Making A One-Room Village School More Accessible For a Nine-Year-Old with Muscular Dystrophy

|

|

|

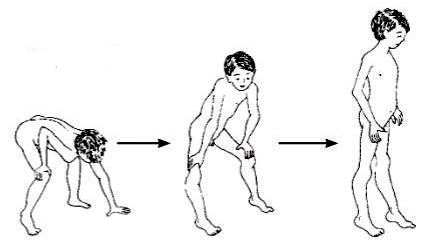

Like many children with congenital disabilities in rural Mexico, Juan Antonio—or “Tonio” for short—was given to and raised by his grandparents, who live in a small village called Tablón #2, south of Mazatlan. From around three years old, Tonio began to show signs of increasing physical weakness, especially in his legs. He tripped and fell frequently, and had increasing difficulty getting up off the floor, and climbing steps.

This unusual weakness was especially troublesome at the home of his grandparents, which is perched on a steep hillside overlooking the village. And it became an even bigger problem when Tonio started school.

The tiny one-room schoolhouse is located on a facing hillside, and has two sets of stairs, one with 8 steps, the other with 4. The steps are steep, of irregular height and depth, and are without handrails.

During his first years of schooling, Tonio could climb these steps by himself, be it with difficulty and occasional falls. But now, at age nine and in the 5th grade, to go up these steps safely he needed help—for which he feels ashamed to ask.

|

|

|

This year the small village school has only 11 pupils—from 1st to the 5th grade—and a single teacher, who instructs them all.

During his first three or four years at school, Tonio was miserable. Some of the older children teased him for the odd way he walked, and called him a wimp. Tonio became very withdrawn. He would sit by himself in the far corner of the classroom and was too shy to speak. The teacher scolded him for not participating.

Now, in his 5th year, things had become somewhat better. The new teacher, a young man named Alfonso, has done his best to include Tonio and to encourage his classmates to befriend him. But, by now, Tonio had become so timid and withdrawn that there was almost no interaction between him and the other children. The teacher, over time, gradually won the boy’s trust to the point where Tonio sometimes spoke to him when they were alone. But when other children were present, he rarely said anything beyond a muffled “Si” or “No.” Regardless of what is going on around him, his face always had the same, quiet, far-off look that made it difficult to read his emotions.

Recess brought another problem. Despite the teacher encouraging him to go out and play with the others, Tonio would sit placidly at his desk, reading his schoolbooks. Once again, the sets of stairs were an obstacle; they separated the schoolhouse from the spacious playground, which is located on a lower level. At recess, the flock of children would dash out of the school and bound down the steps to the playground—leaving Tonio behind. And even when the teacher would shepherd him outside and help him down both flight of steps, the boy would just stand at the edge of the playground, silently watching.

Meeting Tonio

I first learned of Tonio several months ago from my close friend, Polo Ribota, who since childhood has been deeply involved in our community-based rehabilitation efforts. In my old age, Polo and his family have built a house for me next to theirs in the village of Tablón Viejo, just down the road from Tablón #2. Polo, who is a friend of Tonio’s grandfather, told me that Tonio, “has trouble walking,” and took me there to see what advice I might have.

Tonio’s diagnosis of Duchene’s Muscular Dystrophy had been made a couple of years before by a pediatrician in Mazatlán. Although there was no known family history, the boy´s progressive weakness, his characteristic gait, his hypertrophied (oversized) yet weak calf muscles, and the way he pushed down on his weak thighs with his hands to stand up or climb stairs, led me to believe the diagnosis was correct.

View Chapter 10 on Muscular Dystrophy from David Werner’s ‘Disabled Village Children’ [Table of Contents]

Although the medical diagnosis had been made by doctors, and a muscle biopsy had been performed to confirm it, no one had explained to the family what muscular dystrophy is or what to expect—except that the weakness would gradually increase, and that there is no known medical treatment.

I did my best to explain the disability to the grandparents. I emphasized that although the condition is progressive and life expectancy is short, there was a lot that could be done to help the boy live as happy and fulfilling a life as possible, despite his increasing physical limitations. I pointed out that Tonio has a good mind, and should be given every opportunity to develop and use it. Effort should be made to have him stay in school, and to make schooling a positive and enabling experience.

I also did my best to talk to Tonio, to and try to win his trust. But I soon realized this would not be easy. The boy just looked at me with big wondering eyes, never saying a word. “That’s how he is with everyone,” said his grandmother, “except with us … and only when we’re inside the house alone. Then he’ll chatter away—but he almost never mentions his worries or himself.”

His grandparents were concerned that, on the hillside where they lived, the series of crude steps to get up to and into the house made coming and going an ordeal for the boy. And the problem was getting worse.

I encouraged Tonio’s grandfather to consider building ramps, with railings, and gave him some pointers. The next time I came to visit (several weeks later, as I had been traveling), I was delighted to see the ramps in place and Tonio successfully using them. As the boy showed me how he used them, as ever, he made no comment. But the hint of a smile as he went up and down the main ramp, holding onto the wooden railings, revealed a glimmer of pride in his improved self-reliance.

The main ramp, while steeper than typically recommended, serves three purposes quite well:

-

It provides easier, safer accessibility for the boy, allowing independent entry to his home.

-

It supplies good exercise for his weakened thigh muscles: neither too much no too little for his current dystrophic state. (Too strenuous exercise can increase muscle loss.)

-

It stretches his tight heel-cords by bending his feet upwards as he climbs the ramp. This important stretching exercise helps prevent the Achilles tendon contractures common in muscular dystrophy. (With such contractures the child has to walk on tiptoes, which causes greater instability and earlier loss of ability to walk at all.)

Physical Disability as Generator of Emotional Handicap

Tonio’s greatest asset is his brain. The boy is intelligent and has a curious mind. He likes to read, especially about dinosaurs and astronomy. Perhaps his being a “book worm” stems from his physical limitations. But, for whatever the reason, his reading level is advanced for his age.

Tonio still has mixed feelings about school. He likes the stories in the books. And, little by little, he has come to like—and in private, even speak to—his current teacher. But, for Tonio, school also has its distressing downsides:

First: Getting to school is an ordeal. The most direct route from home is over a rough footpath that is quite steep in places. Though only a 10 minute walk, he can no longer do it by himself. Every morning his grandmother walks with him to school, providing necessary support. On arrival, she helps him up the two flights of steps in front of the school, and then she walks back home. At noon, when the children go home for a lunch break, she walks again to the school to escort Tonio back home. Although the other pupils return for the afternoon session, Tonio does not. The hot afternoon walks are too exhausting, both for him and for his grandmother. To make up for what he misses in the afternoon lessons, the teacher assigns him extra homework—which Tonio, like most schoolboys, hates—especially the math.

Second: At school Tonio is very much a loner. The big bullies from earlier years are now gone and the present children are basically amiable. The teacher encourages them to befriend and include the isolated boy. But Tonio is so withdrawn and silent that the other kids tend to give up on their efforts, and just ignore him. In some ways, Tonio’s emotional isolation and paralyzing sense of shame have become a greater handicap than his physical disability.

Third: The physical barriers at the school add to the above problems. The precarious flights of steps, which also separate the schoolhouse from the playground, isolate him even more. Ashamed to ask for help in coping with the steps, he sequesters himself in the classroom while his peers romp together in the playground. So it is that the physical, social and psychological barriers amplify one another.

Child-to-Child Activities to the Rescue

After discussing Tonio’s situation with his teacher and grandparents—and as best we could with the boy himself—we decided to facilitate “Child-to-Child” activities in the classroom and playground. Our goals were to sensitize his classmates to Tonio’s needs and possibilities, to explore ways to include him more fully and to make school more accessible.

To learn more about the Child-to-Child methodology, in general, see Chapter 24 Helping Health Workers Learn by Werner, D. and Bower, B. [Table of Contents]

For Child-to-Child activities for inclusion of disabled children, see David Werner’s books:

-

Chapter 47 from Disabled Village Children [Table of Contents]

-

Part 6 Nothing About Us Without Us [Table of Contents]

Click here for information about all our books including printed copies.

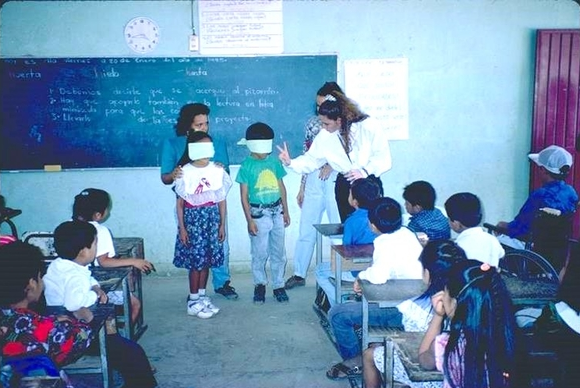

One morning Polo’s wife Felipa and I went to the school in Tablón #2 and met with the children. We started with a slide show showing Child-to-Child activities in other schools, ranging from Nicaragua to Michoacan, Mexico.

Fortunately—as part of a national attempt to modernize education—the little school in Tablón #2 was equipped with a fancy computer linked to an overhead projector. Unfortunately, neither worked. Luckily, as a backup I’d brought my laptop. Its small screen was no problem; the 11 pupils happily crowded around it, and viewed the presentation at close range.

A key part of the slide show was the true “foto-historia” of Jesus, a partially blind boy with spina-bifida. At age 10, Jesus had just started school for the first time. This was in the village of Ajoya, where at that time PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) was located. Though Jesus had begun school eagerly, he soon grew discouraged because other students teased him and the teacher scolded him for not being able to read the blackboard. Fortunately, however, this situation was greatly improved with the help of Ramona, a disabled young woman visiting from Nicaragua, who facilitated a Child-to-Child activity in Jesus’s classroom. To sensitize the children, Ramona had them play games simulating different disabilities, and then discuss what it felt like to be made fun of or left behind. Next, she asked the children think of ways they could help Jesus participate more fully, both in their studies and their games, despite his physical and visual handicaps.

Click here to read the complete story of Jesus from ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ by David Werner.

These eye-opening activities were so transformative for both the students and their teacher that they became much more understanding and inclusive of Jesus. Likewise for Jesus, the experience was so motivating that, as a part of PROJIMO’s community outreach program, he eventually became a Child-to-Child facilitator himself.

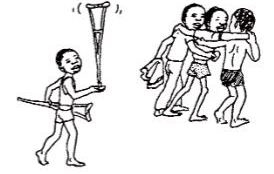

I then showed slides of the first such Child-to-Child event that Jesus helped to lead. In the village of Limon, two brothers with muscular dystrophy had been teased so cruelly by their classmates that they refused to go to school anymore. To remedy this, Jesus, among other activities, involved the school children in helping make therapeutic playground devices in the two brothers’ backyard. The social dynamics improved so much that the brothers, when coaxed to give school a second try, were eagerly welcomed by their classmates. In this way, children learn to derive satisfaction by looking for ways to include and help, rather than exclude or torment, the child who is different.

|

|

|

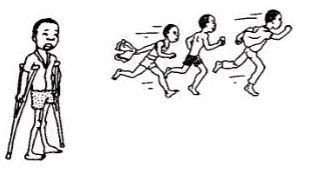

As a part of the activity with the schoolchildren in Tablón #2, we also showed slides where children in another village put on a brief skit. The skit had two scenes. In the first, a group of kids on a hot summer day run excitedly toward the river to swim, leaving Pedrito, a youngster on crutches, unhappily behind. In the second scene, the same group of kids invites Pedrito to go with them.

After this skit, we asked the children if it gave them any ideas regarding Tonio. They said they wanted to be sure to include him more in their activities and games. Hearing this Antonio blushed—and almost smiled.

Following the slide presentation and some spirited discussion, Tonio’s classmates were eager to play some simulation games. To this end, they all sprang to their feet and dashed out the door and down the steps toward the playground—ironically leaving Tonio behind. As usual, Tonio remained mutely in his chair, with his vacant look of quiet resignation.

But then, something happened! Half way down the steps, a small girl stopped and cried out, “What about Tonio?” Then they all stopped, turned around, and rushing back into the classroom, asked Tonio to join them. At first Tonio refused. Then he silently rose to his feet. The other children scrambled around him like ants around honey.

|

|

|

Tonio silently accepted all this attention, but behind his overt expression of embarrassment was a glimmer of approval.

On the playground, the children took turns simulating a physical disability. Everyone wanted to play the disabled child.

As usual, Tonio stayed on the sidelines. To include him, they tried to make him referee, by having him say, “On your mark, get set, go!” But Tonio wouldn’t open his mouth. So they asked him to hold up his arm and lower it as the signal “Go!” Little by little, Tonio accepted this role.

The four children who had raced with a simulated disability stood in the middle of the circle. They were asked questions like:

“What does it fell like to be left behind?” … “or to be laughed at when you stumble or can’t keep up?”

Finally, all the children were asked, “What are some games you can play in which a child with a lame leg, or who can’t run, can take part just as well as the rest of the children?

Some of the schoolkids suggested games such as “marbles” or “jacks” or “pick up sticks.” But most of the children suggested active group games they already played on the playground. Some were the equivalent, or variations of, “musical chairs.”

The schoolteacher suggested they actually play some of these games, making a point to include Tonio. So they did so.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Identifying and Overcoming Barriers

As a part the activities with Tonio’s class, we asked the children what they thought some of the problems or obstacles might be that make it difficult for Tonio to take part fully and happily in school. The children identified the following difficulties.

-

Getting from his home to the school is hard. The trail is steep and rough. Tonio’s grandmother has to walk with him and provide support.

-

For this reason, Tonio goes to school only in the mornings. It’s too tiring, both for him and his grandmother, to also come in the afternoon, when it is often brutally hot.

-

To get into the schoolhouse, the two steep flights of steps are a major barrier and hazard especially since there are no railings.

-

The steps are also a big obstacle to Tonio’s participation on the playground during recess. Tonio can’t manage the steps safely alone and is embarrassed to ask for help.

“What actions might we take to overcome these difficulties?” we asked the children. They had a lot of ideas.

One girl suggested that families who had cars could take turns driving Tonio to and from school every day. The teacher pointed out that while this was a good idea, it was probably too idealistic.

A boy suggested, “At least we could help level out the rough areas of the trail.” Everyone thought that was a good idea.

As for the steep flights of steps to get to the school, some children suggested putting up railings. Others thought it would be better building ramps.

We discussed these various alternatives with the children and the teacher, and as best we could with Tonio, whose shy responses were limited to a muffled “Si” or “No.”

Taking into consideration the boy’s physical condition, the anticipated course of his muscular dystrophy, and his therapeutic needs, we finally came up with a plan of action and assistive equipment, which included the following.

A Spider-like Wheelchair Carriage

As for getting from home to school, as long as Tonio was still able to walk reasonably well, it made sense for his grandmother to keep walking with him to school every day. This moderate amount of exercise would help keep his muscles as strong as possible, despite their gradual deterioration.

But, since Tonio and his grandmother only had stamina to walk to and from school in mornings, in order that Tonio to be able to attend the afternoon session, some kind of transport was needed. Perhaps a wheelchair. But on the steep, rough trail between his house and school, a standard wheelchair would be useless—and dangerous! And even it were specially adapted, who would push it?

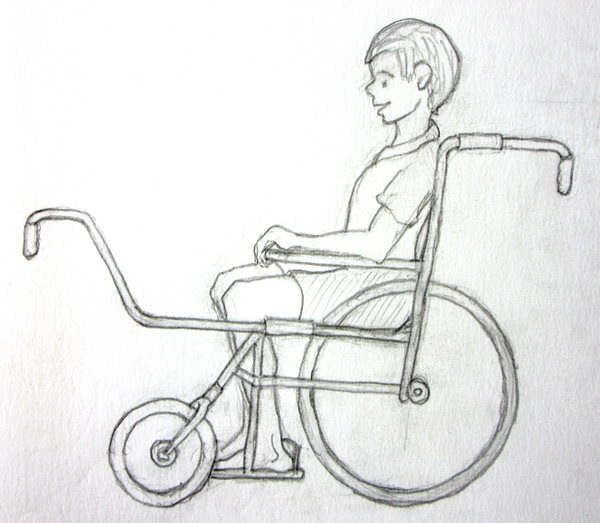

With these questions in mind, I drew the following sketch of a “wheelchair cart,” adapted both for difficult terrain, and for the possibility of being pushed/pulled by a group of 4 or more small children.

The sturdy design has extra-large, widely spaced caster wheels in front, and broad mountain-bike tires. It also has four long, spider-like extension “arms” so that several children can handily push and pull it from both front and back.

I showed the drawings to Tonio and his classmates and asked them, if such a child-drawn carriage were made, would they be willing to transport Tonio daily to and from his home to the school, so he could attend the afternoon session. The class unanimously cried, “Yes!”

We asked Tonio if he liked the idea, and after a moment’s hesitation nodded yes.

It was apparent, however, that Tonio had mixed feelings about the device. And the teacher, who had got to know Tonio’s grandparents fairly well, felt they too might have reservations about providing their grandson with a wheelchair.

This we could understand. For persons who have progressive weakness or increasing difficulty walking, it is often difficult for them—and their loved ones—to accept a wheelchair. To do so is somehow to “give up hope.” To them, being “confined” to a wheelchair means resigning oneself to being “invalid” or a “cripple,” which they equate with being useless, helpless, unattractive, lacking value, and unable to lead a rewarding, productive life.

Such negative conceptions about disability are very common, and not easy to change. But it is crucial to get beyond them, to recognize that even people with profound disability can often lead fulfilling and happy lives. Getting to know disabled persons who are doing just that is important for someone struggling to accept their disability. For this reason, in my slide show for Tonio and his classmates, I included photos of wheelchair users who devote their lives to designing and creating customized wheelchairs for disabled children. I told the children that Tonio’s unique “child-drawn carriage” would be made by a team of wheelchair riders in PROJIMO Duranguito.

And so the “all-terrain spider carriage,” as it became known, was made. Raymundo, a paraplegic, wheelchair-using leader of the Duranguito team, took personal responsibility for the construction of the carriage. It was completed and beautifully painted within a week.

When we took the carriage to the school, everyone was excited about it—with the exception, perhaps, of Tonio. All the children wanted to try it, both as riders and pushers. We let them test it out before Tonio tried it, and their overflowing enthusiasm with the strange carriage was what I think proved contagious for Tonio.

I had worried that Tonio might refuse to use the strange device. But when his turn came, he willingly got into the carriage and let the other children push/pull him around the spacious playground, trying it out.

|

|

|

|

Now it was time for the real test run: from the school to his house. Tonio’s grandmother had come to accompany the expedition. The schoolteacher, a bit nervously, also joined the brigade. All Tonio’s classmates were chafing at the bit to help transport him in the spider-mobile. And with its long arms projecting fore and aft, as many as 7 or 8 youngsters could all push and pull it at once.

|

|

|

To everyone’s delight, when we reached the irregular trails with sand, loose rocks and steep ups and downs, the group of children effortlessly navigated the strange vehicle in a surprisingly smooth ride.

When we reached his house and Tonio dismounted, we asked him if he liked his new spider carriage. With the biggest smile I had yet seen him give, he replied an emphatic, “Yes!”

Little by little, his grandparents—who at first had serious reservations about their grandson using a wheelchair—have become more comfortable with the idea, and they are pleased to see him interacting more with the other children.

Thus it seems this strange “daddy-long legs” mobility device has accomplished several objectives at once.

-

It has provided the means for Tonio to attend the full day of school.

-

It has provided an adventurous way for him and his classmates to interact more fully and joyfully.

-

It has helped both Tonio and his grandparents begin to accept the intermittent use of a wheelchair, which, as his muscular weakness progresses, will eventually become his primary means of mobility.

-

What’s more, the boy, along with his classmates, has learned that wheeled mobility can be fun!

Making the School Steps Safer and More Accessible

Once the difficulty in getting to and from home to the school-grounds was, in large part, resolved with the child-drawn carriage, the next physical barriers to deal with were the two steep flights of steps at the schoolhouse. Something needed to be done to make it easier to get into the school, and to get from the schoolhouse to the playground during recess.

One of the possibilities we considered was to build ramps. However, a simpler, if more short-term, alternative would be to install railings for the steps.

Ramps clearly would theoretically provide a more long-term solution. In a few years, with his muscular dystrophy, Tonio’s body will become too weak to walk; he will then get around principally in a wheelchair. Stairs will no longer suffice, and ramps will be needed.

But, for the time being, Tonio can still walk. Be it with difficulty, he can still go up steps by pushing on his weak thighs to provide additional force. But the steep steps ascending to the school, without handrails, are too difficult—and too risky—for him to climb without assistance. And when he has to be assisted he feels ashamed.

One advantage of railings over ramps is that they would be quicker, easier, and cheaper to install. Another advantage concerns Tonio’s physical capacity. By continuing to climb the steps daily while he can, he would get exercise he needs to keep his weakening body in as strong condition as possible.

It will probably be two or three years until Tonio becomes too weak to climb steps, even with a railing. By then he will have graduated from primary school and, hopefully, be attending secondary school in a neighboring town where there is one. So it seemed reasonable to hold off on ramps for the time being, and look to the short-term solution: railings.

For the necessary materials, Polo bought some old steel pipes cheaply in a scrap metal yard in Mazatlan.

The pipes were then welded by the disabled workers at PROJIMO Duranguito.

To install the railings we felt it would be a good idea for the families of the schoolchildren to help do the work. This activity could help get the community more involved in understanding and responding to the needs of those who are more vulnerable. The teacher agreed with this “community involvement” in principle. But based on his experience, he thought it would be very difficult to gain the participation of adults in Tablón #2. Community spirit was at a low ebb. Poverty was increasing, and many families had moved to what they hoped would be greener pastures. The teacher had a hard time even getting parents to come to meetings about the education and well-being of their own children.

Tonio’s grandfather had similar doubts, and offered to install the railings for the school steps by himself. However, he agreed that to raise community awareness and cooperation, getting the families involved in installing the railings was a good idea.

So we gave it a shot. The “railing-raising” date was set on the next Sunday at 4:00 PM, when most fathers would be home from work, and when the heat of the day would be subsiding. Although this was during the Easter holidays and school would be closed, Felipa and I talked to some of the children, who spread the word, like a grapevine. Also, the teacher sent a cell-phone message to all of the parents. But he was still less than optimistic.

To our delight, the response was fantastic. Although there are only 11 pupils in the school, nearly two dozen parents and relatives showed up—mostly fathers, but also mothers, grandparents, and siblings—as well as some of the schoolchildren.

With all these volunteers, the work went rapidly. Several men brought tools.

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the most encouraging things that happened that afternoon while the railings were being installed, was the conviviality that emerged between Tonio and some of the other children present. To escape from the hot sun, Tonio had sat on the curb in the shady eastern side of the schoolhouse. At first he was there alone. But soon some of his classmates and other children—perhaps remembering the lessons on inclusion they’d learned in the Child-to-Child activities a few days before—sat down beside him in a friendly way. Before long, they looked like a group of young buddies, sitting together and talking whatever came into their heads. Tonio was actually speaking a few words, and smiling. It was big step forward from the withdrawn, totally silent niche he’d occupied just a few days before.

It is hard to know how things will be for Tonio. Life with muscular dystrophy is not easy. It entails the progressive decline of physical strength, with a loss of one physical ability after another until finally the lung muscles are so weak that breathing is compromised, as is the ability to cough. This often leads to pneumonia, followed by death, usually in the later teens or early 20s.

For all that, some people with muscular dystrophy or other seriously decapacitating or life-shortening disabilities, find ways to lead fulfilling and meaningful lives. In my book, Nothing About Us Without Us, Chapter 48,I relate a story about four siblings with muscular dystrophy who, even as they grew progressively weaker, were able to have adventurous lives. With their parents they helped to start and lead a program for other disabled children. In the process, they found a satisfaction, a sense of worth, and a degree of joy far beyond that of many people who are essentially normal.

Let us hope that Tonio continues to come out of his shell, to interact more confidently with his classmates and other people, and to gain the understanding, motivation and skills he needs to lead his life—for however long it lasts—with his fair share of satisfaction, loving relationships, and joy. Hopefully the growing awareness of his classmates, and their efforts to include him and to make his schooling more accessible, will help him on his way.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |