Drugs and Disabilities

In Mexico today, widespread use of addictive drugs has become a major social and health problem, especially among youth. In this newsletter we discuss how extensive trafficking and consumption of drugs have created new challenges for the community health and disability programs we are involved with, and we describe a groundbreaking initiative run by and for disabled persons who got hooked on drugs and are now trying to stay off them by devoting their lives to assist others in need.

Mexico’s Drug Crisis

Back in the mid-1960s, when I began community health work in the Sierra Madre, cannabis, and opium poppy were already grown by some villagers, largely as cash crops to supply the demand by pot and heroin users in the United States. But local consumption was minimal. Not until Mexico became a major pipeline for cocaine from South America to the US did drug use in Mexico begin to escalate drastically. Traffickers from South America intentionally hooked youth of the Sierra Madre on cocaine, so they would swap their home-grown goma (raw opium gum) for coca (cocaine). By so doing, the traffickers could greatly multiply their earnings. The amount of raw opium they paid the equivalent of US$300 for in the Sierra Madre would sell as adulterated heroin in Los Angeles for as much as a million dollars!

Once cocaine use began to spread in Mexico, it led to growing use of other substances—everything from glue-sniffing by street kids to opioid painkillers and “Roche-2” by urban youth. The last decade has seen an explosion in use of crystal methamphetamine—known as cristal—which is not only highly addictive but pernicious to both body and mind.

Aggravating the drug scene in Mexico is the aggressive WAR ON DRUGS spearheaded by the US government, which has fueled both the powerful drug cartels in Mexico and the pervasive corruption at every level of government of both countries (but more conspicuously so in Mexico). In recent decades the Mexican cartels have become so powerful and well-armed that they often hold the upper hand over the police and sometimes even the military. The cartels’ massive armaments—including machine guns, AK47s, hand-grenades, and other military assault weapons—flood across the border from the United States. In the US they are easily purchased because of the lack of effective regulations, thanks to the overpowering “right to arms” lobby of the American Rifle Association.

All in all—considering 1) the massive US demand for illicit drugs, 2) the easy procurement of weapons from the US, and 3) the counterproductive War on Drugs—the United States is in large part responsible for the escalating drug crisis in Mexico. The manifold damage is far-reaching. Linked to the spiral of trafficking and addiction, in the last decade there have been over 100,000 drug-war-related homicides—and at least 27,000 disappearances—most with impunity and frequently with suspected police or government complicity. With the staggering levels of unresolved crime, corruption, and human-rights violations, Mexico is close to becoming a failed state. On top of all that, the gulf between the wealthy and the destitute continues to widen—as it does in the US and in most of the world. Meanwhile, Obama and Trump’s massive deportation back to Mexico of millions of undocumented workers, not only increases joblessness and hardship south of the border, it drives millions of the desperate unemployed into crime and drugs.

Impact of the Drug-Scene on the Community-Based Programs

In previous newsletters we have written about how the increase in the growing, trafficking, and use of illicit drugs has changed village life in the Sierra Madre—and how, in turn, this has affected the villager-run health and disability programs. Mountain communities that traditionally had a strong sense of unity and mutual self-help have become increasingly divided, stratified, and distrustful. More and more youth got hooked on drugs, and many began to steal to sustain their habit. Drug gangs proliferated and in time turned to bribery, extortion, kidnapping, death-threats, torture, and murder to establish their turf and power. Meanwhile PROJIMO (the village Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico)—which had originally been an easygoing, friendly collective set up to help meet the needs of disabled children—increasingly became filled with troubled young drug-runners and -users who had become disabled from bullet wounds.

With all the drug growing and trafficking eventually the situation in the whole Sierra Madre became intolerably oppressive.

As PROJIMO became widely known as one of the few places in Mexico where spinal-cord injured people could survive and be functionally rehabilitated, paraplegic and quadriplegic persons from all over the country found their way to the small village center. Of these, 80% had been disabled from bullet wounds—mostly drug-related. Because so many came out of a subculture of drugs and violence, the program had to add psychosocial rehabilitation to its services. But even so, incidents of drugging and violence occurred within the program, and its former tranquil, trustful atmosphere was compromised. Understandably, fewer families brought their children to the program.

With all the drug growing and trafficking—coupled with robbery, kidnapping, extortion, and killing—eventually the situation in the whole Sierra Madre became intolerably oppressive. Little by little the local villagers—many of whom had lived in the mountains for generations—moved out to coastal towns and cities which, in those days, were somewhat safer. Now they no longer are. The PROJIMO team valiantly hung on in the village of Ajoya as long as it could. But eventually it split into two separate programs, one of which moved out to the coastal area three years before the other. The first—which covers a wide range of community-based rehabilitation needs—moved to the small town of Coyotitán near the old international highway. The second—which focuses on making individually-adapted wheelchairs for children—moved to the small village of Duranguito, even nearer the coast. The two programs currently function independently.

Use of Addictive Drugs by Program Workers

Despite efforts by the PROJIMO programs to move far from the area with the most pernicious drug scene, it was not long before the coastal villages they’d moved to became overwhelmed by competing drug gangs—and by the proliferation of addictive drug use. By then crystal methamphetamine, concocted in makeshift clandestine laboratories, was the most popular hard drug. Sold by “vigilantes” of the local drug gangs, it was available at a modest price on almost every street corner.

The village of Duranguito, where the PROJIMO wheelchair-making team had been formally invited to rebuild their workshop, was, at the time the program moved there, a tranquil little pueblo. There was a fair bit of alcohol consumption but little use of hard drugs. Two years after the wheelchair program moved in, however, the village became the outpost of a branch of the Sinaloa Cartel—and drug use escalated. More and more local youth began to experiment with hard drugs—mostly *cristal—*and sometimes they came by the wheelchair shop to get their motorcycles welded, or just to hang out. In time, friendships and camaraderie developed. It was no great surprise that a few of the disabled team-members in the PROJIMO workshop began to experiment with popular drugs … and little by little get hooked.

As it happened, some of the disabled team-members who got into drugs were among the most caring and innovative workers. They’d shown concern that the wheelchairs they built optimally met each child’s needs. But sadly, under the influence of cristal—on which they became increasingly dependent—the quality of work deteriorated drastically. Also they grew moody and defensive. They began to steal to satisfy their cravings—and to make and carry weapons. Meetings were held and remedial efforts made … but in vain. Eventually those who were most deeply hooked were asked to leave the program. For some, this proved disastrous. And their departure was a great loss to the program and to the children they could be helping.

We (PROJIMO, HealthWrights, and friends) have helped some of these addicted team-members to participate in AA-type drug rehab programs. Mostly run by former addicts, such programs abound in urban Mexico. While interned in the centers, the addicted people become drug-free and committed to stay clean. But too often their good intentions are short-lived. Even after months of rehab, after they get out they tend to relapse. After all, they return to the same drug-saturated environment.

The larger community sees them as losers. Branded as disabled as well as druggies, they have a double cross to bear. They are treated with a mixture of pity and contempt, and are subject to discrimination. They have great difficulty finding a job. Depressed and deflated, they seek out the company of others who are down-and-out, and despite their best intentions, slip back into drug use.

The Need For Spirit-enriching Programs for Disabled Persons Fighting Addiction

In today’s world there are loads of programs for disabled persons, and loads of programs for recovering addicts. But there are virtually no programs for those who are both disabled and addicted. The need of such programs—ideally run by disabled recovering addicts themselves—presents a challenge. Some of our disabled comrades who have tried to give up drugs believe they might stand a better chance of staying clean if they could collectively do something tangible to help others in need, and by doing so, gain both self-esteem and public respect. If they could earn a living in the process, so much the better. In order to bring this dream to fruition, a proposal was formulated to start a service program run by and for disabled ex-drug-users, to help special-needs children by advocating for their rights, and providing them with needed services.

So it was that a modest new program, dubbed by its members “Habilítate Mazatlán” (Enable-Yourself Mazatlán) was conceived. The group appended “Mazatlán” to the name because most of them live in or near the beautiful but troubled coastal city of Mazatlán.

Habilítate Mazatlán decided to focus on four service activities:

1) Facilitate fun, participatory, discovery-based Child-to-Child activities with schoolchildren, to encourage them to be kinder and more inclusive with children who are disabled or different.

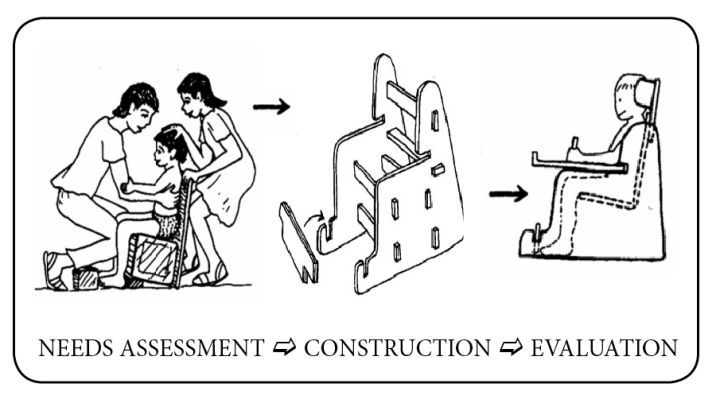

2) Build custom-designed special seating out of recycled cardboard, for disabled children who can benefit from this.

3) Run a modest wheelchair repair shop to service and provide wheelchairs to those in need.

4) Cooperate with PROJIMO Duranguito by identifying children who need custom-made wheelchairs or other assistive equipment, and to help track down the resources to cover the costs.

Habilítate made arrangements for these children, from a special education program in Mazatlán, to have personalized wheelchairs made for them by PROJIMO Duranguito.

A primary objective of the program is to provide quality services and equipment at the lowest possible cost—or free to those in greatest need. The program looks for donations and organizes money-making events—such as dinner parties—at which they present slide-shows of their work. Money that is collected is used to pay for building materials, and, to the extent possible, to provide modest earnings for those who work in the program.

Picture Presentation: Child-to-Child Workshop Facilitated by Habilítate Mazatlán

To date the Habilítate team has been most active in Child-to-Child workshops and special seating made with cardboard.

Child-to-Child activities are participatory, discovery-based, and fun. They involve simulation games, story-telling, and eye-opening, curiosity-rousing, problem-solving ventures. At its best, Child-to-Child is based on the principles of “pedagogy of liberation” in which the challenge is to draw ideas out of the learners rather than push them in. Innovative activities are facilitated, in which the children make their own observations, draw their own conclusions, think about things they might do to improve unfair situations, and make suggestions regarding collective action for the common good. Although a lot of thoughtful planning may go into such activities, the process often turns out delightfully spontaneous and inspirational … if somewhat unpredictable.

Child-to-Child was initially developed to help children learn what they can do to protect and improve health, especially of infants and toddlers. However the PROJIMO programs in Mexico have adapted diverse activities for disability awareness-raising and inclusion. One of the leaders of this approach in Mexico is Rigoberto (Rigo) Delgado, a spinal-cord injured (quadriplegic) young man who spent years at PROJIMO Coyotitán—first for his own rehabilitation, later as a program leader.

(See Newsletter #68 on Rigoberto Delgado.)

Because Rigo now has vast experience leading Child-to-Child workshops with a disability focus, the Habilítate team invited him to help facilitate their first workshop, with schoolchildren in Mazatlán—and in the process teach the team the methodology (through learning-by-doing). Rigo gladly agreed—and did a great job.

The first Child-to-Child workshops Habilítate held were in the colorful facility of Grupo Los Pargos. Los Pargos is a cooperative which was formed 20 years ago by families of disabled children. Now all the children have grown up, but they still gather at the center on weekday afternoons. In the mornings they loan a big room at the Pargos center to the Ministry of Education, which uses it as a primary school classroom.

After these games everyone discusses what it is like not to see well. They also realize that a child with a disability has the same feelings, needs, and right to play as do other children.

In a final discussion session the children commented on how they enjoyed the Child-to-Child activities and what they learned. Their feedback for the most part was quite positive. Some said what they enjoyed most was being to talk openly with members of the Habilítate team about their disabilities, and get direct, caring answers. The kids felt that in the future they would feel more comfortable about making friends with someone with a disability because, as one little girl put it, “On the inside, we’re pretty much the same.”

Special Seating Made of Cardboard: A Project in Which the Habilítate Team Designs and Constructs Individualized Seating for Children with Especially Challenging Needs.

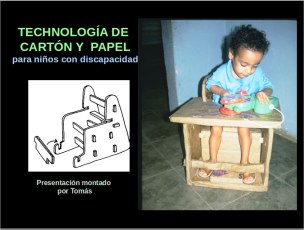

The Idea of Appropriate Paper-based Technology (APT)

Many disabled children, especially when young, can benefit from special seating adapted to their individual needs. This is particularly true for children with cerebral palsy, which today is one of the commonest disabilities in children. Because of spasticity, weak muscle tone, uncontrolled movements, or a combination of these, such children often have difficulty assuming and sustaining the stable position they need in order to do more things and learn new skills—such as control their head, use their hands, self-feed, etc. Sitting in a good position often may help reduce or “break” the spastic pattern, allowing the child to relax, sit more comfortably, and do more things.

But the needs and possibilities of every child with cerebral palsy are different. Sometimes a seat carefully designed for an individual child can make a notable difference, not just for sitting in a healthy position, but in the child’s overall comfort, body control, and functional development.

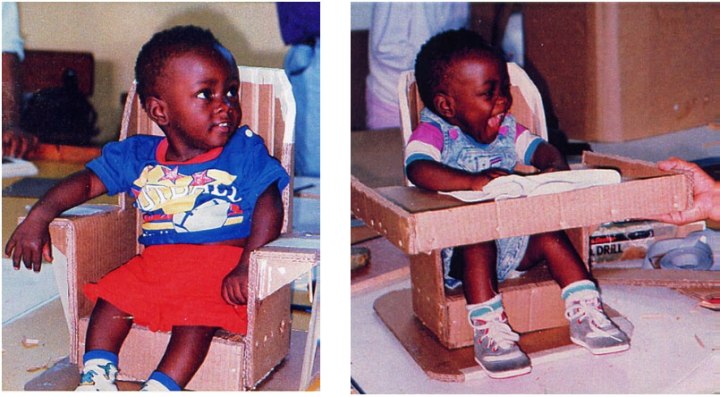

Effective seating for such children is an art as well as a science. Unfortunately many children never get the individually designed seating that could benefit them most. Professional special seating tends to be expensive. Children from low-income families are often left behind. For these reasons, the Habilítate team decided that its main service project should be the production of custom-designed special seating for children who need it, at low cost. As their main building material, they use recycled cardboard. This low-cost method, called “Appropriate Paper-based Technology” (APT), was first developed in Zimbabwe, Africa, by Bevill Packer for furniture, toys, and household items, as well as for seating and assistive devices for disabled children.

Not only are old cardboard cartons free or low-cost, but cardboard is much more malleable, adaptable, and easy-to-work-with than is wood or metal. APT is now being used in many countries—including England, where families learn to make adapted seating and other equipment for their disabled children.

The first step toward making cardboard seats is to glue several layers of corrugated cardboard from cardboard cartons together and press them under weights to form flat plywood-like sheets one to one-and-one-half cm thick. Cheap glue can be made by mixing flour and water. Or white wood-glue, thinned down with water, works well, but is more costly. The finished seat can be painted with water-resistant lacquer to prevent soiling.

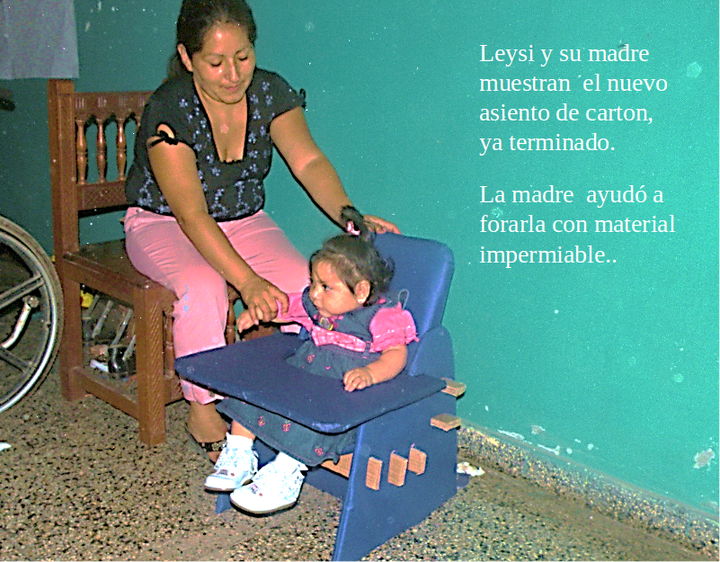

Picture Presentation: A Special Cardboard Seat For Susi—Designed and made by the Habilítate Team

Susi is a six-year-old girl with cerebral palsy. She has “extension spasticity”: her whole body tends to straighten stiffly, and more so when she is nervous or excited.

Examples of Other Special Seating Made in Habilítate

Generous Souls

One of the challenges of the special seating project has been how to cover costs. Although the cardboard is cheap or free, the process of evaluating the child’s needs, designing and constructing the seat, and making the necessary modifications entails a fair bit of meticulous work. Most members of Habilítate are otherwise unemployed and have a hard time making ends meet. For their meticulous work on these special seats they need—and deserve—some form of income. However most of the children’s families are too poor to pay more than a small token.

Fortunately a humanitarian doctor, Dr. Carlos Miyazaki—who has collaborated with Habilítate from the first—has contacted some of his well-to-do, good-hearted friends. Some of these are now stepping in as “sponsors” of individual children. They cover the cost for the seat, including a modest wage for those making them.

In addition to financial help from individual donors, the municipal “Integral Family Development” program (DIF), which runs a rehabilitation service for disabled children, has become an energetic advocate for Habilítate’s special seating project. DIF now helps supply large sheets of cardboard and other supplies—as well as refers children who need special seating. DIF has also made a physiotherapist (PT) available to help with the evaluation of the children’s needs and to make suggestions for seating design. The young, highly motivated PT who is filling this role is both contributing and learning a lot.

The president of DIF, who always is the wife of the municipal president, has become so enthusiastic about Habilítate Mazatlan and the quality of its specialized cardboard seats that she makes frequent visits to the work-site. And each time a new seat is delivered to the child, she arrives with a covey of key people and a photographer. Shortly afterwards articles come out, both in the DIF public newssheet and in the local newspaper.

In this way the rehab programs of Mazatlán are learning about these new ways of assisting disabled children. Of equal importance, perhaps, the larger community is learning about the remarkable social contribution that can be made by disabled persons who have battled drug addiction.

Hopefully this service project will have an impact, not only on how the larger community looks at disabled people and at recovering drug users—and at those who are both—but also on how our group of disabled recovering users view themselves. These latter will acquire, we must hope, a new self-respect … which comes with their doing something worthwhile and admirable, and with the joy of helping enhance the possibilities of children with exceptional challenges.

Much of the accomplishment of Habilítate, and its rewarding liason with DIF, is thanks to Dolores Mesina, a disabled social worker whom we at PROJIMO have known since adolescence, when we helped her get spinal-cord surgery. Dolores was one of the first wheelchair-riders to get a university degree in Mazatlán. As a long-time social worker with DIF, Dolores has helped open many doorways for collaboration with that institution. She is a dynamic member of the Habilítate team. Though she has never used drugs herself, she has a lot of experience with habitual users and is sympathetic to their struggles. Dolores has played a central role in Habilítate’s logistics and public relations, for which we warmly thank her.

An Unmet Need: A Drug-rehab Center that Welcomes Disabled Persons

Habilítate Mazatlán is not always successful in its intent to help its members stay off drugs. Crystal-meth addiction is notoriously hard to shake. Some of the group’s most caring and capable workers have slipped again into heavy drug use and have needed to go back into drug-rehab centers. Unfortunately, in Mazatlán—and to the best of our knowledge, in Mexico as a whole—there are no drug treatment facilities equipped for use by people with disabilities that require special accommodations.

The policy of the rehabilitation center is not to admit disabled persons who need special accommodations.

One of our wheelchair-riding Habilítate members who recently relapsed—whom here I will call José—is now voluntarily interned at the Drogadictos Anónimos center in Mazatlán. However he was accepted at this DA center only because his uncle (a former drug user) is now the secretary there. But the policy of this center—like virtually all others—is not to admit disabled persons who need special accommodations. Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán has no ramps, so José must be manually carried up and down steps. Likewise, the bathrooms are not wheelchair-accessible. Housing laws are another concern. Because the center fails to meet regulations for disabled residency, every time an inspector shows up, José (or at least his wheelchair) has to sneak away into hiding.

Given the vast unmet need for drug centers that are willing and able to serve disabled people, members of Habilítate recently met with board members of Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán to explore the possibilities to adapt the center for legal accommodation and friendly inclusion of disabled persons. To meet state requirements, this will mainly entail building a few small ramps and making at least one bathroom wheelchair accessible. In all, it shouldn’t cost more than US$2,000.

HealthWrights has agreed to try to raise the money to put into operation what we believe will be the first drug-rehab center in Mexico that is specifically equipped and committed to welcome recovering addicts who are also disabled.

The Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán center is one in a chain of 37 such centers throughout Mexico. If the Mazatlán branch can transform itself into a disability-friendly facility, it could become a catalyst for far-reaching change. With encouragement others may follow suit. The time is propitious, since “disability rights” are currently a prevailing concern internationally.

In the US, donations made through HealthWrights are tax deductible. Click here for more info.

End Matter

Do You Want To Study Spanish Online?

Rigo Delgado, who helped facilitate the Child-to-Child program described in this newsletter (and also the subject of Newsletter #68) is again offering basic and conversational Spanish classes by Skype, To see the announcement, click here.

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |