Child-to-Child Workshops: Making Schooling More Inclusive for Disabled Children and More Enabling for All Children

In February 2014 I, David Werner, visited Burkina Faso, West Africa, at the invitation of the Dutch NGO, Light for the World–the Netherlands. I was asked to exchange experiences in Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) and to facilitate workshops, using the Child-to-Child approach, to promote “educational inclusion.” The objective was to explore ways to make schooling more accessible, friendlier, and more helpful to children with disabilities—while at the same time making public education more relevant and empowering for all children.

|

|

|

Light for the World (LFTW) is a large, service-oriented non-government organization, in some ways similar to the German NGO, Cristoffel-Blinden Mission (CBM), with which it used to be affiliated. Like CBM, its original mission was to prevent blindness and restore sight–or light–to blind people in poor countries. Also like CBM, in recent years LFTW’s mission has expanded. It now embraces the philosophy and goals of “Community Based Rehabilitation,“with a broad focus on both the physical and the social needs of disabled children.

Light for the World currently has programs in many countries in Africa and Asia, and one in South America (Bolivia). In Burkina Faso it helps support seven Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) projects in different parts of the country. It cooperates closely with other programs, both non-government and government, in promoting the rights and habilitation of persons with disabilities. It places strong emphasis on the “educational inclusion” of disabled children, especially those children who are deaf or blind, because very few of these children are admitted to public schools, and those few who are have an extremely difficult time.

Plans for my visit to Burkina Faso had been percolating for several years—ever since I first met Lenie Hoegen at a workshop I led in India in 2005. At that time Lenie worked for the Liliane Foundation, under whose auspices the Indian workshop was organized. Lenie is now the Director of LFTW in Burkina Faso. Since early in 2013 Lenie and I had been planning the Burkina Workshop and hoped to work closely on its realization. But sadly, Lenie had a heart attack a week before it took place, and missed out. Thankfully she is recovering well, but we both regret her absence at the event.

In planning my visit to Burkina Faso, Lenie had been intrigued by a newsletter I wrote about a Child-to-Child workshop I led for the Education Ministry in Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, in 2007. Lenie wanted me to do something similar in Burkina Faso.

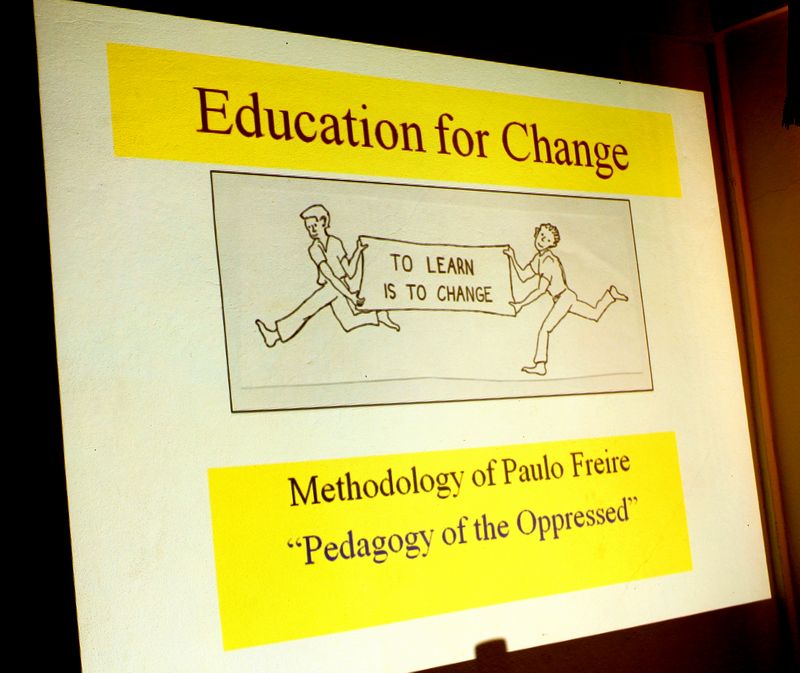

The Morelia Workshop was designed to address not only the needs for inclusion of disabled children, but also the health-related needs of all children–and to do so in an empowering, collaborative way. At that time the state of Michoacan had a progressive government committed to “educational reform.” It wanted to make schooling more relevant and inclusive, especially for children who have been traditionally marginalized, whether by poverty, ethnicity, or disability. Hence one of the goals of that Workshop was to help transform public education from an authoritarian system of social control, to a liberating environment of “education for change.” To this end, in the workshop we used the “liberating,” action-oriented methodology of the famed Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

With these change-making concepts in mind for our Child-to-Child Workshop in Burkina Faso, I was encouraged to introduce methods of “Discovery Based Learning” that would help children think for themselves, analyze their needs, and work together for the health, rights and inclusion of all.

In Burkina Faso this is a tall order–as I was soon to discover.In this impoverished African country with devastating inequities, to achieve a healthier, more inclusive social order, far-reaching structural change would be needed. Much of the population is increasingly ready for such change. But the power structure is militantly top-down, with social stratification deeply entrenched. Reinforcing this pecking order, schooling (modeled after the French colonial system) is also very top-down. Like schooling wherever the gap between the powerful and the powerless is great, it teaches students not to question but to obediently follow the rules.

The Situation in Burkina Faso Today

Burkina Faso-formerly Upper Volta-is a landlocked west-African country with 17 million people. It gained its independence from France in 1960. The UN says Burkina Faso is the world’s forth poorest country. It’s BNP per capita is US$600. With much of that income pocketed by a very wealthy minority, the poor majority struggle to survive on a pittance.

Telling facts about Burkina Faso:

-

The majority of the population (81%) live in the rural area, through subsistence farming.

-

There is a short rainy season and long period of drought.

-

Over half the people (80% of the disabled) live below the poverty line.

-

Over half of young children are undernourished.

-

Under-5 mortality rate is 147⁄1000 live births

-

Diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria are major killers, especially of undernourished children.

-

Life expectancy is 55.4 years.

-

Blindness rate is 1.4%, due mainly to cataract, trachoma, and until recently, onchocerciasis.

-

Illiteracy is 71%. UNDP says BF has the world’s lowest literacy, with girls much lower than boys.

|

|

|

Although Health is officially a top priority, public clinics and hospitals still charge too much for poor people to afford. Most people turn first to traditional healers, then go to the mission hospitals (mostly Catholic) or clinics sponsored by foreign NGOs. There are many such clinics, though not nearly enough, especially in remote areas.

In Burkina Faso the power structure has operated under a thin veil of election-based democracy, but in fact has been oppressive . The current President, Blaise Compaore, a military captain, took power through a coup in 1987, by overthrowing (with the help of France) the charismatic socialist leader, Thomas Sankara.

At first President Compaore made some progressive changes and won a degree of popular support. But as time passed he became more tyrannical and corrupt. He, and his family members, and cronies have amassed enormous wealth and live in palatial estates. (We drove by the President’s huge rural estate, with his own private zoo and personal army.) Although his popularity has waned, he still holds onto his power. Twice he changed the National Constitution to allow his reelection. And to assure it, has eliminated his competition by disappearances and arrests. He has now been in power for 26 years.

The next national election will be held next year (2015). The situation, though so far subdued, is tense. To be reelected once more, the President must once again change the Constitution. But this time, with the vast majority disillusioned and eager for change, people I talked with say that he probably won’t dare. By the same token, the President has cut back on the disappearances and arrests of his opponents.

In sum, Burkina Faso at present is percolating for change. But what sort of change will take place is uncertain. Will it be peaceful or violent? Will a popular government be elected that responds with fairness to the enormous needs of the destitute majority? Or will a new strong-man emerge who re- entrenches an exploitative elite? Will the people unite and stand up for their rights? Or will they submit to the same old domination and oppression they have been schooled to submissively accept?

Education as a Double-Edged Sword

The kind of schooling children receive has a lot to do with how they later respond to critical situations and the possibilities for change. Children who have been schooled to submissively obey authority and follow rules, however unkind or unfair, and to compete with their peers rather than to strive together for the common good, are unlikely to mobilize for positive change. But if children are educated in a way that encourages them to think for themselves, to make their own observation and draw their own conclusions, and then work together for the benefit of all, these children when they grow up are much more likely to become agents of positive change. They are more likely to see through the bribes and false promises of the potentates who beguile the naive to vote for them, only to further exploit them when they gain power.

Hence in societies with stark stratification between rich and poor, between the elite and the subjugated, school systems are designed to instill obedience to authority rather than commitment to equality and fundamental human rights. Suchschools are by design exclusive rather than inclusive. They separate the winners from the losers, the strong from the weak, the able from the disabled.

If standard schools are to become truly inclusive for all, far more will be required than simply making sure some teachers learn sign language and others Braille. Rather, it comes down to a question of redefining and redesigning the purpose and the methods of schooling. It is a question not so much of what we teach, but how we teach. It is a question of not of pushing ideas into the heads of children, but rather of pulling them out. A question of putting less emphasis on competition and more on cooperation, of everyone helping one another, of those who are quicker assisting those who are slower, of everybody finding a way forward together.

This kind of education for change is the rationale behind the so-call Inclusive Child-to-Child Workshop in Burkina Faso, as I envisioned it. These ideas are not just my own. Variations on the theme have been widely shared by iconoclastic educators the world round, from Rabindranath Tagore to J. Krishnamurti to Paulo Freire.

As will be seen in the presentation of the Workshop to follow, different people at the Workshop responded differently to some of the more iconoclastic learning methods I introduced to promote “inclusive education.” Some even questioned whether I was trying to kindle a socialist revolution.

Be that as it may, I think a lot of people–including many of the children involved–began to think about education and inclusion from a new and challenging perspective.

Burkina Faso, from the little I have learned about it and observed, is a country with a lot of needs and difficultiess, but in some ways a lot of strengths and potential. Its main strength appears to be in its people: the ordinary farming and working people. They struck me as having an intrinsic warmth, integrity, and sense of community. There was a basic friendliness and welcoming, especially outside the capital city, that made me feel comfortable and safe.

True, poverty in Burkina Faso is a big problem, and sometimes disabling or lethal. But with the poverty, like disability, the downside often has sometimes been its upside. In much of the rest of the world, the primary underlying cause of preventable chronic illness and death is over-consumption of sugar-loaded foods and drinks, linked with obesity But in Burkina Faso, most people can’t afford the sugary drinks and junk foods that are undermining the health even of (and especially of) the poor. In Burkina Faso, for the most part, only those above poverty level have a tendency to be overweight, and such persons are a relatively small minority. The very poor majority can’t afford such indulgence, and many of those I observed (admittedly not in the most remote areas of the country) looked surprisingly healthy.

Nevertheless, diseases like malaria and trachoma, as well as childhood diarrhea and pneumonia, still take a high toll. And for many, when people are sick, health services are either out of reach or ruinously expensive. Low wages, inadequate public services, and the stark concentration of wealth and power, unquestionably cause a lot of preventable suffering and death. Many people are ready for change. If schooling can be made more inclusive for those who are marginalized, and more empowering and egalitarian for all, perhaps the people will begin to collectively analyze their needs and join together to bring about the changes that can lead to greater health and inclusion for all.

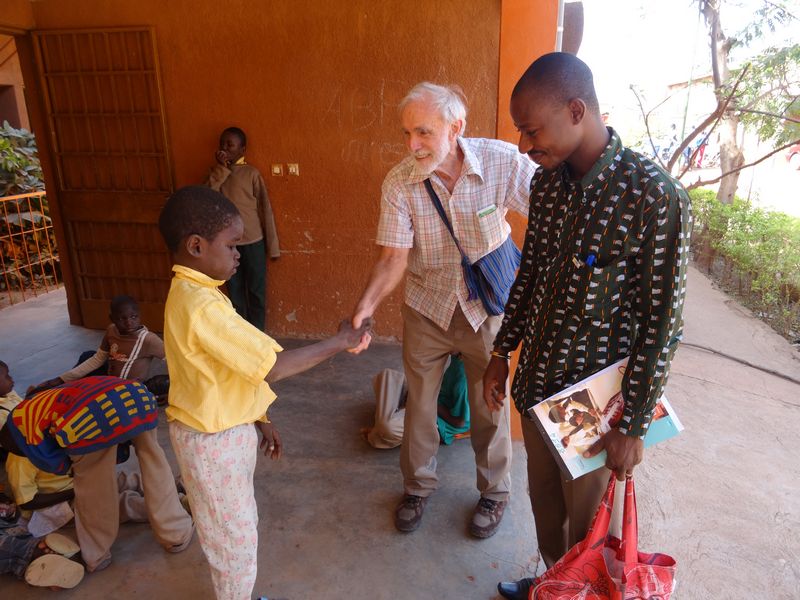

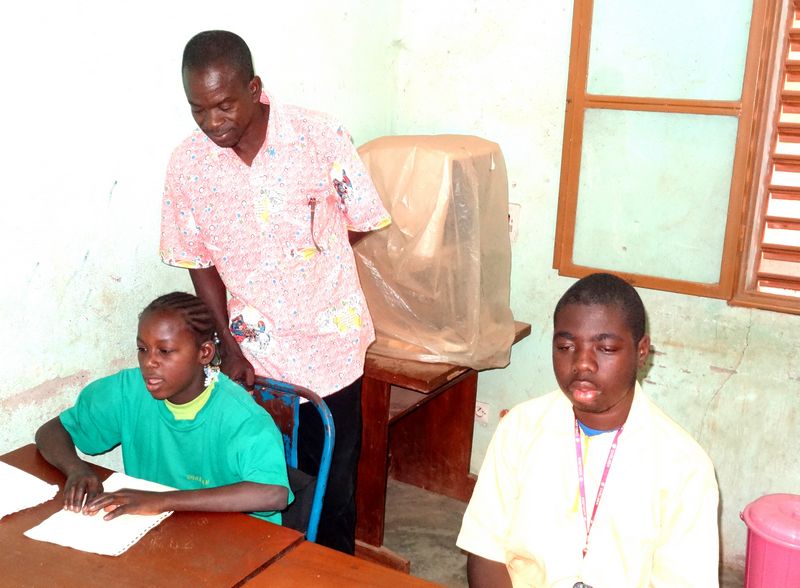

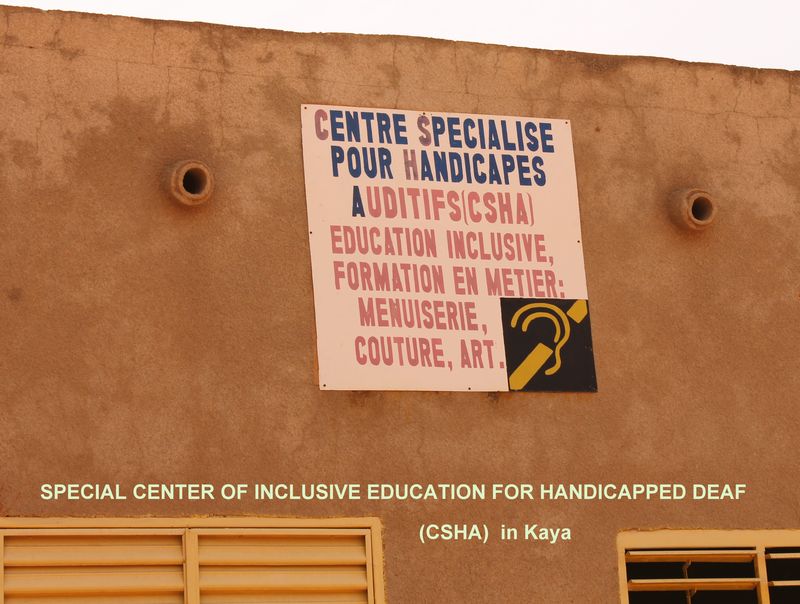

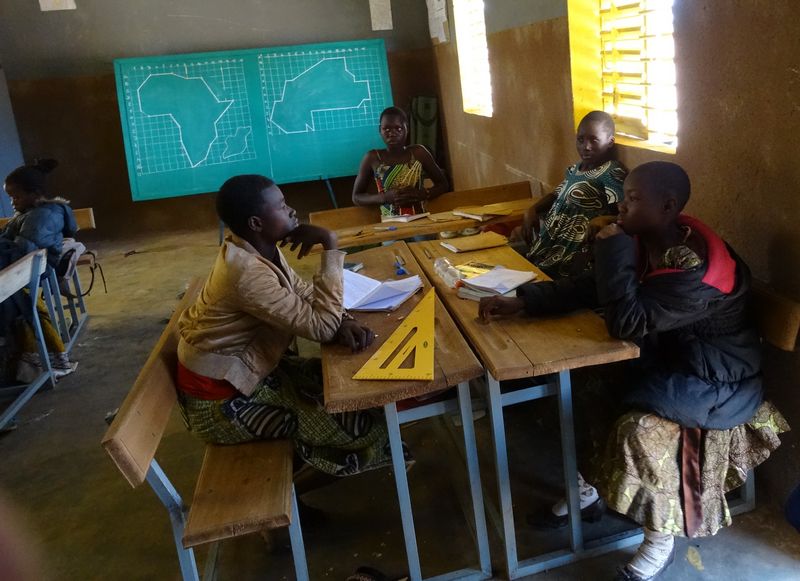

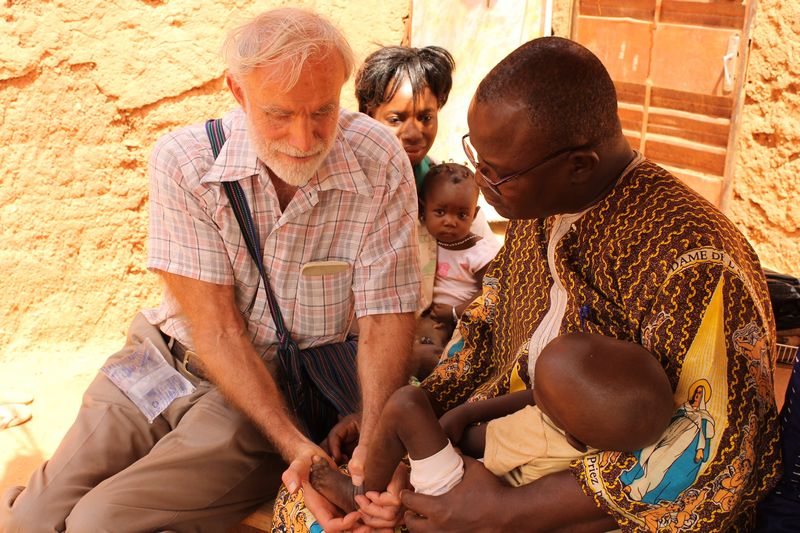

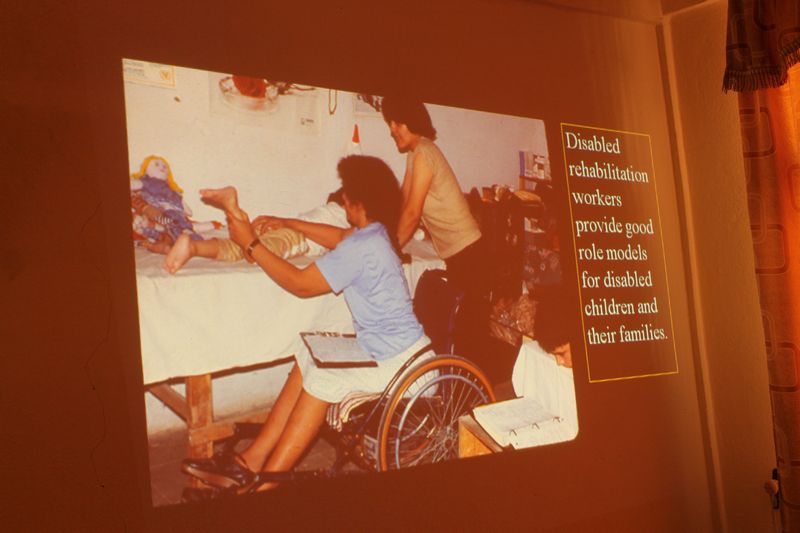

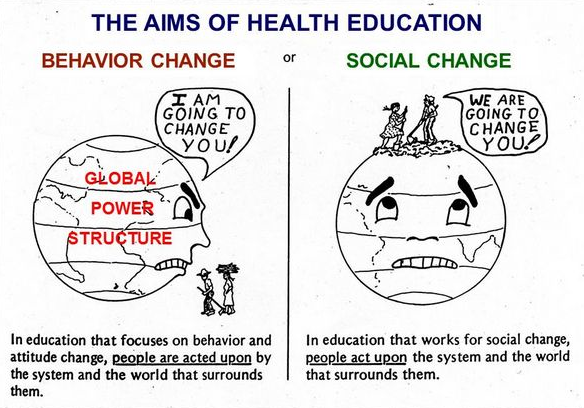

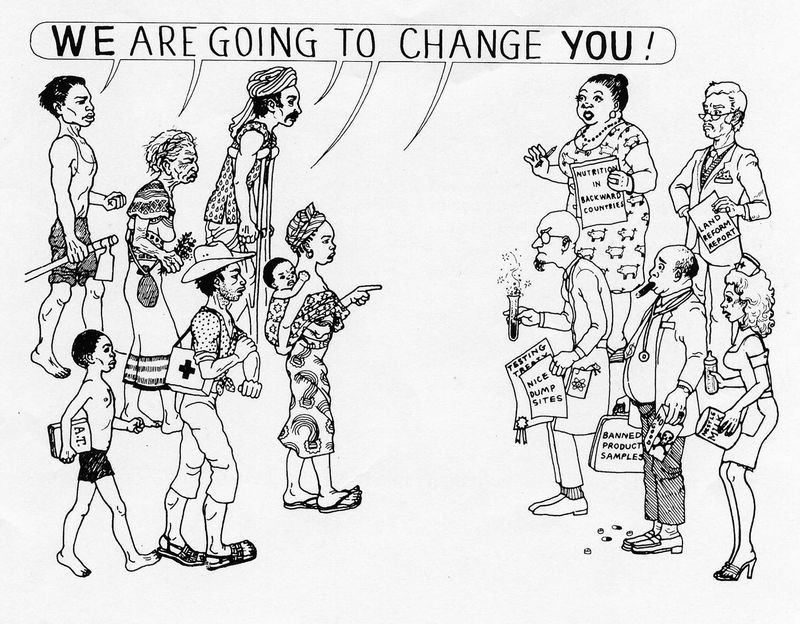

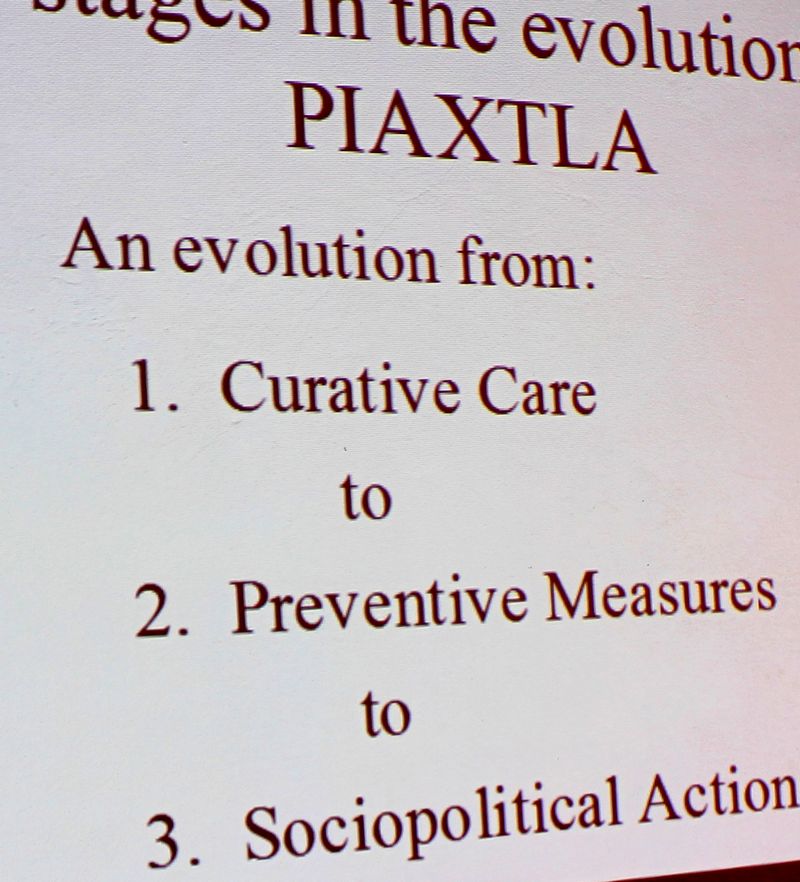

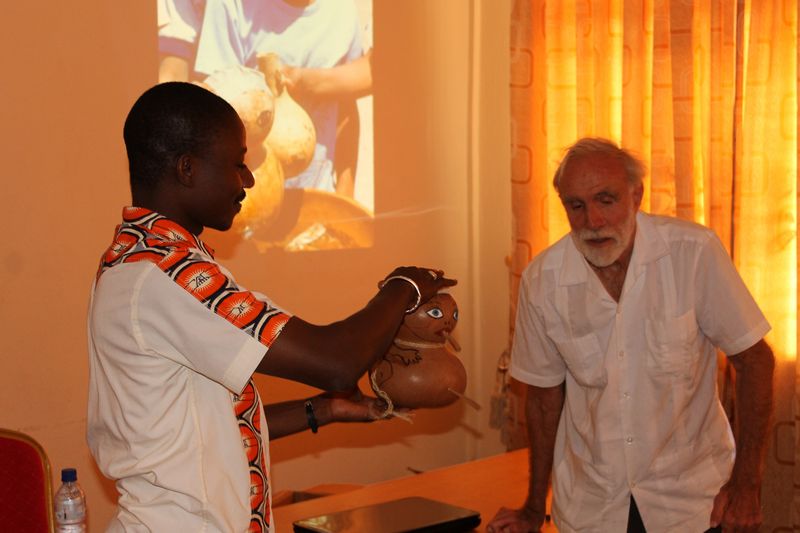

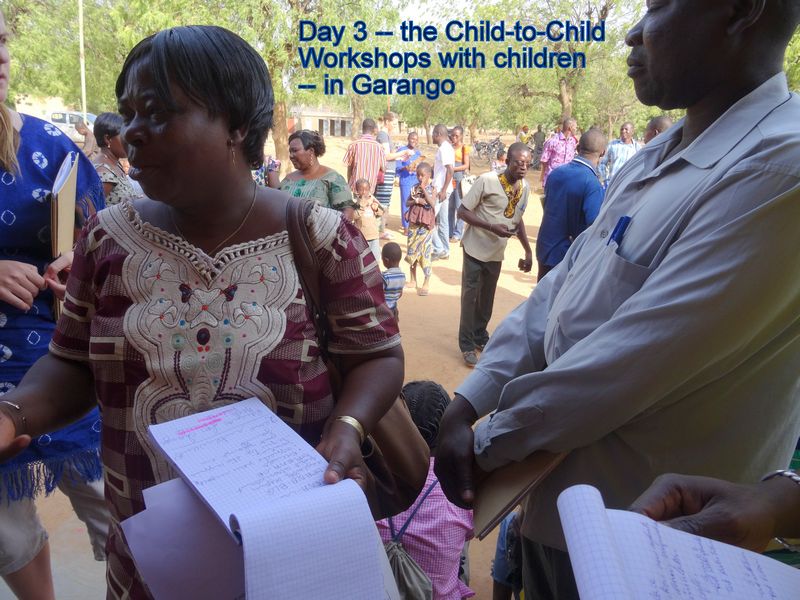

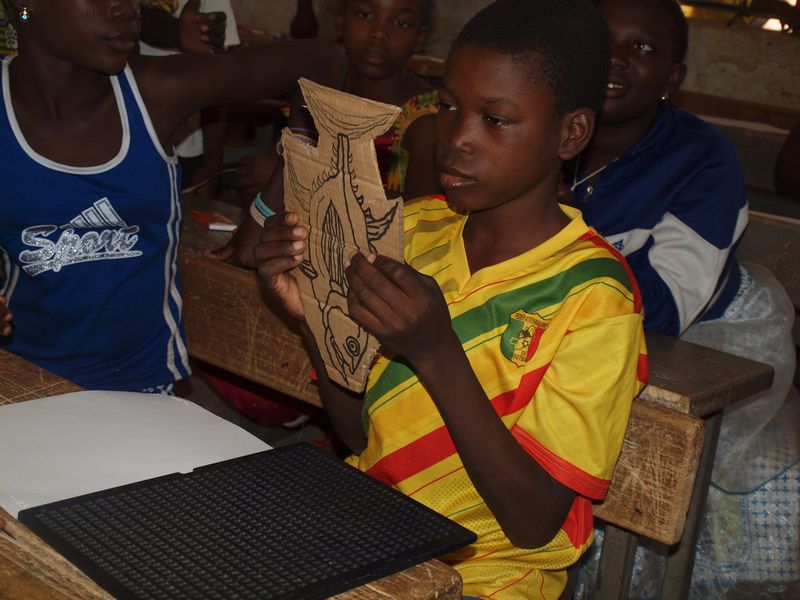

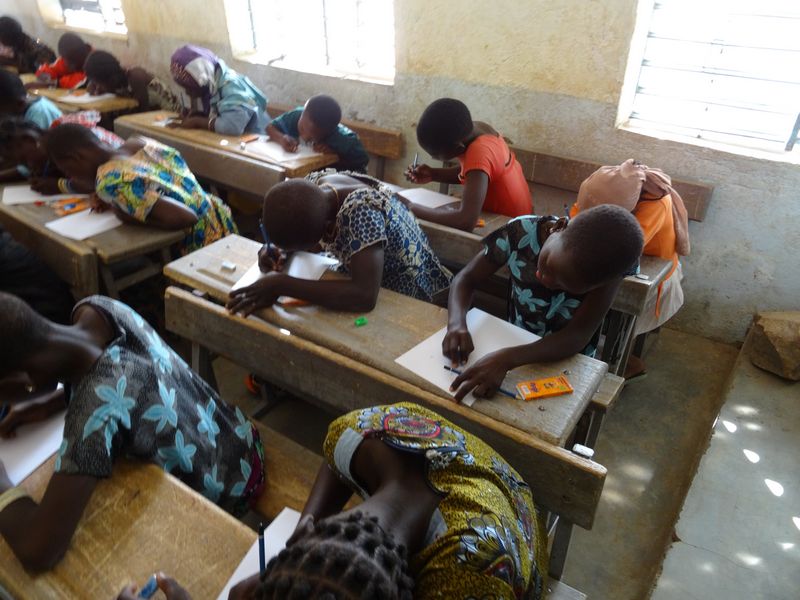

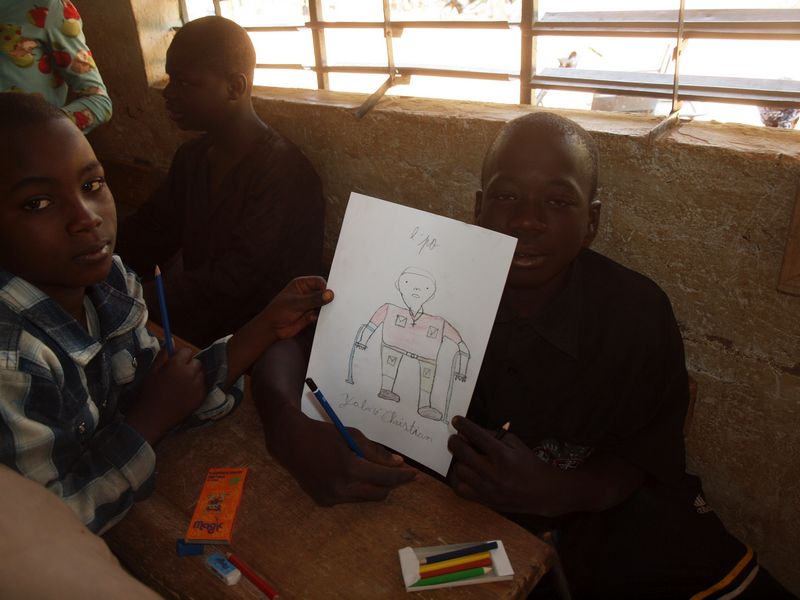

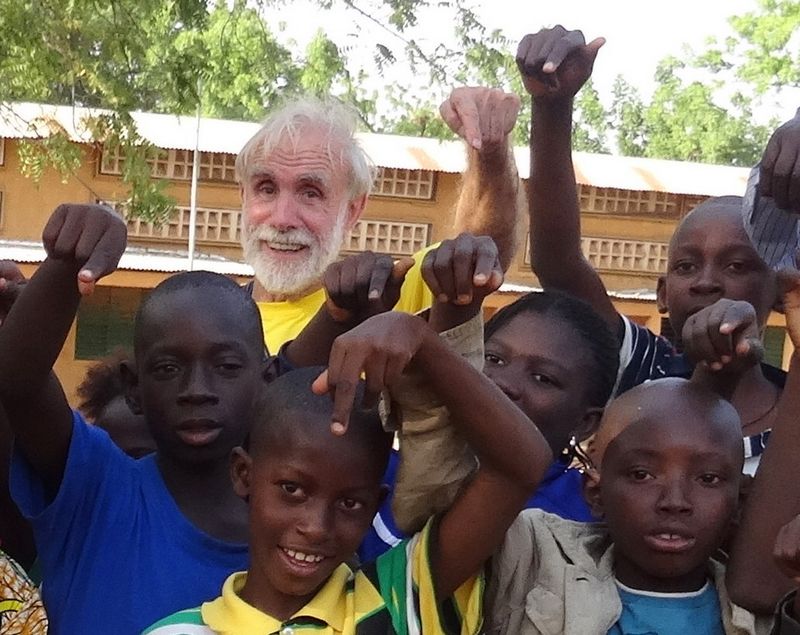

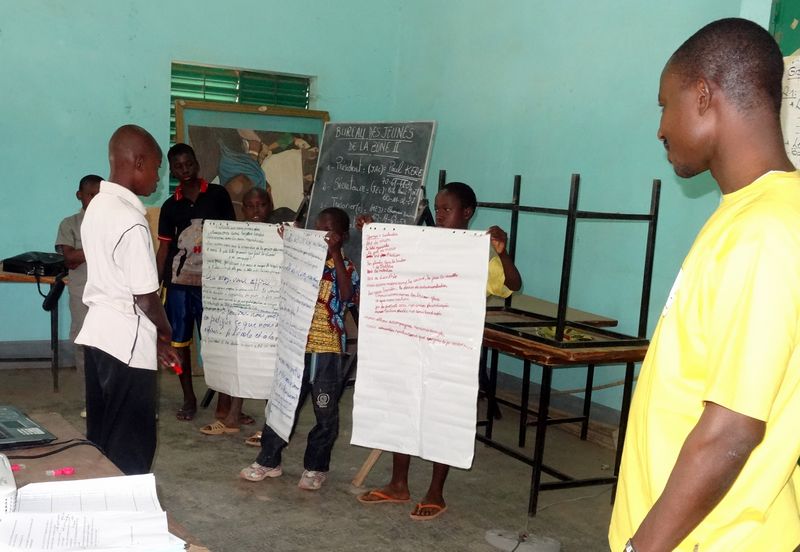

For further explanation and examples of the Child-to-Child approach and its use with disabled children, see the following books by David Werner, all accessible online in English and Spanish: The continuation of this newsletter on my sojourn in Burkino Faso is in the form of a photo-documentary. The first part covers my initial days in Burkina Faso, where the Light for the World staff took me to visit some of the activities and projects it supports in the capital city of Ouagadougou and neighboring areas. The second part covers the 4-day Workshop I facilitated in the towns of Temkodogo and Garango. The 4-day Workshop is arranged day by day: Day 1 and Day 2 are days of preparation in which participants planned, practiced, and prepared to facilitate “discovery-based-learning” activities for a mixed group of children. The participants–mostly potential”multipliers” of the Child-to-Child inclusive education methodology–included educators, teachers, special education instructors, CBR workers, representatives from the Ministry of Education, and staff from various NGOs. Day 3 is the key Child-to-Child event, realized with a mix of 50 non-disabled and disabled children. In two adjacent classrooms a pair of sessions are facilitated simultaneously by two groups of the adult workshop participants. Day 4 is a day of evaluation, in which everyone involved–including the children–take part. The School for Blind Youth In the capital city of Oagadougou was one of the first programs we visited. It is assisted by Light for the World (LFTW), the Dutch NGO that sponsored my workshop. Blind children attend this special school for the first six years, and then are mainstreamed into normal schools. However most of the public schools and their teachers are poorly prepared to accommodate the needs of the disabled children. Therefore Light for the World, collaborating with OCADES (Caritas in Burkina Faso) and other organizations, provides special training to teachers. In addition, these organizations attempt to raise awareness in general, since there are still a lot of fears and superstitions regarding people with disabilities. A blind child greets me and Philippe Compaore, Light for the World’s project assistant for inclusive education in Burkina Faso. Meeting the director of the school for blind children. One of the classrooms with blind children. In preparation for learning Braille, children arrange small pebbles in patterns on a grid. Many of the children use Braille to study their lessons. A copy machine for reproducing materials in Braille. The program produces learning material in Braille, not only for its own school, but for other schools that are beginning to mainstream blind students. The spirit of Child-to-Child comes naturally here. Older blind children often guide and teach younger ones. Children with limited vision are willing guides for those who are totally blind. Staff from the Light for the World took me to visit the town of Kaya, 200 km northeast of Oagadougou. Kaya is the base for one of the seven Community Based Rehabilitation projects assisted by LFTW. Here some of the staff and “CBR agents” of the Kaya Community Based Rehabilitation project pose with Elie Bagbila (on right) and me. Elie is Light for the World’s country representative. He has a more personal understanding of people with disabilities because he has a weak leg due to polio as a child. The Kaya CBR team welcomed me warmly. They presented me with a handmade leather briefcase and an artistic map of Africa. They call the French edition of Disabled Village Children their “bible.” I was happy to see that all the rehab programs I visited make good use of my book. Light for the World is currently planning to translate the companion book, Nothing About Us Without Us, into French, partly because it has examples of Child-to-Child activities for inclusion of disabled children. On the outskirts of Kaya is remarkable school and training center for deaf children and youth. Staff of the Kaya CBR center took us to visit this remarkable training center for deaf children, with which LFTW and the CBR program collaborate. The CSHA School is “inclusive” in that it has both deaf and non-deaf pupils: 160 in all. The youngsters appear to enjoy it and get along well. The Center provides scholarships to the deaf children from poor families. Over half of the children attending the school are deaf. The daughter of the CSHA’s founder is among the hearing children who attend the school. Because the quality of teaching is much better than in the regular schools, plenty of non-disabled children attend. This teacher, who is deaf, attended the CSHA school as a boy, and now teaches here. He is a great role model for the children, whom he treats with friendly respect. Classes are small, with lots of individual attention, whereas in the standard schools classrooms have up to 70 pupils. The CSHA teaches the children to use sign language, and tries to mainstream them into regular schools as soon as possible. But most schools and teachers are poorly equipped to include them. Light for the World, which helps sponsor CSHA, is collaborating to train teachers in normal schools to better meet the needs of deaf, blind, and other disabled children. For the deaf children, their hands are their tongues. This large, high quality rehabilitation and surgical center in Kaya was set up by a Swiss NGO. Although it is run and staffed by local doctors and therapists, a team of orthopedic surgeons and other specialists fly in from Switzerland four to five times a year. Services for the poor are virtually free. Special facilities are provided so that relatives can stay there with their disabled family member for as long as is needed. The Morija Center provides referral services for the Kaya Community Based Rehabilitation project, as well as the other CBR projects supported by Light for the World and OCADES (Caritas, the Catholic assistance program). The therapy room of the Morija Center is well equipped with modern equipment, yet has a friendly, down-to-earth atmosphere. Here a local physiotherapist teaches a brain-injured man’s wife to help with his exercises. The CBR agents of the project near Kaya took me to visit the homes of two disabled children. This child has epilepsy and developmental delay. Epilepsy can be a major stigma, since many people believe the person with fits is possessed by evil spirits. Dispelling these beliefs is a big challenge for the CBR agents. Here Elie Bagbila, the country representative for Light for the World in Burkina Faso, greets a disabled child in the family home, near Kaya. The little boy has cerebral palsy with a lot of spasticity. This special seat, brought from Holland and made of molded plastic, doesn’t work well for the spastic boy, who constantly slips forward. We tried positioning the child better and holding him in place with the attached seatbelt. But the belt was attached so high that with his spasms the child soon thrusted forward under it. Although the child’s spastic feet pushed stiffly downward, I found that by bending his knee, his foot could be slowly raised to less than 90 degrees. We suggested that his mother do these exercises regularly, to prevent contractures that could reduce later possibilities for walking. As is common in CBR programs in many countries, much more attention tends to be placed on children’s social needs than physical needs, and often the assistive equipment provided is unsatisfactory. An example is this girl’s oversized wheelchair. Notice the distance between her feet and the footrests! Also, the chair is so wide, it makes it harder for her to push it herself, perpetuating her dependency on others. Staff from the Light for the World and I visited officials from the mayor’s office, the Ministry of Education, and influential NGOs, as well as the priest of the local Diocese. These meetings were critical because one of our objectives was to promote the inclusion of the disabled in the public schools, as well as to help make schooling more relevant and empowering for ALL children. Our goal was that the methods of awareness raising, inclusion and “education for change” would not only be adopted by the educators and children in the workshops, but would progressively be “scaled up” throughout the country, and beyond. For this reason it was thought that gaining the good will and involvement of planners and decision makers was important. Here representatives of the Ministry of Education pose for a photo with staff of Light for the World and David Werner. Philippe Compaore, Light for the World’s Project Assistant for Inclusive Education in Burkina Faso, discusses the purpose of the workshop with the regional director of the Department of Education. The Director became so interested in the Child-to-Child approach that she attended and participated in our workshop herself. She plans to integrate some of the discovery-based activities, both for health education and inclusion, into the school curriculum. In our preliminary visit to the Department of Education we were joined by my interpreter, Sanogo Hamadou (center) and Marieke Boersma, from Holland, who is the international advisor and CBR trainer for Light for the World in Africa. The first day of the Workshop focused mainly on different approaches to Community Based Rehabilitation, and how the CBR concept has evolved over the years. Here Marieke, who came all the way from her base in Ethiopia, joins me in the opening session of the workshop in Tenkodogo. Enthusiastic about the workshop, she plans to introduce some of the activities into the programs she councils in other countries, especially in South Sudan where children’ health and disability needs are exceptionally dire. My interpreter (sitting across from me) did a good job translating my English into French. But with the translation, everything took more than twice as long, and I couldn’t cover all the themes I’d hoped to. Participants in the workshop were persons chosen to become “multipliers” of the inclusive Child-to-Child methodology. The expectation is that they will introduce the approach in schools and communities, first locally as a pilot program, and then throughout the country. The participants included educators, officials from the Health Ministry, school teachers, special educators, Community Based Rehab personnel, and representatives from various NGOs such as Christoffel BlindenMission, Stichting Liliane Fonds, OCADES (Caritas), and others. During the first day of the workshop I presented slides of PROJIMO, the village-based rehabilitation program I helped start over 30 years ago in rural Mexico. I emphasized the importance of leadership in such programs by disabled persons themselves. (The CBR programs we visited in Burkina Faso–like many elsewhere–have relatively few disabled persons in their ranks. CBR programs need to put higher priority on “inclusiveness” within their own organizations.) Burkina Faso, for all the friendliness and good will of its people, has a very top-down, authoritarian government and highly inequitable distribution of wealth and power, which goes a long ways toward explaining the hardships, hunger and handicaps of a vast number of its people. Early in the workshop therefore, I felt it was important to stress the need to prepare young people to become “agents of change.” I pointed out that in Latin America, Child-to-Child activities are often facilitated using the empowering, discovery-based methodology of the iconoclastic Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, author of “Pedagogy of the Oppressed.” Freire compared conventional education–which is in large part obedience training designed to perpetuate the inequities of the status quo—with “liberating education” or “education for change.” Likewise in health education, typically, those in positions of authority try to “change the behavior” of the poor and marginalized. But in Freire’s liberating approach, the poor and downtrodden try to change the behavior of the ruling class. To symbolize this bottom-up approach, after showing the above slide I showed a drawing of a group of poor farmers and laborers confronting a surprised group of doctors, businessmen, scientists, and politicians, collectively declaring “WE ARE GOING TO CHANGE YOU!” On seeing this slide, some of the professionals and officials in the workshop got quite upset, and asked me if I was try start a revolution. Other participants, however, were far more receptive. They noted how the entrenched inequalities in Burkina Faso contribute to marginalization and disability. In the course of the hands-on workshop, even many of the professionals and authorities came around to appreciating the importance of discovery-based learning. In planning the Inclusive Child-to-Child Workshop in Burkina Faso, the staff of Light for the World had decided to include activities that could help schoolchildren learn about some of the most common and serious health problems. Special emphasis was given to the needs of infants and preschool children where the incidence of preventable disability and death is especially high. Because good nutrition and early home management of diarrhea are of central importance with regard to protecting infant health, reducing the high child death rate, and preventing disability, it was decided that it would be appropriate in the Workshop to include activities to help schoolchildren learn about these two urgent interrelated health needs. Through hands-on “learning by doing” the children, the children could begin to take simple measures to protect the health of their baby brothers and sisters in their own homes. At the same time, every effort would be made to introduce and adapt these activities in ways that would make them as fully inclusive as possible for children with a range of disabilities … and to do by engaging all the children in looking for ways to welcome and involve those with a disability, A splendid example of discovery based learning is use of the Gourd Baby. Philippe showed the participants the Gourd Baby, while I presented slides of how children experiment with it to discover the signs of “too much water loss” (dehydration), and how to prevent it. Through their own experiments and observations with the Gourd Baby, children discover the danger signs of dehydration when a baby brother or sister has diarrhea. They also learn how to prepare a “special drink,” which, if they give enough of it in time to a baby brother or sister, can combat dehydration and even save the child’s life. For children to have these skills related to the home management of diarrhea is of critical importance in families when both parents are away working, and only school-aged children are left at home as the sole caretakers. Indeed, the idea of “Child-to-Child” grew out of the recognition that in poor families, school-aged children (especially the girls) often spend more time with their baby brothers and sisters than do their working mothers or fathers. If they can learn some basics about how to promote the health and development of the infants they care for, they not only help their siblings, but they learn skills that can come in very handy when they have children of their own. Another activity presented in the Workshop was about Nutrition. Here schoolchildren in a Child-to-Child workshop in Michoacan, Mexico, measure the upper arms of cardboard babies. They did this as practice for a survey they planned to make of “children-under-five” in their community, to identify which youngsters are “too thin.” After completing their survey, the pupils took action to help the “too-thin”children gain weight. They leared to do a variety of simple things, like making sure weaning gruels are made thick enough to be calorie rich, adding a bit of vegetable oil to the baby’s food, and giving food to the “too thin” toddlers more often. This slide from Mexico shows a blind child measuring the arm circumference of a cardboard baby, using a sting with knots in it, rather than a measuring tape, so the blind boy can measure by feel. On Day 2 of the workshop, participants had a chance to practice the activities that they chose to facilitate with the group of non-disabled and disabled children the following day. One of these activities was the Child-to-Child activity on Diarrhea, in which the children will experiment with the Gourd Baby to discover the signs of dangerous water loss (dehydration), and learn what action they can take to protect their baby brothers and sisters when they get diarrhea. Although I brought this Gourd Baby from Mexico (it has traveled to more than a dozen countries), similar gourds can be found in Burkina Faso. But where an appropriate gourd is unavailable, a plastic bottle can be used. It was necessary to practice the methodologies that the workshop participants planned to facilitate with the children the next day. The challenge will be to help the children discover the signs of dehydration without being told. Here the participants fill the Gourd Baby with water, then pull the plug in the backside, and ask everyone to observe what happens. The first thing they observe is that the soft spot or fontanel (a cloth covering the hole in the top of the head) sinks in. “Why?” asks the facilitator. “Because the water is running out!” the group answers. In a similar way, they discover the other signs of dehydration. Since the Gourd Baby has all the same holes that a normal baby has, participants can pull the plugs to learn the different signs of dehydration. No less important–as one needs to keep re-emphasizing–the Gourd Baby is also an excellent tool to introduce the art of Discovery Based Learning, whereby the teacher pulls ideas out of the children rather than pushing them in. However, this requires a big shift in teaching methods for teachers long used to a didactic, top-down style of teaching. Discovery based learning can be very challenging. It requires a lot of rethinking–and a lot of practice. An official from the regional Ministry of Education was enthralled with the discovery-based learning, and here takes photos of the process in action. The one sign of dehydration that cannot be taught with the Gourd Baby is the “skin-fold test.” To learn this, a sock with a small ball in it is stretched over the hand to represent a baby. The sock has a hole over the wrist. Someone is asked to pinch and pull the skin on the baby’s chest. With the wrist bent forward when the skin is pinched, the skin fold will remains obvious after letting it go (a sign of dehydration). But if the wrist is bent forward when pinched, the skin fold will disappear at once (no dehydration). In this workshop we used my wrist because the skin folds are more prominent on a skinny old man. Next came the nutrition activity, where participants practiced measuring the upper arms of cardboard babies. To measure the baby’s arms, they made 3-colored measuring strips. And to enable blind children to measure by feel, they made “measuring strings” with knots in right places (at 12.5 and 13.5 cm). After making the measuring strips, they practiced measuring the arms of the cardboard babies. To include this deaf participant, the sign language interpreter translated the instructions for me. Here the deaf participant measures the arm of a cardboard baby. After practicing a selection of activities, the participants divided into two groups. The next day each group would facilitate a separate workshop with a group of children, some of them disabled. Now was the time for them to decide upon, plan and organized agenda for the following day. But this process of “learning by doing” for some of the participants proved quite a challenge, especially for those in the first group, shown above. Many of the teachers and the officials in the Education Ministry, having themselves been schooled in a top-down, authoritarian system, felt more comfortable being told what to do than being asked to figure things out for themselves. But eventually they came up with their own plan of activities. The first group decided to focus on Child-to-Child activates related to seeing and hearing. In these activities, older children learn to test the vision and hearing of younger children who are first entering school. Also they try to figure out ways to help the youngsters with visual or auditory handicaps to be more fully included in the classroom and to learn with the help of others. This group also planned awareness-raising role-plays. The 2nd group chose to focus on the Diarrhea Activity with the Gourd Baby. In addition they chose the Nutrition Activity, to help schoolchildren identify infants who are “too thin” and then take action to try to improve their food intake. This group divided into 2 sub-groups to plan and coordinate these two activities, one on Nutrition, and one on Diarrhea. The sub-group on Nutrition decided they needed to make more cardboard babies, with a wide variety of arm thickness, so the children could simulate conducting a community survey, and learn how to tabulate their results. Their hope was that after the workshop the children would conduct a real survey of real babies in their community, and then do what they could to help those who are “too thin” gain weight. Helping in the planning and preparations of the 2nd group was a Peace Corps volunteer named Emily, whose fluency in both English and French was a big help (especially to me). On the big day of the workshops with the children, the official from the Department of Education helped organize the event. It was held at a primary school in Garango. With over 120 people taking part in the two Child-to-Child workshops—including 50 children, 16 of them disabled–things were a bit chaotic getting started. A member of the sub-group in charge of the nutrition activity arrived with an armful of cardboard babies they’d made the night before. With all the confusion, the action started more than an hour late. But the children were surprisingly patient. In addition to the 50 children selected to participate in the workshops, the school yard was replete with other curious youngsters. Of the 16 disabled children, 4 were blind, 5 deaf, 5 physically disabled, 1 intellectually disabled, and one was a short person with impaired legs. Although most of the children in the workshops, including the disabled ones, were in the 6th grade of primary school, their ages varied greatly. Currently in Burkina Faso there are few new cases of polio, thanks to vaccination. Yet there are still many older children, like this 16-year-old, who must cope with the residual paralysis caused by polio in their early years. A lot of the assistive equipment in Burkina Faso is provided by foreign NGOs. However, many aids, such as the hand-powered tricycle on which this boy came, are made locally, some by disabled crafts persons. Also, his leg braces were made by a local technician, himself disabled. The two simultaneous workshops were held in adjacent classrooms. The children sat on one side of the classroom, the facilitators-in-training on the other. For an “icebreaker,” the night before one group of facilitators had prepared drawings on pieces of cardboard. These they cut in half and randomly handed them out to the children. Then the each child was asked to look for his or her “other half.” After finding each other, they would spend a few minutes getting to know each other. Finally they would take turns introducing their new friend to the plenary. In order to include the blind children in the ice-breaker, the pieces of cardboard were cut into different shapes and then cut in half, so a blind child could look for his “other half” by touch rather than visually. This boy must look for the other half of his cardboard fish. A blind boy was first shown the two halves of the fish and how to fit them together by feel. This blind girl with half a chicken needs to find her “other half.” And after some hunting, at last the two halves meet. As part of a “community diagnosis,” activity, sheets of paper were handed out. Each child asked to draw a “common problem that affects health and well-being” in their community. To get a wider spectrum of health-related problems, the children were asked to draw a problem different from that of the child sitting on either side. The children took the project seriously. The boy on crutches drew this picture of himself. However one child wasn’t participating! Unfortunately, when the drawing paper was handed out, no one noticed that this girl in a wheelchair had nothing firm to support her sheet of paper. Even though the purpose of the workshop was to sensitization to disabled children’s needs, at first everybody overlooked this very obvious one. At last, after some prompting, this deaf girl saw the problem and with the help of the sign-language interpreter, pointed it out. This boy resolved the difficulty by placing a stiff folder under the girl’s paper. But even so, the girl was too nervous and afraid to start drawing. So the boy gently helped her get started. With the friendly atmosphere, the girl began to relax. And soon she was drawing by herself. By the end of the workshop she had made new friends and participated eagerly. She looked much happier and self-assured. While the other children were drawing, this blind girl recorded in Braille the problem she had selected. The other children marveled at the blind girl’s ability to write and read by touching with her fingers a pattern of tiny raised dots. This helped them appreciate her strengths rather than just see her weaknesses. The eagerness of the children and their openness to the new perspectives of inclusion were inspiring. Beginning the activity on Management of Diarrhea, one of the teachers introduces the Gourd Baby. Some of the children volunteered to conduct the experiment with the Gourd Baby. First they filled the gourd with water. Then they began to experiment to discover the different signs of dehydration. To be inclusive, the facilitators had one of the blind children feel the Gourd Baby. At first, it was the adults who took the initiative to include the blind children.But with a few reminders, the grown-ups let the schoolchildren themselves take responsibility for making sure the disabled children were included. The children caught on quickly, and eagerly took turns in this inclusive process. The blind children were delighted. They made sure each blind child had a chance to feel the different features of the Gourd Baby. After covering the hole in the top of the gourd with a cloth to form the “soft spot” the children let the blind youngsters touch the soft spot again, and feel how sinks in when the water runs out. Here the children discover how the stream of pee slows down and then stops when as the Gourd Baby looses liquid. Enthusiastically, through the own observations, the children discovered the different signs of dehydration and wrote them on the blackboard. To find out if dehydration can be dangerous, the children compare a leafy plant left in water, and one left without water. When asked, “What they think happens to a baby without enough water?” they conclude, “Maybe it too shrivels up and dies!” They make sure the blind children have a chance to feel the plants, with water… and without…so they can draw their own conclusions. At the start of the workshop, this blind girl looked unhappy and withdrawn. But with all the attention and interaction, she began to smile, speak out, and get involved. After discovering the signs and dangers of dehydration, the children learned to make a “special drink” to prevent and combat it. With a home-made measuring spoon, they measured the right amounts of sugar and salt in a glass of water. To be certain the Special Drink they’d made was safe, they asked the blind girl to taste it, and make sure it was “no saltier than tears.” While the children in the workshop were engaged in all these discovery-based activities, a crowd of village children peered in through the windows, wide- eyed with curiosity.I thought this “window watching” audience was a great way to spread the new ideas to more children. Unfortunately one of the teachers in our workshop angrily tried to run the window-watching local children away. This led to an eye-opening discussion about the importance of an “open door policy” to “inclusive education,” and the value of letting “outsiders” observe. The Nutrition Activity began by teachers asking the children if they think it is dangerous for a baby to be “too thin” - and how they can find out which babies might be at risk. In preparation for the Nutrition Activity, facilitators in that group had made a batch of cardboard babies for the children in the workshop to practice measuring which babies were “too thin.” The goal was that afterwards, with the help of their teachers, they could conduct their own survey of “under-fives” in their village, and look for solutions to help those who are “too thin” put on weight. To give realistic measurements to the arms of the cardboard babies, the facilitators taped padding on the back of the babies’ forearms. Here the children in this activity carefully make their arm-measuring strips. … … They measured and colored the strips into three zone, to indicate which infants and toddlers are “too thin,” (red), “marginal” (yellow), and “OK” (green). The yellow “marginal” band falls between 12.5 and 13.5 cm. Here a boy helps a blind girl make a “measuring string” with the same 3 zones marked by knots, so she can measure arm circumference by feeling the knots. This is a good example of the way the children learn to work together and look for ways to adapt to each child’s special needs. Now the children begin to measure the cardboard babies and record their findings. This plump baby measures in the green. … … And this skinny baby measures in the red. After measuring all the babies, the children use match boxes to make a 3-dimensional graph of their “survey” findings. They color the ends of match boxes—red, yellow, or green—according to their findings for each baby. The baby that this boy measured was “too thin.” His match box is red. By stacking the matchboxes in 3 columns, the children create their “graph” showing the nutritional status of the babies they measured. Later, with the help of their teachers, they can conduct a real survey of the under-five babies in their communities. Then they make an effort to see that the “too thin” babies get high-calorie snacks and eat more often. Then they can repeat their study to see if fewer are too thin. In this way, schoolchildren can make a real contribution to child health in their communities. In this activity the children learn to test one another’s vision. Later, at school, these 6th graders can test the vision (and hearing) of 1st graders who are just entering school. When they identify a child who can’t hear or see well, the children can think of simple ways to make sure that child is not left out, like having her sit up front where she can see the blackboard or hear the teacher better. Or perhaps a friendly child can sit next to the one who can’t see or hear well, and make sure she understands. It is important that these ideas for inclusion come from the group of children, challenging their creativity and imagination. In this visual testing, the children made sure to fully involve those with disabilities. Here the girl with short stature tests the vision of a deaf boy.I loaned her my walking stick to point to the letters. This improvised role play, performed by both the adults and children in the workshop, portrays a teacher who makes no effort to include a child who is blind, until the other pupils, led by a child who is physically disabled, insist she make a greater effort to include the blind child, and treat him with respect. For the benefit of deaf persons present–including the deaf boy who acted the blind one–the sign-language interpreter translated everything. On leaving the Workshop for a break, two of the blind children stick together: Disabled-Child-to-Disabled-Child. Also the blind girl and her “other half” from the icebreaker game have maintained their friendship, and the sighted boy in the green shirt helps guide his blind companion. Meanwhile, it is the village children outside the workshop who practice Child- to-Child in their day to day lives. In this game a blindfolded child stands in a small circle of stones… … and the children take turns trying to sneak up and steal a stone without being heard. If the blindfolded child hears the robber, she points at him, and he’s out of the game. The boy on crutches at first did not join this game. He sat under a tree. But then the other children invited him to join. Everyone was amazed how silently the boy could move on his crutches. This blindfolded girl, although her hearing is normal, was unable to hear most of the children as they sneaked up to steal the stones … … Then they asked a blind girl to stand in the circle of stones. Her hearing proved to be much sharper than the children who could see. Almost no one could steal a stone. Everyone was amazed at the blind girl’s extraordinary hearing. It helped them focus on her ability, not her disability. They saw how a person who is weak in one area can become outstandingly skilled in another. To help non-disabled children better understand those with disability, they played simulation games. Here a young athlete has one leg tied up so he has to hop along using a crutch. Then the young athlete and the boy on crutches ran a race. The race was a tie! Now the young athlete has greater appreciation for the disabled boy’s ability . And so does everyone else! All the children applauded. At the end of the Workshop everyone–young and old, disabled and non-disabled—joined together with a new sense of solidarity… … and raised their hands in the local sign language for inclusion. The evaluation the next day involved all those present in the Workshops, both children and adults. My translator had been a great help to me throughout the Workshop—although my own language handicap had slowed things down a lot. To start off the evaluation, small groups were formed to discuss the strengths and weakness of the workshops and to write a summary on poster paper. The disabled children here formed their own group. And the sign language interpreter, as he had done throughout the Workshops, translated for those who were deaf. Each group discussed what they had learned in the Workshop, and how they might put it to use afterwards, and they carefully wrote down their conclusions. They liked the fact that they were included in the evaluation, and that their ideas were considered important. The adults split up into the same two groups that had facilitated the simultaneous workshops with the children, to discuss what they’d learned and how things might be improved. This is the group of adults who led the Gourd Baby and Nutrition activities. And this is the group that facilitated the activities on hearing and seeing. The Catholic priest who coordinated the discussion is a leader of the local Diocese that promotes inclusive education and Community Based Rehabilitation. In the closing plenary, each of the small groups presented their posters and summarized their observations, welcoming discussion by the entire assembly. (Unfortunately time ran out and the final discussion was cut short.) First to present were the disabled children. Overall they were very happy with the workshop, and the fact that their participation and concerns had been so central to it. They pointed out that, with their disabilities, many had at first been nervous about the workshop. They had feared they would be pitied or made fun of. But by the end of the workshop they felt at ease and respected by the other children, and they had made a lot of friends. They enjoyed the chance to show off their skills, like better hearing, or Braille. All the groups of children spoke up with confidence and had important observations. Many took an active part in presenting their ideas, showing that they had captured the spirit of inclusion. All said they enjoyed doing things with the disabled children, learning to appreciate their abilities and becoming their friends. While the children’s groups enjoyed all the Child-to-Child activities and felt they learned a lot, what topped their list was the Gourd Baby. They liked experimenting with it to learn from their own observations. Their enjoyment was enhanced by including the blind children in each stage of the process. We were all impressed by the careful and caring way the children expressed themselves, and by their eagerness to put what they had learned into practice in their school and community. After the 3 children’s groups presented their evaluations, the two adult groups followed. For the most part they felt very positive about the workshop. They said they’d learned a lot, not only about ways to make schooling more inclusive for children who are different, but also about ways to make it more relevant and empowering for ALL children. They liked the methodology of discovery based learning, and of encouraging the children to work together to solve common problems. Some of the adults felt that planning of the workshop had not been sufficiently directive. They hadn’t been given precise enough instructions about just what they were supposed to do, and how. But others of the adults disagreed. They declared that discovery based learning was not just for the children but also for themselves. This set off a debate about obedience training versus education for change. It struck me that the children were much more open to discovery based learning than were some of the grown-ups. There was disagreement on some issues. But everyone agreed that the inclusion of the disabled children in the Workshop–and the participation of all the children in the evaluation–was important to achieving the goals of the Workshop. Likewise there was general agreement that giving an empowering voice to the children by letting them think for themselves and seek solutions collectively may in the long run have great socio-political importance. Such educational practices could give rise to a new generation of “agents of change” who will help transform Burkina Faso–and the world–into a fairer, more inclusive and more equitable environment, where people of all classes and backgrounds can work together for the common good. Who knows how far this larger vision behind the Workshop may spread? Clearly, the real “evaluation” will depend on what happens afterwards. The adult participants were chosen as potential “multipliers” who can take the ideas for inclusive “education for change’ into the classroom and community. Perhaps some of the methods will be put into the school curriculum. Already several children and teachers are talking about introducing into their classrooms or communities some of the activities and methods they learned. Some, for example, were interested in organizing 6th graders to test the vision and hearing of the children just entering school, so they can befriend and assist those who can’t see or hear very well. Other teachers and children talked about doing a community survey, measuring the arms of babies in order to better the chances of those who are “too thin.” Perhaps the best measure for an evaluation is the “SMILE FACTOR.” Scaling up DISCOVERY BASED LEARNING and the role of CHILDREN AS JUNIOR HEALTH WORKERS and BUDDING AGENTS OF CHANGE The undisputed star of the Workshops in Burkina Faso–as in workshops in many countries–was the Gourd Baby. This hands-on teaching aid had a big impact in the workshop, and promises to continue to do so in the future. Already the Light for the World team has recruited local artisans make two such babies out of local gourds. One of these has already traveled to Ethiopia. There it will be used by Marieke (LFTW’s regional trainer for CBR and Inclusive Education) to teach children (and mothers) about the management of infant diarrhea. If enough children begin to think for themselves and work together for the common good, perhaps humanity still has a small chance of learning to live in harmony with one another and in sustainable balance with the world of nature on which our survival depends. It’s worth a try. THE END … and hopefully a drop in the bucket toward a NEW BEGINNING.Photo Essay: David Werner’s Visit to Burkina Faso

Part 1: Visits to Disability Programs

The Ouagadougou Center and School for the Blind

Visits in Kaya

The Community-Based Rehabilitation Projects in Kaya

Center for Deaf Children in Kaya

The Morija Orthopedic Center in Kaya

Home Visits in Kaya

Part 2: The Child-to-Child Workshop

Pre-Workshop Meetings

Day 1: Presenting the Central Ideas

Helping Schoolchildren Learn about Common Health Problems in a Hands-on, Inclusive Way

Discovery-Based Learning about Diarrhea and Dehydration, with the Gourd Baby as the Teacher

An Example of ‘Participatory Epidemiology’ Conducted by Schoolchildren: The Child-to-Child Nutrition Activity

Day 2: Planning and Practicing Selected Activities to be Facilitated the Following Day with the Schoolchildren

Practicing the Nutrition Activity—Finding Out which Babies are ‘Too Thin’

Day 3: The Two Child-to-Child Workshops in Garango

Ice-Breaking Activity

Community Diagnosis through Drawings

The Activity on Diarrhea with the Gourd Baby

New Perspectives on ‘Inclusion and Exclusion’

The Nutrition Activity

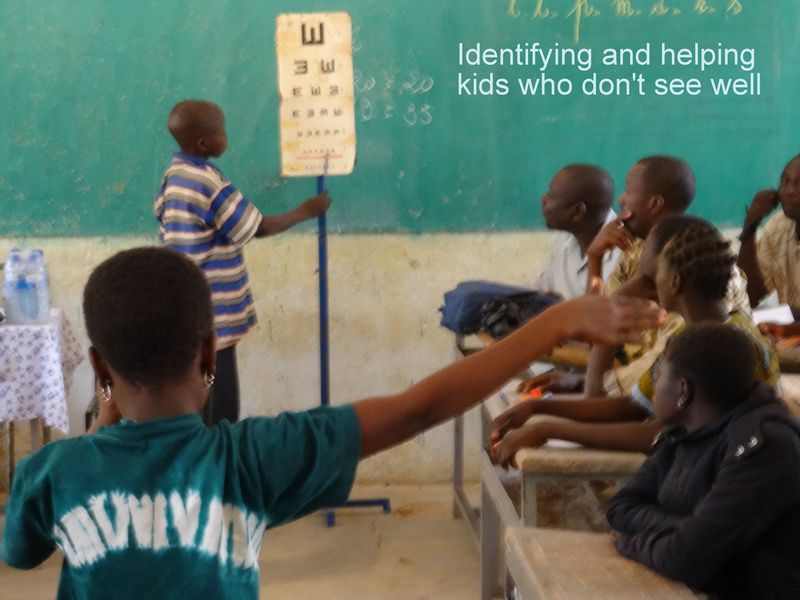

Identifying and Helping Children Who don’t See Well

A Role-Play About Inclusion in the Classroom

Examples of Child-to-Child from the Workshop and Beyond

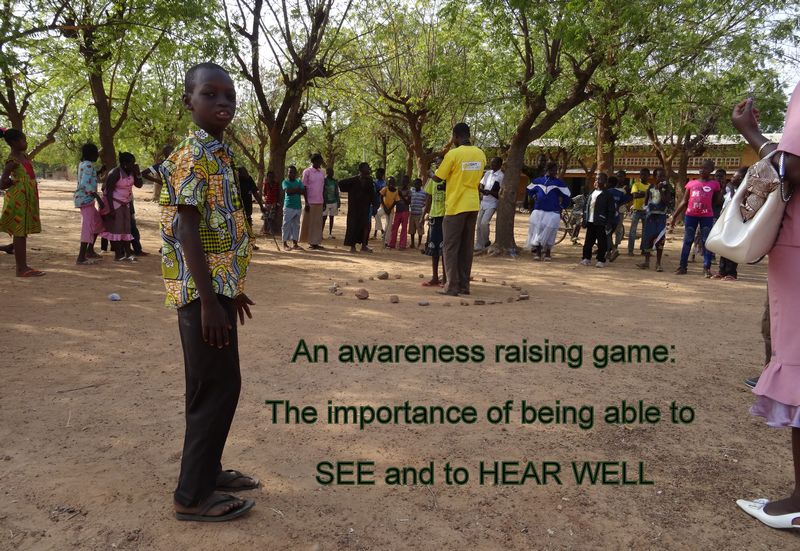

An Awareness Raising Game: The Importance of Being Able to SEE and HEAR Well

Simulation Games with a Pretend Disability

Closure of the Workshop: New Awareness, New Ideas, New Friends

Day 4: Evaluation

The Gourd Baby

End Matter

Board of Directors

Roberto Fajardo

Barry Goldensohn

Bruce Hobson

Jim Hunter

Donald Laub

Eve Malo

Leopoldo Ribota

David Werner

Jason Weston

Efraín Zamora

International Advisory Board

Allison Akana — United States

Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia

David Sanders — South Africa

Mira Shiva — India

Michael Tan — Philippines

María Zúniga — Nicaragua

This Issue Was Created By:

David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings

Jason Weston — Editing and Layout