Serendipitous Connections: A Boy with CMT Muscular Atrophy—Same as Me

Three years ago, in 2013, I received an urgent email from a mother in Guadalajara, asking me if I knew anything about Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome. She told me her son, Tomás—born in July, 2003—had been diagnosed with CMT, a progressive neurological condition beginning in early childhood. At birth he’d seemed normal. But hadn’t begun to walk until he was two-years-seven-months old. When he finally started walking, he had a strange wobbly gait with poor balance and frequent falls. As he grew, the awkward gait gradually became more pronounced, with notable weakness in his feet and lower legs. Weakness in his hands and fingers likewise became apparent, causing difficulty with fine manual skills.

His parents had taken him to one specialist after another, trying to learn more about his disability, and what to do about it. They took him to the best private neurologist in the city, who ordered an electrodiagnostic study and announced to the family that

The study was abnormal with electophysiological signs compatible with sensorial and motor polyneuropathy with demyelinating characteristics.

“It was as if they were talking another language,” the boy’s mother, Lupita,” wrote. “We didn’t understand.”

Later they took Tomás to a pediatric neurologist at the Centro Médico Occidental in Guadalajara, who told them, in brief, that “for this illness there in no medicine nor surgery—not here nor in China.” When Lupita pointed out that her son fell a lot and she was afraid he’d hurt himself, the doctor said, “Buy him a walker or something.”

Tomás’s parents searched far and wide to find out more about CMT and what to do about it, but came up with very little helpful information. Many doctors and therapists had not even heard of Charcot-Marie-Tooth.

One of the pediatricians that Lupita consulted recommended she look in my book, El Niño Campesino Deshabilitado (Disabled Village Children). She tracked down the book online and found a short reference to CMT, and a number of practical ideas for children with muscle loss. She decided to contact me by email.

In her email, Lupita asked me if I had any experience with CMT. When I wrote back saying I had a lifetime of experience with CMT, given that I had the syndrome myself, she was astounded. Talk about serendipity!

That was the beginning of a long period of lively communication and sharing, which now spans more than three years.

Child-to-Child Activities Facilitated by Tomás’s Mother

For me, one of the most heartening outcomes of our online interchange with Tomás’s mother, Lupita, was the action she took to increase the understanding and inclusiveness of his classmates in school.

This last year Tomás began secondaria (equivalent of junior high school). At first a number of the students were cruel to him, making fun of the way he walked. They nicknamed him “patas-chuecas” (cripple-paws), “el zombi,” and “pinguino.” (On learning this, I told Tomás and his mother I’d been similarly teased as a child; my schoolmates nicknamed me “the duck” and waddled in a line behind me chanting “Quack, quack, quack.” I know just how much such playful teasing can hurt.)

When Lupita described how her son Tomás was being made fun of at school, I told her how in Mexico—and in workshops I’ve facilitated in various countries—we’ve used Child-to-Child activities to sensitize schoolchildren to the needs and possibilities of children who are “different.” I referred her to the chapters on Child-to-Child in my books Helping Health Workers Learn, Disabled Village Children, and Nothing About Us Without Us, all freely accessible online in Spanish.

Find the chapters on Child-to-Child and insert here

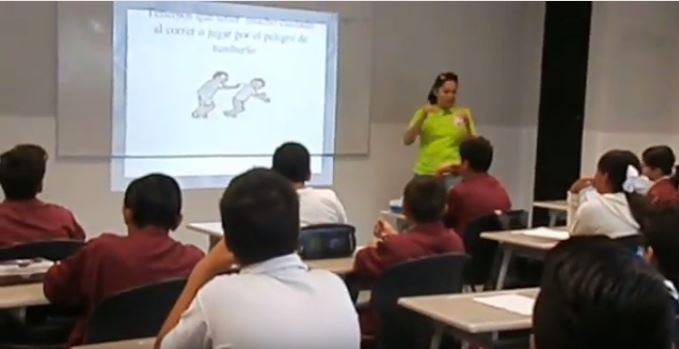

Following up on this, Tomás’s mother arranged with the director of the school to lead a number of Child-to-Child activities in her son’s classroom. First she presented the class with a PowerPoint show she put together about Charcot-Marie-Tooth, how it weakens muscles of the feet and hands, and the functional difficulties this causes. To help his class actually experience these difficulties, she introduced several simulation activities:

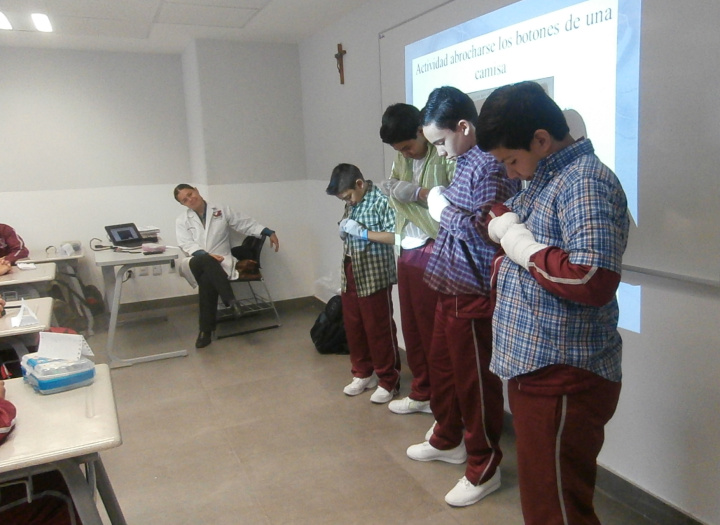

Understanding the Reduction of Manual Dexterity

To understand the reduction of manual dexterity, she asked student volunteers to put stockings on their hands, and then try to button their shirts. They compared the time it took to button a shirt with and without stockings on their hands.

Likewise the children tried to pick up coins from the floor with their stocking-covered hands.

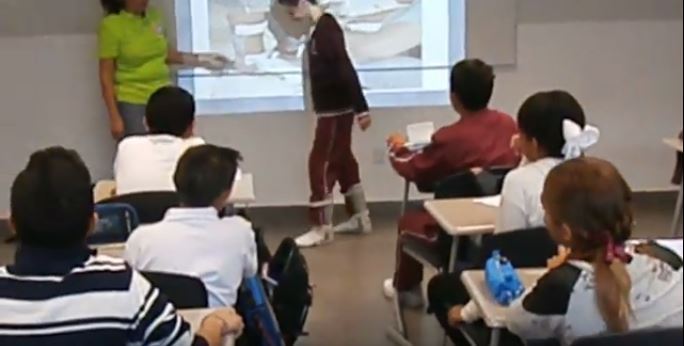

Understanding the Difficulty of Walking with Weakened Feet

To understand the difficulty of walking with weakened feet, volunteers took turns putting on plastic leg braces (ankle-foot-orthoses, or AFOs) and tried to walk with them.

With the leg braces this boy stumbled, flounded and sometimes fell. By comparison, even with his inadequate braces, Tomás’s strange gait was far more efficient, and the students’ appreciation of both his challenges and his achievements grew considerably.

Therapy and Orthopedic Devices—a Mixed Blessing

In their search for ways to help Tomás cope with his CMT-related challenges, his parents took him to a range of physical and occupational therapists. The program that has welcomed him most ambitiously has been national Centro de Rehabilitación Infantil Teletón (CRIT) better known as “el TELETÓN.”

For years Tomás’s parents have taken him dutifully, twice a week, to Teletón’s luxurious therapy center. Because he is so charismatic and photogenic, Tomás has become one of Teletón’s star patients. He has repeatedly been filmed and interviewed on the program’s televised fundraising campaigns. In the process, Tomás has gained a winning stage presence and an ability to speak with ease about his disability and challenges—praising the great help Teletón has been to him.

Psychologically, the friendly staff at Teletón have certainly given a boost to Tomás’s self-esteem and his ability to talk about his disability with ease. This can be observed on a number of CRIT videos posted on YouTube. Provide links?

In terms of physical benefits derived from Teletón, however, results have been mixed. He may get some benefit from the physiotherapy—though much of it appears to be routine exercises which, though carried out with lots of colorful and costly equipment, do not always address his specific muscular-atrophy related needs.

In terms of orthopedic appliances, the orthopedic appliances that Tomás has been fitted through Teletón have consistently been inadequate, or even counterproductive. All three pairs of these AFOs (ankle-foot-orthoses), though custom-made, have turned out painful to use and have made his walking more cumbersome and insecure, rather than improve it.

The two major problems with these custom-molded polypropylene braces were both obvious and easily preventable:

-

Painful pressure over protruding bones. In molding the plastic to the shape of the foot, adequate allowance had not been made to accommodate bony prominences (such as anklebones), thereby causing pain and eventually pressure sores. Such damaging points of pressure can:

-

a) be prevented before the AFO is molded over a plaster cast of the foot, by building up the plaster slightly over the bony prominences before the hot plastic is stretched over the cast, or

-

b) be corrected: either by putting doughnut-like padding around the pressure point, or by heating the plastic over the pressure point and then stretching the heat-softened plastic to form a dent or shallow pit in order to accommodate the bony prominence.

-

-

Foot-part of brace too long. The plastic under the sole of the foot extends stiffly beyond the end of the toes. This tends to make walking much more awkward, leading to tripping and falls. For most people, the AFO should end at the base of the toes. This allows the toes to bend up at the end of each step, for a smoother, more natural gait.

Although both of these problems are easily observed and preventable, Teletón is not alone in routinely allowing them to occur. Over the years I have visited dozens of rehab programs in different countries, and estimate that over half the custom-molded plastic leg braces I’ve seen have been inadequate or painful—often because of either or both of the two problems mentioned above.

To PROJIMO for Braces

For the last three years I have been corresponding with Tomás’s mother Lupita about her son’s challenges with Charcot-Marie-Tooth. She has sent me videos that she and her husband took of the Child-to-Child activities she facilitated, of the therapy he has received, and of his birthday parties and other key moments in his life.

Ongoing Issues with Tomás’s Braces

Last May, Lupita wrote me again about her son’s problems with his braces. Through Teleton, he had again been fitted with AFOs, this time so painful that he refused to wear them. This led to an argument between Lupita and her husband, Juan. She pointed out that the braces were professionally made and felt that Tomás should get used to them, even if they hurt him at first. His father Juan felt the boy’s complaints should be taken seriously, and that he should not be forced to use them. In the end the parents agreed to have a new pair of braces made by a different orthoptist.

But alas, the new AFOs were no better. Lupita wrote to me at a loss as to what to do: whether to make her son wear them or not. Now he was rebelling and flatly refused.

I asked Lupita to make a video of Tomás walking: with the braces and without. A few days later she sent me the video. Without question, the boy walked better—more smoothly and less erratically—without the braces. And as before, the new braces extended stiffly beyond the end of his toes, causing him to stumble and lose his balance.

Tomás Goes to PROJIMO Coyotitán

In view of these problems, I invited his parents to bring Tomás to PROJIMO, in Coyotitán, Sinaloa, to see if the local team of disabled crafts-persons there could make him braces that would be comfortable and help him walk better.

PROJIMO is the Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) program, run by disabled villagers, which grew out of the village health program in the Sierra Madre that I helped start 50 years ago. The village of Coyotitán is over 300 miles north of Guadalajara—a long trip. But if it meant helping Tomás to walk better, and perhaps slow down the progression of deformities, it would be worth it. I made the family no promises that the braces would be successful, but I told Lupita we would do our very best.

The family agreed to come. They bought new tires for their tiny, four-cylinder car and on Sunday, May 8, 2016, drove from Guadalajara to my home in el Tablón, Sinaloa, south of Mazatlán. The next morning we left at the crack of dawn for Coyotitán, arriving just as the workshop was opened for the new work-week. That way, we hoped that in five days Tomás’s new braces could be completed, allowing the last couple of days for ample trials and adjustments.

I agreed to spend the full week in Coyotitán while Tomás’s braces were being made, to help out with the design and fitting. But I had an additional motive to spend those days in Coyotitán. Two months before, I had corrective surgery on my left foot—a triple arthrodesis (fusion of the bones in mid-foot — and my foot was still in a cast. So while the disabled rehab workers in PROJIMO were making Tomás’s new braces, they could also make a new brace for my own, recently operated foot.

PROJIMO Coyotitán: Disabled Service-Providers Serving the Disabled

The week that that Tomás, his parents, and I spent at PROJIMO Coyotitán was a wonderful and eye-opening experience for all involved. At first it seemed that the specially fitted braces needed for Tomás and for me might not be possible to make there. PROJIMO’s experienced brace-maker— Armando Nevarez—who has been working with the program for 35 years, is on a six-month leave, helping to train brace-makers in the new community rehab program called ARSOBO, in Nogales (see Newsletter 78). The acting brace-maker, named Santa Ana, is a partially-paralyzed middle-aged man who came to PROJIMO a couple of years ago for his own rehabilitation, and later returned to apprentice in brace-making. While he knew the basic steps of making plastic AFOs, he still had very limited experiences in evaluating individual needs and making the appropriate modifications. Fortunately, however, I had a lot of experience in the latter, and as it turned out the two of us made a good team. Also Inez, another long-time disabled worker at PROJIMO, assisted with the casting and draping of the plastic over the plaster casts of our feet.

Discovering Unrealized Abilities

Altogether, a lot of the workers in the multipurpose workshop (where orthotics, prosthetics, and wheelchairs are made) pitched in and helped, in a very cheerful and inclusive way. The fact that all of this motley team of rehabilitation workers were themselves physically disabled—and yet performed a wide range of technical skills with remarkable ability—was a revelation to both Tomás and his parents. Indeed it changed their vision of what was possible for the youngster.

While Tomás’s parents are very supportive of their son, and encourage him to do a lot of things, when it comes to physical activities, they tend to be over-protective. They are fearful of his falling and getting hurt. And they do things for him they are afraid he can’t do for himself.

For example, tying his shoes. His parents realize that with muscular atrophy in Tomás’ hands, his fine motor skills are compromised. Convinced that he cannot tie his own shoes, they have always done it for him. And Tomás— now almost 13 years old— has never learned to do it.

In the workshop, when I was trying the new brace on my operated foot, I bent down to tie my own shoe. For me it isn’t all that easy. The atrophy in my hands is far more advanced than in Tomás’s hands, and I have no strength for opposition of my thumbs. But I have figured out tricks to tie my shoestrings in a bowknot.

“Do you mean to say you can tie your own shoes?!” exclaimed Tomás’s parents. “Look Tomás! David can tie his own shoes!”

Various workers in the shop helped Tomás learn new skills that neither he nor his parents had dreamed possible for him. Taking the lead in this was Adán, an amputee whose jobs include repairing shoes. Adán was especially friendly to Tomás, and the boy spent a lot of time talking with him and watching him work. He was fascinated with art of shoe repair, and the precision with which Adán worked. One time when Adán was replacing the torn tongue of a shoe with a new one Tomás bent over closely to watch. To where the tongue would be attached to the shoe, Adán first made a series of tiny holes to guide needle and thread, and then very carefully began to pass the thread through the holes with a needle.

“You’re so exact, the way you sew in that tongue!” said Tomás admiringly.

“Want to try?” smiled Adán, holding the needle out to him.

“Me?” stammered the boy. “I couldn´t begin to ….

“It’s real easy,” encouraged Adán. “Just poke the needle through the holes and pull the thread through. Give it a go!”

Gingerly Tomás took hold of the needle as best he could, and thread it through the holes that Adán carefully lined up. A moment later, with a new sense of confidence, the boy was busily stitching the tongue into the shoe.

“Perfect!” exclaimed Adán. “See how nice it looks.”

Tomás was grinning like a Cheshire cat. His parents, who had been watching, were amazed.

“If you like you can come spend your summer vacation here in PROJIMO,” said Adán. “We can teach you all kinds of useful skills.”

Falling in Love with a Hand-Cranked Tricycle

While Tomás was waiting for his braces to be made, he found lots of exciting new things to do at PROJIMO. But his biggest infatuation was with a hand-powered tricycle. Different models of these tricycles are made in the wheelchair shop, and a number of the disabled workers use them to get around, in preference to wheelchairs. The large front wheel and hand-powered lever make them faster and more easy to navigate on rough terrain than a typical wheelchair.

There were a couple of these tricycles sitting in the patio in front of the workshop, and before anyone noticed, Tomás scrambled onto one and began experimenting with how to make it go.

Before long he was careening around the playground in sheer delight. Quickly Tomás made friends with some of the local boys, and would accompany them around the village—they on their bikes and he on his beloved trike. He poured sweat in the hot pre-summer weather, but he never seemed to tire.

Tomás’s father, Juan, was equally thrilled to see his son so ably and avidly riding the trike. Juan has a passion for bicycling, and at home in Guadalajara every day he pedals 20 to 30 kilometers: on errands, for exercise, and primarily for fun. Over and again he has tried to teach his boy to ride a bike. And Tomás has been eager to learn. But his weak, floppy ankles, just won’t stay on the pedals. His father—who is an engineer by training—has improvised all kinds of devices to keep Tomás’s feet on the pedals, yet allow him to remove them quickly when necessary. But so far nothing has worked.

So Juan also fell in love with the tricycle—and has talked to Inez—who had polio as a child and uses one himself — about making one for his son.

Conclusion: Self Help

One of the nice things about PROJIMO, with its team of disabled crafts-persons, is its friendliness and inclusion of other disabled persons and their family members as peers and as equals. Just as Tomás began to help Adán with shoemaking, Tomás’s father, Juan—an engineer by trade and very handy with his hands—began helping out in the workshop, first with his son’s braces, then with mine, and then in anything where his assistance and skills could be useful. By the end of their week in at program, a strong camaraderie had developed between the PROJIMO team and the family.

To get Tomás’s PROJIMO-made AFOs so that the fit him comfortably and allowed him to walk better, a lot of modifications and adjustments were necessary. I played a leading role in this, based on my long experience with fitting braces to my own feet—which have similar problems and needs to those of Tomás, since we both have the same disability. What I found especially encouraging was that Juan, with his engineering skills and dexterity, picked up ideas very quickly, and sometimes was taking the lead in figuring out adaptations himself to improve his son’s braces. That way, when they are back in Guadalajara, I knew that father and son would take more initiative and innovation in meeting the boy´s special needs.

But for Tomás and his parents, their week at PROJIMO, resulted in far more than more useful orthopedic appliances. It opened up doorways to new possibilities and higher expectations for the future. For the family, the opportunity to see and interact with a team of disabled people who provide exceptional services, and who do so in such a cheerful and inclusive way, was truly empowering. And for them to get to know and see in action an 81-year-old man the same atrophic syndrome as the boy has, let them know that having such a disability is not the end of the world.

For me, too, their visit was a joyful adventure, with deep satisfaction in being able to befriend and assist a youngster with the same disability I have, and to bond with him and his family.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |