A 7-Year-Old with Spina Bifida Discovers New Life: An Online Photo Documentary

This is the second HealthWrights Newsletter that is available only online, and is not in print. Cost of international mailing became too much. However, being “online only” gives a new degree of freedom. We can use more and bigger pictures, and more pages, at no added cost. So we present you, in this new format, a “slide show” or photo documentary: a series of photos with informative captions.

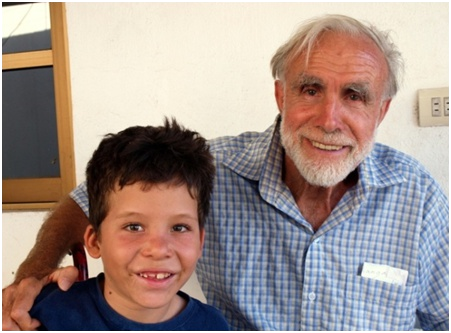

We tell the inspiring story of a disabled child and his rehabilitation at the PROJIMO Duranguito wheelchair workshop. Affiliated with HealthWrights, this small community-based program – run by disabled villagers – is located in the village of Duranguito, 70 kilometers north of Mazatlan, in Sinaloa, Mexico.

The team is dedicated to designing and building wheelchairs to meet the individual needs of disabled children. They evaluate each child individually, and build up to 300 custom-made wheelchairs and other assistive devices per year. In this case, however, the they have taken on responsibility for this child’s full range of rehab needs – both physical and social. For although the boy has a difficult background and an especially challenging disability, he has big dreams and lots of potential.

Click here to read and see more about PROJIMO Duranguito on this website.

This is a photo-story of the multifaceted rehabilitation of a 7-year-old child in rural Mexico. which is presently being realized in the village of Duranguito, state of Sinaloa, Mexico. This is happening under the guidance of PROJIMO Duranguito Skills Training and Work Program, a small struggling endeavor where disabled crafts-persons design and custom-make wheelchairs and other assistive equipment for children with special needs. Stichting Liliane Fonds, a charitable foundation in the Netherlands, is helping cover the costs on Miguel Angel’s rehabilitation. Local villagers, town leaders, and school children have also helped in a variety of ways.

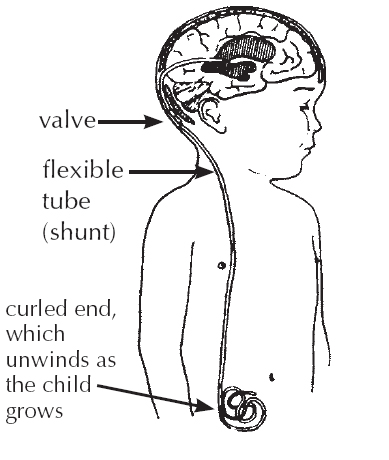

Miguel Angel Leon, was born with spina bifida, an embryonic malformation of the spinal cord that causes partial paralysis and reduced feeling in the lower body. As is often the case with spina bifida, the boy was also born with hydrocephalus, where build-up of fluid in the brain can enlarge the head and cause brain damage, unless early corrective measures are taken . With this difficult combination of special needs, and in the situation of poverty in which the child was born, the child’s prospects did not look good.

The boy’s mother who was 15 and single when she gave birth, lived in a very poor section of Las Flores, a small village along the highway north of Mazatlan. She lacked the resources to care adequately for her disabled infant. So his grandparents adopted and raised him, with a lot of love and care in spite of dire poverty and very little guidance or assistance.

Fortunately, however, soon after birth surgery was performed in a public hospital to cover the exposed ball of nerves on the child’s back, and a permanent tube or “shunt” was placed from his brain to his abdominal cavity, to drain off the excess fluid from the brain. Both surgeries, which can be quite risky, were successful.

|

|

|

|

Click here to read more about spina bifida, from David Werner’s book, Disabled Village Children.

When the rehabilitation team from Duranguito first discovered the boy, he and his aging grandparents were living in a decrepit hut, loaned to them in the small rural settlement of Las Flores. The hut had no running water, no electricity, and no bathroom – not even a latrine. This made caring for the child – who lacks normal urine and bowel control – a big challenge. Yet somehow they managed to keep him clean and relatively healthy. A bright, curious child, he had never had a chance to go to school. Though recently given a wheelchair, the sandy, rocky path to the distant school made it hard to get there. Before he had the wheelchair, the boy got around by crawling – or was carried.

Over the years, the child’s paralyzed feet had developed inflexible drop-foot deformities (equino-varus contractures). Although he could pull himself to standing and had some strength in his hips and knees, the foot and ankle contractures made walking impossible. Examining him, the Duranguito team thought that if the contractures could be corrected, he had a good chance of being able to walk with leg braces and crutches.

When the rehabilitation team from Duranguito first discovered the boy, he and his aging grandparents were living in a decrepit hut, loaned to them in the small rural settlement of Las Flores. The hut had no running water, no electricity, and no bathroom – not even a latrine. This made caring for the child – who lacks normal urine and bowel control – a big challenge. Yet somehow they managed to keep him clean and relatively healthy. A bright, curious child, he had never had a chance to go to school. Though recently given a wheelchair, the sandy, rocky path to the distant school made it hard to get there. Before he had the wheelchair, the boy got around by crawling – or was carried.

Because Miguel Angel’s mother was unable to care for child, his grandparents chose to adopt and raise him. They did so with a lot of love and care. Remarkably, they managed to keep him alive and fairly healthy, in spite of dire poverty and very little guidance or assistance.

Over the years, the child’s paralyzed feet had developed inflexible drop-foot deformities (equino-varus contractures). Although he could pull himself to standing and had some strength in his hips and knees, the foot and ankle contractures made walking impossible. Examining him, the Duranguito team thought that if the contractures could be corrected, he had a good chance of being able to walk with leg braces and crutches.

Considering all the needs and possibilities, the team invited the family to move to their village. Fortunately, a nice house was available on the grounds of the workshop, one of several houses constructed with the help of a generous Canadian, Peter Morris.

The house – complete with running water, electricity. and a bathroom adapted for wheelchairs – was well suited for the family. The rehab team and friendly village families helped equip the house with basic necessities, including simple furniture, a stove, a refrigerator, and cooking utensils.

The local community made the family feel very much at home. Some of them even donated food staples.

When we asked Miguel Angel what was his biggest hope, he eagerly said, “To walk!” … even if that meant with crutches and leg braces. But to improve his chances of walking, first the foot deformities needed to be corrected. And this would be a big challenge. The contractures were now so stiff that surgery might be required, However Raymundo, the workshop coordinator, hoped they could be corrected with “serial casting” – that is, by applying a series of plaster casts to gradually stretch the tight tendons and straighten his feet. (For this procedure see Disabled Village Children, chapter 59. Copy-paste this link into your web browser: http://hesperian.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/en_dvc_2009/en_dvc_2009_59.pdf.) In his early years at PROJIMO (in Ajoya) Raymundo – who is paraplegic – had learned the art of serial casting. But he knew the procedure can be risky, especially if there is reduced feeling in the lower extremities.

Here, to test for loss of feeling, Raymundo and Yasmín blindfold the boy and then gently prick his feet and legs with a sterilized needle. (To make this less unpleasant, they turn it into a game.) This test is essential because when feeling is reduced, extra care is needed to avoid pressure sores under the casts. When feeling is normal, pain is a warning sign. If pressure from the cast is too great, the child will complain and the plaster can be loosened or removed. But if it doesn’t hurt, this warning sign is missing, and risks are greater. Hence the casts must be put on with less pressure, be better padded, and be changed more often.

During the test, the boy tried his best to feel the pricks, and often he pretended that he felt them when he didn’t – even when Yasmin hadn’t actually touched him with the needle. Yet through repeated trials, it became clear he had almost no feeling in his feet, and very reduced feeling in his legs. In his buttocks feeling was also somewhat reduced.

This testing showed that great care would be needed when casting his feet. The casts would need to be put on with adequate padding and very limited pressure, and changed often to check for any redness. Even so, there was a substantial chance that sores might develop. Under such conditions, it was even more doubtful if the deformities could be corrected with casting, and surgical correction might be needed. But Miguel Angel dreaded the hospitalization and surgery. So the team and his family decided to give the serial casting a try.

Raymundo and Yasmín begin the casting. First they put on a soft “stockingnette” followed by a layer of cotton wool. Over this they roll on the plaster bandage, then hold the foot firmly in a slightly corrected position until the plaster dries.

To keep the boy’s casted feet elevated, the team improvised a horizontal foot support. They inserted a U-shaped metal rod into the side tubes of the wheelchair seat, and stretched a canvas cloth between the parallel rods.

The day following the first casting, Raymundo removes the plaster to check if the skin is healthy. To his relief, there is no signs of serious irritation or sores.

Raymundo changes or slightly modifies the angle of the casts every 3 to 4 days. This is more often than is typical in hospitals or orthopedic clinics. We have found that changing the casts frequently not only helps prevent or minimize sores, but usually results in faster correction of the contractures.

|

|

|

In preparation for beginning school, here Armando modifies the armrests of the boy’s wheelchair, so that a removable table can be fitted over them, secured with Velcro (self-sticking) tape.

The table fit well. But later, at Miguel Angel’s request, Armando made it narrower (less wide), so that the boy can propel his chair more easily when the table is in place.

|

|

|

Here Miguel Angel helps Carmen wash the dog. … The boy’s immersion into the life and activities of workshop opens up a whole new world to him. He comes to realize that disabled people can live full, productive lives. The fact that Carmen, Raymundo, and other members of the team are paraplegic, and as spinal-cord injured persons have essentially the same physically difficulties and challenges as does a child with spina bifida, makes the Duranguito program an excellent environment for helping the boy accept and learn to cope with his disability. And surely it helps the team members to empathize and instruct the boy – and treat him as an equal.

|

|

|

Miguel Angel loves to draw, and for his age has a lot of graphic ability. His grandfather, who also has an artistic bent, saved centavos to make sure his young ward always had a pad of paper and a pencil,) Here the boy colors some of his drawings, while his niece looks on.

The teachers and children in the primary school in the village of Duranguito have made Miguel Angel welcome and included. The rehab team helped facilitate this. They have established a good relationship with the school director, and with the help of his teacher have conducted Child-to-Child awareness raising activities with the school children.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With the teacher’s encouragement, the kids include Miguel Angel in their sports activities and play. They choose games in which he can play as an equal, without a significant handicap.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yasmín, wife of one of the wheelchair makers has taken charge of coordinating Miguel Angel’s schooling. Here, to help him catch up with his peers, she tutors him to read, using colorful wall-harts.

|

|

|

Grandpa was eager to help out – but his health was delicate and he tired easily. Because he had a chronic cough and was so underweight, the team suspected tuberculosis. They signed him up in a government health plan and took him to the city to be tested. The test for TB was positive. Now under proper medication, he is putting on weight and looks healthier. … Fortunately Miguel Angel has not contracted TB.

|

|

|

Miguel Angel’s aunt (on the right), who has also moved into the Duranguito house with her young daughter, likewise helps in the workshop. Here she, Yasmín and Carmin (foreground) use strips of emory paper to sand the rust off the metal tubes (electrical pipe) of the frames of the wheelchairs.

Miguel Angel – who now considers himself a member of the wheelchair-making team – is curious about how everything works. The workers are wonderful at explaining things and including him. Here Armando shows him how a drill press functions.

Having productive and friendly disabled persons as role models is a big plus. Miguel Angel has grown especially fond ofTomas, and often follows him in his wheelchair.

Tomas is especially good at involving the boy and finding ways he can help. The boy’s confidence and sense of self-worth have grown enormously.

Tomas is teaching Miguel Angel to lift his butt up off his wheelchair every few minutes, to prevent pressure sores, a wise preventive action for people who have reduced feeling in their backside.

|

|

|

The arrival of Miguel Angel’s extended family – mother, brothers and sisters, aunt and niece – at the house in Duranguito has given the boy a lot of enjoyment and camaraderie. Having been brought up alone by his grandparents, this is the first time he has actually lived with his mother and siblings. (Now his mother and siblings have moved away again, but his aunt and little niece are still there.)

For several weeks the serial casting of Miguel Angel’s feet progressed well, without problems, and the correction of contractures was advancing well. But it was a big challenge, as the boy was very active, and at play sometimes got the casts frayed or wet. Then, one day when Raymundo was changing the casts, he discovered that some pressure sores had formed on his right foot.

The sores didn’t hurt because the child had no feeling in his feet. Fortunately the sores were superficial, but casting had to be suspended until they healed.

|

|

|

So as not to lose the correction that had been gained, for the weeks that it took for the sores healed, the foot was stabilized in its improved position with a plastic brace.

The casting process, which has now continued for nearly 3 months, has proved remarkably successful. The child’s feet are now in a much more normal position.

Yasmín has consistently helped Raymundo. Here he guides her in doing the casting herself. Learning by doing has been the instructional pattern in the program.

Yasmín’s help is especially appreciated because Raymundo, who is paraplegic, now has to temporarily use a gurnney – or wheeled cot – instead of his wheelchair. This is because an old pressure sore on his butt opened up again, and he has to avoid sitting until it heals.

Because Miguel Angel, like Raymundo, also has reduced feeling below the level of his spinal cord damage, he too, has to take precautions to prevent pressure sores. To learn these skills, the spinal cord injured workers in the program are good role models – and teachers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Even without support, the corrected foot remains in a good position, and can easily be raised to a few degrees less than a right angle.

Apart from foot contractures, another obstacle to walking is that Miguel Angel has a bit of flexion contractures at the hips – meaning that his hips down don’t straighten completely, preventing his legs from bending backwards as far as they need to for walking. To help correct this, Yasmín is doing hip-stretching exercises with the boy lying with his legs over the edge of a table. She holds his butt down firmly to make sure the hip stretches rather than the back bending, while she gently applies prolonged upward pressure on the leg.

|

|

|

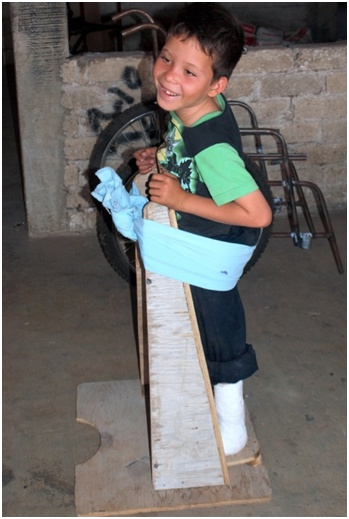

Even while his feet are still in casts, they are straight enough so the boy can practice standing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The frame not only helps him get used to standing, but the firm pelvic band helps to further straighten his hip contractures. It is important that the pelvic band be low across the buttocks, and not around the waist. That way it helps stretch the tight flexion contractures of his hips, and reduces sway-back when standing.

|

|

|

Miguel Angel has come a long way in his rehabilitation: physically, socially and psychologically. But he still has a long way to go. It remains to be seen how much bracing he will need to walk with crutches … and how well he adapts to the disturbing and often unfair world we live in, But the boy now has more self-confidence and greater hopes for the future, Above all, he has role models that he looks up to, classmates who include him, and friends in the village who cheer him on.

Stay tuned! We welcome you to come back to this page from time to time, as Miguel Angel’s open-ended rehabilitation continues to evolve.

End Matter

Help a Disabled Child Get a Custom-Designed Wheelchair

Help a disabled child in need get a custom-designed wheelchair made by the team of disabled crafts-persons in the PROJIMO Duranguito workshop.

To make a (tax deductable) donation through HealthWrights, click here.

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |