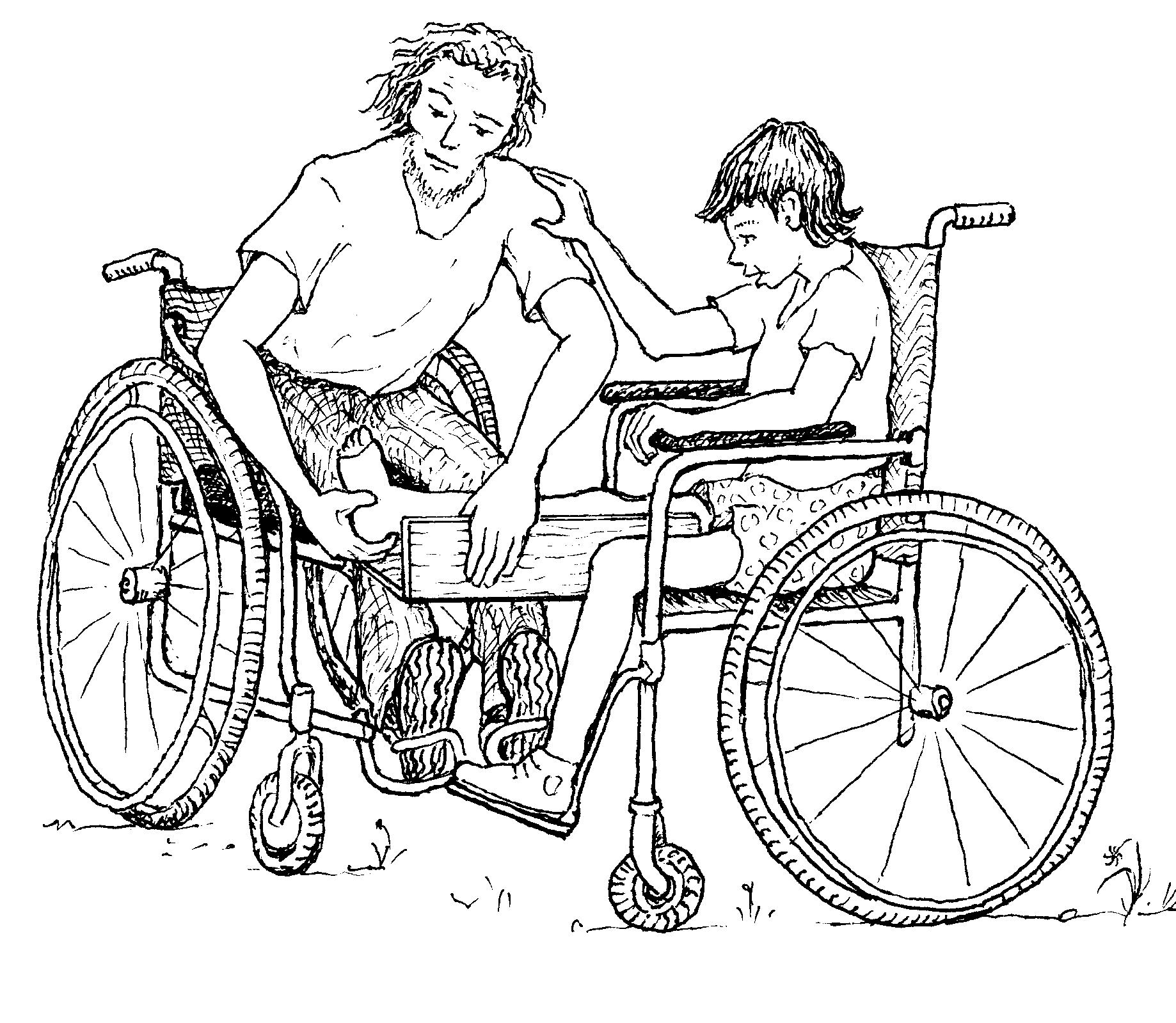

Drawings from David Werner’s books Nothing About Us Without Us and Disabled Village Children have been reproduced, then hand colored by disabled and non-disabled village children. The cards show children and youth playing and actively participating in daily activities at PROJIMO (the Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico).

These colorful cards are especially appropriate for organizations of disabled persons or by anyone who wants society to look at the strengths of disabled folks, not their weaknesses. Proceeds go to the young artists and to PROJIMO.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Update on PROJIMO

Exciting new developments have taken place in both the PROJIMO programs in the past few months, with even more promising prospects for the future.

PROJIMO in Spanish stands for Programa de Rehabilitación Organizado por Jovenes Incapacitados de México Occidental, or “Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico.” PROJIMO at present consists of two largely independent programs, based in two villages located an hour or so north of the costal city of Mazatlan, on the mainland opposite the tip of Baja California.

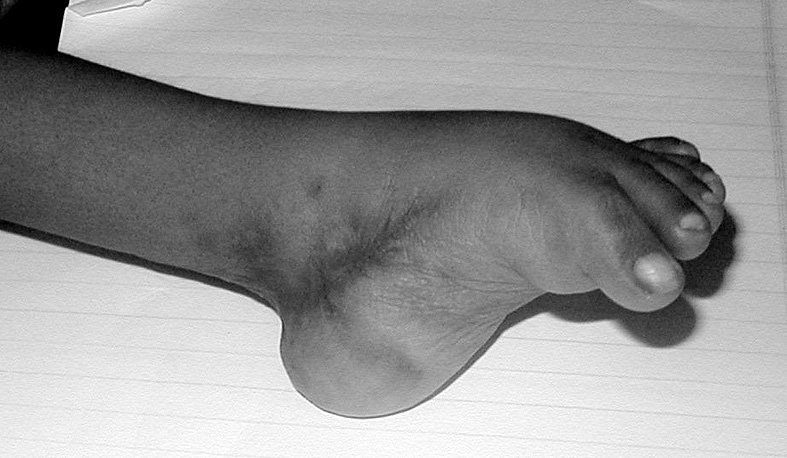

PROJIMO Rehabilitation Program in Coyotitan, Sinaloa provides a wide range of services for disabled children and adults in surrounding villages. Activities range from family counseling to “early stimulation” and skills training. Low cost aids made at PROJIMO include orthopedic appliances, prosthetics, and wheelchairs. PROJIMO’s goal is to help disabled persons, families, and communities became as self-reliant as possible in an inclusive, caring way. Services by disabled persons provide an inspiring role model for disabled young people and their families.

PROJIMO Skills Training and Work Program focuses on the construction of individually designed wheelchairs for disabled children. Because coordinators and workers are mostly wheelchair users themselves, they make sure each chair meets the specific needs of each child. The team is self-sufficient in that it earns its living through the sale of the chairs. Yet no child is ever turned down. For families too poor to pay, Stichting Liliane Fonds, with the municipal government and other donors, covers the costs.

Sharing of ideas, methods, principles of empowerment. The PROJIMO programs are among the few Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) initiatives that are organized and run by disabled villagers themselves. Thus PROJIMO provides an example and challenge to other CBR programs, to achieve strong leadership by disabled persons. The PROJIMO experience has shared and multiplied in several ways:

-

Increasing numbers of volunteers from different countries, especially rehabilitation professionals, are visiting PROJIMO—for days, weeks, or even months. The visiting experts help the workers at PROJIMO upgrade their skills. They also learn from the PROJIMO approach. This November saw visitors came from Holland, England, Greece, Canada, US, and Nicaragua. Many go on to work in CBR programs in Africa, Asia, or Latin America. Ideas gleaned from PROJIMO help them in the design and approach of programs elsewhere.

-

More and more foreign students come to study in the Intensive Conversational Spanish Training Program taught by quadriplegic youth at PROJIMO. By volunteering, the students gain a whole new perspective about the ability of disabled people to take charge of their own lives and programs.

-

Networking with other community programs has increased this year, thanks to an interchange organized around the visit of Hortensia Sierra from Stichting Liliane Fonds (SLF) in Holland, and a new network of CBR programs sponsored by the VAMOS Foundation in Mexico City.

-

A new video presentation is now being finalized by a Dutch team, to share the PROJIMO experience with a wider audience. (The excellent video on PROJIMO, “Our Own Road,” which won a Freddy Award in Documentaries, continues to be aired on public television in the USA and elsewhere.

-

Both PROJIMOs have received increased approval and support from the government, at municipal, state, and national levels. After PROJIMO Duranguito won a national prize for innovative community development, SAGARPA (a state-run rural improvement program) contributed generously toward building the new wheelchair shop and carpentry shop in Duranguito which is almost completed. Another state program is currently helping to upgrade the facilities in Coyotitan. Seed money for these projects was also provided by Stichting Liliane Fonds. The goal is to expand the facilities to accommodate growing numbers of trainees from other programs, in Mexico and beyond.

-

Both David Werner and the disabled PROJIMO leaders have also been invited more and more often to different countries to share their experiences. This year David has helped facilitate CBR training in Mexico, the US, Colombia, Bolivia, Honduras, Guatemala, and Turkey.

-

New prospects are developing for skilled prosthetists and orthopedic surgeons to visit PROJIMO, to help upgrade the teams skills and if possible to work with local surgeons in a shared learning process.

|

|

|

Help PROJIMO Teach Others to Help Others—Make a Year-End Donation!

The PROJIMO team is now entering the “multiplying stage” of sharing their methods and skills far and wide. One way they do this is to invite disabled persons from other programs to apprentice in their workshops. But to do this effectively, they need more equipment, workspace, guest facilities, and funds.

Your donation—in supplies, volunteer help, or $$$—will be greatly appreciated. To make a donation, see the enclosed order form, or contact us for specifics.

End Matter

Please Note! If you prefer to receive future newsletters online, please e-mail us at: newsletter@healthwrights.org

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing |

| Efraín Zamora — Design and Layout |

| Shefali Gupta — Technical Assistance |

| Trude Bock — Proofreading |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |

| Jay Edson — Writing, page 9 |

They no longer use bullets and ropes. They use the World Bank and the IMF.

— Jesse Jackson