WHERE ARE THE SLIDESHOWS FROM INDIA? SEE INSERT

Community Based Rehabilitation in Rural India: the Strengths and Weaknesses of Different Models

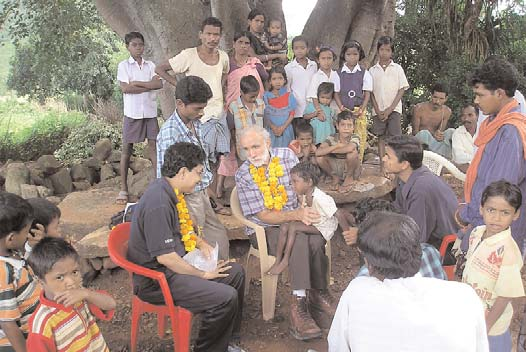

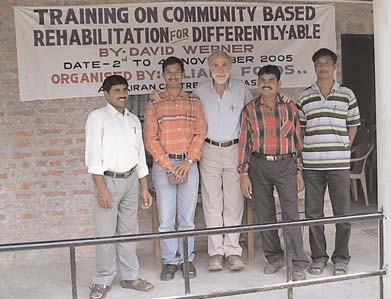

In October and November 2005 David Werner was invited to India to facilitate three Community Based Rehabilitation workshops in the Creation of Low-cost Technical Aids. These hands-on workshops were attended by local “mediators” of Stichting Liliane Fonds (SLF), a Dutch foundation dedicated to helping disabled children living in difficult circumstances. Since SLF has been assisting disabled children in Mexico through PROJIMO for many years, this was a chance for David to return some of the goodwill. Here he relates the experience and raises questions about different models of Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR).

Contrasting Models of CBR

Today India has hundreds of so-called Community Based Rehab (CBR) programs that are striving, in a wide variety of approaches, to meet the needs of disabled persons living in rural areas and also city slums.

CBR was first conceptualized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the early 1980s as an inclusive methodology to deinstitutionalize rehabilitation activities and take the front line response to disability out of costly urban “rehab palaces” and into villages and homes.

Initially the WHO model of CBR was precisely—and in some ways rather rigidly—defined. But fortunately, over the last two decades, CBR has evolved to embrace a diversity of approaches. Various models have been designed in response to differing needs and possibilities in different regions and communities. Much can be learned by comparing the strengths and weaknesses of these different approaches.

On my recent visit to India, the three workshops I facilitated—in northern, central, and southern India—were coordinated by NGOs following quite different models of CBR, each with respective strengths and weaknesses:

-

The first workshop was held in the village center of Vikash CBR Program, located among the “hill tribes” in the District of Koraput in the central eastern state of Orrisa. Koraput is reputed to be the poorest district in India, and its tribal people, belonging to the so-called “scheduled castes,” are among the nation’s most marginalized. The combination of poverty, malnutrition, endemic diseases (especially malaria), and congenital defects due to inbreeding contribute to high rates of disability.

-

The second workshop, organized by Jan Vikas Samiti, a development program, was held in the Kiran Village Rehabilitation Centre, in a rural area 2 hours from Varanasi (formerly Benares) in Uttar Pradesh. These two programs collaborate in a CBR initiative in the surrounding rural area.

-

The third workshop, held in Nalgondo near Hyderabad, was coordinated by the Network of Persons with disAbilities Organizations of Andhra Pradesh, (NPdO) which runs a “human rights” approach to CBR rural area.

Let us look at the strengths and weaknesses of these initiatives.

Seeking a Balance Between Social and Technical Aspects of Rehabilitation

One of the strengths of Community Based Rehabilitation, at least in theory, is that it seeks a balance between the technical and social aspects of rehabilitation. Whereas institutionalized rehabilitation services have conventionally focused on technical or biomedical interventions and largely ignored the social concerns, CBR emphasizes the latter. It focuses on community awareness raising, mainstreaming of disabled children into schools, skills training, and work possibilities: in short equal opportunities for all.

However, a major weakness of many CBR programs in most countries is that, whereas social rehabilitation is often fairly well developed, the technical side has often been neglected. That is to say that the physical needs of disabled persons—ranging from individual therapeutic assistance to assistive devices—are often poorly or inappropriately responded to.

The Achilles Heel of Community-Based Rehabilitation

One reason for the technical inadequacy of many CBR programs is that the local workers are usually part-time volunteers who receive very little training. Because their CBR activities are unpaid, they must fit them around their other work and home obligations. Thus they never get enough experience to gain the skills and confidence necessary to respond adequately to the therapeutic and technical needs of those they help. Consequently, many disabled persons fall far short of meeting their potentials, physically and therefore socially.

Ideally, to make up for their limited training and experience, CBR volunteers should have sufficient skilled backup and referral possibilities so that the therapeutic and technical needs of disabled people can be met. But too often the support system is ineffective or nonfunctional. As a result the many crucial needs of disabled persons remain unmet. E.g., children who have a potential for walking never do. Spastic infants who need a seat that positions them so they can swallow food without gagging die of pneumonia or hunger. And too often the exercises or “physiotherapy” applied to disabled persons is nothing more than a standardized ritual that has little to do with the actual needs of the individual.

Different Approaches to Meeting the Technical Needs in CBR Programs

All of the 3 CBR initiatives where I facilitated workshops in India had a fairly similar approach to addressing the social needs of disabled persons. They all had community awareness raising campaigns to encourage greater inclusion and respect for “persons with different abilities.” They all made efforts to integrate disabled children into the public schools. And they all had skills training and “micro-finance” schemes to help disabled persons and their families increase their income.

But when it came to meeting technical and therapeutic needs, the 3 programs took quite different approaches, as follows:

1. Vikash CBR Program in Koraput, Orrisa

Vikash CBR Program in Koraput, Orrisa, has a front-line cadre of village CBR “activists” who, rather than being part-time volunteers, are employed full time with modest salaries (paid for by Action Aid). The activists, in turn, are backed up by a comprehensive team of rehabilitation professionals that includes special educators, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist, a speech therapist, a psychologist, and a prosthetist-orthotist, all of whom devote much of their time visiting and advising the activists. The strength of the program is in the area of social integration with emphasis on education of children and income generating training opportunities for adults, including a tailoring shop and bakery. A preschool program run by well trained, very caring village women (2 unmarried sisters) does an excellent job in preparing disabled children—including deaf and blind children—for school.

The Vikash CBR Program, with its paid full-time activists and professional support team, provides a scope and quality of services better than many other programs. However its annual budget, which works out to $80 per disabled person served, is higher than India’s per capita health budget, and therefore probably not a realistic model for scaling up to a national level.

Also, although this program has a professional back-up staff including a physiotherapist and a limb-and-brace maker, to my surprise we encountered children with club feet that could have been corrected long before with serial casting, and persons in the tailoring program who had one leg paralyzed by polio and walked with poles, whereas they could have walked more easily with crutches.

2. Jan Vikas Samiti, and Kiran near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Jan Vikas Samiti (JVS) is a “social work” organization of the Varanasi Province of The Indian Missionary Society. It works primarily for the enablement and livelihood enhancement of women living in slums and rural areas. However it now includes an extensive Community Based Rehabilitation initiative assisted by Liliane Fonds. Although the main focus of the CBR program is in the social area (daily living skills, schooling, and “livelihood” opportunities), for the technical side of rehabilitation the program seeks the help of Kiran.

Kiran “Children’s Village” is a large rural rehabilitation center founded by a former nun from Switzerland. The spacious campus includes a school for children with all disabilities (which prepares them for entering public schools), various skills training shops, and a well equipped orthopedic and prosthetic workshop. It has a very capable professional staff covering a wide range of rehabilitation skills. Of its many good technicians, several are disabled. Kiran also has a community outreach program, which works closely with the JVS CBR program.

As result of the collaboration between Jan Vikas and Kiran, this initiative has the best balance between the social and technical aspects of rehabilitation, and the highest quality of services that I encountered on this visit to India. However, at an annual cost of at least $50 per child assisted, the program would be hard for the government to replicate (at least without cutting back on India’s military spending).

3. Network of People with disAbilities Organizations of Andhra Pradesh (NPdO), Hyderabad, AP

The SLF workshop outside of Hyderabad was organized in collaboration with a statewide organization of “disabled activists”, NPdO, that has launched a CBR program in the rural area. Run completely by disabled persons, until now the focus of the program has been entirely on “issues”—that is to say on awareness raising and demands concerning the rights and opportunities of disabled people.

The NPdO has worked hard to inform disabled persons of their legal rights to education, health care, reduced bus and train fares, economic aid, and other “entitlements.” But in terms of the therapeutic and technical needs of disabled persons, they have done almost nothing. They say they help disabled persons apply to government services for needed surgery, therapy, and assistive equipment. But the results have been almost nil. We saw numerous people in the area crawling or hobbling with sticks who could have managed much better had they received timely therapy and assistive equipment. But there was virtually no therapy happening. And except for one pair of badly adjusted crutches, the only assistive equipment we saw were large hand-powered tricycles—many of them unused because they didn’t meet the needs of the recipients.

Failure of the World Bank Disability Initiative in Andhra Pradesh

In 2002 I went to India as an advisor to the disability component of the World Bank sponsored “Andhra Pradesh Rural Poverty Reduction Program.” At that time many plans were made to help disabled people meet their most pressing needs. But in 2005, at least in the part of rural Andhra Pradesh we visited, disabled people’s needs remained almost totally unmet. The NPdO tries to help people obtain their legal rights, but even that is a frustrating uphill battle.

Fortunately, the disabled leaders of the NPdO who participated eagerly in our workshop are committed to learning more about disabled persons’ technical needs and helping families produce appropriate low-cost aids. They agreed to send me photos of their work. If the NPdO, with its thousands of members throughout Andhra Pradesh, takes on this challenge, it may prove to have a greater impact on the enablement of disabled persons than all the costly inputs of the World Bank.

Problems and Concerns Observed in All the CBR Programs Visited in India

1. Where Have All the Severely Disabled Children Gone? And the Girls?

In the hands-on workshops I facilitate in Latin America, there are always young children with severe cerebral palsy (CP) or multiple disability who can benefit from individually designed special seating. With these children we introduce the construction of special seats made with layers of cardboard pasted together (paper based technology).

I was eager to introduce these cardboard seats to the SLF mediators at our workshops in India. But in rural areas, we had a hard time finding children with severe enough disabilities to need them. I saw far fewer children with CP than expected. And of those I saw, their disability ranged from mild to moderate. I asked if the more severely affected children were kept hidden away by their parents, but was told no: the local CBR workers know every family and had detected every child.

The answer, most agreed, is that severely disabled children are often allowed to die —especially those born disabled—and especially girls. We saw far more disabled boys than girls than can be accounted for by the fact that in the general population boys outnumber girls due to amniocentesis (sex determination before birth) and provoked abortion of female fetuses.

Such problems have deep social roots, but are also linked to the pervasive poverty. Participants pointed out that the rights of disabled persons are closely tied to the basic rights of the people as a whole. This is why CBR increasingly emphasizes human rights as well as the overarching problem of poverty and undernutrition.

2. Assistive Devices That Don’t Meet the Users’ Needs

As in many countries—but in India more than most—much of the standardized equipment provided to disabled folks by the government (and even by NGOs) is inappropriate for the person’s needs. And in some cases the basic design is faulty:

Crutches

Nearly all the crutches we saw people using in India were poorly adjusted. The hand-grips are adjusted far too high, so that the person’s elbows bend at 90 degrees. This makes it much harder to bear weight on the arms, and leads to the person hanging by their armpits, which is more tiring and can cause nerve damage.

|

|

|

|

A big cause of poorly adjusted aluminum crutches is that they are poorly designed. Even the lowest possible adjustment of the crutch hand-grips is far too high. OLIMCO, the government company that makes assistive devices, should redesign them so they can be easily adjusted for easier use.

In our workshops several persons’ crutches were readjusted by drilling new holes and lowering the hand-grips. The users were delighted with how much easier it was to walk.

|

|

|

Parallel Bars

Like the crutches, most parallel bars we saw were adjusted far too high, and also too far apart, for most children’s needs. This was the case even in the Kiran Center, where most of the therapy and rehabilitation was excellent.

For example, Ajit has spastic CP. Kiran helped the family build parallel bars for him to practice walking. But the bars were much too high and far apart for him to help support his weight on his arms.

|

|

|

During our workshop, at the Kiran Center the group tried adjusting the bars to a better position for Ajit. But the lowest adjustment was still much too high. So they raised the floor between the bars, until at last Ajit was able to stand straighter and more comfortably.

In our village visits we saw many persons with a paralyzed leg walking with poles, like the girl here. Many had never had the opportunity to use crutches. But others preferred the poles because the crutches with their high hand-grip were too hard to use.

It appears that the custom of poor adjustment of crutches and parallel bars is so deeply ingrained that even many highly trained experts accept it without question.

Now that the Network of disAbled Persons Organizations has become aware of the problem, they are determined to persuade OLIMCO to redesign their crutches so that the hand-grips can be correctly adjusted.

3. Tricycles and Wheelchairs—a Mixed Blessing

Hand-Powered Tricycles

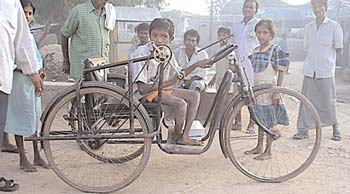

India is famous for its hand-powered tricycles. You see them everywhere. In cities and villages where rough roads and sand bogs make wheelchair use a nightmare, these tricycles with their huge wheels make mobility much easier—at least for those with the ability to use them.

However, most of the tricycles, like most wheelchairs, come in one, giant size. In campaigns of public charity they are given to anyone with a physical disability, whether the person can use one or not—a big frustration and huge waste of money!

Wheelchairs

Wheelchairs, although much less common in India than tricycles, suffer the same problems seen in many poor countries. They tend to be big and too box-like, especially for children. Jayaram is a 6-year-old boy with CP who was given a wheelchair far too big for him that increased his spasticity. In the Koraput workshop the mediators made a seat out of layers of cardboard. The seat inserts into his big wheelchair and lets him sit more comfortably, with less spasticity, in a better position.

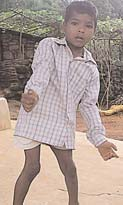

But in the hill country where he lives, a wheelchair is of limited use. What Jayaram wanted to do was walk. But his uncontrolled movements made him fall every time he tried to stand or walk.

In the home visit, the mediators discussed various possible walking aids for Jayaram. But in the rough terrain where he lives, a walker or even a cane with tripod feet seem unlikely to function. At last they tried a simple walking stick. To everyone’s amazement, with the stick the boy was able to stand quite steadily and walk without falling.

|

|

|

|

So in the workshop they made him a colorful walking stick with a ring near the top to keep his hand from slipping.

Special Seats

Although we saw little by way of special seating in the areas we visited, the few seats we saw—though made with professional’s guidance—were unsuited for the children. Typical of institutional seats for disabled children in many countries, they were box-like, uncomfortable, ill-fitted, and did more to trigger than control spasticity.

For Suresh, a boy with CP in Koraput, a seat had been made that was so unstable and poorly designed that his mother, wisely, didn’t use it.

In the workshop the mediators cut off the legs of the seat, tilted it back to a better position, and built a cardboard insert, as well as a table. Now Suresh sits much better.

Examples from the CBR Appropriate Technology (Assistive Devices) Workshops

NOTICE: A detailed, colorful photo-documentary of these hands-on Workshops can be viewed on our website: www.healthwrights.org. It is also available from HealthWrights as a CD. See attached insert.

The three 3-day workshops in India with mediators of Stichting Liliane Fonds were structured similarly to those I facilitated in Nicaragua in May 2005 and described in our previous Newsletter (#53/54)—which can be viewed at: www.healthwrights.org.

The Workshop was Organized as Follows

-

1st day involves discussion about CBR with examples from different countries. Partnership in problem solving is emphasized.

-

2nd day starts with principles and examples of low-cost assistive devices. This is followed by small group visits to the homes of disabled children, to explore with the children and families what simple aids might help each child function better.

-

3rd day begins with a plenary brainstorming of ideas and designs. Then each group, together with the child and family, construct the aid. The day ends with an Evaluatory Session where each child and parent with their group shows how the aids work—and everyone makes suggestions.

-

Collaborators: In each workshop the local staff of the collaborating CBR programs was a great help. In addition, the assistance of local craftspersons (carpenters and bamboo artisan) was invaluable in making the aids.

In the next few pages we will show some examples of the workshops and the resulting assistive devices.

1. Koraput Workshop

Trinath

Trinath is a young man who is apprenticing in the tailoring shop of the Vikash CBR program. With one leg weak from polio, he walks pushing his weak thigh back with his hand. His wish was to walk without having to push his leg back.

Trinath and the mediators decided to make a night splint to gradually stretch the contractures in his knee, in hopes this may help. With the help of a local artisan they made a night splint out of bamboo.

They cut a piece of bamboo to size, hewed out part of the inside, and heated the top part to widen it to fit his thigh. Then they covered the inside with soft padding and added Velcro straps.

The bamboo night brace fit so well that he decided to try walking with it.

|

|

|

Bhararthi

Bhararthi is a young woman, also in the tailoring shop, who has one leg affected by polio She walked with a pole. She had never used a crutch but was eager to try, so she could walk with one hand free to carry things.

Bhararthi was very pleased with her new crutch, especially when it was adjusted with her elbow nearly straight so she could bear part of her weight on it.

|

|

|

A Toilet for David Werner

One person who wanted an assistive device made for him at the Koraput workshop was myself (David W.).

With the disability I have in my legs and feet (a hereditary muscular atrophy) I have trouble with

toileting in India. Traditionally people squat over a hole in the floor, or simply go out and squat in the fields (a common cause of fatal snakebite at night).

When I suggested that, like myself, many disabled persons might appreciate a toilet they could sit on, one CBR leader in Koraput said that such an idea would be unacceptable or even shocking to the local villagers. Besides, it wasn’t something you talked about.

Nonetheless, a group of mediators made a simple toilet seat for me: a wooden box with a hole, which I could put over the hole in the floor.

When I demonstrated my new toilet at the final session of the workshop, everyone laughed. But it broke the ice, and many disabled persons began to ask for toilets in the subsequent workshops.

2. Hyderabad Workshop

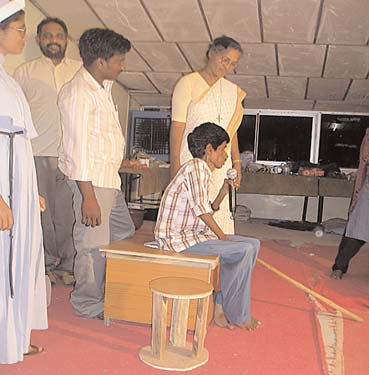

A Toilet for Panasa

Panasa is a young man with progressive muscle wasting. He is very weak and walks with a pole. He insisted he was too weak to use crutches. But what he said he most wanted was a toilet.

So the mediators made him one, with a stand for his wash water pot. Here he demonstrates it at the final evaluation.

Whole Villages Disabled by Flourosis

Another group that eagerly wanted toilets, but who had never dared ask for them, was people with fluorosis. This strange disability with gradually progressive weakness and joint deformities comes from too much fluorine in the water. Most people in over 260 villages in Andhra Pradesh are affected.

Although people know the local water is crippling them, until recently, few have had an option. Today bottled drinking water in India is mostly controlled by Pepsi and Coca Cola, and a liter sells for one and a half the price of a liter of milk.

|

|

|

Recently, however, an NGO has been introducing collection and storage of rainwater from roofs. Also the government is now building a big dam to pipe fluorine free water to the stricken villages.

Too Many Nosy Experts; Too Little Help

One family we visited, in which the husband, wife and children are affected by fluorosis, lost their patience when we visited. They told us angrily that they were tired of being visited by international experts who asked embarrassing questions and took pictures of them, but never did anything to help. But at last they warmed up to us. With many of these people, the idea of toilets they could sit on, and the fact that other disabled villagers were daring to use them, was a very welcome idea.

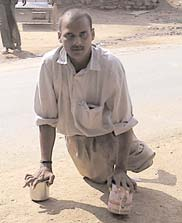

Mobility Aids for Venkatesham

|

|

|

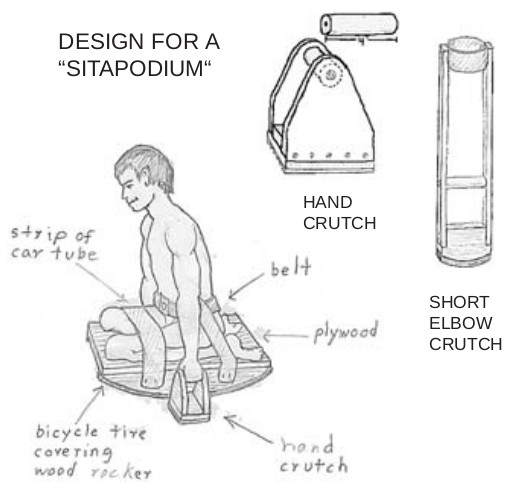

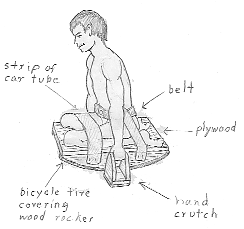

Venkatesham (Venki for short) is a man who moves about by crawling. Although his legs are paralyzed and contracted by polio, he is able to support his family by managing a small sidewalk shop and a public phone. He has a wife, and two beautiful children.

Although the mediators tried to convince Venki that he needed a tricycle or wheelchair, he wasn’t much interested. He explained that he had to go many miles by bus to buy supplies for his shop, and wanted simple mobility aids he could easily take with him on the bus.

He suggested short “hand crutches” to make crawling easier and cleaner. He demonstrated his idea gripping 2 cans.

Venki also wanted some kind of knee and butt protectors. This led to a variety of ideas, including a small wheeled “skate board,” and a “rocker board” he could sit on to move about by swinging through between his arms. This rocker board or “sita-podium” could be used in mud and fields (for toileting) where a wheeled board won’t work.

The different ideas and designs, were presented to the plenary on the morning of the workshop.

The mediators made the hand crutches while the local carpenter made the wooden wheels and axle bars using hand tools, while gripping the wood in his bare feet.

|

|

|

At the end of the workshop Venki showed everyone how he could move about on the board.

Clearly, this wheeled board won’t survive hard use. But Venki plans to replace the wood wheels with better ones with bearings. What matters is that he has started experimenting and taking the creative lead himself.

Thoughts on the Hyderabad Workshop

The Hyderabad Workshop was in some ways the most difficult of the three, for a combination of reasons.

-

First, the collaborating CBR program, run by the Network of Persons with disAblities Organizations (NPdO), lacked the technical skills of the other collaborating CBR programs in Koraput and Varanasi.

-

Second, the SLF mediators in Hyderabad were mostly administrators and managers, not field workers. While very attentive about all the theory of technical aids and the creative design of devices, when it came to hands-on construction they were all thumbs. The less high ranking participant in the other workshops tended to be more pragmatic and down to earth.

Consequently, while many of the designs in the Hyderabad workshop had great potential, the aids actually produced were often less than functional, either because of construction errors, or because it took so long to complete even the most basic tasks. But all agreed that the workshop broke the ice in terms of creating low cost aids, and that it was a great learning experience.

3. Veranasi Workshop

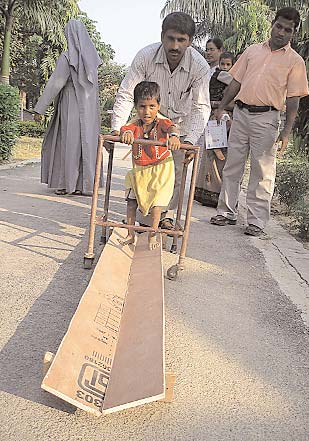

Helping Kiran Learn to Walk

Kiran is a 5-year-old girl with cerebral palsy, who is just beginning to walk with the help of a metal walker provided by the local rehabilitation center—which is also called Kiran. Kiran means ray of sunlight.

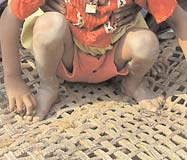

With the help of her doting grandfather Kiran is able to take steps with the walker. But the spasticity of her lower limbs causes her feet to bend bend over to the side.

Clearly Kiran needs foot and ankle stretching exercises to help her feet stand flat on the ground. The group asks her grandfather to show the exercises he has been taught. Although he does them well, most are routine “water pump” exercises that do not focus on the specific needs of the child.

|

|

|

|

However Kiran’s mother knows and demonstrates the foot and ankle stretching exercises that are most important for the girl to walk with her feet positioned well.

But unfortunately no one has been doing these exercises with the child.

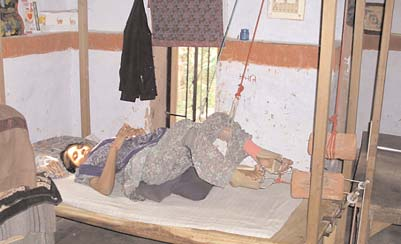

Then a discovery is made. When Kiran squats on the cot, the U-shaped sagging of the cot positions her feet well, stretching them up and outward, in precisely the exercise she most needs!

|

|

|

Following the stretching mechanism of the cot, the mediators made a V-shaped trough of boards for Kiran to walk on.

To make this aid at home at low cost, Kiran’s grandma helped make a V-shaped ditch with bricks—and bamboo parallel bars.

In the final plenary, Kiran demonstrates how well she can walk. Each step stretches her feet for better walking.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kiran’s story shows us the importance of knowing the family situation, working together, and using local resources creatively.

Shubham’s Story

Because in the rural area surrounding Varanasi no young children could be found with severe cerebral palsy, the coordinators of Kiram Village took us to see a multiply disabled child in the city. Six year old Shubham lives in a different world than his rural, low caste peers. He belongs to an upper caste Brahman family and lives in a relatively luxurious flat. His father works in the US.

Shubham is multiply disabled. He has cerebral palsy (mix of spastic and flaccid), is mentally retarded, and has visual and hearing impairment. The boy’s mother and grandmother are devoted to him and have sought help widely.

A rehab center made this special seat for Shubham but it doesn’t meet his needs:

-

It is straight up and down like a box,

-

too wide, and

-

the footrest is way too low.

The mediators who visited Shubham decided with his mother to make a more appropriate seat with stimulation toys, an exercise role and a hammock. Here they present their designs to the plenary.

|

|

|

|

To make the chair

-

They built the seat out of a combination of wood, plastic, and cardboard (L).

-

At first the boy flopped to one side, so they made cardboard body supports (C).

-

They made a cardboard cushion with a hollow to keep his butt from sliding forward (R).

-

Finally, they added a cardboard footrest (R).

Other Aids Made for Shubam

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shubhan’s family were delighted with the new aids—and felt they had a better understanding of his needs and what they can do.

Reflections on What it Means to be Disabled in India

India and its people (or at least some of its people) have been close to my heart since I was very young. In my childhood my mother, who studied under the Indian poet philosopher Rabindranath Tagore when he was a guest professor at Harvard, used to read me his Crescent Moon Poems. As a boy I began to form a dream of the Orient, and especially India, as a place where people were kind and lived in harmony with each other and with nature. In my 20s I traveled to India overland from Europe on a bicycle, in pursuit of that Eutopian dream.

The dream was of course a dream. India is a land of contradictions—of great humanity and inhumanity. But in India people’s dreams and nightmares seem more real, or at least they are driven by them. My youthful journey to the East had a deep impact on me and has determined the direction of my life ever since. By the time I first went to India the non-violent revolutionary, Mohandas Gandhi, had already been slain. But his spiritual successor and leader of the Bhudan land reform movement, Vinoba Bhave, was still walking the face of India recovering millions of acres of land from the rich, for the landless. The Nai Talim schools—which Gandhi and Vinoba set up to enable untouchable children to survive with dignity in a world that denigrated them—were still going strong. My exposure to Vinoba and Nai Talim opened the way to my later involvement in alternative education, and then to my lifelong struggle for the health and rights of marginalized people.

I have revisited India several times in the last few decades. Each time I return, some part of my soul reignites. There is much love, kindness and beauty in India. But the crushing poverty in the face of wealth remains overbearing.

In his recent book, The End of Poverty, economist Jeffrey Sachs celebrates India as a country whose recent immersion into the global economy has launched it on the long road to prosperity. Poverty, he asserts, will retreat as economics grows.

But economic growth in India has left hundreds of millions behind. Perhaps the claims are true that fewer people live on less than one dollar a day. Yet many I talked to in India say that the poverty and powerlessness of the poor is getting worse. As the water table drops with industrialization, and climate change causes increasing floods in some areas and droughts in others, more and more farmers are committing suicide. For the few improvements that peasant farmers have realized in terms of land use and fairer treatment, many people I talked with give more credit to the Naxalites (Maoist Guerrilla movement) than to the World Bank. Indeed, in Andhra Pradesh, where the Bank has its model program to benefit disabled people, the disabled persons I met had fewer services and benefits than those in the other parts of India I visited.

In short, the basic needs of hundreds of millions of people in India remain unmet. Millions of children are under-nourished. Rich countries dump their surplus grain on India at subsidized prices, which forces Indian farmers off the land. Meanwhile, vast amounts of stored grain rot while multitudes go hungry.

No, India is not free from the increasingly globalized shackles of the Northern powers. Gandhi would turn in his grave.

The World Health Organization states that one of the biggest causes of disability is poverty. But in a rigidly stratified society, poverty itself is a disability.

This is why the Network of Persons with disAbilities Organizations (NPdO) in Andhra Pradesh takes a “rights based approach” to rehabilitation, and feels that they must struggle for equal rights and equal oppor- tunities of all peoples, including those of the women, tribals, the underclass, the scheduled castes (untouchables) and others who are left out of what is mistakenly called development. More power to them!

PROJIMO Film Wins Awards: Return to Life After Spinal Injury

Return to Life After Spinal Injury, the new DVD by Peter Brauer, won two International Health and Medical Media awards, or “FREDDIES” at the 31st annual award ceremony in New York City on November 4th. This Spanish language instructional video about spinal injury took top honors in the category of “Special People”, and won the prestigious Helen Hayes Award for best consumer video production. The Helen Hayes award is one of four Founders’ Awards given to the best films in the contest.

This empowering educational production was conceived and produced for and by spinal cord injured persons themselves, as a graphic form of peer counseling. Filmmaker Peter Brauer spent 3 months working with the PROJIMO team as a collective learning experience for all. And because everyone volunteered their time and the filming was digital, the cost was remarkably low.

These disabled educators who have created this CD—ranging in age from 10 to 40—skillfully show how to prevent and treat pressure sores and urinary infections, how to avoid and correct contractures, and how to make low cost protective cushions, and assistive equipment. But above all they show how spinal cord injured persons can relearn the skills of daily living, find ways to earn a living, and re-enter the life of the community as active participants and leaders.

This astounding CD film will give a great boost to persons with recent spinal cord injury, to help them accept their disability and realize that they can still live rich and fulfilling lives.

Spanish, with English Subtitles: US$22 plus $3.00 shipping. Profits go to PROJIMO.

End Matter

Please Note! If you prefer to receive future newsletters online, please e-mail us at: newsletter@healthwrights.org

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing and Design |

| Jason Weston — Layout |

| Trude Bock — Proofreading |

| Jim Hunter — Review |

Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness … the energies of love, and then, for a second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.

—Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Insert

Donations Needed for Future Hands-On Workshops

In the last few newsletters, David Werner has reported on the hands-on workshops he has facilitated in Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) programs in India and Nicaragua. He has also led such workshops in Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia and Mexico. David’s unique way of working with and involving disabled persons, their families, therapists, and rehabilitation workers in the problem solving process is a real eye-opener. These workshops demystify the technical side of rehabilitation and help participants design and make assistive devices that meet individual needs at low cost.

Results are impressive. Sometimes children who have never walked before take their first steps with a walking board (parapodium). Or poorly designed crutches are adjusted for easier and safer use. And teams of disability workers learn the importance of listening to the needs and desires of the disabled persons they assist.

David is now 71 years old and finds these trips more tiring—though very rewarding. HealthWrights would like to have someone accompany him. Jason Weston and Bruce Hobson, who have worked with HealthWrights for many years, would like to start going with David on some of his trips to observe and assist in the workshops, with an eye toward eventually conducting them independently.

However, with their modest HealthWrights salaries, they cannot afford it. The groups that invite David for these workshops usually are not in a position to pay for additional airfares and accommodations. So we are turning to you, our long time friends, for help and asking you to make a special year-end donation so this work of conducting interactive hands-on workshops can continue and grow.

Three New CBR Slide Shows, Online and On CD

The recent CBR workshops in India provided material for three new extensive slide shows, each with captions detailing the interactive process of the workshop participants, the disabled individuals, and their families. These heartwarming, yet pragmatic stories show how, working together and putting the disabled person at the center of the process, assistive devices can be tailor made to better fit his or her needs.

See www.healthwrights.org/publications.htm for downloads, or order the CD from the other side of this flier.

PROJIMO Wins National Award

The Mexican Volunteer Association has selected PROJIMO for its “extraordinary work in favor of the most needy,” and awarded its National Prize for a Charitable Organization in 2005. This month Conchita Lara will travel to Mexico City, where she will receive the award from Mrs. Marta Sahagún de Fox, wife of Mexican President Vicente Fox.

PROJIMO Rehab and Wheelchair Programs Need Assistance

The PROJIMO Rehabilitation in Coyotitan has lost its main funder: Brot Fuer Die Welt in Germany. BFDW has been extremely generous, exceeding by many years its own guidelines for how long to support an individual program. It has assisted PROJIMO since 1981 and will definitely stop at the end of this year (2005). Although PROJIMO is now getting more recognition and support within Mexico, it still needs donations to help make ends meet.

The Children’s Wheelchair Program in Duranguito is getting increasing numbers of orders from various programs in Mexico. Although Stichting Liliane Fonds in Holland pays 60% of the cost and families pay something, HealthWrights still helps with supplies and equipment. Please be as generous as you can.

Spanish Training Program at PROJIMO

In rural Mexico in the village of Coyotitan, 40 miles NW of Mazatlan.

-

Learn conversational Spanish in a rural setting.

-

Volunteer in an innovative, empowering, community-based project.

-

Begin any time. Stay as long as you choose.

-

Individual instruction by disabled villagers.

-

Live and practice Spanish with a local family.

-

Typical Mexican food (vegetarians welcome).

-

Health workers, activists, and disabled travelers especially welcome.

-

Cost: US$150 per week—room and meals included.

-

Wheelchair accessible.

For more information on the program, click here.

To arrange a visit, contact the program at:

Proyecto PROJIMO A.C.

Coyotitan, San Ignacio, Sinaloa, Mexico

Tel and Fax: 011 52 (696) 962-0115

Email: PROJIMO_AC@hotmail.com