Health Services in a Land of Contradictions: Innovations in Thailand to Meet Health Needs of the Most Vulnerable

My invitation to Thailand

In May 2017 I was invited by Health and Share Foundation (HSF) in Thailand, and its parent organization, SHARE (based in Japan), to visit their innovative community outreach program in the Ubon-Rachathani province, on the Thai-Laos border. The purpose of my visit was to exchange ideas for “helping to enable the most vulnerable persons and groups” to better meet their pressing health-related needs.

Also, for the final day of my two week sojourn in Thailand, I was invited by the Faculty of Public Health at Mahadol University in Bangkok to speak at the international “Eighth Public Health Conference on Advancing Sustainable Development Goals, 2030,” to be attended by representatives from the 11 ASEAN (South-East Asian) countries, plus several others. I was asked to speak on “Health Security and Quality of Life of Outreach Populations.”

Thailand’s and Mexico’s Health-related Similarities and Dissimilarities

Mexico (where I have been involved with villagers’ well-being and rights for 50 years) and Thailand have a number of key characteristics in common, including underlying determinants of health. In recent decades both Thailand and Mexico have become “Middle Income Countries,” due in part to having become “free-market” economies highly dependent on multinational trade. (Thailand is now the world’s #1 exporter of rice). However, as their GDPs rise, both countries have experienced a mushrooming gap between rich and poor—in terms of wealth, health, and standard of living. Despite efforts by both nations to introduce policies of “Universal Health Coverage” (UHC), their living conditions, access to services, and quality-of-life have become increasingly unequal in different social strata and regions of the countries. Both nations have long histories of struggles between democratic and autocratic rule.

Both Mexico and Thailand have their roots in agriculture, and a long history of struggle over land tenure. Still today, in both countries, the best land is owned by wealthy land barons, while a multitude of tenant farmers barely scrape by. Seasonal (and permanent) migration to the burgeoning, heavily polluted capital cities has contributed to many problems—not least of all, the spread of HIV-AIDS.

Power and health in Thailand

Political Power in Thailand

Thailand’s power dynamics fluctuate between three imposing entities: monarchy, Buddhism, and the military. Historically the monarchy held supreme rule for many centuries. But in 1932 a move was made to “democratize” the nation by separating the royalty from politics, and by introducing a popularly elected parliament and prime minister. However in 1933 Thailand had its first military coup—followed by 18 more coups, the last two in the past three years. The latest coup, in 2016, occurred just before the death of the widely revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who during his 70-year reign had been a benevolent influence on the nation’s policies and public services. King Bhumibol died in October 2016 and was succeeded by his far less scrupulous son, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, whose then anticipated coronation is said to have precipitated the most recent coup.

The new military junta, along with the new king, have become increasingly authoritarian—so much so that the Thai people and the press take care not to criticize them too strongly in public. (I was warned that the driver of our government minibus might be listening to our conversations in order to report them to the authorities.) I asked if the present military regime might roll back some of the people-supportive health and welfare policies that had been introduced under King Bhumibol’s benevolent influence. I was assured that the current junta wouldn’t dare do so. The Universal Health Care program—which provides most medical services to all, free of charge—is so popular that if the ruling elite tried to dilute it, or reintroduce user-fees, the population would rise up in protest.

Thailand introduced its Universal Health Care program in 2001, long before most other low-or-middle-income nations, and has subsequently expanded its outreach and coverage. User fees were removed (for the most part) in 2006, and it is Thailand’s policy to provide complete—or close to complete—coverage even for highly expensive chronic maladies such as renal failure and HIV-AIDS.

Thailand’s Enterprising Steps to Combat HIV-AIDS and Other Chronic Diseases

The World Health Organization has lauded Thailand for having one of the world’s most comprehensive and successful programs in combating HIV-AIDS.

In terms of prevention, the Thai Health Ministry, in cooperation with other branches of government, has a multifaceted education program, with special focus on high-risk groups. Its policy is to make condoms freely and universally available, even to children in middle-school. Since Thailand traditionally has relatively open and permissive mores regarding sex, many children of 12 to 14 years of age begin experimenting, especially in rural areas.

With regard to treatment, the Ministry now makes HIV testing and anti-retroviral medication (ARV) freely available to all who need it. At least that’s the policy. But achieving full and sustained coverage isn’t easy. Many people who fear they may have HIV are afraid to let even family members know, or to go to clinics for testing and medication where someone might recognize them. So the Health Ministry has set up unmarked locations where people can get testing and meds clandestinely.

For similar reasons, early treatment and long-term compliance with medical recommendations are major challenges. Typically, people don’t go for testing until serious symptoms of AIDS-related infections develop. This may not happen for years, during which time the retrovirus is transmissible through sex—or via injected narcotics (another big problem). Likewise, when symptoms disappear through treatment many people stop taking their meds. This leads to a return of symptoms and renewed contagion. It also contributes to the emergence of new strains of HIV resistant to ARV medications—a rapidly growing and very worrisome problem.

