Good News—And Not So Good News—From Bangladesh

Introduction

In February, 2012, I had the opportunity to attend the 40th Anniversary of Gonoshasthaya Kendra (The People’s Health Center) in Savar, Bangladesh. “GK,” as it is commonly called, grew out of the 1971 War of Liberation when the people of East Pakistan struggled for autonomy from West Pakistan. At that time Zafrullah Chowdhury, a young doctor who headed a medical brigade in the war, became concerned about the enormous unmet medical needs of his country’s impoverished majority, especially in the rural area. At the end of the war, Zafrullah and a few fellow doctors and nurses started a small “field hospital” in tents along the roadside in Savar, a village northwest of Dhaka. Over the next four decades, from this modest beginning has grown one of the largest and most transformative health and enablement programs in Bangladesh.

I have had the fortune to visit GK several times since its early years, and have witnessed the evolution of its many groundbreaking innovations. Zafrullah and I first met in the mid ‘70s in Japan, at an international seminar on “Health Care and Empowerment.” Neither of us had been aware of each other’s existence. But after we heard each other speak, each sought the other out, recognizing there was much in common in our grassroots efforts—in Asia and Latin America respectively—for the health and rights of the marginalized and oppressed.

Both Zafrullah and I realized early on that health is determined more by questions of human rights, equal opportunity, and adequate nutrition than by curative or preventive health services per se. The programs we started both focused on empowerment of the underdog. While I eventually ended up working extensively with the needs and inclusion of disabled persons, Zafrullah has become a tireless defender of the rights and equality of women—which he realizes is essential not only for their own well-being, but also for the well-being of children, men, and the whole community.

Empowerment of Women

The women-empowering initiatives of GK include:

Training of paramedics. The “paramedics” (relatively highly trained community health workers) mostly join the program as young village women. Training is largely hands on, “learning by doing.” After a couple of years of practice, the paramedic can specialize in such areas as physiotherapy, perinatal care and delivery, and ever-selective surgery, including tubal ligations. One village woman learned to competently perform such surgery, though she was illiterate.

Job training for equal opportunity. To open the way for more equality and income for women—especially poor single illiterate mothers (by far the most excluded and vulnerable group)—are taught skills and given jobs traditionally denied to women. These include carpentry, welding, and operation of machinery. To provide trainees with practice and then jobs, GK runs a number of productive workshops and small factories.

People’s pharmaceutical factory. Recognizing that the huge profits of big transnational drug companies (“Big Pharma”) place life-saving medicines out of reach of millions who most need them, in 1981 GK started its own pharmaceutical factory to make essential drugs and price them within reach of the poor. For its work force, GK Pharmaceuticals recruited mostly single illiterate village women. These were first taught literacy, basic math and hygiene/sanitation skills. Then they learned abilities necessary to run and operate the factory. The results have been outstanding, in large part because these women work with a dedication, responsibility, and loyalty far superior to the typical workforce.

Women on bikes. When GK began, in Bangladesh it was considered “improper” for women to ride bicycles. But GKs women paramedics often had to visit sick persons miles away, so GK began to teach them to ride bicycles. At first this caused a public scandal. One paramedic was forced off the road by an irate truck driver, and died. But in time people began to accept the female riders, and today one see girls and women riding bikes throughout Bangladesh.

Drivers training. To break the long-standing taboo against women driving, in the 1982 GK opened a Driver’s Training School for Women. Since then it has trained hundreds of women chauffeurs, for GK and for many NGOs and businesses. I rode several times through Dhaka with a GK woman driver, and was amazed at her ability to weave her way calmly though through the chaotic maze of cars, trucks, bicycles, rickshaws, motorcycles, and pushcarts. (It is said that some of these astounding drivers keep their nerves calmed down with ganja [marijuana]).

Schools that favor village girls. In Bangladesh many children of poor families—especially girls—don’t go to school. In part this is because their families need them to help with work, or to care for their younger siblings while the parents work. For girls, taboos also play a role, especially in conservative, male-dominated communities. This low level of schooling for girls has a number of consequences. It has long been recognized that “female education” is important in terms of women’s health and rights. It correlates with improved child survival, fewer pregnancies, and gains on the “Human Development Index” for the entire community. However, conventional schooling can also have a down side. In Bangladesh (as in much of the world) formal education has tended to be authoritarian and restrictive, emphasizing rote learning, completion, and unquestioning obedience.

To give more girls a chance to go to school, and to give disadvantaged children an education relevant to their needs, in 1976 GK began to set up its own “non-formal” schools in the poorest, most marginalized communities. I warmly remember my first visit to an early GK school. In the rustic building the children sat on straw mats on the floor. But here was a cheerful sense of camaraderie. Older children helped younger ones and quicker ones coached slower ones. For “homework,” after school in the evenings the school children were asked to teach what they’d learned that day to one or more village children who were unable to attend school. Thus the GK school fostered a strong sense of mutual help and reaching out to those in greater need.

Encouraging greater equality in more conservative communities.

One of GK’s aspirations, in terms of terms of women’s rights and opportunities, has been to have a gender-equality impact in the most conservative districts of the country, where men have unquestioned dominance and women are virtually their slaves. In such communities girls are customarily not permitted to go to school, and women’s illiteracy impedes their understanding their rights or inhibits their aspiring to greater equality. In many countries it has been shown that basic literacy for girls is one of the most effective ways of increasing their status and rights in the community—as well as their health and that of their children.

For this reason, GK seeks out these more conservative communities and offers to set up a school, free of fees, on condition that at least 50% of the pupils be girls and all the teachers be women.

Some conservative communities have agreed to these conditions. But others flatly refuse. In that case GK looks for other ways to win the community’s trust and cooperation.

Winning a Conservative Village’s Good Will

GK has found it difficult to introduce its equality-enhancing schools into some of the traditionally male-dominant communities, which tend to be wary of “outsiders.” The following example shows how GK won the good will of one such community. It was told to me by Andy Rutherford, a health activist who was my roommate at GK.

A huge cyclone hit Bangladesh in 1991, causing major disaster in the southern lowlands. GK was quick to respond. It reached distressed villages long before other aid agencies and even news reporters.

One of the hardest hit spots was Kutobia Island in the southeast. In those days Kutobia was reputedly one of the country’s most conservative places, and women were kept in a very subservient position. Nearly all were illiterate, since schooling was thought improper for girls. In the cyclone, a tidal surge 30 ft. high swept across the island. This left all wells and ponds salty and caused a potentially lethal shortage of fresh water.

GK at once sent a team of water engineers—most of them women—to Kutobia to help analyze the needs and drill new wells. But on arrival, the village leaders flatly refused GK’s help. “What can women know about solving our water needs?” they asked skeptically. But the GK team insisted that its women engineers were as skilled as men, and could help provide the urgently needed water. At last the village leaders—who were getting thirstier by the hour—decided to give them a chance. When the first wells drilled provided pure salt-free water, the incredulous leaders authorized them to continue. The worst of the crisis was resolved.

When the GK team returned to Kutobia two years later offering to start a school for the village children, again there were skeptical—especially when they learned that all teachers would be women and over half the students, girls. But after much debate the leaders finally came around. “We didn’t believe you could solve our water problem—and with women engineers—but you showed us you could. So we’ve decided to have a go with the school.” So the school was introduced, and more girls than boys began to attend. In Kutobia little by little women are gaining opportunities and rights.

At their peak, GK ran over 1600 village schools in 6 districts. But it proved very expensive to run the schools independently, since the Bangladesh Constitution—adopted in 1972—requires that primary schooling be completely free. Eighty percent of the funding for the schools came from foreign assistance. But with the current economic crisis in Europe, donations withered and over half the GK schools have now been turned over to the government.

To avoid reversals like this, GK tries to avoid dependency on outside funding and make most of its projects self-sufficient as soon as possible.

Bangladesh’s Unprecedented Improvement in Health

When Bangladesh won its independence from Pakistan in 1971, it was one of the poorest countries in the world, and had among the worst health statistics. But today, although Bangladesh still has a high level of poverty, the overall state of its people’s health has improved dramatically.

In 1985 the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored a study called “Good Health at Low Cost” to find out why certain poor countries had achieved unexpectedly levels of health, equivalent to those of countries with much higher per-capita income. The countries studied were Sri Lanka, Kerala State of India, Costa Rica, and China. These four nations had a number of characteristics in common that apparently contributed to their exceptionally high levels of health:

-

an overall structural commitment to equity;

-

universal primary education;

-

universal health coverage; and

-

an effort to assure that all children get enough to eat (a required minimum of calories).

In 2011 the Rockefeller Foundation underwrote a similar study, “Good Health at Low Cost—Revisited” looking at a new group of countries that have more recently achieved remarkably good health statistics despite their low economic status. The countries selected are Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Thailand, Tamil Nadu State in India, and—wonder of wonders—Bangladesh!

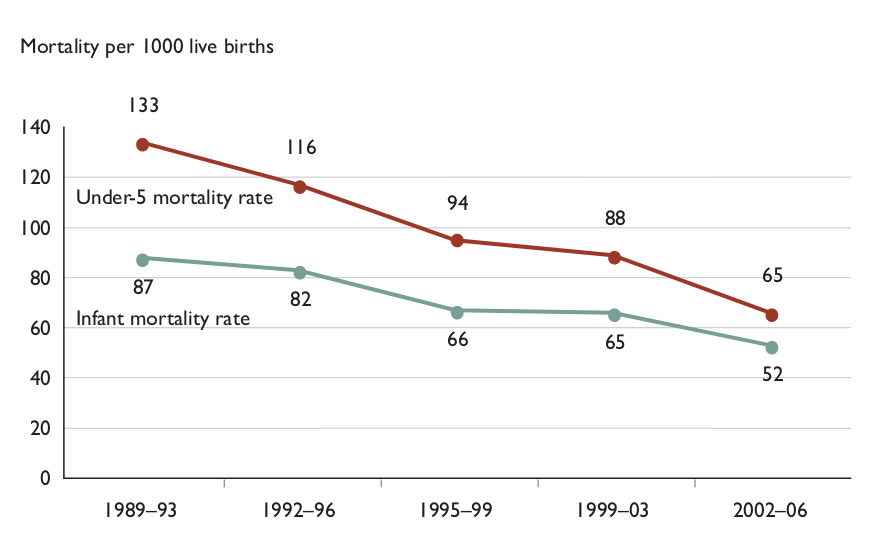

What factors or policies have led to these exceptional improvements in health in Bangladesh? At the time of its independence in 1971, Bangladesh was often dubbed the world’s most incorrigible “basket case” in terms of its crushing poverty and poor health. Maternal and infant mortality were extremely high and the majority of children undernourished. Even today—with a GDP (Gross Domestic Product per capita) of US$554—Bangladesh remains one of the world’s poorest nations. Half the population still lives on less than less than US $1.25 per day. Yet its health statistics are as good as or better than neighboring countries with much higher economic levels. According to the GHLC-Revisited study:

Compared to other countries in the region, Bangladesh has among the longest life expectancy for men and women, the lowest total fertility rate and the lowest infant, under 5 and maternal mortality rates.

In Bangladesh, maternal and Under-5 child mortality rates dropped nearly 80% in 40 years: from 243 deaths per 1000 live births in 1970 to 48 deaths per 1000 live births in 1910. And life expectancy rose by 27 years, from 42 in 1970 to 69 in 2010.

In trying to explain these exceptional improvements, the GHNC-Revisited study lists a number of interrelated contributing factors. These include:

-

A strong emphasis on education, especially that of girls. In 1971 less than 20% of girls attended school. Today 86% complete primary school and more than half of schoolchildren are girls.

-

Relatively strong government and non-government emphasis on health care, with attempts to reach the most vulnerable groups (poor, rural, and low caste, especially women and children) with basic preventive and curative and educative services. Immunization rates have reached 90%, and family planning has been widely promoted.

-

Economic measures and assistance programs—including microcredit loans directed at those who are most vulnerable, especially women.

The GHLC Study emphasizes the unusually strong role of large, idealistic Bangladeshi NGO’s (non govt. organizations) in supplementing and influencing government policy. It states: “NGOs grew and prospered and became the cutting edge for programme improvement. The government, albeit reluctantly, came to accept this and learn from NGOs.”

Among the in-country NGO’s that have most influenced government policy in health and rural development are Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK), BRAC (Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, and the Grameen Bank (microcredit program)

It is interesting to note that Bangladesh’s achievements have truly been “low cost” in terms of its total health expenditure: 3.4% of the GPD or US$12.00 per capita was spent on health in 2007. By comparison India spends 4.8% and Nepal 5.3% of GDP on health.

How is this “good health at low cost” possible? One explanation is that the vast majority of health services in Bangladesh are provided by non-titled volunteers or low paid community-level practitioners, rather than by licensed doctors, nurses, and other “titled” health professionals. Although Bangladesh does have a mix of “public-private” health services in which only 10% of curative care is provided publically, the vast majority of services are provided by so-called “non-qualified” (meaning untitled) health practitioners: village health workers, traditional birth attendants, Ayurvedic and Unani healers, and allopathic “doctors” without degrees. The biggest health advantage of these lay practitioners—apart from being part of the community and understanding local health-related beliefs and practices—is that, unlike the medical establishment, they typically serve the people at a price they can afford. And although the private for-profit medical sector in Bangladesh is rapidly expanding, most people still first seek the help of lay practitioners. And to compete with them, the private licensed medical workers have to keep their fees a little more affordable.

It has long been recognized that the disproportionately high cost of professional Western medical care and commercial pharmaceuticals has become a major obstacle to Health for All. In many countries, what low-income families spend on a medical emergency is the commonest cause of driving families into absolute destitution from which they never recover. The high cost of medical services and pharmaceuticals today have for many of the world’s people made health care a major threat to health. The fact that Bangladesh still has a vital network of local lay practitioners who “work first for the people not the money” may go a long way to explaining its “good health at no cost.”

Confronting Big Pharma

One area where GK has had a change-setting influence on national health policy is in its advocacy for low cost essential drugs. At first the Bangla government’s reaction to GK’s “People’s Pharmaceutical Factory” was quite negative, in line with the attacks from the transnational drug companies and the Bangladeshi Medical Association. Thugs were hired to fire-bomb the GK drug factory. Conservatives tried to frame Dr. Zafrullah for murder because he gave a “rabble rousing” talk at medical school about the exploitive practices of Big Pharma. When, weeks later, the students organized a peaceful protest, the police sent in to break it up became violent and some students resisted. Someone was killed. And Zafrullah—who was at the far end of the country at the time—was accused of homicide. The case dragged on for months. Finally charges were dropped, due in large part to a persistent outcry from international health activists.

Yet Zafrullah has also had supporters. With the shift in political winds, he was nominated to be the country’s new Minister of Health. But Dr. Zafrullah turned down the offer, stating that he could more effectively change the government’s health system from the outside. And indeed, under his constant urging and in accordance with WHO’s guidelines, Bangladesh passed laws authorizing generic production of essential drugs and outlawed import of over 200 unnecessary drugs pushed by Big Pharma. The transnational drug companies were outraged. Fearing other countries would follow suit, they lobbied Bangladesh to relax its restrictions. They threatened embargos. They suspended the supply of certain critically needed drugs. US-AID threatened to suspend its aid, and World Bank its loans, if Bangladesh didn’t repeal its restrictions of import of unnecessary and harmful drugs. But Bangladesh (to a large extent) held firm. This daring national stand against the exploits of Big Pharma is very likely a factor in Bangladesh’s progress toward “Good Health at Low Cost.”

Combating ‘Death from Diarrhea’

In Good Health at Low Cost—Revisited, another factor proffered to help explain Bangladesh’s sharp decline of child mortality is the country’s wide promotion of Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT). Begun by GK and BRAC, it was subsequently embraced by the national health system. However, the GHLC Study makes no mention of “politics of ORT” or the intense controversy over what type(s) of rehydration drink to promote. Nor did the GHNC scholars pick up on the fact that the bottom-up, empowering way ORT has been promoted in Bangladesh may help explain the dramatic decline in child mortality.

In most poor countries, diarrhea is still, next to pneumonia, one of the biggest causes of death of young children, especially those who are undernourished. Most of these children actually die of dehydration, or circulatory collapse from loosing so much fluid. Therefore, timely fluid replacement—or Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT)—given at home by mothers, siblings, or other caretakers, can save millions of lives.

But this “simple solution” has proved disturbingly complex—as David Sanders and I spell out in our book Questioning the Solution: the Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival. For all its praise as a key life-saving intervention in UNICEF’s “Child Survival Revolution”—Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) has at best been a two-edged sword: both saving and costing lives.

What ORT amounts to is the return of liquid lost: making sure that the fluid lost through diarrhea is steadily replaced with a palatable drink, or solution, containing needed salts and calories. Realizing such a drink’s life-saving potential, WHO and UNICEF in the 1982s launched a global campaign to promote ORT.

‘ORS Packets’ or ‘Home-Mix’?

Through the ‘80s and into the 90’s a heated debate ensued about which kind of oral rehydration drink was best: “ORS packets” (a factory produced product with precisely measured “Oral Rehydration Salts,” mainly glucose and NaCl), or “Home-mix” (a simple drink made at home using ordinary sugar—or, better, rice or whatever cereal or easily digestible carbohydrate or weaning gruel is on hand—with a bit of table salt.

Doctors, pharmacologists and politicians tended to favor ORS packets because the formula is (ideally) exact, highly controlled, and numbers of packets distributed can be counted and codified—providing a measure of usage rates in target-populations.

Community health workers and social activists tended to favor “home mix” because it enables mothers and child-minders to prepare the drink at home with local ingredients at low-cost, without having to depend on—or go a long way to get—a manufactured product that might be unavailable, or too costly.

WHO and UNICEF eventually opted for the “packets,” which, to mystify and medicalize them, they called “sachets”. They enlisted transnational drug companies to produce them by the millions. Designed to mix with one liter of water, ORS sachets would be made available to mothers at health posts and village shops.UNICEF’s early plan was to provide ORS packets to needy families free of cost. But then the World Bank stepped in with its mandate for cost recovery. Consequently in many countries poor families had to pay for the commercialized factory-produced product, when they could have simply prepared—at little or no cost—a “home drink” that would have worked as well (if sugar based) or better (if cereal based) than the standard ORS packets.

Today, in some countries, ORS packets are still made available free—but in many, not so. Back in the 1980s, the average price for one ORS sachet was around US 10 cents. That may seem cheap to health planners in Geneva. But to a poor family in Bangladesh—where in the ‘80s a daily wage was US 17 cents a day—spending 10 cents on an ORS packet could mean that for that day the whole family had to go hungry. Since underfed children are far more likely to die when they get diarrhea, the money a family spends on ORS packets can actually increase the chance of death from diarrhea, not only for the sick child but for all the young hungry children in the family.

Toward this inconvenient truth WHO has long turned a blind eye. WHO has been unacceptably slow to recommend cereal-based ORT—even though careful research (in Bangladesh and elsewhere) has established long ago that home-mix cereal-based ORT drinks are safer, cheaper, and more effective than sugar or glucose based drinks, including ORS packets. The fact that WHO’s Diarrheal Disease Control Program for years received a $2 million annual donation from Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceuticals, the world’s biggest manufacturer of ORS packets, may help explain WHO’s blind eye to better solutions. Such conflict of interest in public agencies has sadly cost millions of lives.

Dr. Zafrullah and I have discussed these “politics of diarrhea” for decades. From the first, our programs in Bangladesh and Mexico strongly promoted the home-mix solution over ORS packets. Likewise, both programs have used “discovery-based” teaching methods to help mothers and schoolchildren learn effective home management of diarrhea. In GK schools as in Mexico, the Child-to-Child approach is used where older children help younger ones learn health-protecting skills in a participatory hands-on way.

Teaching Schoolchildren to Save Infants’ Lives

On my recent trip to GK, I visited a GK school, where I watched a group of 8th graders teach a 2nd grade class about “watery stools.” It was exciting to see them using the idea of the “gourd baby,” which we popularized in Mexico, as part of the Child-to-Child approach. The gourd baby (shown in our book Helping Health Workers Learn) is marked to resemble a baby and has all the same holes a real baby has. Using the gourd baby, children make their own observations and draw their own conclusions. They pull the plug in its backside to give it diarrhea, and so discover different signs of dehydration (starting with the sinking fontanel). In GK, instead of gourd, they use a plastic bottle, but the process is much the same. I watched the older kids teach the younger ones to mix a home-made rehydration drink, and then taste it to make sure it’s no saltier than tears. The young health guides also emphasized the importance of hand washing before preparing the drink, thus stressing cleanliness to help prevent diarrhea.

Over the years, it has delighted me to see the gourd baby or its equivalent so widely used in many countries. I’ve often said (partly with tongue in cheek) that if, the gourd baby were used to help schoolchildren and mothers around the world learn to manage diarrhea effectively with a home-made drink, then the gourd baby could do more to lower child mortality than all the world’s doctors put together.

Amazingly, at least in Bangladesh, this hypothesis appears to be approaching reality. In GK—which teaches about ORT with the plastic-bottle baby in schools and on home visits by paramedics—the decline in death from diarrhea has been astounding. According to its records, from 2002 to 2008 the percentage child deaths from diarrhea dropped by 80%! In most poor communities around the world, almost half the deaths of young children are from pneumonia and diarrhea, in close to the same proportions. In Bangladesh diarrhea used number 1 killer of children. But in the GK villages this has radically changed. In 2008, while 45% of the child deaths were being caused by pneumonia, only 2.9% of deaths were from diarrhea! This huge drop in the diarrheal death rate goes a long way toward explaining the steep decline in the overall Under-5s mortality in GK’s area of coverage.

More encouraging still, the model of home management of diarrhea initiated by GK and scaled up by BRAC has now been adopted by the Bangladesh government and applied countrywide. As far as I know, Bangladesh is the only nation that strongly advocates home-mix ORT in favor of mass produced ORS packets. For 20 years the government has been teaching the home-mix method in the schools. And it has adapted the idea of the gourd-baby—but instead of a gourd or a plastic bottle, the Ministry of Education supplied a colorful “plastic-bag baby.” For teaching about dehydration, this plastic-bag baby has an additional advantage. Unlike the gourd or bottle babies, whose surface is rigid, the flexible surface of the plastic-bag baby allows children to learn the “pinch the skin” sign for dehydration.

The consistent promotion of home-mix ORT, taught in a participatory “learning-by-doing” way by government and NGOs, may help explain the nationwide unprecedented drop in child deaths from diarrhea. And this decline in diarrheal deaths may, in turn, help explain Bangladesh’s big decline in child mortality and emerging pattern of “good health at low cost.”

Underlying Determinants of Health

Of course, many factors in addition to gains in the rights for women and better treatment of diarrhea have contributed to the improved pattern of health in Bangladesh.

Preventive Measures

These include modest improvements in nutrition, and substantial improvements in potable water and sanitation, along with high rates of immunization (for most vaccines now over 90% coverage, even in rural areas).

Paramedics

Another key area where GK has substantially influenced national health policy is in the training and role of paramedics. Selected for their compassions and joy in helping others (rather than their grade point average) they learn wide range of curative, preventive, and health-promoting skills. In the GK program 600 paramedics work in the villages of 7 districts. In the 1970s, BRAC and other NGOs, following GK’s model, also started training paramedics, but on a much larger scale. Then, in 1977, the government initiated its Paramedics Training Institute. Today there are “hundreds of thousands” of paramedics throughout the country, even in the remotest villages. Trained in a much more comprehensive role than are government-sponsored “community health workers” in most developing countries, there is no doubt that these paramedics play a key role in Bangladesh’s achievement of “good health at low cost.”

Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs)

Another area where GK has made a major contribution to mother-and-child health is its training and support services for traditional birth attendants (TBAs). Where these TBAs are active, maternal and neonatal mortality has dropped to less than half the national average. In Bangladesh TBAs still deliver nearly 80% of babies. Therefore, upgrading their skills and providing back-up is of great importance. But unfortunately the Bangladesh government—following the guidelines of WHO—doesn’t work with or acknowledge the TBAs. Rather it trains “skilled midwives.” Yet these are relatively few in number and rarely go to out-of-the-way villages. Fortunately, however, paramedics cooperate closely with TBAs, especially those affiliated with non-government programs such as GK and BRAC.

Enormous Challenges Ahead

Bangladesh has made extraordinary improvements is health. The big question now is whether they can be sustained. While the gains have been impressive, many have been through piece-meal interventions, or innovations within the health system, rather than from addressing underlying causes—which turn on questions of equity, social justice and ecological viability. In Bangladesh many social determinants of health remain largely unaddressed: corruption is still rife, poverty and under-nutrition remain high, and the income gap between rich and poor continues to widen. To sustain the advances made so far, these underlying issues must be addressed. Adding to the challenge, many of the biggest threats to future health in Bangladesh come from environmental demise and power plays beyond the country’s control, at the global level.

Let’s look at some of these pending crises:

Population

Bangladesh is now the most heavily populated nation on earth. With nearly 160 million people (over half the population of the US) in a land half the size of California, its population density currently exceeds that of Japan or Singapore. Pollution, overcrowding and traffic (and traffic accidents) are horrendous. Forests, fisheries, and other national resources are being decimated. A range of measures have been taken to combat these devastating trends. They include reforestation, stocking of ponds and rivers with fish, and mandating the use of natural gas rather than gasoline and diesel for vehicle fuel in cities. But the human strain on the environment continues to escalate.

To promote maternal/child health and rein in population growth, the government has facilitated a nationwide family planning program, with free provision of contraceptives. Compared to neighboring countries, this has been relatively successful. In contrast to Pakistan, Bangladesh’s growth rate has been low. In 1971 Bangladesh’s population was around 75 million, while Pakistan’s was 45 million. By 2011 Bangladesh’s numbers has doubled to nearly 160 million, while Pakistan’s has quadrupled to 186 million. Birth rate in Bangladesh declined steadily for many years, but because of an interruption in the supply of contraceptives has recently risen somewhat. By 2002 women on the average, gave birth to 2.8 children, but the current average has risen to 3.1 children—not because couples want more children but because of donor countries like the United States axed family planning aid due to right-wing politics. As a result, the supply of contraceptives in Bangladesh (and elsewhere) ran low and the number of unwanted pregnancies increased. And of course so did the number of induced abortions, with an increase in suffering and death for countless women and babies.

Dr. Rezaul Haque, GK’s Director of Rural Health Training, told me why he thinks family planning is more popular in Bangladesh than other equally impoverished countries. “It’s our population density,” he suggested. “Here 80% of the people live by farming. They realize there’s no longer enough land to go around. If a couple has 6 children, none will inherit enough land to raise a family on. So today most couples don’t need to be persuaded to have fewer children. What they want is safe, reliable methods.” He added that many people, due to the shortage of contraception, are experimenting with the rhythm method, while others use traditional means of preventing or interrupting pregnancy—although the risks are considerable.

Given the failing state of the world today, with its environmental and economic crises and exhaustion of resource, Western leaders are very shortsighted not to make sure that all people who want to plan their families have safe, reliant means to do so. In terms of the health of individuals and the planet, few other simple measures are so cost effective and humane.

Shortage of Energy Supply

In terms of its steadily increasing need for energy, Bangladesh, like many other countries, is running on borrowed time. It has very limited undergoing oil, and is increasingly meeting its needs for fuel by exploiting its substantial reserves of natural gas. Natural gas is cleaner and has a smaller carbon footprint than oil and coal. But with the accelerating use of gas, the supply is fast running out. But rather than conserve what remains, the country has been selling natural gas to India. The country would do well to give priority to development of alternative energy. But as in most of the world, more immediate needs—and political game playing—take precedence.

Earthquakes

Geologically, Bangladesh is seismically active. The country is being squeezed between two massive plates—one under India, the other under China—which are gradually coming together. A major fault line that runs under Dhaka is the site of periodic earthquakes. The last major quake, 9 on the Richter Scale, struck Dhaka in 1895. In those days Dhaka was still a small town; the buildings were mostly single-story. Many were destroyed but loss of life was limited. Today, to the contrary, Dhaka is a teeming city of 20 million, with thousands of multi-story buildings that are not quake resistant. Many of these buildings, in violation of regulations, were built using poorly reinforced concrete with too low a ratio of cement to sand. When a major earthquake strikes, as it is bound to, the enormity of disaster will make the recent quake in Haiti look minor. Yet in Bangladesh little effort has been made to prepare for such a catastrophic event.

Global Warming and Rising Sea Level

There is little doubt that the biggest danger to the future well-being of Bangladesh is global warming and rising sea levels, Most of the country is barely above sea level and Dhaka, the capital city, is situated on a vast delta in the middle of the nation. Periodically huge cyclones, with perilous tidal surges, flood much of the farmland. As sea level inevitably rises due to climate change, most of the best farmland and most cities will be under water. This may begin in as little as 30 years.

How Bangladesh will cope with this sea change, together with the depletion of fossil fuels and the consequent social chaos that will arise from pandemic hunger, is hard to say.

Innovative Disability Programs in Savar

While visiting Gonoshasthaya Kendra I took the opportunity to visit two outstanding programs that work with disabled people.

Center for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed

The center is a program that I first visited in the early 80’s at its former, cramped quarters in a Dhaka hospital storeroom over 20 years ago. I was thrilled to see how much the program has expanded its outreach to new areas, with a broader range of activities. Started by British physiotherapist Valerie Taylor in 1979, the non-profit organization (NGO) continues to take a personalized, creative approach to serve some of the country’s neediest and most neglected people. The CRP adapts rehabilitation and assistive equipment not only to the unique needs and possibilities of the individual, but also to the local environment, customs, and living situation. For example, unique “low rider” wheelchairs are made for village women who cook, eat, and do a lot of household tasks at ground level. (Photos and details of these custom-made chairs are included in my book, Disabled Village Children.)

Because the CRP makes such extensive use of my books, the program welcomed me there with a crowd of people waiting at the gate. Inside the grounds, teams of spinal-cord-injured youth were enthusiastically playing basketball on an outdoor court. Nearby, disabled and non-disabled children were screaming with delight as they circled and swung in a colorful homemade Ferris wheel. I was glad to see that so many spinal-cord-injured participants were riding an adaptation of the Whirlwind Wheelchair, complete with puncture-proof Zimbabwe wheels, which was being made in the CRP workshop.

One feature I applaud at CRP is that disabled people play a leading role. The front desk is run by, disabled receptionists. This gives a welcoming feel, with a sense of inclusion and hope, to new arrivals.

|

|

|

CRP’s goal is to help the disabled people in its program to achieve a meaningful and productive re-entry into their communities. To prepare disabled people from the rural area for the conditions and challenges they will face on return to their villages, a “half-way community” with traditional mud huts has been built in the rehab center—complete with a vegetable garden and water pump. Here the skills of daily living can be relearned.

I was delighted, to see that the CRP, despite its growth, still has its very warm and human atmosphere and a sense of fun. It helps disabled people find ways to enjoy the present and look forward to the future with hope.

Center for Disability in Development

The center is a large, modern, well-run rehabilitation facility with branches in several districts. Like the CRP, for all its size and professional approach, it has a warm, participatory manner of relating to clients. During my first visit to CDD, I was moved by the way people welcomed me as an old, beloved friend. To my surprise, I was presented with a copy of the Bengali edition of Disabled Village Children, which CDD staff had devotedly translated themselves. An artist with a human touch had redrawn most of my illustrations to fit local features, dress and environment with feeling and sensitivity.

There were two features of the CDD that I especially appreciated:

First was the way staff, especially physical and occupational therapists, worked together with parents and family members (mostly mothers or grandmothers) as partners in the problem-solving process. Almost never did I see a therapist conducting exercises or activities singlehandedly with the child. Rather they were guiding family members in how to do it.

Second was the creative way the CDD made use of local, low cost materials (appropriate technology) to reduce costs and created assistive equipment that was suitable to the income and involvement of the families. They made highly imaginative and diverse use what has become known as “paper-based technology.” Using a combination of cardboard boxes and scrap paper, the staff had created a spectrum of stimulation toys, standing frames, balance boards and special seating, all colorfully painted or decorated, and adapted to the needs of particular children. In addition, CDD has been experimenting with low cost but high quality alternatives to the classic, very costly Western prosthetic components—such as knee-joints, for which they built trial models using molded plastic and other materials.

CDD has expanded and is addressing an even boarder need. It is eager to work more closely with health services and community based programs—which far too often don’t do much to facilitate the rehabilitation and inclusion of people with disabilities.

Toward a Closer Link Between CDD and GK

One morning as I had accompanied Dr. Haque, along with a GK paramedic, on her rounds to a small village, we visited a hut where there was a teenage boy who had lost a leg below the knee in a highway accident (a common cause of disability). Three years had passed and he still had no prosthesis. He walked awkwardly with a single homemade crutch. For lack of rehab or the most basic advice, the knee now had a serious flexion contracture. Since his family was enrolled in GK’s rural health insurance plan, I asked why he had been not been fitted him with an artificial limb. Somehow this hadn’t been considered as a possibility—partly because standard Western prosthetics tend to be outrageously expensive. Still, it seemed a shame for this young man living on a farm. A simple well-fitted limb could make a huge difference in his ability to support himself, and to his quality of life.

On visiting CDD that afternoon, I mentioned the young amputee I had seen that morning, and asked if there were any way that CDD could help him get a limb. The response was affirmative.

To make a long story short, it looks like this one young man has become the catalyst for a new level of cooperation between CDD and GK. CDD is eager. And both Dr. Haque Dr. Zafrullah from GK are open to having CDD conduct workshops help its paramedics learn more about disability, low cost interventions, and a range of ways to take action at the family and community level. If helping to foster closer collaboration between Gonoshasthaya Kendra and the CDD is the only outcome from my sojourn in Bangladesh, it will have been more than worth it.

Tampering with Nature and Tradition: the Return of Rickets

One of the more than 40 and community-oriented organizations that took part in GK’s 40th Anniversary confab, was a grassroots NGO that focuses on combating rickets—which has recently made a surprising upsurge in parts of Bangladesh. This NGO is headed by an intense young man with sequelae from polio who walks with crutches and runs a brace-making shop. His interest in rickets arose from the large number of children with deformed legs, whom he was fitting with orthopedic appliances.

Rickets—which leads to progressive bone deformities in children deficient in Vitamin D and/or calcium—had largely been considered a disease of the past. It was common in northern regions where many people, especially in winter, didn’t get enough sunshine (which produces natural Vitamin D in the skin). In northern, industrialized countries it has virtually disappeared, largely because of Vitamin D fortified milk. (The few cases of nutritional rickets that have occurred recently in the North are mostly in dark-skinned, exclusively breastfed babies of calcium deficient mothers.) In tropical regions where people tend to have more exposure to sunlight, rickets was historically far less common. It was relatively rare in Bangladesh—until “outbreaks” began to appear about 20 years ago. Since then rickets has increased, in some areas to near pandemic proportions. Today it is estimated that one in every 1000 Bangla children between age 1 and 17 has rickets.

The big question is, why? Opinions differ. Is it a shortage of calcium in the diet? Or of Vitamin D? Or both? Rickets is more prevalent in certain geographical areas. Over-farming, population density, and misuse of chemical fertilizers are all possible factors. The children affected are mostly those of poor families living on low-level farmland, whose traditional diet included a lot of small fish and some milk products. But in the course of “development,” diet changed due to several factors. One was a government policy to increase net food production, which called for turning grazing meadowland into rice paddy. Hence cattle and other milk-producing animals became scarce. Second was a radical decline in the numbers of small fish. As a flood-control measure (which mostly failed) engineers began to straighten and build embankments along the rivulets and brooks that webbed through the lowlands. This tampering with water courses apparently upset the aquatic ecological balance, decimation the population of small fish. As a result of these environmental interventions, local families no longer had cheap access to either milk or small fish: their customary sources of calcium. (The small fish provided calcium because people cooked and ate them, bones and all.) Deprived of these habitual sources of calcium, families switched children’s diet to lots of rice, supplemented with cheap junk foods. And the kids got rickets.

Air pollution is another possible factor worth investigating in the resurgence of rickets. Today in much of Bangladesh the air is darkly hazed with smoke dust, coming from the myriad of coal fired brick kilns, and from the high population density. Could it be that children are not getting enough sunlight? “Impossible!” say some health authorities. “True, in England during the Industrial Revolution, when unregulated burning of coal darkened the skies and blackened the buildings, there was a big outbreak of rickets—due to reduced exposure to sunlight. But Britain has long cold winters and rainy skies. Bangladesh has more than enough sunlight!” … But does it? People dwelling in hot sunny climates have evolved dark skin to prevent sunburn and skin cancer. But dark skin also obstructs sunlight’s production of Vitamin D. Furthermore, in blistering weather, mothers tend to shield their young children from the sun. Over generations a natural balance evolved so that children get as much sunshine and Vitamin D as they need. But when, in a single generation, the sky becomes perpetually hazed by smoke, perhaps that can lead to a shortage of Vitamin D—especially in very dark skinned children. In Bangladesh skin tone varies greatly. It might be interesting to study whether those children most prone to rickets have darker than average skin.

More study is clearly needed. In the meantime, children in rickets-prone areas need the assurance of diets with adequate calcium and Vitamin D, or at least appropriate supplements.

Whatever the case, dirty air is a big problem—as evidenced by respiratory infection. GK’s mortality statistics show that children’s deaths caused by pneumonia steadily increased over an 8-year period (from 2002 to 2008), and by 2008 reached almost 50%. This extraordinarily high proportion of death from pneumonia may be yet another indicator that air pollution has become a life and health-threatening problem.

Conclusion

The reemergence of an old disease like rickets is symptomatic of larger problems. The disruption of a healthy ecology, the crushing population density, the exhaustion of natural resources, and climate change with its rise in sea level, are all foreboding challenges for future health in Bangladesh. Like East Timor—which was the subject of our last newsletter—Bangladesh is like a canary in the mine. The fate of this endangered nation lies not in the hands of Bangladeshis alone, but rather in the hands of humanity as a whole. Even if we come to our senses soon and take action to drastically reduce our carbon footprint and greedy overconsumption of the world’s resources, global warming has already begun and will cause major calamity to humanity. But if we take daring steps now to radically change our dominant global model, from one of “growth for the few at all costs” to “equitable and sustainable balance for all,” perhaps humanity can subsist a few more millennia on this endangered planet. Ultimately we will sink or swim together.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |