Twenty years ago David Werner visited Cuba as part of the California-Cuba Health Brigade. Afterwards he wrote a paper: “Health care in Cuba today: a model system or a means of social control—or both?” For this paper, in which he tried to analyze strengths and weaknesses of the Cuban system, he was jumped on by both Cuba-philes and Cuba-phobes. Now, after revisiting Cuba in May 2004 to evaluate a pilot Community Based Rehabilitation project, he provides an update. He laments the hardships caused by the US embargo, yet reflects on how Cuba has risen to the crisis through innovative steps toward equitable and ecologically sustainable development. In our next newsletter we will provide an in-depth discussion of the CBR program David visited. “Cuba” is now a topic in our restructured Politics of Health website (www.politicsofhealth.org), which we review in an insert to this Newsletter. Lastly, we give a brief Update on PROJIMO, in Mexico.

Cuba’s Creative Response to Hard Times

The Small Against the Mighty

Who knows why? Perhaps it can be traced to the never-ending story of David and Goliath? The small against the mighty? But I seem to have a knack for landing in small struggling countries on the eve of massive protests against abuse of power.

Last Fall it was Bolivia (see NL #50 on www.healthwrights.org). I was headed for La Paz but ended up in la guerra. I arrived in that impoverished country for a national seminar (which was abruptly canceled) the day before the “October Surprise of 2003” when thousands of indigenous poor folks rose up and overthrew President Gonzales. They were sick and tired (quite literally) of their “democratically elected leaders” putting the interests of transnational wealth and power before the basic needs of the common people. They took democracy (people’s rule) into their own hands —not in the voting booths which always favor the fat-cats—but on the streets. Enough was enough!

This Spring it was Cuba. I had been invited to facilitate an “external evaluation” of a Rehabilitation Program in the Province of Granma. But I happened to land in Havana on May 12, the day before a huge protest march. It was even more massive (though far more peaceful) than that in La Paz last October. 1.2 million people took to the streets with banners, posters and megaphones. As in Bolivia, they were protesting the abuse of the weak by the powerful. But in Havana people were not rising up against their own president. They were denouncing the president of the United States and his newest threats against Cuba. They demanded respect for international law. Even the children gave speeches.

Had I arrived one day later, I could not have caught my flight to Granma. The streets in Havana were blocked and everything was closed down.

The overarching “Goliath” against whom both the people of Bolivia and Cuba took a stand is, of course, the same. It is the dominant economic system—led by the U.S.— that puts the fortune of the few above the well-being of people and the environment.

There are those who say that the massive “Marcha” in Havana—barely mentioned in the US mass media—was imposed by Castro: that workers, students, hospital staff, police, soldiers, and all public servants were obligated to take part in the event.

But in talking with the people in Cuba—even those critical of their nation’s top-down power structure—I sensed their anger at the US government is real.

It is not just based on brainwashing, although “manufacturing of consent” certainly exists in Cuba, as it does in the US. The Cuban people have suffered dire long-term hardships because of US hostility against their nation, especially the embargo. The Cuban government has controlled access to essential goods in order that everyone’s basic needs can be met, given the desperate economic limitations. People have no question that these hardships have been aggravated by the US attempt to bring the island nation to its knees. The shortages are painful. Food is rationed. Fuel is rationed. Wages are witheringly low. Purchases of non-essential goods are curtailed, or priced so high that only those with “divisas” (dollars sent by relatives in Florida) can afford them. As a taxi driver in Havana told me sullenly, “Our entire lives are regulated.”

Nobody in Cuba enjoys this “Big Brother” overseeing of their economic lives (and fewer still will discuss it, at least with an outsider). A thoughtful Cuban school teacher told me that most Cubans, given the opportunity, would migrate to another country. Some would choose the United States. Yet many, he said, would not: they realize that for poor people, life in the US can be harder than in Cuba. Many more people in the United States—especially immigrants and minorities—end up jobless, chronically hungry, or in prison.

US critics of the Castro regime say people of Cuba are oppressed by undemocratic tyranny. That if the US invaded Cuba (as Florida Governor Jeb Bush has urged his brother George to do), to “free” its people and bestow democracy, the Cuban people would embrace the US “freedom fighters” with open arms (just as the White house predicted Iraqis would do when the US invaded Iraq). But Cuba is not Iraq and Fidel is very different from Saddam. Saddam for years was a favorite dictator and pawn of the US government. He committed crimes against humanity and violations of international law with full US backing. (In fairness, Saddam also did more to raise the standard of living of the poor and to defend women’s rights against fundamentalist oppression, than have many Middle Eastern dictators backed by the US).

Castro, to the contrary, has consistently sided with the poor and downtrodden. He has been on the shit-list of US big-business ever since he and his comrades overthrew the Cuban dictator, Batista (who was as much in the pocket of wealthy US interests as was Saddam in his heyday). Despite the economic crisis caused by the embargo—the rationing, the hardships, and the top-down system of social control, which nobody likes—Fidel still has strong popular support. Even many who would flee the country to escape the pervasive hard ships caused by the embargo praise what the “Cuban Revolution” has done for the people. Few say Fidel is perfect. But most people insist that the poor majority in Cuba is much better off than it was under the strong-hand of Batista. In those cruel days 2/3 of the farmland and most industries were owned by wealthy Americans. Impoverished children died like flies from malnutrition and preventable diseases. By contrast, today every child has free schooling, free health care, and (almost) enough to eat.

People in Cuba who spoke to me frankly estimate that Castro still has devoted backing of about 70% of the population—strongest among the poor. They deeply appreciate the incredible network of social services and public assistance that has given Cuba health statistics equal to those of much wealthier nations.

With Fidel’s strong popular support—which he depends on to sustain his leadership—it somehow rings hollow when his critics make such a big issue of his not having been democratically elected. After all, George W Bush got into power with the ballots of less than 25% of eligible voters (half didn’t vote at all)—plus rigging of voter registration, faulty ballot boxes, and intimidation of minorities.

Before the last US presidential elections, Fidel—with good reason—offered to send election observers from Cuba to the US, to make sure the voting process was honest. Had this been allowed we might have a different president and a different world today.

Cuba’s Amazing Health and Welfare Achievements

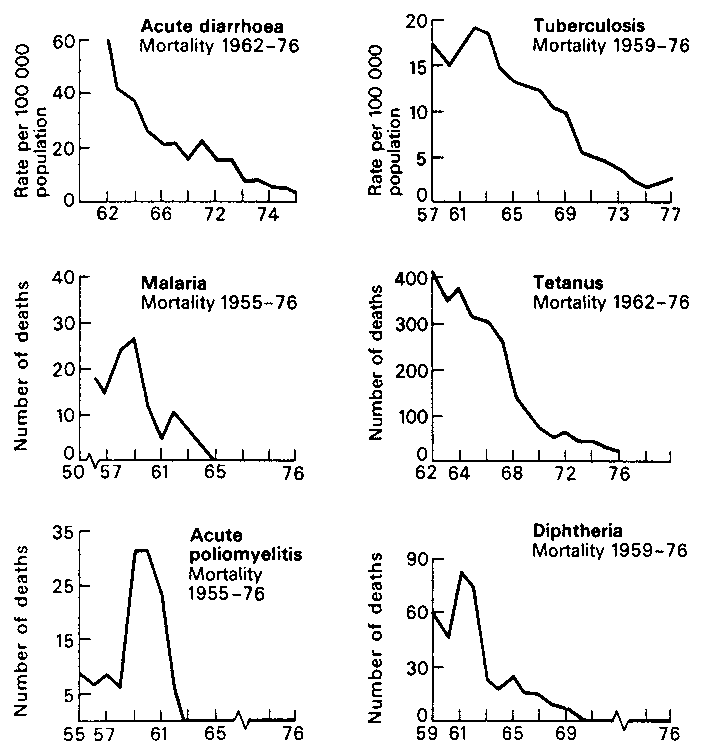

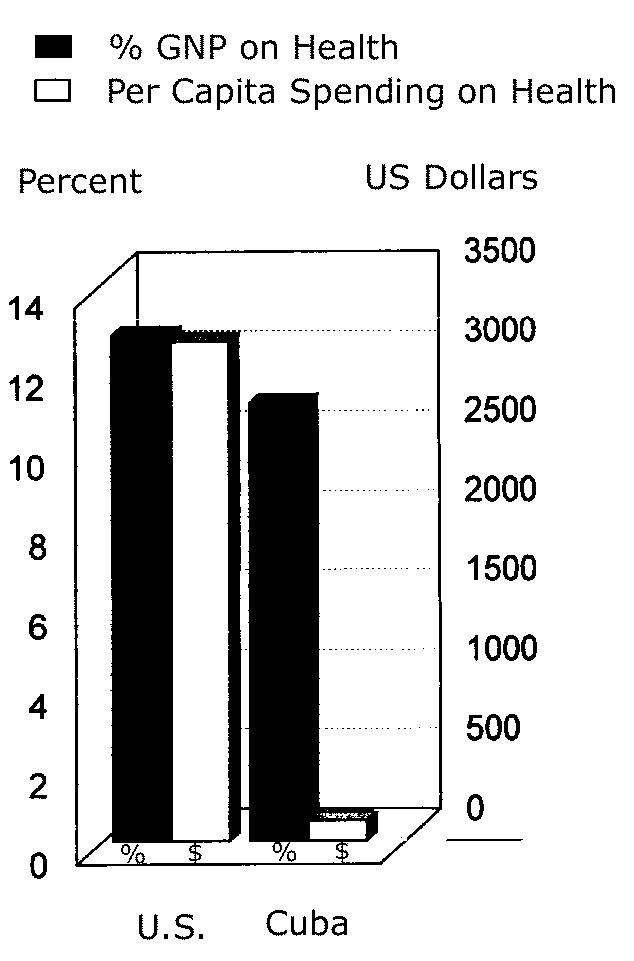

With 1/20 of the per capita income of the United States, Cuba has achieved levels of health, and health care coverage, equivalent to and in some cases better than in the US. In 2003 the under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) for Cuba was 9 per 1000 live births, compared to 8/1000 in the USA. Vaccination coverage for children and pregnant women was better in Cuba (almost 100%) than the US. Maternal mortality is lower in Cuba.

Likewise, the adult literacy rate in Cuba is among the world’s highest. The country places top priority on health and education, making sure that virtually every child—even in the most remote villages of the Sierra Maestra— has access to both. Cuba has won awards from UNICEF for its exemplary achievements in health and education. The World Health Organization (WHO) lauds Cuba as the only poor country to approach its Primary Health Care goal of “Health for all by the Year 2000.” More amazing still—despite the end of Soviet assistance with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 90s, followed by the tightening of the US embargo—Cuba has managed to maintain its extraordinary high levels of health.

The Positive Outcomes of Hard Times

Every cloud, they say, has a silver lining.

The stated purpose of US embargo against Cuba, now in its 45th year, is to “Free Cuba” by wreaking havoc on that small island nation’s economy. The strategy is to cause so much suffering among the citizens that, despite their resilient solidarity, they gradually lose hope and turn against their government.

Without question, the embargo has led to dire grievances, including health problems. During the “special period” in the 1990s people’s average calorie intake dropped by a third. Deaths resulted because of the restricted import of certain medicines and life-saving equipment (or spare parts). The scarcity of fuel and even basic supplies such as paper and copy machines created major obstacles to the daily functioning of society.

But while the US embargo has caused substantial hardships, it has not precipitated the same deadly results as did, for example, the decade-long embargo against Iraq after the first Gulf War where, according to UNICEF, disruption of the economic infrastructure, health care, water purification, and food supply caused over 500,000 child deaths.

By contrast, Cuba, despite the increasingly harsh US embargo, has somehow managed to sustain a high level of health and infrastructure of public services that provides a model for both rich and poor countries.

Far from forcing Cuba to its knees, in some ways the embargo has done quite the opposite. The US strongmen underestimated this island nation’s creative perseverance. Rather than bite the dust, the population has explored ways to turn crisis into an opportunity to do things more equitably and sustainably.

The results are, indeed, ironic. Spurred by the devastating hardships of the embargo, Cuba has become a model for the world, not only for universally meeting people’s health, educational, and other basic needs at low cost, but also for innovative sustainable ecological development.

Let’s look briefly at the diverse ways that the US embargo triggered Cuba’s impressive improvements in both human and environmental health: Consider oil. After the demise of the Soviet Union the US drastically blockaded Cuba’s access to fossil fuels. For several months the transportation system in Havana came to a disruptive halt. Buses, taxis and trucks stood idle. Children missed school. People were late to work. Fire engines were detained.

But within a year, Cuba imported a million bicycles from China. The city began to move again: more slowly but more cleanly. And unexpectedly, in vital ways, people’s health began to improve. The heavy smog layer that had carpeted the city diminished and the high rate of asthma declined. With the increased exercise, the number of obese people (notably fewer than in the US to begin with) decreased. This—combined with decreased consumption of red meat and increased intake of soybean (also a response to the embargo)—has reduced the incidence of heart disease and stroke.

Traffic accidents have also declined.

The import of a million bicycles was just they first step in Cuba’s handling of fuel shortage. To replace motor vehicles, Cuba launched a campaign of breeding horses, mules, and oxen. To my amazement, in the city of Bayamo, in the eastern part of the island where I was evaluating a program, for every gasoline-run taxi there were at least 50 “bici-taxis” (bicycle rickshaws) and 50 “caballotaxis” (horse drawn carriages). Farther back in the Sierra Maestra a major form of food transport is by mule train.

Likewise in agriculture—now that giant plantations have been divided—many of the small lots are plowed by former serfs using mules instead of tractors. As a result, the yield has increased.

The fossil fuel shortage has also compelled Cuba to experiment with other forms of alternative energy, including solar, wind and hydro. As a part of the nation’s Education for All program, even the most isolated mountain villages have a community “Television Hall” where children and adults can view videos on everything from traditional healing to cultural events, bee-keeping and nutritional advice. To power these big television sets, many of the Television Halls and village school houses are equipped with solar panels. And throughout the Sierra Maestra “mini-hydroelectric stations” are powered by tiny dams collectively constructed along mountain streams.

Cuba has an ambitious long plan of gradually converting energy production to renewable resources, thus avoiding dependence on imported oil. In this way Cuba, along with Greenland which has similar goals for renewable energy, is providing an example for a healthier, more sustainable, more peaceful world.

Consider Food and Water

Adequate nutrition is the sine qua non of health. Along with universal health care and education, a goal of the Cuban Revolution is that every person get enough to eat. In this regard, its achievements are astounding. On my travels this May to the poorest and most remote huts in the mountains, I never saw a seriously malnourished child (except for one girl who was profoundly disabled). To the contrary, the consistently healthy, eager, happy look of the children warmed my heart.

Nevertheless, keeping its children adequately fed in the face of the embargo has been an uphill struggle. Despite a serious drop in average calorie intake during the “special period” of the ’90s, Cuba—unlike Iraq—has managed to make sure the basic requirements of virtually every child are met.

To sustain subsistence levels of nutrition despite import restrictions, Cuba has had to become much more self sufficient in food production. With 11 million mouths to feed on the small island, radical changes in land use and agricultural crops were needed.

Since colonial times, Cuba’s primary crop was sugarcane. Export of sugar kept the economy afloat. But today Cuba imports most of its sugar from Brazil. This reversal is due in part to the fall in the world market price of sugar, and in part to the US blockade. But the biggest reason was for self-reliance in food production—by converting cane fields to farms producing food crops for local consumption.

Advocates of ecologically sound development have been delighted that the Ministry of Agriculture—driven in part by the constraints of the embargo—has introduced a number of innovative measures for the sustainable increase of yield.

There has been a major shift toward “organic farming,” not driven by new-age purism but by the pragmatic boot of sheer necessity. A decision was made to substantially cut back on use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers—for two reasons: 1) import barriers made their cost prohibitive, and 2) research in Cuba and worldwide show that natural fertilizers and biological pest-control provide higher, more sustainable, more nutritious yields at lower cost than do chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Therefore a campaign was launched whereby extension workers taught farmers “alternative” methods—such as:

-

mixed cropping and use of insectrepelling plants (with pyrethrums),

-

terracing with soil-retaining fodderproducing hedgerows to prevent loss of top-soil by runoff in heavy rains,

-

drip irrigation to conserve water as well as soil nutrients,

-

use of legumes to return nitrogen to the soil, and

-

mulching of waste vegetation, along with cultivation of earthworms for production of natural fertilizers.

The return to use mules and oxen for plowing, in addition to reducing dependency on scarce, costly imported fossil fuels, also adds another source of fertilizer: manure.

In the cities a similar agro-revolution has taken place. School children, women’s organization, and local Committees for Defense of the Revolutions have been mobilized to convert patios, vacant lots, and alleys into home and community vegetable plots. Today 93% of the fruit and vegetables consumed in Havana are produced within the boundaries of the city, thus helping to resolve the nation’s food crisis in a local and sustainable way.

In some areas water is also becoming a problem, because of global climate change and local deforestation. To reverse the trend toward deforestation as well as reduce soil erosion and excessive groups and community organizations have been mobilized in high spirited tree-planting campaigns.

In short, to meet the basic food needs of all people in a sustainable way, Cuba has embarked upon a national plan that is ecologically balanced, sustainable, and increasingly self-reliant at the national and local levels. As such, Cuba provides an example for the rest of the world of practical measures for reducing dependency on fossil fuels, for reversing the green house effect, and letting humanity learn to “live and let live” in balance with the natural world.

Unfortunately, it is this “good role model” of sustainable, equitable development in the pursuit of “Health for All” that makes Cuba so unbearable to the potentates of the deregulated market system, with their ideology of “economic growth regardless of the human and environmental costs.”

Consider Medical Services and Biotechnology

Another area where the embargo has provoked unanticipated breakthroughs is in the field of medical science and research. Indisputably, the refusal by the US to make available certain urgently needed pharmaceuticals, medical supplies, and spare parts for diagnostic and therapeutic devices has caused health-damaging and at times fatal setbacks for Cuba. However, the same shortages have driven Cuba to greater innovation and self-reliance. For example, the country now produces internally all the 13 standard vaccines it routinely uses to immunize all the country’s children. Plus it has developed and given to the world other important new vaccines, including ones against hepatitis B and meningitis strain B.

Cuba today is internationally esteemed for its research and development of essential new drugs. Indeed, export of these critically needed products has become a valuable source of income for Cuba, and has led other countries to resist supporting the US embargo. Among the most sought-after drugs is “Interferon Alfa” and various innovative drugs for preventing rejection of organ transplants.

Also adding to its world renown, Cuba has also developed a unique capacity for advanced surgical procedures, including a wide range of sophisticated organ transplants: heart, heart+lung, kidney, pancreas, liver, cornea, and bone marrow. Availability of organs in Cuba is greater than in other countries because the people take pride in contributing. More than 90% of the population has voluntarily signed up for organ donation. Each person carries an identification card providing details on his or her histocompatibility. A network of rapid ground transport optimizes logistics of supply.

The quality and success of transplants is now so well recognized that many countries refer patients to Cuba. Like other medical services, all transplants are completely free to Cuban citizens. Persons from other countries who have health insurance are asked to pay. But uninsured persons from Third World countries are provided free services.

In its belief that health care is a human right, Cuba provides health services to people in many poor countries. Sometimes it brings them to Cuba for specialized procedures, but more often it sends Cuban doctors—including specialists—to serve in countries where there is a dire shortage. Over the years Cuba has sent more than 10,000 doctors for service abroad, with as many as 1,500 at any one time. This magnanimity does not cause a doctor shortage in Cuba because the country trains so many. Cuba has one doctor for every 225 citizens, as compared to the US, that has one doctor for 450.

Another way Cuba reaches out to disadvantaged countries is by providing hundreds of scholarships for persons in poor countries to study medicine in Cuba. Ironically, Fidel has recently offered complete scholarships to medical schools in Cuba to 500 US citizens. There are those who say Fidel does this to thumb his nose at the US. But he points out, quite accurately, that among US doctors, minority groups are seriously under-represented; over 40 million US citizens—mostly poor people of color—have no health insurance. The Cuban scholarships are offered primarily to Blacks and Latinos, specifically to those who agree to use their medical training to serve the needy in undeserved communities when they return to the US.

So far about 60 Americans have enrolled in the Cuban medical schools. Of these only a quarter have stuck it out. Even Americans from humble backgrounds tend to find the Cuban conditions very Spartan. The US students are treated just like the Cuban ones. All their basic needs are paid for, including room (in a dormitory) and board (adequate, but no frills). While they study they are paid the standard minimum wage of US$4.00 per month. That allows for very few luxuries. In short, the Americans have to live with the same limited resources as do the Cuban people under the constraints of the embargo. The one big difference is that the Americans can leave. So far three out of four have done so.

Despite its huge commitment to health, Cuba—with 1/20 the per capita income of the US—spends a lower percentage of its national budget on health care than does the US, and a small fraction of what the US spends per person. Yet the two countries’ health statistics are similar. How is this possible? One reason is that in Cuba doctors and medical researchers don’t get paid much more than those who grow their food. In Cuba farmworkers and laborers earn about US$5.00 per month. The average doctor earns $15 a month. Everyone’s wages are so low because their basic needs are provided for. This evens things out. You can afford a lot of doctors at $15 per month. In the US, where many doctors earn over $12,000 per month, health care is placed out of reach of the working poor, 44 million of whom have no health insurance.

In the Golden Age of Greece, Plato suggested that in a just society the highest wage should be no more than 5 times the lowest wage. Cuba more or less conforms to this principle—as compared to the US where top CEOs are paid over 300 times as much as their employees. Such inequality imposes serious costs on the health of individuals and of society as a whole.

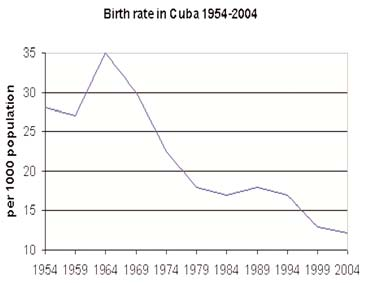

Consider Population

Unlike most of Latin America, Cuba has never pushed population control or “family planning” (though a range of methods are freely available). Yet the high birth rate that occurred under the inequitable Batista government dropped steadily after the 1959 Revolution. Today Cuba has one of the lowest birth rates in the Americas. Why? Because when a society collectively makes sure that all people’s basic needs (for food, shelter, health care, care in old age, etc.) are met, advantages of having fewer children outweigh those of having more.

As the women’s reproductive rights movement’s declared in the ’70s: “Take care of the people’s problems and the population problem will take care of itself.”

So in terms of stabilizing population growth—which many argue is necessary for ecologically sustainable development—Cuba again provides an important lesson to the world: Population stabilization is more likely to be achieved through promoting better quality of life rather than explicitly trying to reduce population growth.

When will we learn?

Consider Community Health and ‘Power to the People’

The dream—or better said, the vision—of the Cuban Revolution as portrayed in the early writings of Fidel and Che is based on human dignity, inclusion, and equality—that is, equal rights and equal opportunities—for all people. Hence Health for All has been given such central importance, where health is seen, in accordance with WHO, as “complete physical, mental, and social well being.”

But dreams or visions are not achieved overnight, not even in the course of decades. What is more, they are not static; they keep evolving.

In pursuing the dream of equality and equal opportunity for all in Cuba, as elsewhere, certain contradictions have arisen. One contradiction has to do with the centralization of decision making authority. Another related contradiction, evident in the field of health services, has to do with professionalization—and confusing coverage with quality of care.

One key indicator of health—be it of an individual, community or nation—is the vital balance between self-reliance and shared responsibility. That is to say, between independence and interdependence. Between freedom and belonging. Neither the vision nor praxis of this healthy balance can be imposed top down. It can only grow slowly from the bottom up, through an open-ended process of collective discovery and struggle.

Visionary leaders recognize the alliance between revolution and evolution: the perennial need for creative change. Cubans rightly speak of their “Revolucion” not as a finite historical event (i.e. the overthrow of the Batista oligarchy in 1959) but as an ongoing uphill struggle.

Similarly, Thomas Jefferson—main author of the US Constitution—wisely opined that a Revolution to endure needs to be re-fought every 20 years. Mexico, after its internal Revolution for “Land and Liberty” in 1910, tried to perpetuate the revolutionary zeal by forming the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI)—as if the spirit of change can be cast in stone, or tethered like a wild eagle to a flagpole. Rather than encourage change the PRI resisted it. Through heavy-handed abuse of power and rigging of votes when necessary (like Bush) the PRI remained in power for 70 years; the gap between rich and poor widened even more than it has in the United States.

Is it any wonder Fidel scoffs at the institutionalized inequality that the US, in the name of “democracy,” would impose on Cuba?

Cuba does not pretend to be “democratic”: at least not in the All-American way.

It sees the “low intensity democracy” of the planet’s remaining superpower as an unsustainable system that permits unbridled “freedom” to an elite ruling class to further concentrate its wealth and power at enormous human and environmental costs.

Amazingly, despite its enormous economic constraints inflicted by the US embargo, Cuba has managed to keep many of its Revolutionary ideals alive. The fact that it has sustained its extensive coverage of health and public services is a measure of this commitment.

However, even after the Revolution, health care in Cuba as in most countries tended to be very top down. Even the most basic services at the community level were provided by professionals. Rather than enable people in communities to learn more skills and assume greater responsibility for meeting many of their health needs themselves, this community-based approach was resisted.

This I observed on my first visit to Cuba, 25 years ago, with the so-called California/Cuba Health Brigade. Rather than train community health promoters as the frontline health workers, Cuba took pride in making sure that there were enough doctors, even in the most remote areas, to treat every ailment. My own long experience in village health care in Mexico gave me a different perspective. I had come to realize that the first level of health care providers is mothers in their homes. Most mothers already have a wealth of local health-related knowledge and skills passed on to them by their own mothers and grandmothers, and the traditional healers. If a health program can help mothers learn more about the basic health needs of their children (including danger signs when they should seek more skilled help), often they can prevent or treat many of the most common ailments earlier and as well as doctors, and at lower cost.

On my first visit to Cuba 25 years ago, I asked about the management of diarrhea, then the biggest killer of children in most poor countries. Research by UNICEF and others has shown that teaching mothers (and school children) how to give “oral rehydration therapy” (ORT), a simple drink or cereal gruel prepared in the home, can prevent many young children with diarrhea from dying of dehydration. At that time, however, MINSAP (the Cuban Public Health Ministry) did nothing to teach mothers about ORT. When I asked why, I was told they discouraged “home care” because they wanted mothers to seek help from the doctors.

“But what if the doctor is 3 hours away on a hot trail?” I argued. “A baby can dehydrate and die in that time!”

“There is a family doctor in almost every community,” I was told. I also discovered that although diarrhea is common in Cuba, few children die from it. This low mortality rate was explained by the wide availability of professional treatment. A more likely cause, however, is that there are almost no severely malnourished children in Cuba. Undernourished children run a far higher risk of dying from diarrhea. China also has a high incidence but low mortality from diarrhea; and China, too, made a supreme effort to make sure all its children had enough to eat. Yet China, unlike Cuba, embraced traditional forms of healing, including home-based oral rehydration. And rather than place a medical doctor in every village, China placed more importance on the role of “barefoot doctors.” But shoes or no shoes, the protective force of getting enough to eat must not be underestimated.

I had found, 25 years ago in Cuba, that the use of traditional medicine, herbal remedies, folk healers, like the use of community health promoters, was actively discouraged. “Just because people are poor, doesn’t mean they deserve second-class medicine,” I was told. “Every human being deserves the best.”

Nothing I could say would convince the health authorities that there was a place for community-based health care. I tried to argue that local village health promoters and mothers in their homes, if given appropriate training and support, could serve not as a substitute for the professional health system but as an adjunct. But it seemed no one agreed.

I was delighted, therefore, when, on returning to Cuba last May, I witnessed a remarkable turnaround. Whereas in the earlier years of the Revolution, community-based health care and traditional healing were rejected as “second-class,” today there is growing interest in herbal remedies, “alternative medicine,” and in teaching mothers and school children certain aspects of home care. All young doctors, as part of their training in medical school, are now taught “community health promotion” and the importance of using efficacious traditional forms of treatment. The ancient “cure all” of bathing in hot mineral springs (spas) has been reintroduced for treatment of joint pain and certain skin conditions. Sophisticated research is being done on native medicinal plants, in collaboration with traditional healers. Family doctors have posters on their clinic walls depicting different medicinal plants, and give classes to both adults and school children. On the wall of one health post I visited, I was happy to see attractive posters on how to prepare a home-made “oral rehydration” drink to give to a child with diarrhea.

All this indicates that in the field of public health, at least, the Revolution is still alive and active. It continues to evolve and be open to new possibilities, and in the process it is coming closer to its all-embracing vision of inclusion and equality for all.

In the early days of the Revolution, health care was advanced as an equal right for all, but it was delivered by highly trained experts with little participation by the common people and little appreciation of their traditional knowledge and abilities. Services were definitively top-down. Rather than encouraging self-reliance, they created greater dependency on “those who know best.” Today there is more equality, more sharing of both knowledge and responsibilities, more respect of people’s traditional knowledge, for self-determination, and for participatory problem-solving. Thus the vision of the Revolution moves closer to being realized. To learn is to change.

In a remote village in the Sierra Maestra I asked an African-Cuban doctor why he thought public health policy had shifted from a highly professionalized, top-down, dependency-creating model to one than was more participatory and community based. His answer: “The embargo. We had no choice.” He explained that the shortage of medicines, of fuel for distant home visits, and other limiting factors had forced MINSAP to rethink its approach to community service. It started off reluctantly and then became more eager and creative. Finally it realized that what the medical establishment had reviled as a step backward was in fact a step forward. Currently Cuba is not only investigating medicinal plants, but has made some promising discoveries not only for local use but possibly for export.

Here again, we see that the US embargo, rather than undermining the Cuban Revolution, is in some ways bringing it closer to the vision of genuine equity and “poder popular” (power to the people)—an alternative model of health and development that the corporate class in the US has good reason to dread.

But What About AIDS in Cuba?

AIDS control in Cuba has long been controversial. Cuba has had exemplary success in limiting the spread of HIV. But AIDS and human rights activists, in the past, strongly criticized Cuba for its mandatory segregation of HIV-positive persons into “sanitaria,” comparing them to leper colonies. Cuban officials argued that although quarantine was necessary for the common good, persons with HIV were treated better than in most countries. Indeed, because the first cases of AIDS in Cuba were soldiers and doctors returning from wars of liberation in other poor countries, they were seen as heroes. Though required to reside in special HIV sanitaria, they were treated with respect and provided better living conditions than the rest of society. Even in the early days of the HIV program, most HIV+ persons were allowed to visit their families, go to work, and participate in social activities.

In recent years, however, policy has shifted toward integrating HIV-positive persons into the general community, where they are closely monitored. They receive regular visits by doctors, social workers, and other support personnel. Those dwelling in the HIV sanitaria were given the choice to stay or to leave. Half left, but half chose to stay because the conditions, food, and support services were so favorable.

Not only has the incidence of HIV in Cuba remained remarkably low, but the survival rate is unusually high. Everyone who is HIV-positive receives optimal multi-antiviral treatment plus good nutrition, vitamin supplements, and early diagnosis and treatment of opportune infections. Research is underway using Interferon Alfa and other drugs to build up resistance to secondary infections.

WHO has praised Cuba for its outstanding success in limiting the spread of HIV. Cuba has a comprehensive program of education and prevention. This includes mandatory testing of all medical personnel, pregnant women, persons with other STDs and their partners, prisoners, merchant marines, and citizens having traveled abroad. Voluntary testing is encouraged of the general population, especially those with multiple partners. In all, 2 million of Cuba’s 11 million citizens have been tested.

In two ways Cuba’s AIDS control program differs strikingly from most others. First, condoms are not widely available, although their use is encouraged in AIDS education. The government solicits donations of condoms from donor countries, but does not produce its own, which is surprising in view of Cuba’s high technology in other areas. Limited availability of condoms is explained by “cultural reluctance” to use them.

The second way Cuba’s response to AIDS differs is the role of prostitutes. Interestingly, in Cuba the slang for sexworker is jinetera (female) or jinetero (male). Jinete in Spanish means eques- trian, or jockey: the rider of a horse. This implies the sex worker is the one in control, who sets the terms. Unlike in most countries, in Cuba most jineteras/os apply their trade only occasionally or part time. Many are students, nurses, or have other jobs. While some engage in sex for payment between men and women, the affluent and the destitute, adults and youth, the self-righteous and the deviant, the blessed and the damned—may be the only definitive solution to halting the spread of AIDS.

What We could Learn from Cuba

Rather than trying to isolate Cuba, the United States and the world should be learning from its good examples: Health Care for All, a humane, egalitarian approach to AIDS prevention, weaning from dependency on oil, stabilization of population growth, and sustainable environmental development.

This is not, of course, to say that everything in Cuba is perfect.

Cuba has some huge problems, including sometimes heavy-handed centralized control. In large part because of the US embargo and attempts by the CIA to infiltrate the country and undermine the government, freedom of the press and of political dissent are limited. Because of the economic crisis, living conditions are frugal and equitably regulated. Luxuries and availability of non-essential goods are restricted (except for tourists, which contradicts the principal of equity but is deemed necessary to bring in needed dollars). Another serious contradiction is that half the people in Cuba receive economic assistance from relatives in the US, while the other half do not. This is leading to a two-tiered society that mocks Cuba’s egalitarian goals.

For all these limitations, however, in terms of meeting all people’s basic needs there is more equality and social justice in Cuba than in most countries, rich or poor, including many that claim to be democratic. Much could be learned from Cuba to make the world healthier, fairer, and more peaceful, and life on this planet more sustainable.

While the US embargo has made life in Cuba much more difficult, and has aggravated the severity of top-down social control, paradoxically the challenges arising from the embargo have driven Cuba to achieve an alternative model of universal health care and sustainable development.

The embargo is a two-edged sword. The majority of US Congress, in both parties, want to end the embargo. But the Bush Administration, to win the vote of the wealthy anti-Castro Cubans in Miami, has pushed through new, even harsher measures.

Ironically, to end the embargo and launch “free trade” between the US and Cuba may pose the biggest threat to the survival of Cuba’s revolutionary model of equitable and sustainable development. The number of tourists—now over 2 million—that visit the island annually is increasing. Transnational corporations are eager to invade the island with billions of dollars worth of trade. Big money corrupts. Paradoxically, repeal of the US embargo may bring about the end of the Revolution much more effectively—and in the long run, more perniciously—than keeping the embargo in place.

Yet Cuba’s leaders insist that, after the embargo is lifted, the revolutionary approach to equitable and sustainable development that has evolved during the last half decade will not be swept away by the tidal wave of global free trade. But who knows? Cuba’s biggest challenge—like that for the rest of the planet—may be yet to come.

Help Cuba Help its Disabled People Help Themselves

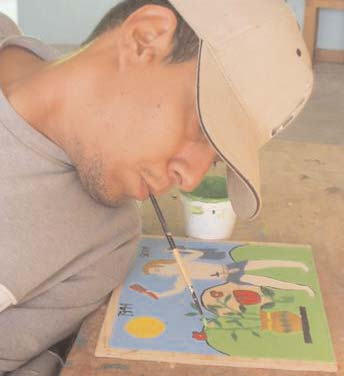

The field workers, or Activistas, volunteering in Cuba’s Community Based Rehabilitation Program feel that with access to more detailed, appropriate information they could better help disabled children and adults meet their needs.

HealthWrights has made a commitment to try to supply copies of Disabled Village Children and Nothing About Us Without Us in Spanish to all of the 120 Activistas. They can’t afford to buy them, as the basic wage in Cuba is $5 a month. The books are produced and can be sent from Mexico. We need help to cover the costs. US $12 will provide one Activista a book. $48 will provide 4 books, or $96 will provide 8 books.

Help us show the Cubans that not all North-Americans are blind to its achievements, or what it has to share with and teach the world.

Conclusion

In closing this commentary, I would like to refer to “Cuba: a Reflection on the Meaning of History” by Jay Edson. This article serves as the introduction of the Cuba section of the Politics of Health web page.

In looking at the long range history of Cuba, before and after the arrival of Columbus, Edson speaks of the indigenous inhabitants of Cuba, the Taino. He refers this original population of the island—who lived close to the soil and made clay pottery—as “the people of clay.” This group is contrasted with “people of iron”—the colonial conquistadors whose swords and guns, and crucifixes as well, were made of metal. The “people of clay” were relatively “fragile and easily broken,” whereas the “people of iron” have a hardness that breeds conflict and causes injury. Clearly there is no going back. But the world run by the “people of iron” has run into difficulties. In some ways the people of Cuba, held together by their revolutionary spirit and their will to survive the aggression the US superpower, are seeking to rediscover and build on those down to earth traditions of their predecessors, the “people of clay.” They are molding ways to live in sustainable balance with the natural environment and to treat one another more as equals. The world can learn a lot from this truly revolutionary and evolutionary endeavor.

Update on PROJIMO

In 2004 exciting things are happening in both PROJIMO programs in rural Mexico.

In the PROJIMO Rehabilitation Program, in Coyotitan, one big advance has been an arrangement with the Barr Foundation, based in Florida, to provide high quality prostheses free to poor people who need them. Components are donated by the Barr Foundation, which also, with help from the Culiacan Rotary Club, contributes to the production cost. Marcelo Acevedo and Conchita Lara, disabled members of the PROJIMO team, have already fitted 9 of the first 20 amputees.

The Culiacan Rotary Club became more closely involved with PROJIMO and sponsored an upgrade of the entire physical plant, together with construction f a new therapy room.

The Intensive Conversational Spanish Training Program, taught by Julio Peña, Rigoberto Delgado and, most recently, Gabriel Cortez—all 3 functionally quadriplegic—is attracting more and more students. Ranging from the US, Canada, and England to Holland, Japan, and India, most come to volunteer as well as to study, sometimes with the whole family. Children have a great time playing with and learning from the village children. Please consider coming to study Spanish at PROJIMO. And help us spread the word. It helps disabled folks earn a living—and helps the program.

At the HealthWrights board meeting in April 2004, we discussed the enormity of PROJIMO’s contribution to disabled children and adults in Mexico. Mari and Conchita, the program coordinators, figure that PROJIMO has served over 30,000 disabled persons. Annual donations for PROJIMO total about $50,000 a year. But the value of the services provided is much higher. The 40 or so limbs Marcelo and Conchita will make this year would cost in the USA around $200,000. Value of all services and equipment provided each year would run over half a million dollars. In urban rehab centers in Mexico costs would run half that, but vastly more than in PROJIMO. Poor families would go without.

Donations of crucial medical supplies have been substantial in value as well. For example, over the past eight years donations of Colting Factor 9 for Carlos Garcia, a boy with hemophilia B, have a value over $160,000. Without this life saving medication, Carlos could not walk and was in constant pain. With it, he has been able to lead a normal life.

Add to this value the influence PROJIMO is having worldwide through networking, educational exchanges, and wide use of the books Disabled Village Children and Nothing About Us Without Us, the impact of the program is enormous.

The PROJIMO Children’s Wheel-chair Program in Duranguito is also making big advances. The new welding and car pentry workshop has been completed with help from Stichting Liliane Fonds in Holland and several government programs in Mexico. The village team, which custom designs and builds wheelchairs to meet the needs of each child, has received two awards at the state and national levels. The state Family Development Program (DIF) is now contracting with PROJIMO Duranguito to build large numbers of individualized wheelchairs for children in various parts of the state. The governor’s wife, after attending the presentation of 23 wheelchairs to children in Cruz de Elota, has donated a new arc welder worth $1,500

The state of Nayarit, to the south, is also involved. Groups in several states (and other countries) are arranging for disabled persons to apprentice in Duranguito, and then set up their own workshops. At last the idea that children deserve a wheelchair that actually meets their needs is beginning to catch on!

The two coordinators of the PROJIMO Wheelchair Program, Gabriel Zepeda and Raymundo Hernandez—both wheelchair users—are to be applauded for their accomplishments, as is their entire team. *

* See a slide show of custom-designed wheelchairs made at PROJIMO Duranguito on www.heathwrights.org.

End Matter

Please Note! If you prefer to receive future newsletters online, please e-mail us at: newsletter@healthwrights.org

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing |

| Efraín Zamora — Design and Layout |

| Trude Bock — Proofreading |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |

| Jay Edson — Writing |

One just principle from the depths of a cave is more powerful than an army.

— José Martí (1853-1895)