To circumvent the deadly high price tag of ARVs produced by Big Pharma, Thailand courageously dared to develop and manufacture its own generic equivalents. Following the military coup of 2006, the incoming junta chose to violate international patent laws on several outrageously over-priced life-saving drugs. In order to achieve and sustain Universal Health Coverage, it declared it needed to put human need before transnational greed.

Despite threats from Big Pharma, which withdrew of some its R&D clinics, Thailand has succeeded in providing far-reaching medical coverage to the majority of its citizens with long-term treatment of chronic illnesses, including HIV-AIDS, heart-disease, diabetes, and renal failure. All at relatively low cost! Thailand spends about 4% of its GDP on health, compared to an average of more than 6% by most other middle-income nations. Escaping at least part of the profiteering of transnational drug companies has effectively saved millions of lives.

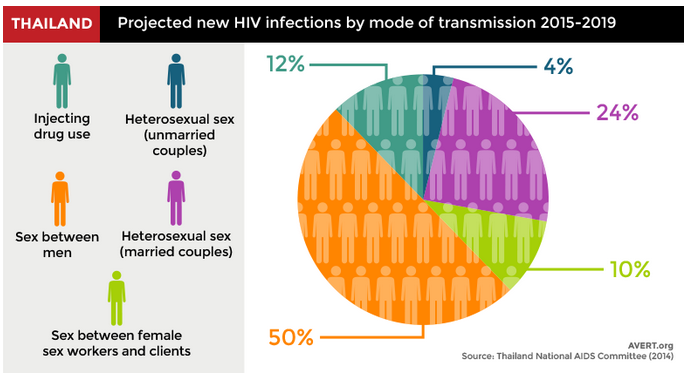

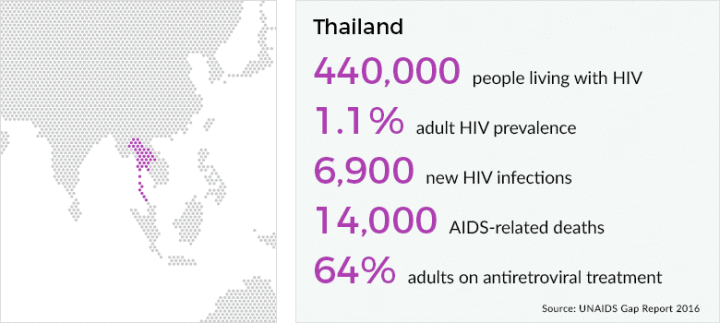

As of 2009, Thailand had the highest prevalence of HIV in Asia. The incidence of HIV-positivity is now about 1.1 percent of adults—down from almost double that a few year back.

The principle modes of transmission are shown in the graphs, above. Although the prevalence of HIV is falling, certain groups continue to become infected in especially high number. 10% of transmission is due to female sex workers and their clients.12% is through unclean needles by drug-users. Married couples (usually husband to wife) account of nearly 25% of the cases. But a remarkable 50% of new transmissions are among “MSM” (men who have sex with men). These include gay men, transgender persons, and male sex workers. By far the highest rate of prevalence is in transgender men.

AIDS in Thailand is primarily a disease of young people, including adolescents and, to a lesser degree, children. Most children with HIV contracted the virus from their mothers during childbirth. Fortunately, the incidence of “AIDS babies” has fallen dramatically in recent years—to under 2% of mothers who are HIV-positive—thanks to a coordinated action to assure that all pregnant women are tested for HIV, and, if necessary, treated.

A number of children, however, contract HIV from having sex with HIV-positive males. This is especially common among indigent migrant children coming from the poorer neighboring countries of Burma, Laos, and Cambodia. These children—of both sexes and occasionally as young as nine years old—will sometimes sell their services in exchange for a meal, a pittance, or a little love and kindness.

Thousands of sex-workers—mostly young women and adolescent girls but also men and boys—come across the border from the adjacent countries. To help control the spread of HIV-AIDS and other STIs (sexually transmitted infections), the Thai government now officially offers free medical treatment, including for HIV, to migrant workers—legal or illegal. (However, in parts of Thailand, some hospitals and clinics refuse to treat them.)

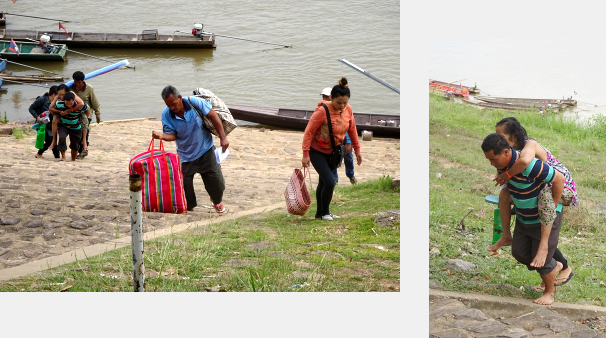

The district of the Khemarat where I visited is separated from Laos by the Mekong River (Me-kong means “Mother River”). Every day thousands of Laotians cross the river in small canoe-like water-taxies. Some are day laborers. Some are sellers of fruit or wares or illicit drugs. Some have nothing more to sell than their bodies.

And some Laotians cross over into Thailand for medical treatment. The closest hospital on the Laos side is nearly 100 km. away. At the Khemarat crossing, we watched a porter carry a sick woman on his back up the steep flight of more than 100 stone steps from the river up to the road, while her elderly husband trudged behind. At least at the Khemarat crossing, I was told, such ailing visitors are usually well received and freely treated at the District Hospital.

On entering Thailand, all that visiting Laotians, ill or otherwise, are required to do is write their nickname in a ledger, and on leaving, cross it out.

‘Health and SHARE’: Its Priorities and Programs

Although Health and Share is a small program, its impact may prove to be greater than might be expected. Any small innovative program that has demonstrated an ability to energize its workers, and produce real change, may serve as an example to other programs, and in this way have an effect that is disproportionate to its size. Health and Share Foundation works in close cooperation with government agencies, and is viewed as a test project. Insofar as its procedures are shown to be effective, they may be taken up by the government and integrated into its programs. Because of this relationship with government programs, Health and Share may have an even greater impact than most small innovative programs.

Evolving Priorities of the Health and Share Foundation

In the 1980s, when Share began working in community health in Eastern Thailand, its primary objective was to help villagers combat the most pernicious “diseases of poverty,” such as child diarrhea. Even today in most poor countries, diarrhea remains a major killer of young children. It kills mostly children who are seriously undernourished, or who have reduced immunity (as with AIDS). But currently in Thailand—except for the impoverished “hill tribe” communities in the north-east—surprisingly few children now die from diarrhea, though many still fall ill from it. This exceptionally low mortality from diarrhea appears to be an outcome of improved diet: most children in Thailand—even those from quite poor families — presently get enough to eat. The steep decline in child undernutrition is due, at least in part, to the government’s safety-net provisions to needy families. But it may also in part be due to the Buddhist tradition of “compassion or caring and sharing, whereby villages regularly donate food to the priest in the local temple, who in turn shares it with the hungry.

So it was that the villagers in Khemarat, where Health and Share Foundation (HSF) had started its community program, told the HSF team that diarrhea was no longer a major concern. They asked instead for help coping with HIV-AIDS—which had become a major and much feared problem. HIV now affects around 1.3 % of the Thai population—the highest national rate in Asia.

In response to the community’s expressed need, HSF changed its focus, making one of its top priorities the management of HIV-AIDS. They soon found this meant not only strategies of prevention, treatment, and support services, but also addressing the enormous fear of AIDS and prejudice against anyone who was HIV-positive or suspected of being so. In terms of fear and prejudice, in Thailand (as in many countries today) HIV-AIDS is the 21st century reincarnation of leprosy.

Since the stated mission of Health and Share Foundation is “to help the most vulnerable and marginalized improve their quality of life,” this new focus on HIV-AIDS certainly seemed to fit its calling.

Promotion of Peer Counselling in Coping with HIV-AIDS

Because of the large numbers Laotian sex workers crossing into Thailand, the border area of Ubon-Rachathani has become a hotspot for the spread of HIV-AIDS and other STIs. The Thai government makes free testing and treatment available to these sex workers, as well as free condoms. However, communications tend to be poor and many people, especially the sex workers, are fearful of seeking assistance. For this reason, the Health and Share Foundation team makes a special effort to reach out to the immigrant sex-workers. Since most sex-work is located in small semi-clandestine brothels run by enterprising pimps, the SHF staff have made amiable contact with the pimps. They have recruited most of the pimps in the 17 local “sex shops,” as well as some or the some of the senior, public-spirited sex-workers, to become local “linkage points.” These pimps and sex-workers provide condoms and health education, and facilitate the process whereby the sex-workers can be tested and treated for HIV-AIDS.

Fortunately the District Health Department is supportive of this initiative and cooperates closely with the HSF team. (Indeed, some of the directors and key players in the District Health program are members of the Health and Share Foundation advisory board.)

In Khemarat the local sex shops are permitted by the authorities to operate on a quasi-legal basis—which makes working with the pimps and sex-workers much easier. (For similar reasons there has been a debate about legalizing illicit drugs, so as to invest more in prevention and treatment than in punishment). Unfortunately, it is possible that the present military junta will outlaw existing “sex-shops,” thus forcing them underground, which would make the prevention and treatment linkages far more difficult to maintain, while doing little to reduce prostitution.

The Khemarat border area is, likewise, a hotspot for the sexual activity (commercial and otherwise) of men who have sex with men (MSM). It is within this MSM group that transmission of HIV-AIDS has been highest. Again, many MSM are inadequately informed of the opportunities for testing and treatment, or are reluctant to seek help. So Health and Share has established “linkage points,” in key locations, where kindly gay or transgender men serve as “peer counselors” for others—providing free condoms, advice, and information on prevention and treatment of HIV-AIDS and other STIs.

In the busy shopping area above the river crossing from Laos, my Health and Share guides introduced me to a good-natured, gentle middle-aged man whose small roadside kiosk served as a “linkage point” for other MSM. With us, he was very open and self-assured. He took pride in his volunteer role of helping others like himself find ways to have safer sex, and take steps to be tested and treated for STIs. His only complaint was that, at the present, he had run out of condoms. He requested that the supply chain be more reliable.

People Living with HIV-AIDS and Transgender Men—Bringing these Vulnerable Groups Together

Early in my visit to Khemarat, my friends at Health and Share Foundation took me to a district hospital to attend a “Self-Health Support Group” of People Living with HIV-AIDS (PLWHA ). The group—currently with about 60 participants—was started by HSF several years before but now is organized and managed completely by its members. The members are mostly young adults, though some are older people and children. The youngest is a nine-year-old-boy who had contracted HIV from his mother at birth.

One of the main purposes of this group is to help members gain a positive self-image and explore ways to improve one other’s quality of life. This is a big challenge in a society where people with HIV are often feared and shunned. What amazed me was that, despite the huge barriers they faced, nearly everyone in the group seemed positive and relatively happy. At least among themselves, they had achieved a sense of belonging and discovered joy in reaching out and helping one another. The older, more knowledgeable persons were especially caring in mentoring the younger and less well-adjusted members.

Another thing that amazed me is that the key leaders and facilitators of this HIV-positive group are persons who are openly transgender. (In Thailand the term transgender is used by persons who chose to keep their original genitals but dress and groom as the opposite sex. The term transsexual is used for those who surgically change their genitals.)

The principle facilitator HIV Self-health Group is a highly skilled, charismatic transgender individual nicknamed Cherry. Dressed modestly as a woman, she is not only beautiful, but radiant. Her boyfriend, who was also at the meeting, enthusiastically helped out in a number of ways. I found it heartening that the entire group not only fully accepted Cherry and her boyfriend, and the other transgender leaders, but clearly admired them for their abilities and compassion.

How refreshing! Here were two distinct groups of highly vulnerable, socially marginalized people—people living with HIV-AIDS and those of a gender minority—who have managed look beyond society’s prejudices and reach out lovingly to one another. This group of marginalized people was an example from whom we could all learn. I guess there’s nothing like being unfairly treated and spurned to open up one’s heart to the trials and suffering of others.

Although Cherry is HIV-positive, she appears in remarkably good health: physically, mentally, and socially. With daily retroviral treatment and regular testing, she lives an active, and fulfilling life. Her boyfriend remains HIV-negative. Cherry is completely honest and open both about being transgender and HIV-positive. She is an inspiring role model for anyone who has the cards stacked against them.

While Cherry is completely up front about being HIV-positive, most of the group’s members are not. In some cases even their families and friends are unaware of their status. People fear losing their jobs and their friends. So in order that its members feel safe about opening up at the meeting, the group has an understanding that what is said and shared at their meetings will be divulged to no one after they leave. Likewise photographs are strictly monitored and restricted. Some members, like Cherry, are willing to have their photos shown in public, especially for educational purposes. Others are not. All the photos of people living with HIV-AIDS in this newsletter had to be approved by those photographed before I could use them. Likewise with revealing people’s names.

Because MSM (men who have sex with men), especially the transgender folks, are the people with highest transmission rates of HIV-AIDS as well as those who most often fall between the cracks, Health and Share Foundation makes a special point of reaching out to them. I was impressed to see transgender persons present at the HSF get-togethers of health promoters and outreach workers—often in leadership roles. Coming, as I do, from a nation (the USA) where LGBT relationships have only recently been decriminalized and where homophobia is still widespread, I found this inclusiveness uplifting.

Thailand has a long history of acceptance of erotic openness and diversity. Nevertheless, Western influence, with its pernicious taboos and hysterical sex-phobias, has been aggressively transmitted globally. Even Thailand—which prides itself on having never been colonized—has in recent years absorbed some pervasive Western customs and values.

In addition to the spread of Western customs and taboos into Thai culture, the fact that MSMs have the highest prevalence of AIDS in Asia has further accelerated the contagion of homophobia and transphobia. The resulting ostracism makes it harder for such marked people to get an education and a job. This pushes even more MSMs into commercial sex—and increases the spread of HIV-AIDS.

Home visits

During my stay in Thailand, Health and Share Foundation took me to visit a number of homes of persons who are especially vulnerable, often for a combination of afflictions. Here I’ll give a number of examples:

Mai—a Disabled Orphan Girl Who is HIV-Positive

Together with a group of volunteer community health workers, home care visitors, and outreach staff from the local district hospital, the HSF staff took me to a village on the outskirts of Khemarat, where we visited the home of Mai. Mai is an adolescent girl who contracted HIV-AIDS from her mother at birth. Both her parents died from complication of AIDS when Mai was quite young, and she was raised by her grandparents, who themselves are elderly and ailing. Mai’s older brother had to drop out of school to support the family. Mai has been treated with ARV meds since infancy, and regularly tested. She has no sign of AIDS-related infections. She is bright and basically healthy.

Unfortunately, when she was a toddler, Mai fell from a cart and struck her head, causing brain injury. This left her hemiplegic, with spastic paralysis in her right arm and leg. Eventually she learned to limp about with a crutch, but with great difficulty. Adding to her disability, her right foot, which flopped over to the side, developed a fixed deformity. This makes walking that much harder and more painful. A year ago the staff from HSF, who have visited Mai for years, made arrangements for her to have corrective surgery of her foot. But the girl was nervous about it—and her grandmother refused to allow it.

During our visit, Mai’s grandmother remained adamantly opposed to the corrective surgery for Mai. And Mai herself was unsure. To help them reconsider, I told them about my own history as a disabled child, with foot deformities similar to Mai’s. I took off my boots and braces, showed them my scrawny, emaciated feet, and explained how I, too, had been reluctant to have surgery. But after I finally did get the surgery I was able to walk much better.

Mai and her grandma listened to my story intently, and wonder of wonders, by the end of our visit, they both agreed. Mai’s grandma asked the HSF staff to arrange the surgery. Thanks to the Thailand’s Universal Coverage Scheme, it should be virtually free. I look forward to learning the results.

Mai’s life lies ahead of her, with big challenges. In her favor, is her intelligence and pluck. She is eager to learn useful skills, earn a living, and do something with her life. But she still has a lot of catching up to do. In her childhood she had no schooling after her accident. The village school is far from her home, and there was no public transportation. Nor was the terrain suitable for a wheelchair—which in any case she didn’t have. And her grandparents, with other worries of their own, didn’t push.

Now at 19, Mai is too old to attend the village school. However other opportunities exist, at least theoretically. In the neighboring city of Ubon-Rachathani there is a government-run Skills-Training Center for Disabled Youth. It has live-in facilities and is completely free. When Mai learned about it she was eager to attend, and HSF took her there to enroll. But when the director of the Center learned Mai was HIV-positive, she flatly refused to admit her. They insisted it would put the other students at risk.

Such a claim was blatantly false. Mai is not contagious. She has no symptoms of AIDS-related disease, and her viral load is consistently negligible. She is no danger to anyone. By law in Thailand all schools, training programs, and public facilities are required to give PLWHA (people living with HIV-AIDS) the same opportunities and rights as everyone else. But the director of the training center was adamant in her rejection of Mai.

A week after our visit to Mai’s home, when in the city of Ubon-Rachathani, we visited the Skills Training Center for Disabled Youth mentioned above, and met with the director and teachers. When we asked whether the Center admitted disabled youth who were HIV-positive and under supervised treatment, one of the teachers assured us that yes, the Center was required to accept PLWHA by law. But when the HSF staff pointed out that Mai had been refused admission at the Center, the director backtracked and made all kinds of excuses. There was no way they were going to admit Mai—the laws be damned. The problem is that there are no teeth in the laws. If the Center turns someone like Mai down, there is no legal recourse.

I suggested that as a minimum, schools and training centers should be required to prominently display a poster declaring the Rights to Admission and Equal Treatment of People living with HIV-AIDS. HSF will be working to establish this requirement. And I spoke about this days later in the talk I gave at the International Conference on Sustainable Development Goals, on May 25.

Mai’s Grandfather: Self-Administered Dialysis for Renal Failure

Mai’s grandfather did not join the rest of his family during our home visit, but stayed in a small back room that has been specially cleaned and equipped for his dialysis. He has kidney failure, which is a frequent complication of heart disease and diabetes.

In Thailand—as in Mexico and so many other low and middle income countries—in recent decades the pattern of the most serious illnesses has been changing. Today the biggest causes of death are from chronic non-infectious diseases, including cancer, high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke, diabetes, renal failure, and gout. These ills result, in large part, from changes in eating habits: namely over-consumption of less-healthy “modern” foods, sugared drinks, and tobacco. This upsurge in chronic degenerative pathology is one of the many downsides of Western-imposed “development” in the globalized free-market economy.

To deal with this pandemic of chronic non-infectious disease, especially in the mushrooming elderly population, the Thai Health Ministry is taking a number of innovative, cost-saving steps, including outreach from hospitals into communities and homes. This outreach is facilitated by a network of medical personnel, including a great many paramedics and volunteers.

To cover the escalating need for dialysis—which is prohibitively expensive when hospital-based—most people with renal insufficiency now get peritoneal dialysis (stomach cavity) at home, where a family member is taught to administer it. This not only reduces cost of medical personnel, but saves the family the expense of frequent transport to and from the clinic. Although peritoneal dialysis is less efficient than hemodialysis (direct to blood-stream) and requires more frequent applications, it is much less expensive. On Thailand’s limited budget, it has allowed more complete coverage for the multitude in need.

Arm—A Boy Who Lost his Leg from Cancer

On one of our home visits we saw an 11-year-old boy named Arm, whose leg had been amputated due to cancer. Arm lives with his mother and siblings in a thatched house with no running water. Arm’s family is very poor. His father is dead. And his stepfather, whom the family rarely sees, spends long periods of time in Bangkok, working as a day-laborer. From time to time he sends or brings a small amount of money back to the family. Millions of families are broken up like this, due to shortage of jobs and low wages in the countryside.

When Arm was diagnosed with cancer two years ago, he was told his only chance of survival was amputation—above the knee. At first both he and his mother were unwilling, but when his condition got worse, the Health and Share Foundation staff was able to talk them into the surgery, promising the boy an artificial limb. After a successful amputation, HSF arranged to have a modern, high-cost prosthetic limb made for Arm—free of cost—at a facility in a distant city.

A year later, when we arrived at Arm’s home, he was dutifully wearing his limb. He showed us how he could walk with it without crutches—fairly well. But his mother complained that he almost never used the limb, despite her scolding. The boy finally admitted he preferred walking without it, using a single crutch. We asked him to demonstrate. And without the limb, he was clearly far more agile and comfortable.

Soon we discovered why. The artificial limb was extraordinarily heavy! I pointed out that, although it was child-sized (and already too short for his other leg which was growing), it had been built using a heavy adult knee-joint and other hardware. And the resin socket was as thick and heavy as that needed by an adult.

Now everyone understood the boy’s concern. An option might be to have a lighter limb built for him—but it would only be temporary. During his growth spurt (which Arm was entering) constant adjustments and replacements would be required. Considering the circumstances, it made sense to listen to the boy and his suggestion. … With good reason the slogan of the Independent Living Movement is: Nothing about us without us!

The ‘BUDDY HOME CARE’ Initiative—A Win-Win Innovation

The Buddy Home Care initiative, launched experimentally by Health and Share Foundation in 2016, is one of the most exciting and innovative community health activities I have witnessed in years. Yet when you think about it, it is an obvious way to benefit two very vulnerable groups: 1) children in very difficult circumstances, and 2) elderly people with chronic illness who are often left alone.

For such elderly people with special needs, the Health Ministry has a program of Community Health Volunteers and Home Care Providers, who visit ailing old folks on a regular basis to help with their basic needs. But in practice the plan doesn’t always work as intended. Ideally there is one local Health Volunteer for every ten households, and one Care Provider for every six or so Volunteers. But even where these numbers are met, the providers don’t have much time to spend with each person in need. So many elderly people live alone, with no one to keep them company or care for them for long periods.

Likewise there are loads of children in Thailand in highly vulnerable situations. These include AIDS orphans, children whose parents have HIV-AIDS or chronic illness, children of broken homes or whose mothers are sex-workers, children with a disability, children whose family members use or sell drugs, kids at risk of getting involved with drugs themselves, and children of migrant workers. Often these kids have multiple disadvantages, little nurturing or care, and are quite lonely.

For both the elderly and the children, these problems are compounded by the fact that their families are often separated because the father (or sometimes the mother and older children) leave home for extended periods of time to find jobs in Bangkok, to try to earn a living and send money home. But sadly, when far from home, they often end up having sex with other women or men, and contract HIV-AIDS or other STIs, which they then carry home to their villages.

For all these reasons, elderly people with chronic illnesses often spend long periods of time at home alone, hoping for someone to come and assist them, or at least provide a bit of company.

The first step in implementing the Buddy Home Care program is for concerned community members to help their neighborhood health volunteer or home care provider identify especially vulnerable children, between 10 and 16 years old. Then the volunteer or provider invites the child to become a companion, or “buddy,” by visiting, befriending, and assisting, a vulnerable elderly person on a regular basis.

This “buddy” approach has potential for bringing out the best in everyone, and of filling a gap in the troubled lives of both young and old. The kids can help out in many simple ways, such as running errands, adjusting cushions, or rubbing painful muscles. Some learn to take blood pressure and help keep records. But perhaps their most important role is just being there, being young, and being friendly. When it works well, it can be a real boost in the self-esteem of kids.

When I arrived on home visits to chronically ill old people, they often looked lifeless and dejected. But the moment they glimpsed their young “buddy,” their faces would light up. And when the child gave them a big hug, they would reach out and hug the child back with an energy and joy no one would have believed they had in them.

Preparatory Learning Sessions for the Buddy Home Care Visits

As a part of the Buddy Home Care procedure, staff of Health and Share Foundation periodically conduct interactive sessions with both health workers and children together. At the session I participated in, there were about 20 children and 20 health volunteers and home care agents.

Accompanying Some of the Buddy Home Care Visits

I had the opportunity to tag along on some of buddy home care visits. Here are examples:

Home of an Elderly Couple, Both Incapacitated by Strokes

The first elderly couple I visited were both disabled by stroke, and they lived alone in a house on stilts. Their grownup children had migrated to Bangkok to find jobs, and when possible send money home. Occasionally the frail couple is visited by local health workers, but most of the time they have to fend for themselves. The old women is severely paralyzed and has a hard time communicating. She can’t get out of bed and is totally dependent on her disabled husband.

Her husband, in turn, is partially paralyzed and uses a wheelchair. All things considered, he does amazingly well. His biggest difficulty is leaving the house to go shopping. Because their living quarters are up high, on poles, he lowers his wheelchair out the window and then scoots down the steep stairs on his butt. The path to the road is too rough to ride in the wheelchair, so, as best he can, he uses it as a walker. Sometimes neighbors help out.

A Visit to a Woman with Diabetes and Renal Insufficiency

The elderly lady in my next visit was diabetic and had renal insufficiency. She was confined (unnecessarily) to bed. When we arrived the old woman was very gloomy, but began to cheer up, especially with warm friendly touch of her buddy, a local neighborhood girl.

It was clear the old lady was frustrated by staying in bed doing nothing. She insisted she was too weak to stand up or try to do anything for herself. Undoubtedly she was weak. But it appeared her overall debility came in part from inactivity. Her large, supportive family was inclined to be overprotective. After coaxing her to sit up in bed, we asked her if she would like to try standing. She said she couldn’t—and at first was unwilling to try. But when her young “buddy,” whom she had grown very fond of, begged her to give it a try, the old woman consented.

By the time we left, the old lady and her family had a whole different view about what was possible. They discussed many things she could do assist with household activities. Her friend helped her figure out how to manage.

A Man Disabled by Stroke, with Chronic Skin Sores

Among the poorest families we visited was an elderly couple who lived alone and essentially had no income. The man, who’d had a stoke nine years before, was emaciated and had a serious skin condition with many open sores. The couple’s children had left to hunt for jobs in Bangkok but had a hard time making ends meet, and they were rarely able to send anything back to their parents. Government assistance was meager and proved hard to get.

The old man was completely dependent on his wife. With help he could manage to stand up. Holding onto something, he could move with a Parkinsonism-like shuffle, but his balance was precarious. Getting to the outhouse with his wife’s help was a slow, exhausting process for both, and often they didn’t arrive in time. A son—a carpenter—on one of his infrequent visits home, had put up an improvised railing along the outer wall of the house and across to the latrine, but the old man couldn’t get there without assistance and a danger of falling. We suggested that his son, on his next visit home, make a simple portable commode—just a box with a round hole in it, over a bucket—so that instead of going to the toilet, the toilet could come to him. They thought that was splendid idea.

Getting food was a major struggle since the couple usually had no money. The old woman said some mornings she tried to catch fish in the river, but it was slim pickings. Their main source of food was the Buddhist temple, where the priest would share with the old woman some of what devotees from the village brought as offerings—mostly rice. Other than that, the couple often went hungry.

The old man’s stubborn skin condition had been examined by health workers and doctors, who prescribed all kinds of antibiotics, ointments, and lotions—mostly to little avail. It occurred to us that the chronic rash and sores might be due to nutritional deficiency—among other possibilities the lack of vitamin D. The man almost never consumed milk products, and he lived completely indoors, which gave him little exposure to the sun. Sunlight, of course, helps the body produce its own vitamin D. Wouldn’t it be nice if the man’s obstinate skin condition could be cured by something as free and ubiquitous as sunlight!

As we talked about all this, the old man’s young “buddy,” a shy, rather fidgety 12-year-old boy, listened carefully. When he grasped the idea, he offered, every time he visited, to escort his elderly buddy out into the sunlight, help him take off his shirt, and sit with him in the sun. The boy understood that at first he should do this for just for a just few minutes, then a bit longer and longer as his skin adapted to sunlight.

Both the man and the boy are willing to give this a try. If it works, fine. And if it doesn’t, at least the camaraderie of sunbathing perhaps will nourish both their souls.

The ‘SMILE FACTOR’

Other homes that we visited as part of the Buddy Home Care initiative reaffirmed my impression of the huge potential and human value of this innovative approach. Time and again, it was the presence and concern of the child “buddy” that seemed to be the best medicine for the ailing, often quite lonely, older person. The children enjoyed their role as home care “buddies” and felt good about offering their help and friendship to someone who needed and appreciated it.

In visit after visit, the elderly chronically ill people we called on, at first looked sullen and disconnected. Many sullen frowns and blank stares. But after a warm hug from their young “buddy” they would burst into a happy, grateful smile.

Some evaluators of community programs say the best measure of success is the SMILE FACTOR. I agree.

Reflections: Argument for Legalizing Sex-Work and Drugs

In comparison with the United States, Thailand currently has far more tolerant policies with regard to illicit drug use and prostitution.

Drug use and commercial sex will exist, no matter how much they are penalized; their criminalization only leads to greater violence, exploitation, and corruption (as was seen in the United States during the prohibition of alcohol). Likewise, the so-called “War on Drugs,” which the US has escalated worldwide, has created a tsunami of violence, turf warfare, arms smuggling, extortion, corruption, and human-rights violations. In Mexico alone, where over 200,000 drug related murders have taken place since 2006, the nation is close to becoming a failed state. Meanwhile the United States has by far the world’s largest per-capita prison population. With 5% of the world’s people, the US has 25% of the world’s prisoners. Over half are incarcerated for drug-related crimes. Most are non-violent drug users and petty street dealers—many of whom peddle drugs because they are from racial minorities who have a hard time getting decent jobs, to feed their families.

Thailand, in contrast, focuses on treatment and prevention rather than on punishment. It offers habituated drug users free needle exchange, and free testing and treatment of HIV-AIDS, as well as education and rehabilitation. Likewise Thailand’s current practice of working with people who sell sex is to help them do it more safely rather than harshly punishing them and thus driving them underground. Such policies with regard to drugs and sex-work are not only kinder, but are more effective in reducing crime and promoting health.

Protecting National Boundaries

Another area where the contrast between Thailand and the United States is most striking is in their respective treatment of people who come into their nation from neighboring countries looking for work. This is especially so now under US President Donald Trump’s xenophobic, racist stand on migrants.

Not only does Thailand make entry across its borders relatively simple and friendly, but it offers free medical treatment—including of HIV-AIDS—even to non-legal migrants. In contrast, President Trump is determined to build a huge trillion-dollar wall to prevent the Mexican and Central American neighbors of the United States from coming in. And as for those who are already in the US without papers—heaven help them!

Thailand’s “good neighbor” policy is not only far more humane, but also more pragmatic. By providing basic social service to all immigrants, including free testing and treatment of HIV-AIDS, the disease can be much more effectively brought under control. A society will be much healthier when everyone—including outsiders and minorities—are treated equally and fairly—and where there is universal health coverage for all.

Conclusion: Two Worlds

Thailand has its feet in two worlds.

One is the world of love, caring, and sharing—which is the natural social habitat of an intelligent, interdependent species. This is the sphere of oneness we are born into—that comes to the baby with breast milk. It is the state of togetherness, of unity, of the fellowship of life. All Life. The world where everything is unconsciously and wondrously connected.

The other is the divided world we are trained into, and are seduced to espouse. The world of separateness. Of selfishness. Of mirrors. The world that pits us against one another for the illusion of personal gain. The world that measures our worth by what we have—or think we have—and not by what we are or how much of ourselves we give. A world that builds a facade of self-worth on the hunger of others.

The contradictions between these two worlds are more glaring in Thailand, perhaps, than elsewhere because it was never colonized. It was able to keep elements of its preindustrial mystique more intact than could the lands overrun and reshaped by colonial powers. Thailand also had the benefit of a strong grounding in Buddhism, which, beneath its trappings, is founded on the interconnectedness of all things. Thailand still harbors elements of the old ethos of compassion, an ethos grounded in the realization that your happiness and my happiness are inseparable.

I suspect that it is this venerable ethos of oneness and compassion that has helped Thailand realize its exceptional advances toward universal health coverage. It was this spirit that energized the work of the generous volunteers and highly committed employees of Department of Health that I met. I was inspired by the willingness of so many professionals to listen and to relate to people, even in the most humble situations, including impoverished immigrants and members of groups that are too often denigrated and ostracized. It is this spirit of inclusion, even of the underdog, that I believe lies behind the healthy side of Thailand.

But at the same time Thailand—or at least much of its ruling class—has bought-into the Western “development” model, which pursues imbalanced and unsustainable economic growth-at-all-costs. The country’s constant power struggles and military coups reflect this … as does the incessant corruption at the highest levels … as does the failure of countless officials to obey the nation’s humanitarian laws (such as those guaranteeing free health services to indigent immigrants). Perhaps one of the most telling signs of Thailand’s having entrapped itself in the toxic World of the West is the growing polarization between the haves and have-nots, which contradicts its outstanding pursuit of Health for All, along with any surviving aspirations for democracy.

Be it in Thailand or the US, the fragile flower of democracy has little chance of viability where inequalities of wealth and power are so great.

For all that, Thailand has indeed made admirable strides towards health coverage for all. These strides—regardless of the ruling class’s intentions—are awakening and empowering the populace to strive for greater equality, inclusion, and sustainability across the board. Such are the seeds of change.

Herein, perhaps, lies hope for a healthier nation, and for a healthier, more durable world.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |