Workshops For and With Disabled Children in Colombia

The two cities in Colombia where I led workshops on “Community Based Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology” are geographically and climatologically very different. Yet in terms of the vast and growing gulf between rich and poor, they are distressingly similar. The first is the large, rapidly growing city of Medellín, nestled 5000 feet above sea level in a broad bucolic valley in the Andes. The second is the sprawling, sweltering town of Montería, in the lowlands near the Atlantic coast.

I arrived in Medellín several days before the workshop began. I allowed time to visit the homes of disabled children who were candidates for the workshop. My intention was to identify five or six children who might benefit most from simple assistive devices that the workshop participants could make in a single day, with the help of the children and family members.

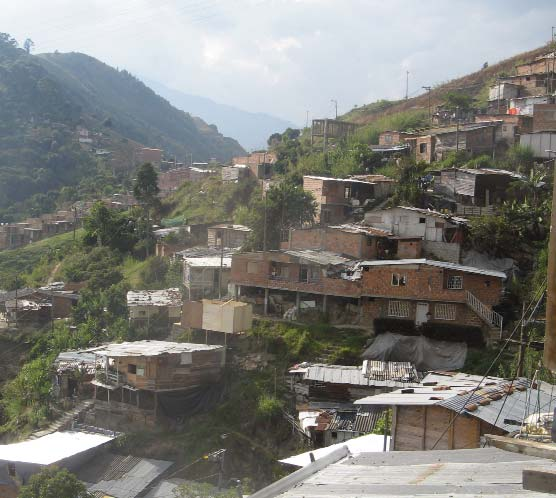

Stichting Liliane Fonds, the Dutch foundation that had invited me, makes a point of reaching out to children in difficult circumstances. Hence many of the homes we visited were in the poorest barrios — clinging to the steep slopes of the Andes, on the impoverished fringe of the city.

“Are you able to climb steps?” asked Sister Teresa, the coordinator of the project, looking at me doubtfully. After all, I’m 73 years old. Also, I have a physical disability, and use orthopedic appliances. I assured her I had no problem climbing steps. I pictured at most having to climb a few flights of stairs to an upper story flat.

Sister Teresa knew from her own experience that it would be much more difficult than I had anticipated. I was unprepared for the perilous geography of the impoverished neighborhoods surrounding the basin of Medellín. These neighborhoods have gradually been ascending higher and higher up the steep flanks of the mountains, for several thousand feet. Much of the terrain is too ragged and perpendicular even for Jeep trails, so the roads are few and far between. To reach the huts where some of the disabled children live, we had to climb hundreds of steps, many that were narrow and precarious, and nearly all without railings. Though I pride myself on still being able to climb mountains (and every summer do so in New Hampshire), I had a hard time keeping my balance on the endless ragged steps of Medellín’s steep slums, and accepted a helping hand from some of the sure-footed locals.

For me coming down the steps was even more difficult than going up. But at least I could manage. For disabled children, however, the shacks they live in, perched high on the steep slopes and separated by thousands of steps from life in the city below, are almost like prisons.

One of the first families I visited had two disabled children, Sandra and Orlando, now young adults. The family’s hut perched on a high ledge among a sea of other shacks. Sandra had a degenerative lung disease and was hooked up to an oxygen tank. Though she could walk short distances, there was no way she could make it up and down the hundreds of steps to the closest road, unless she was carried.

Orlando, her multiply disabled brother, was mildly retarded, spastic, and had multiple deformities of his face, hands and feet. Too heavy for the family to carry up and down the myriad steps, he, like his sister, was in effect under house arrest. He had not left the family hut for 10 years, and is completely isolated from health centers, schools, and rehabilitation services, except for the Liliane Fonds volunteer who periodically comes to visit the family.

Orlando and Sandra’s family—like countless thousands of other displaced families currently subsisting in urban slums and squatter colonies on the fringes of Medellín, Montería, and other cities in Colombia—are in effect internal refugees.

Colombia’s Long Story of Drugs, Violence and Displacement

For the last 40 years, violence has been a way of life and death in Colombia. All manner of armed groups are at each other’s throats. For decades the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas de la Revolución Colombiana), the Colombian Army, an assortment of paramilitaries representing rich land owners, and the powerful drug cartels have been fighting one another. All of these groups have had—and most still have —ties to the multibillion dollar cocaine trade.

The US government has poured billions of dollars of so-called “foreign aid” into Colombia—the lion’s share in the form of weapons and suppor for the Colombian military—ostensibly to facilitate the “War on Drugs.” In reality the primary agenda of the US is to suppress the left-wing insurgency in Colombia. The US has labeled FARC a terrorist organization. Not only does FARC levy a tax on rich landowners and drug growers in the zones it controls, and kidnap key persons as bargaining chips, but it also takes a clear stand in favor of Colombian sovereignty. It opposes the power plays of transnational corporations, the privatization of public services, and the pending freetrade agreement between the US and Colombia.

Despite the billions of dollars that the Bush administration continues to pour into the ‘War on Drugs” in Colombia, the flow of cocaine to users in the US continues at around 250 tons a year. The well-known fact is that the Colombian military has long had ties to the drug trade. Even the current “Get Tough on Drugs” President Uribe has a history of family ties to Colombia’s top drug lords. The US itself has a long history of collusion with drug lords to help finance its covert operations.

There is little question that the insurgents are sometimes brutal. They have recruited hungry children as soldiers, some of them as young as 11 or 12 years old. But the most barbaric treatment of innocent people has been carried out by the government itself, in its so-called “scorched earth policy.” This terrorist tactic has been systematically pursued by government troops and paramilitary groups, many of the latter with ties to the government, the landed gentry, and transnational corporations. To discourage peasants from siding with the guerrillas, whole villages have been burned to the ground, children murdered, and women gang raped. This methodical, strategic violation of human rights, which came to a peak in the 1990s, led to the death of at least 200,000 persons and the displacement of millions. Over the four last decades huge numbers of terrorized families, many of whom have lost loved ones due to violence, have been fleeing the “conflict zones” in the rural area and immigrating to the mushrooming slums of the cities.

Complicating this picture in recent years, the current government of Colombia headed by President Álvaro Uribe has successfully won the favor of the Bush Administration— along with millions of dollars in military aid—by arresting large numbers of supposed drug growers in the rural areas. However, since the drug lords now are well connected in government and in international trade, thousands of those who are arrested, brutalized and jailed are completely innocent.

This pattern of arresting innocent people to satisfy the US government’s demands in the War on Drugs is the same as was practiced in Mexico 30 years ago, when soldiers dragged men and boys out of their houses in the predawn hours, tortured them to confess to drug growing and jailed them by thousands in order to oblige the US demand for “a massive wave of arrests” in exchange for approval of new loans from the World Bank.

The Two Faces of Medellín

Medellín for years was the enclave of Pablo Escobar and the infamous Medellín Cartel. For years it was known as “the murder capital of the world.” In 1992 its homicide toll peaked at 6800 (six times that of Los Angeles’ peak toll of 1,180).

To the modern tourist or international businessman visiting downtown Medellín today, it appears like bucolic oasis. In recent years the wealthy drug lords have cleaned up their image and become respected members of the ruling class. Cartel bosses have metamorphosed into neoliberal tycoons. The opulent core of the city—with its hundreds of sky scrapers, banks, 5-star hotels, luxury homes, discos, and high-rise condominiums—has been constructed with drug money. Coca Cola, McDonald’s, Texaco, and cell-phone towers are omnipresent.

But Medellín also has another, less exuberant face. Surrounding the prosperous central part of the city is its ever-proliferating “septic fringe”—hundreds of thousands of tiny houses and squatter shacks clinging precariously to the steep slopes of encircling mountainsides. The closest I have seen elsewhere to these vertical slums surrounding a bustling metropolis are the notorious favelas of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. As in these favelas, crime, violence and extortion by gangs of thugs and corrupt local politicians are rife.

The city authorities have made some effort to improve the living conditions of this massive influx of displaced persons. They have introduced electricity and water lines into many areas. They have built a few serpentine roads, and in less accessible areas have replaced precipitous footpaths with a bewildering network of crudely made cement steps. On two of the mountain flanks they have even built giant aerial ski-lift-like cable cars to transport people far up and down the mountainside.

But the overall situation remains much the same, and no solution is in sight. Every year, as more and more farming families are displaced by the violence in rural areas, the coveys of squatter shacks inch their way higher and higher up the ragged periurban slopes, and attach themselves to ever more perilous settings. Nearly every day newspapers show photos of “housing landslides” where mountainside shacks collapse on one another in a chain reaction, often killing or disabling the residents.

A Disturbing Initial Finding

On our visits to children’s homes in preparation for the workshops, one surprising finding was that many of the children—even those living in the poorest, most inaccessible shacks—already had a wide range of costly, elaborate assistive equipment. A spectrum of welfare agencies and charitable NGOs, and religious organizations have bombarded the children with a plethora of devices: wheel chairs, baby buggies, standing frames, walkers, and orthopedic appliances.

The problem was that most of this donated equipment was grievously inappropriate in relation to the children’s needs. As I have noted before on visits to other countries, most wheelchairs given to children are far too big for them. As a result, the children are often uncomfortable, sit in a bad posture, have increased spasticity, and cannot realize their potential to move about on their own.

At least two children we saw had developed pressure sores from oversized chairs.

Such ill-fitted wheelchairs are not unusual. But in Colombia the deluge of inappropriate wheelchairs and counterproductive assistive devices was extreme. For this reason, in addition to designing and constructing new devices, we gave a great deal of emphasis to the modification and adaptation of the assistive equipment the children already had.

Logistics of the Workshop

The activities involving each workshop took three days. These workshops in Colombia were organized similarly to those I’ve conducted in other countries.

The first day of the program was focused on the needs of the Liliane mediators. It included presentations on Community Based Rehabilitation and Independent Living, with examples from PROJIMO and elsewhere.

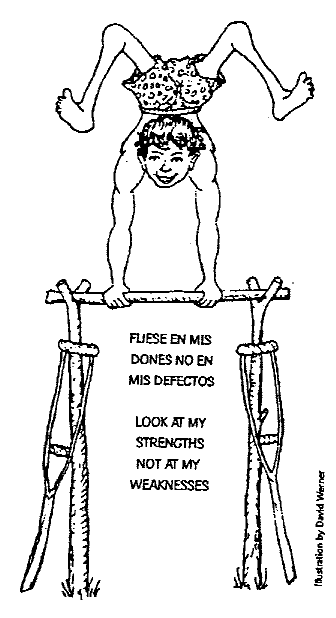

Participants were introduced to Child-to-Child activities that included disabled children, and were shown examples of simple assistive technology. The emphasis of the workshop was on participants working as partners with disabled children and their families, and adapting assistive devices to the individual needs and possibilities of the hild and to the local environment.

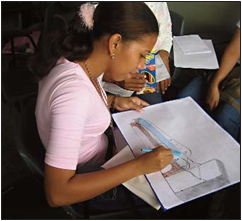

In the morning on the second day the participants (in this case, mediators of Stichting Liliane Fonds) divided into small groups and visited the homes of the children for whom they hoped to make simple assistive devices. Together with the child and family, they decided upon what device or devices to make that could help the child (and family) do things better. They looked at pictures in their books, took measurements, and sketched preliminary designs.

Workshop Schedule

-

Day 1 – Presentations on Community Based Rehabilitation and Independent Living.

-

Day 2 – (Morning) Workshop participants visit the homes of the children.

-

Day 2 – (Afternoon) Small groups work on their plans for the assistive devices.

-

Day 3 – (First hour) Children and family members present their findings and designs.

-

Day 3 – (All day long) The small groups construct and test the assistive device.

-

Day 3 – (Final hour) Presentation of the finished device, evaluations, and conclusions.

Back at the meeting place, the small groups further planned their designs and prepared posters with a summary of their findings and drawings of the assistive equipment they planned to make.

The third day was attended by course participants and the children visited the day before, each with an accompanying family member. During the first hour of the third day we met in a plenary session where each small group, together with the child and family member, presented their findings and designs of the aid they plan to make. Everyone was welcome to share ideas and suggestions.

The rest of the day the small groups together with the child (as much as possible) and family member constructed the assistive device(s) they planed to make, testing it repeatedly with the child for goodness of fit and suitability.

During the final hour we met together as a whole group. The sub-groups demonstrated the (hopefully) finished aids. At this point there was an opportunity for feedback, evaluations, and conclusions.

The Importance of Home-Visits

One objective of the workshops was to help rehabilitation workers realize the importance to adapt assistive equipment, not only to the needs and possibilities of the individual child, but also to local environment and circumstances in which the child lives. This was the reason that we felt it was important that the participants’ first activity was to visit the home and neighborhood of each child. That way they were able to get to know the family and the situation, and discuss with the family the needs and possibilities.

The Children of Medellín

Walter David

Walter David is an alert, friendly 11 year old who is deaf and has cerebral palsy. Until a year ago he used a wheelchair, but now walks with difficulty using a stick.

On my preliminary home visit I examined the weakness and deformity of his feet. I wondered if plastic below-the-knee braces might help him, and showed him the ones I use. He burst into a smile, hobbled into an adjacent room, and came back with a set of braces very similar to my own, that had been prescribed and specially made for him. But he said they didn’t work. Walking with them was much more difficult than without. And they hurt him.

When he put on the braces, the reason was clear. Although they were made by professionals, they were poorly planned. For one thing, they stuck out far beyond the end of his toes. They should have stopped where the toes join the foot, to allow them to bend when he stepped. Because he walks with his knees somewhat bent, the added length of the stiff braces tended to throw him back wards and off-balance with each step. In addition, the sharp edge of one brace dug into the side of foot. No wonder he refused to use them!

I showed Walter David the chapter in my book, Nothing About Us Without Us, that describes how I too, as a child, suffered from wrongly prescribed, badly made orthopedic devices. As if the pain of the braces wasn’t bad enough, I was mercilessly teased by the other children. So apart from being tocayos (having the same name) the two of us felt we had a lot in common. A strong rapport quickly formed between us. His deafness and my lack of sign language proficiency proved no barrier. We understood each other without difficulty.

A small group of mediators visited Walter David and his family in their home. At the plenary the next morning they discussed his problems and wishes. The boy spoke confidently in sign language, and with the help of an interpreter, he conveyed his thoughts and wishes to the larger group. He showed everyone his braces and how badly they fit.

In the workshop Walter David helped cut off the ends of his own braces. First he cut the thick padding off with a knife, and then he helped cut off the hard plastic with a saw. Then we went to the kitchen, and I showed the group how to heat the plastic in a flame and then bend out and round the sharp edge that caused him pain. To do this I pressed the hot edge with large plastic spoon, holding it in the new position until it cooled.

After Walter David tried walking with the modified brace, the interpreter asked him in sign language how he liked them. He said now they didn’t hurt him, but that he still couldn’t walk as well as he could without them. I had warned him that might be the case. There’s a saying, “Plastic and spastic don’t mix.” But of course there are exceptions, so it was worth a try—and was a good learning experience for everyone.

To help prevent his feet from flopping over to the side when he walks, we decided to experiment with cardboard shoe inserts, with one side higher than the other.

In the final session Walter David showed off how much better he could walk with the help of the inserts. The group also made a cane for Walter David to walk on uneven ground. At the boy’s suggestion they added a leather arm band to the side to give him more stability— something like a Canadian crutch.

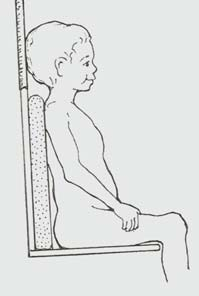

Walte David loved the workshop. He is thinking about becoming a rehabilitation worker when he grows up. Here he studies a copy of Disabled Village Children.

Diego Alejandro

For 23-year-old Diego there are no easy answers. I had my doubts as to whether there was anything that could be done or made fo him in our assistive technology workshop, but the local mediator was desperate to see if we could do anything to help him, and begged that we include him.

Unlike most of the people we visited in Medellín, Alejandro doesn’t live on the steep periphery, but rather in a tiny hut in an inner city neighborhood called La Independencia, on the banks of a trash-filled river that flows through the heart of the old city.

Diego is profoundly isolated by his multiple disabilities. He is blind, deaf, physically disabled, mentally stunted, and emotionally disturbed. His face has a desperate, long-suffering look. Diego often pokes and rubs his eyes, one of which is chronically inflamed. Representatives from both Liliane Fonds and from “Multi-impedidos”, a program that specializes in assisting children who are both deaf and blind, have searched for ways to help Alejandro, but with very limited success.

It is hard to know what level of intelligence or comprehension lies submerged beneath Diego’s angry, defensive, exterior. His only means of communication is through touch. Yet when his mother or others try to touch or hug him, often he strikes out or tries to bite them.

Diego spends his days sitting in a donated wheelchair, which he can’t move because the quarters are so cramped. He sits there hour after hour.

The group of mediators who visited Diego found that with help he could stand and even take steps, but in a crouched, very unbalanced way. After talking with his family, they decided to make him a standing frame—although some of us questioned whether he would tolerate being strapped into it. Back at the site of the workshop the mediators looked at different designs for standing frames in their books, and then drew a plan for one.

The next morning in the opening plenary of the workshop the group presented their concerns and ideas to those present. As they did so, a fascinating thing happened. Diego discovered that he was no longer confined to the cramped quarters of his home. At first hesitantly, and then with growing enthusiasm, he began to propel his wheelchair around the large central open space of the meeting room in which everyone was sitting in a circle around the edge. Like a bird suddenly escaped from its cage he wheeled freely in every direction.

When Diego was about to bump into people on the periphery of the big room, they would gently reach out and redirect his chair back toward the center. He had suddenly discovered a new and exciting way of communicating with people, realizing that they were facilitating his freedom while at the same time protecting him from mishap. It became a great game for him and his contorted face burst into happy laughter every time he nearly collided with someone and they amiably steered him on an open course. Everyone was delighted to see that agonized face suddenly so happy.

In the workshop, Diego’s group mediators worked hard cutting the pieces and building the standing frame. They added a table on the frame, and painted it attractively. But unfortunately they were unable to get Diego to stand in it in the final closing plenary.

Having had a taste of relative freedom that same morning, he was not about to be fettered into the frame. The local mediator promised to visit his home and help his mother see if they could convince him to accept it.

Whatever the final outcome with the standing frame, Diego’s free-wheeling adventure that morning in his wheelchair was perhaps the high point so far in his life, both in terms of unrestrained movement and helpful non- binding communication. The challenge for his family and the local mediators will be find ways to build on that.

Leónd Arío

The objective of the assistive technology work shops was to help disabled children—which according to the guidelines of Stichting Liliane Fonds can include young people up to age 25. At 32 years old, León Darío should not have qualified. But for him we made an exception.

It was León Darío who arrived, in his wheel chair, to pick me up at the airport when I arrived in Medellín. He impressed me as a very bright, enthusiastic young man. He works in the national office of Liliane Fonds in Medellín. Since he drives his own car—with adapted hand controls—he also runs a lot of errands and fills in as a chauffeur.

On the long drive down into the valley of Medellín, León Darío told me how he had become paraplegic. As a teenager he’d been walking down the street on an errand when suddenly he was struck in the spine, in a drive-by shooting. That turned his life upside down. He learned to get around in a wheel-chair—which in Medellín is a major challenge. And now he manages to live on his own in a small apartment. But what León Darío told me he most longed to do was to be able to stand and walk—be it with crutches—at least in certain situations. “Do you think there’s any chance?” he asked me eagerly.

That was the reason we decided to include León Darío in the workshop.

It was not an easy matter to get León Darío up the stairs to the 3rd floor of the convent where the workshop was held. He had to be carried. But living in Medellín, León Darío was used to such “human elevators,” and people were glad to help. In the final evaluation, however, everyone agreed on the importance of holding such workshops in wheelchair accessible quarters.

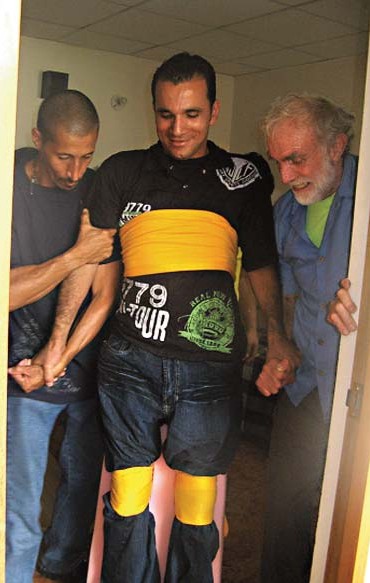

Before building a parapodium for León Darío, we had to make sure his hips and knees would straighten enough for him to stand. So his group of mediators had him lie down on a bed. Although he had a lot of spasticity, they found that with steady, slow pressure his knees and hips could be positioned almost straight—though not quite.

Next we stood him up to see if his feet would fit flat enough on the floor. Spasticity was again a problem, and this was complicated by beginning contractures, but with difficulty it was possible to place his feet in a fairly good position. With proper adjustments, standing on the parapodium might even help correct the contractures in his feet.

Then they took the measurements they needed. They made full-size paper templates of the pieces of the parapodium, which they traced onto sheets of plywood and then began cutting out the pieces. León Darío helped a local carpenter assemble the parapodium. They fastened on triangular supports to firm up the back board, and added sled-like runners under the base board.

One of the greatest challenges in making a parapodium is to make sure the backboard slants backwards just enough so that the person can stand upright in perfect equilibrium, without its tipping forward or backward.

At last the parapodium was ready for a provisional test. Because of León Darío’s spasticity it was hard putting him onto it, but at last they succeeded. Someone had brought a pair of crutches to see if León Darío could use them to move about on the parapodium, but to everyone’s disappointment they were way too short. So two of us played the role of “human crutches,” letting León Darío grasp our wrists.

To León Darío’s surprise, he found he could stand alone with the parapodium, without crutches or other supports, and with his hands free. “That means I can stand up in my house and use my hands to prepare meals, wash dishes, and do all sorts of things!” he said happily.

Everyone was thrilled to see León Darío standing and beginning to take steps. But no one was more excited than León Darío himself. While he realizes that in many circumstances he will still need to use his wheelchair, having the possibility to stand and move about upright will give him a new degree of freedom. If the parapodium works well for him, at a later time he can have a full-length body brace made with joints so that he can stand up and sit down. However that turns out, León Darío now feels he has more options.

Montería—The Provincial Capital

Compared to Medellín, Montería—provincial capital of the Department of Cordoba—looks more like a modest country town. Even in the city center, traffic is dominated by motorcycles, taxis and buses, with relatively few private cars.

Montería, like Medellín, has a dark reputation as a hot spot for crime and violence. For many years it was base for one of the most powerful paramilitary groups.

As with Medellín, the central part of Montería is surrounded by a mushrooming area of squatter settlements. The poorest and most peripheral neighborhoods are referred to as veredas, or pathways, because the myriad of tiny shacks are reachable only by narrow foot and motorcycle trails, rather than roads. In contrast to the precipitous favelasof Medellín, however, the terrain is relatively flat, and physically more accessible. Yet some of the veredas are said to be so dangerous that outsiders don’t dare set foot in them.

For the Montería workshop—as for the one in Medellín—over twice as many participants showed up as I had requested. On the day for hands-on construction of assistive devices, over 60 people were involved These included the nine disabled children being assisted, and their parents. The large number made the activity rather chaotic. But at least we were all in one very large open room, where there was ample space for the 9 busy groups. (Being all in one area made the sharing of tools and the overseeing the many activities much easier than in the Medellín workshop, where the different groups were widely scattered outdoors and indoors and on different floors.)

The Children of Montería

Luis

Luis is a 15-year-old boy with a condition called progressive myositis ossificans (also known as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva). He was born apparently normal, but little by little the soft tissue around many of his joints have turned into bone and the joints of his legs, backbcan’t sit.one and one arm have become frozen in deformed positions.

He spends most of the day lying awkwardly in an adjustable donated wheel- chair. He also spends time standing with the help of a stick. Although his hips are nearly frozen he manages to walk short distances, but because of the stiffness of his body he can’t sit.

The group of mediators who visited his home asked him what he most wanted to do, within his possibilities. He said he wished he could write and draw and use his hands, which he can’t do now because he can’t sit, and to stand he has to hold his pole with both hands. So he and the his group designed a unique table with an inclined support he could lean against while standing.

At the opening workshop plenary they presented their plans to everyone.

Luis was very shy about being exposed and talked about in front of such a large group. When people asked him to speak for himself he buried his face against his mother and began to sob. We all realized that we had not taken his feelings enough into account.

Eventually Luis lost some of his shyness and joined in, helping to sand some of the pieces. The completed standing table included a board for him to stand on so the table can’t scoot out from under him when he leans on it.

In the final presentation Luis took pride in showing the audience how he could stand and write at his new table. He smiled and spoke with confidence—a very different person from the one who had hidden his face and sobbed at the open plenary. The table will no doubt make a big difference in his ability to do things. But just as important is his new sense of self-esteem and readiness to face the world.

María

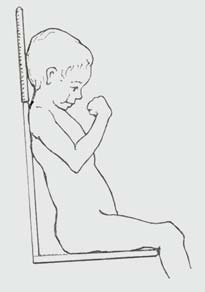

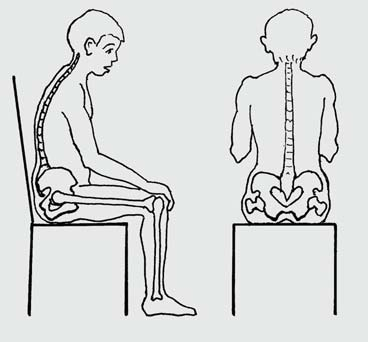

María is a bright six-year old girl with cerebral palsy who lives in a poor settlement on the outskirts of Montería. She has been given all kinds of costly and attractive assistive devices, which do not meet her needs. Her wheelchair was way too big, and the depth of the seat prevented her from sitting in a good, upright position. Her backwards lanting position tends to trigger the sudden spastic stiffening of her body. The wheel chair was equipped with a detachable headrest that was mounted in a poor position (see box on this page).

Seeing that the wheelchair didn’t work for the child, the local mediator had asked a local craftsperson to build a special wheeled seat for María. It was lovely and well upholstered, and fit the child better than the wheelchair. But it had no seatbelt, and when the little girl went into spastic extension she arched up and slid out of it.

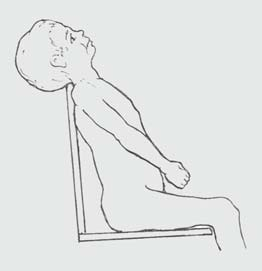

Because neither the of the above assistive devices worked for María, her mother usually sat her in a simple child’s rocking chair, which fit her better but had no footrests and no seatbelt. Because of spasticity María was constantly sliding out of it. Also, similar to the wheelchair, the chair-back pushed her head forward, so that in order to rest her neck, she kept her head turned to one side.

After visiting María and her mother in their home, a small group of mediators with the family designed ways to adapt both her wheeled seating aids to better meet her needs. The next morning at the opening plenary the group together with María’s mother, demonstrated the problems with the costly equipment she’d been given and showed everyone their designs for modifying the equipment to better meet María’s needs. Then they set about to modify the wheelchair. They built a padded insert that reduced the depth of the seat to let María sit at a better angle. They also scooped out indentations behind her head and under her buttock, allowing her to keep her head in a better position and to keep her body from slipping off the seat. A local carpenter helped adjust the footrest.

The Importance of the Positioning of Wheelchair Headrests

|

|

|

María’s wheelchair was equipped with a detachable headrest that was mounted in a poor position. Without the headrest María’s head tends to trust backward over the back of the wheelchair.

|

|

|

They adjusted the seatbelt to fit low and tight across her hips. But when they tried out the chair with María, they found problems with the depth and angle of the back, and with the placement of the seat belt and support straps. Unfortunately the group had already upholstered the seat before making all the needed changes—and time was running out.

In the last hour of the workshop, the group set about modifying María’s other wheeled seat. They added a soft cloth seatbelt, so that it would pull low and tight across the girl’s hips. They raised the footrest. And they cut indents for her knees into the front of the seat. These decreased the seat-depth so she could sit at 90 degrees with her butt against to backrest. The indentations also helped hold her spastic legs apart.

|

|

|

In the final presentation María sat much better in her wheelchair. But it was evident that it still needed improvements (which the local mediators promised to help the family complete).

However, the special wheeled seat was a great success. Both she and her mother were delighted.

Mauricio

Mauricio is a slender ten-year-old boy with spastic cerebral palsy who lives with his parents and two-year-old brother in a poor barrio of Montería. There was something haunting about him—an aura of loneliness and hunger for affection in the disabled boy’s eyes—that pulled my heartstrings from the first time I saw him. Although he can’t speak, he appears to understand quite a lot and is clearly sensitive to the family dynamics. During his first eight years of life his parents had showered him with their love and attention, as their only child. But since his unblemished, roly-poly baby brother was born two years ago, his parents have redirected most of their affection and expectations toward the younger child.

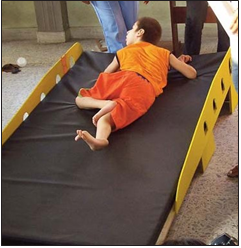

As a result, Mauricio currently gets little attention other than being fed, bathed, and changed. The doleful youngster spends most of his waking hours lying on a mattress on the floor, watching television.

The TV is kept on a high table. To watch it the boy lies on his belly and arches his back and head backward so far it is beginning to cause a deformity. When the visiting mediators asked his mother why she didn’t place the TV lower to the ground, so he could watch it more comfortably, she said she had to keep it out of reach of Mauricio’s mischievous baby brother.

Mauricio had been donated a wheelchair, but it was hidden away, unused. And with good reason. When the visiting mediators tried to sit Mauricio in the wheelchair, his spasticity stiffened and twisted his whole body so severely that they couldn’t put him a good position. Even when they finally managed to seat him, more or less, the seatbelt was attached too high to even begin to hold him in place.

Mauricio had also been giving orthopedic appliances: above the knee braces with a girdle. But given his extreme spasticity and lack of body control, the appliances wer totally inappropriate.

On their visit to Mauricio’s home, the mediators came to realize that the boy’s emotional needs were as great as his physical dysfunction. For example, in the evening when his father returned from work, the disabled boy’s face brightened into a huge, contorted smile. Clearly he had a lot of love for his father. But his father paid no attention to the affection-hungry boy. Instead, he picked up Mauricio’s plump, very spoiled little brother and began to hug and play with him dotingly, ignoring the disabled boy completely. Lying unnoticed on his mattress, Mauricio began to sob.

At first the visiting mediators were at a loss about to what to do for Mauricio. It seemed unlikely they could adapt his wheelchair so he could sit comfortably in it. And even if they partially succeeded, they were doubtful whether his parents would sit him in it. It appeared his mother and father had given up on him, and were resigned to just let him lie all day on the mattress.

Given the sad reality that Mauricio spent all day on his mattress watching TV, the mediators decided to try to make his prone position more comfortable for him, and less damaging to his neck and back. They designed an inclined bed for him to lie on, so he could watch the TV without straining his back and neck as much. In their design, they also included a large box-like container at the head the bed, for the TV. This way the TV could be placed lower to the ground, yet out of reach of the little brother.

The next morning at the plenary Mauricio’s group presented their plans to all the work- shop participants. After experimenting with Mauricio to find the best angle for the incline, they set about building and painting the sloping bed.

Mauricio seemed to enjoy all the attention he got in the workshop. For him, one of its high points, I think, was that his baby brother wasn’t there. He had his mother all to himself. The frenetic chaos on all sides seemed to rekindled the mother’s protective instincts, and she became closer and more loving with him. I think all the interest and concern directed toward her son may have helped her see him again less as burden and more as a person with his own kind of unique beauty.

|

|

|

Cerro Vidales

In both Medellín and Montería, the children we first visited in their homes and then assisted in the workshops lived in poor neighborhoods and squatter communities on the fringe of these cities. However, where I have most experience—and where I most enjoy working—is in the rural area: small villages, farmlands and forests where the natural and human environment still inter mingle. This being the case, long before departing for Colombia I’d asked the SLF national coordinators if I could have a chance to visit some of their rehabilitation activities in the rural area. So on completion of the workshop in Montería, the coordinators for Stichting Liliane Fonds (Sister Teresa and Marina) took me to a village area called Cerro Vidales, where the population is almost entirely indigenous.

In Cerro Vidales and the neighboring pueblos de indios most people are very poor—but there is a strong sense of community.

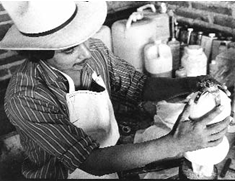

Families live off the land and often supplement their income through local crafts such as basketry and the weaving of sombreros. The rustic houses are made of poles—sometimes covered with mud—and have roofs thatched with palm leaves.

The people tend to live simply, growing most of their own food and collecting building materials and firewood off the land. They are very friendly.

In Vidales we stayed in a Catholic convent where the nuns assist the needy—often mak- ing home visits on motorcycle to outlying communities. Across the road from the convent Stichting Liliane Fonds helped with the building of a “Center for Attention for Disabled Persons.” The Center is very well organized. Records and photos of every child assisted—complete with diagnosis, goals, assistance provided, and progress achieved—is meticulously laid out in a loose leaf notebook. More detailed files on each child are kept in a file cabinet, color-coded according to the different types of disability.

The Center has a therapy room which includes, amongst other equipment, adjustable parallel bars. Unfortunately the bars were far too wide, and much too high—even at their lowest adjustment—for most of the disabled children needing to use them. (This is a common problem seen in many programs and countries.) The coordinators have agreed to adapt the bars for lower adjustments (simply by sawing off the tops of the fixed uprights) and to add new, closer bars for small children.

I was able to join with a number of mediators and concerned people, and visit some of the indigenous villages in and near Cerro Vidales. There we were able to make some assistive devices for children.

The Children of Cerro Vidales

Domingo

Domingo is an attentive eight-year-old boy with spina bifida. He has a pressure sore on his butt. It is now healing, but the scarring shows it was much bigger Not surprisingly, when we asked Domingo what he wanted most to be able to do, he said, “To walk!” We thought that he might be able to begin to walk with a parapodium, such as we’d made for León Darío in Medellín. So we needed to test if this might be possible. Since walking will depend largely on the boy having sufficient arm strength (to walk with crutches), we asked him to try to lift his body weight off the bench with his arms. With pride, the boy easily lifted himself into the air. His arms were strong from all the crawling he did. And his balance was excellent.

Next we tested Domingo for hip, knee, and foot contractures, which can be obstacles to walking. Unfortunately his knees didn’t straighten quite enough to use a parapodium. We taught him and his mother how to do stretching exercises. But that would take a long time. His legs were more likely to straighten using night splints that would gently stretch them for long periods of time. We decided to make the splints out of PVC tubing. A man brought some very thin walled PVC drainage tube, about 3 inches in diameter.

Because the thin plastic is so pliable, we decided to leave tabs projecting out from the brace to help hold it onto his leg. Then strips of rubber inner tube were bound above and below the knee, to provide a gentle but steady stretching action. Because the inner tube wraps tended to slip away from the knee, we decided to use a single piece of inner tube with a hole in the middle for the kneecap, and 4 long strips to encircle the leg above and below the knee.

Domingo said he could feel the brace stretching his knee, but that it didn’t hurt. We advised the boy and his mother to use it at night, but only for as long as it didn’t cause much discomfort. They could start with short periods, and gradually leave it on longer.

After seeing that the new night-splint design worked, we set about completing it—and making one for the other leg. To prevent the ends of the splint from cutting into the backs of his legs we needed to round them to avoid a sharp edge. To do this we heated the edge of the plastic with a candle and then bent the edge outwardly by pressing the hot plastic with a large spoon and holding it in the desired position until it cooled. The result was a gentle outward bend at each end of the splints.

Most important, everyone learned a new simple technique for helping solve a common problem. (Knee contractures often develop in children with cerebral palsy and other disabilities, and can be a big obstacle to walking.) I have previously used thicker, non flexible PVC pipes. But this was the first time I had experimented with this very thin, bendable PVC tubing, and it worked very well, easily opening wider to fit the child’s upper thigh, without need to heat and bend it.

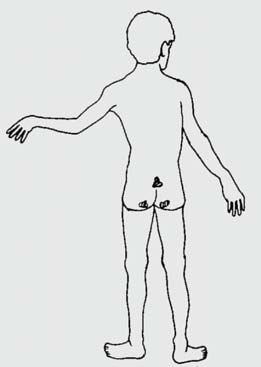

Pressure Sores from Inappropriate Seating

|

|

|

Midline Sores

|

|

|

** Sores on buttocks ** on either side of center (from sitting)

It finally dawned on us why Domingo has a pressure sore over his tailbone. It came from sitting in an oversized wheelchair—as well as in large hard-plastic chairs. In such big chairs his body leans backwards, putting pressure on the base of his spine. The risk of such sores is yet another reason for making sure disabled children have seating and wheelchairs adapted to their needs and size. We emphasized the importance of sitting on a soft cushion—and on chairs that would help Domingo sit upright.

César

[CAPTION[/CAPTION]

On the road outside the Rehabilitation Center we happened to meet a 6-year-old boy named César and his father, walking by. The local mediator explained that she had helped arrange surgery to correct the boy’s clubbed feet, two years before. But evidently the problem was not only in his feet, since the boy’s knees and feet still turned inward when he stood or walked. A doctor had recommended below the-knee leg braces, but since in-turning of his feet and knees appeared to originate mainly in the hips, is was doubtful the braces would help. Besides, it was unlikely that he would wear them, since he walked quite well without them.

So we decided to make a nighttime foot twister out of an old plastic 2-liter Coke bottle, to hold his feet angled outwardly at night. The hope is that this will gradually stretch the tight ligaments and tendons which turn his legs inward, thus helping him to stand and walk with his knees and feet in a more outwardly rotated position.

We inserted César’s feet through the hole in the plastic bottle. Although the thin plastic bent quite a bit, it held his feet widely open. César didn’t see seem to mind—and much preferred the idea of wearing this device while he slept than having to wear braces during the day. We advised him and his family to start using the device for short periods at night, and to remove it if it began to hurt. Little by little he should get used to it.

Orlieda

Orlieda is a 25 year old woman who lives in the Vereda de Salihal, near Cerro Vidales. She appears to have a slowly progressive form of muscular dystrophy. Muscles in her arms and legs began to grow weak in her early teens, and now she has trouble walking. Orlieda supplements her family’s income by carving wooden flowers, birds and animals, which she paints colorfully.

Orlieda’s legs are now so weak that she has trouble lifting them. Her right foot drags on the ground, causing her to trip and fall. We found her foot-dragging is due to her left leg being shorter than her right. We experiment ed a shoe lift—which we made with layers of cardboard—under her left shoe.

With her leg length equalized by the lift, Orlieda discovered she could walk without her right foot dragging so much. She felt more stable and self-confident, with less risk of falling. She will ask a cobbler to add a permanent lift to her shoe. This small modification may increase her ability to keep walking for additional months or years. Orlieda and her family were delighted.

Some Closing Thoughts

Why Do We See More Disabled Boys than Girls?

Of the children who attended our workshops, more than two thirds were boys. This was not due to preferential selection by the coordinators. Rather, there simply appears to be more disabled boys than girls. Many mediators wondered why, and no one had a very good answer.

One reason may be that certain genetic disabilities (like my own) occur only in males. But there may also be more ominous causes. Some of the mediators thought that perhaps they didn’t see as many of the disabled girls because the families kept them hidden away, and were less likely to seek assistance for them. In India, for example, many girl babies with impairments are simply left to die. Boy babies are better cared for and more likely to survive.

Building on What was Learned in the Colombia Workshops

Although it is hard to know to what extent those things that were learned in the workshop will be used on an ongoing basis, anecdotal evidence suggests that the benefits could be far reaching. The energy and pluck of many of the impoverished families there amazed me. The mothers of many of the children we visited were small and scrawny.

It seemed impossible that they would find means to carry their disabled child down the hundreds of steps and then find transport to bring them to our workshop. Yet the morning of the workshop, all eight disabled children, with their mother or father or sometimes both, showed up by 8:00 AM, and eagerly joined in the production of assistive devices for their children together with mediators of Stichting Liliane Fonds.

Hardship and the struggle to survive against crushing odds sometimes seem to bring out the best in people. Time and again I was amazed by the unstinting love and caring that parents bestowed on their disabled children. Day after day and year after year. Willingly. Gladly. Proudly.

Yet the extent of squalor and dire living conditions of the myriads of poor families crammed into makeshift huts on the steep slopes flanking the opulent urban center is deeply distressing. Human beings shouldn’t have to live in the kind of deprivation I witnessed!

Clearly, better use of technology is part of the solution. But if we are to give these children a fair chance, we have to also look at the social and political context in which they live. We must address the need to create a peaceful and sustainable world where land, opportunities, and power are distributed more equitably; where everyone’s basic needs and rights are met; where the strong no longer take advantage of the weak; and where we learn to live in harmonious balance, with one another and with the environment, for the common good of all.

In Memoriam: Marcelo Acevedo

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Marcelo Acevedo, who died in May of this year after a brief battle with a malignant brain tumor. Marcelo was a young village health worker with the Piaxtla Clinic in Ajoya, and later became a talented and caring orthotist and prosthetist, generously giving of himself to so many who came to PROJIMO for assistance. We’ll miss him.

Marcelo leaves a wife and four children, and it was his wish that they all complete school. HealthWrights has set up an account to help his wife, Chayo, get through this difficult time, and to help his kids realize all of their dream of completing school. Any assistance you can provide would be an enormous help. While one time contributions are certainly appreciated, what would be most helpful is a pledge over time. We can set up a recurring monthly charge to your bank account for this purpose. Please contact us for details.

Announcing Two New Publications

Slideshow CD: Workshop For and With Disabled Children in Columbia

The Colombian workshops depicted in this Newsletter are vividly captured in an exciting narrated full-length slide show, with many more examples, and more photos with each child.

This new resource is a great teaching/learning aid, with many original ideas. As with all our work, we put the disabled persons and their families at the center of the creative process.

Available as a CD for your PC (see insert), or as a streaming video online at http://healthwrights.org/slideshows/colombia/

Booklet: Health in Harmony

This colorful new 30 page booklet expands on our previous newsletter from the rainforests in Borneo, written by David Werner, and beautifully laid out by Jim Hunter.

Given the complex pressures of human survival and environmental preservation, this is an extremely timely report. See Insert to order.

End Matter

To help reduce costs and resource use, please subscribe to the Electronic Version of our Newsletter. We will notify you by email when you can download a complete copy of the newsletter. Write to newsletter@healthwrights.org.

| Board of Directors |

| Trude Bock |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing and Photos |

| Jim Hunter — Editing |

| Jason Weston — Design and Layout |

| Trude Bock — Proofing |

If we are to reach real peace in this world, and if we are to carry on real war against war, we shall have to begin with children.

—Mahatma Gandhi