From a Snakebite to Children’s wheelchairs: Going Full Circle

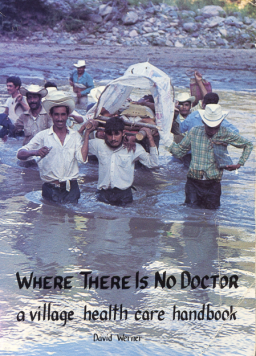

When I first wrote Donde No Hay Doctor (the original Spanish edition of Where There is No Doctor) in the early 1970s, I didn’t dream the village healthcare handbook would ever be used outside the remote reaches of Mexico’s Sierra Madre, where the villagers and I had set up a backwoods health program. Indeed, I’d drafted it in the local Spanish idiom with its stippling of indigenous and mestizo terms. (This was the only Spanish I knew, having never studied the language in school). I never imagined the book would eventually be translated into more than 90 languages, or be acclaimed by the World Health Organization as “arguably the most widely used community healthcare manual in the world.”

|

|

|

Certainly the handbook—and some of the other manuals and writings that have grown out or the “struggle for health” in the Sierra Madre—have been used far and wide. Over the years we’ve had some wonderful and unexpected feedback. In this newsletter I’d like to share examples of the kind of feedback we get, and relate how some of the ideas and methods we explored have been picked up and adapted in other places and circumstances. At times it seems like distant pieces of a puzzle, or segments of a circle, serendipitously falling together in weird and wondrous ways. The following example traces back all the way to my adolescence!

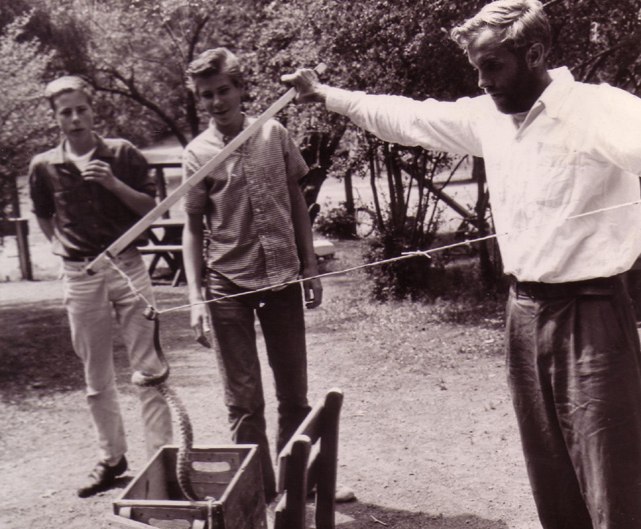

For some time now I’ve been working on an autobiography of sorts: a collection of stories I’d like to leave behind. This last summer I was writing about the time, back in the early 1950s, when I was bit by a rattlesnake. I and another teacher from the Peninsula School in Menlo Park, California, were taking a group of children on a natural history field trip on Mount Hamilton. In the forest we discovered a handsome Pacific rattlesnake. As I was teaching the kids how to catch and safely handle a poisonous snake, it bit me. Complicated by a series of errors—first by myself and then by the hospital in San Jose—the snakebite nearly cost me my life. I am convinced that what saved me was the use of cryotherapy: the application of ice packs to the snake-bit extremity.

At the hospital, no effective treatment was provided until I suggested the use of cryotherapy (ice packs). During my first three hours in the emergency room I’d been going from bad to worse. The only pit-viper antivenin on hand was three years expired. And to extract the poison from the bite, the only suction device available was a breast pump—which was useless, since the bite was on my thumb. The nurse’s attempts to wrap the breast pump around my thumb only served to massage the venom more quickly up my arm. Likewise, other measures the doctors took were of little help. The severe swelling in my hand was advancing up my arm, accompanied by a burning sensation, as if my arm were immersed in boiling water. When my lips and my other hand began to tingle, I knew I was in big trouble. Worst of all was the dizzying, painful pressure in my head, which felt like it was being crushed in a steadily closing vise. Such was my plight when I begged the doctors to pack my hand in ice.

I had first learned about cryotherapy for snakebite in 1953. Fresh out of high school, a friend and I made a six-month-long biological expedition to the wilderness areas of western Mexico. Before setting out, we made arrangements with several zoologists and botanists to collect specimens of the different plants and creatures they specialized in, ranging from flies, to grasshoppers and crickets, to lizards, to cacti.

The specialist for whom we collected live scorpions, was Dr. Herbert Stahnke, a toxicologist at University of Arizona in Phoenix. Dr. Stahnke was doing pioneering research on the development of a polyvalent antivenin for scorpion sting. For this he needed a large variety of living scorpions, and we did our best to meet his needs. In the process we became friends.

Dr. Stahnke was also doing groundbreaking research in treatment of snakebite. Through controlled studies with dogs, he discovered that one of the most effective treatments for snake-venom poisoning was cryotherapy. Not only did application of cold greatly reduce mortality rates, but it also significantly lowered the incidence and degree of local tissue damage (necrosis). Dr. Stahnke had published his findings in medical journals, yet had never managed to convince the medical establishment of the value of cryotherapy for treating snakebite.

When, in the San Jose hospital, I urged the doctors to use cryotherapy for my snakebite, they were at first reluctant. But when I told them about Dr. Stahnke’s extensive research and published papers, they agreed to give it a try. A nurse packed my hand and arm in crushed ice, taking care to keep the ice in a plastic bag wrapped in a towel, so as to prevent direct contact of ice and skin.

The results of ice treatment were quick and impressive. Within five or six minutes the burning pain in my hand and arm began to subside, and within a few more minutes the crushing pressure in my head diminished. In 15 minutes or so I felt almost normal, except for fatigue.

But then, as a few more minutes past, I began to feel a new kind of discomfort. My chilled hand and arm began to ache from the cold, and the aching gradually increased. So I asked the nurse to remove the ice for a while—which she did. The aching from the cold subsided fairly quickly and again, and for several minutes I felt relatively comfortable. But then, gradually, the burning sensation began to reappear, along with the feeling of pressure in my head. So I asked the nurse to reapply the ice packs. She did so. And as before, the burning and pressure soon subsided.

The doctors were so impressed with my stabilization that they transferred me from Emergency to a regular ward, with instructions that the ice packs be continued intermittently, at my request. Thus the cryotherapy was continued, on and off, throughout the night and into the next morning—during which time I felt relatively comfortable.

Toward noon of that next day, however, for some reason the cryotherapy was discontinued. After the ice was removed for the last time, within a few minutes, as usual, the burning sensation began to return. But when I asked the nurse to reapply the ice packs, she refused, saying that she no longer had the doctor’s orders to do so.

It was then that my most dire distress began. The flame-like sensation extending up my arm grew more and more intense. With it came intense swelling, which gradually spread up my arm and through the whole upper half of my body. The vise-like pressure intensified in my head, which felt on the verge of exploding like an overripe pumpkin.

My mind became progressively fuzzier. From midafternoon until the following morning I can remember almost nothing. That next morning I recall lying on my bed, totally incapacitated: unable to move, to speak, or even open my eyes. The burning pain in my upper body and pressure in my head were still there, excruciating yet somehow strangely distant, as if my body were someone else’s. Vaguely I heard the voices of a group of doctors around my bed, discussing the gravity of my condition and my odds to live or die. I wanted desperately to tell them to put back the ice packs. But I could say nothing. They thought I was in a coma.

For all I know, I may have been comatose part of the time. Of whatever happened the next couple of days, I have very little memory. But finally, on the fourth or fifth day, I slowly began to improve. The swelling and pain subsided. By the 10th day I was released from hospital.

This experience, coupled with my knowledge of Dr. Stahnke’s research, made me realize the lifesaving potential of cryotherapy for venomous snakebite. Years later, in our community-based health program in Mexico’s Sierra Madre, we began to use cryotherapy in the treatment of snakebite (often without antivenin, because of its high price) with remarkably good results. Even with bites of the very dangerous Mexican diamondback rattlesnake, if ice-treatment was begun early, not only were there almost no deaths, but swelling and pain were minimalized. Furthermore, with the ice there was virtually no local necrosis (tissue destruction from the venom), which is a very common and serious complication with bites of the diamondback.

The Secret to Success with Cryotherapy

The secret to optimal outcome with cryotherapy for snakebite, I believe, is that the ice packs are applied and removed ON DEMAND. It is the snake-bit person, guided by his or her subjective feelings, who should decide when the ice should be put on, removed, and put back on again.

Unfortunately, established protocol of Western medicine does not recommend cryotherapy for snakebite, but strongly warns against it. It is contraindicated say the textbooks, because of the high risk of severe tissue-damage from the ice.

I suspect that this reported “high risk of tissue-damage” from ice-treatment comes largely from the ingrained preference of doctors to be in complete control—especially where iatrogenic risk is concerned. Typically, they prefer to give standing orders, written on a chart, mandating—in this case—when to apply and remove the ice. The option of letting the “patient” govern, subjectively, when to place and remove the ice, would give the crucial decision-making control to the sick person rather than the physician. In effect, it redistributes and equalizes decision-making power. The healthcare provider and recipient become partners in the problem-solving process.

This equitable sharing of know-how, enabling people to care for their own and one another’s health is, of course, the underlying philosophy (and politics) of Where There is No Doctor.

Fortuitous Contact with the Viper Institute

This summer, as I was writing the story of my snakebite for my autobiography, I couldn’t remember how to spell Dr. Stahnke’s name. I wanted it to credit him and his research for quite possibly saving my life. So I did a Google-search on names like “Stonkey”—but came up with nothing. Then, on the off-chance, I typed in “scorpion antivenin.” This came up with an antivenon research project at the so-called “Viper Institute” at the University of Arizona in Tucson. I sent an e-mail to the contact address.

Next morning I got a return e-mail from the Viper Institute director, Dr. Leslie Boyer, which began:

Good morning, David!

It is a true pleasure to meet you. I once gave a copy of Donde No Hay Doctor to a gold miner in rural Chihuahua, and the resulting conversation influenced my career in a way that I can still feel, 20 years later.

It turns out that Dr. Boyer was indeed familiar with Dr. Herbert Stahnke’s work, and had the greatest respect for him. He figures prominently in a recent paper she has written on “A History of Scorpion Antivenom.” When she learned I’d known and collected scorpions for Dr. Stahnke 62 years ago, she was eager to compare notes. This led to a friendly exchange of e-mails, phone calls, and Skype conversations, which is still ongoing.

In one of these exchanges I asked Leslie Boyer to tell me about the gold miner in rural Chihuahua and how her offer to give him Donde No Hay Doctor had so dramatically influenced her career.

She told me that 20 years ago, as a young doctor, she had made a number of trips to impoverished rural communities in Mexico to help out with health needs. On these trips she always took copies of Donde No Hay Doctor to give to people.

One time, in a remote village in the state of Chihuahua, she offered a copy of the book to an elderly gold miner. However the gold miner said he already had one. He went into his hut and returned with a dogeared copy of Donde. He said he and his family had used it for all kinds of health problems — usually with good results. But there was one time he wasn’t so sure about, when his wife was very sick. He wanted to ask Leslie, as a doctor, if he had done the right thing.

He told Dr. Boyer the details. His wife had developed a bad cough with a high fever and difficulty breathing. He’d thumbed through the pages of Donde and found that she probably had pulmonia (pneumonia). It said to give penicillin. So he did.

“But how could you get penicillin way back here in the boondocks?” asked Leslie.

The miner told her that when they’d first got their copy of Donde No Hay Doctor, paging through it they saw it strongly recommended that every family have a basic kit of essential and potentially lifesaving medicines. So on their next trip to the city, he purchased the list of recommended medicines. So when his wife was so ill, he rummaged through the kit. And sure enough, there was a bottle of penicillin pills. So he gave them to his wife, as directed.

“And did the penicillin work?” asked Dr. Boyer.

“No,” said the miner. “She just kept on coughing and struggling to breathe.”

“But she obviously survived,” said Dr. Leslie, pointing to his wife preparing tortillas in the outdoor kitchen.

Yes, said the miner, but by the will of God. When he gave the penicillin to his wife it did nothing, he explained. She just kept on coughing and struggling to breathe. She didn’t begin to get better until the day after she began to take the pills.

“What that miner told me, about how he cured his wife’s pneumonia with a simple handbook and no professional help,” said Dr. Boyer, “gave me a whole new insight on health and healing.” She’d discovered the potential of ordinary people for self-care, especially when provided with basic information presented in a clear, accessible manner.

I loved Dr. Boyer’s story of the gold miner. What especially delighted me was the fact that his family had actually heeded the book’s recommendation to assemble a basic kit for medical emergencies. Having such a kit on hand, in this case, was probably lifesaving.

I also enjoyed learning how the gold miner’s story had influenced Dr. Boyer’s career. She had become dedicated to helping poor and isolated families have access to potentially lifesaving information and medicines, when and where they’re needed. For many years her particular focus has been the treatment of scorpion sting, especially in young children, for whom mortality rates are much higher.

The Battle to Make Antivenin Available

In her recent article, “History of scorpion antivenom: one Arizonan’s view,” Dr. Boyer explains what a long, frustrating, uphill battle it has been to get antivenin to those who need it, at an affordable price. In Arizona hundreds of children are stung by scorpions every year, and even today a significant number die for lack of timely, adequate treatment.

Even though effective antivenin was readily available decades ago in Mexico, access in the U.S. has been obstructed for a long time by the Food and Drug Administration, which has made testing and licensing requirements so exhaustive and expensive that only Big Pharma can comply. The big pharmaceutical companies tend to drag their heels in making potentially lifesaving products with a limited market potential available. And when they do so, the price tends to be prohibitive. Partly because the market for scorpion antivenin is relatively small, there has been a long delay in getting lifesaving antivenin to children stung by scorpions—especially in out-of-the-way places.

In Mexico, where scorpions are ubiquitous and people are often stung, an effective antivenin was made available at a reasonable price long before this was so in the United States. Yet importation into the U.S. was for decades prohibited by federal law. For many years—and still, to some extent—children in Arizona and New Mexico have died because of the lack of an available, affordable serum.

For decades, hospitals and health services in Arizona tried to arrange for legal importation from Mexico of the widely used antivenin, called Anti-alacran—mostly to no avail.

A Disobedient Monk to the Rescue

Fortunately, for scores children whose lives were in danger from scorpion sting, a Franciscan monk named Emmett McLoughlin committed civil disobedience. After seeing a child die for lack of antivenin, Father Emmett begun to work with Herbert Stahnke. He wanted to make sure that children stung by scorpions got the medicine they needed, even if that meant breaking the law. For years Father Emmett smuggled substantial quantities of Anti-alacran across the Mexican-U.S. border, hiding it in the ample sleeves of his robe.

Eventually Father Emmett was caught. His benevolent delinquency hit the local press, erupting a heated debate. An article in Saga magazine titled “Arizona’s mercy smugglers,” said:

… question was: whether to observe the law or break it and save children bitten by the deadly scorpion. Which deserves first consideration—human life or red tape?

The Franciscan hierarchy responded to the monk’s defiance of rules by ordering him to leave Arizona for another venue. Instead, Father Emmett left the priesthood—to keep his commitment to the health and rights of the poor.

Over the years, Dr. Stahnke succeeded in developing a highly functional scorpion antiserum. However the costs and exhaustive FDA requirements for getting it approved were so great that for years Stahnke and Arizona State University continued to provide it unofficially, free of charge, in emergency cases. Many years went by before, at long last, an FDA-approved scorpion antiserum was on the U.S. market. But even today, as Dr. Boyer points out, the high prices of the Big Pharma antivenins, along with periodic shortages, means at times inavailability when the lives of scorpion-stung children hang in balance.

Possible Reassessment of Cryotherapy

One outcome of my fortuitous encounter with Dr. Leslie Boyer has been to spur her interest in the possibilities of cryotherapy for snakebite. As a toxicologist who is familiar with Dr. Stahnke’s research, and as director of the Viper Institute at Arizona State University, she is an excellent position to re-investigate the therapeutic advantages of cryotherapy for snakebite, and demonstrate its relative safety when ice is applied and removed on an on-demand basis. If the merits of on-demand cryotherapy can be scientifically confirmed, and the treatment restored as medical protocol, it could make a big difference both to survival rates and to prevention of necrosis in venomous snakebite.

Medical dogma is recalcitrant to change, but change it must for the art of medicine to evolve.

Friends in Common: the New Wheelchair Program in Nogales

In my conversations with Dr. Leslie Boyer of the Viper Project in Tucson, she asked what projects I was currently active in. Among other things, I told her about the wheelchair workshop in Duranguito, Sinaloa, Mexico, where a team of disabled persons makes custom-designed wheelchairs for disabled children. On hearing this, Dr. Boyer asked if by any chance I knew Dr. Burris Duncan in Phoenix, Arizona.

I told her yes. For years I have been in communication with Burris—better known as Duke—about the fledgling community-based disability equipment program he started in Nogales, Mexico.

Indeed, the Nogales program—called ARSOBO (for ARizona SOnora BOrder)—was to some extent modeled after the PROJIMO programs in Sinaloa, Mexico, with which I have been deeply involved. (“PROJIMO” in Spanish stands for “Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico.”) Not only was ARSOBO to a large extent inspired by the PROJIMO wheelchair workshop in Duranguito, Sinaloa, but ARSOBO’s master wheelchair builder is Gabriel Zepeda, a paraplegic craftsperson who for years was director of the PROJIMO Duranguito wheelchair shop.

“But how do you know Duke Duncan?” I asked Dr. Boyer, astounded she knew of the Nogales program.

She told me that long ago when she was in high school, she had joined Amigos de las Americas, a youth service program in which teenage volunteers from the U.S. spend their summer vacation somewhere in Latin America, where they live with a local family and help out in a community health or development project. As it happened, she told me, Leslie Boyer’s counselor for her Amigos summer project in Honduras was none other than Duke Duncan. Indeed it was Dr. Duncan who had introduced Leslie and the other volunteers to my book Donde No Hay Doctor. … Small world!

As chance would have it, this November, 2015 — just a few weeks after Dr. Boyer and I began to communicate—at the invitation of Duke and Gabriel Duke, I had a trip planned to visit ARSOBO. I would be accompanied by two wheelchair builders from PROJIMO Duranguito. So plans were made for Dr. Boyer and a group of her students from Tucson to come meet with us there in Nogales.

Serendipitously, this whole chain of events began because I didn’t know how to spell Dr. Stahnke’s name!

In our next newsletter we will give an account of our recent visit to ARSOBO in Nogales, and the wheelchair workshop there run by Gabriel Zepeda, the original leader of the PROJIMO children’s wheelchair workshop in Duranguito, Sinaloa, with which HealthWrights is closely involved.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |