PROJIMO Leader Mary Picos Has Passed Away

Very sadly, just a few weeks ago (Feb. 22, 2018) Mary Picos—the dynamic paraplegic leader of the PROJIMO community-based rehab program for 35 years—died from fulminating septicemia caused by an infected pressure sore.

David left the following announcement on the HealthWrights Facebook page:

Mary Picos—Co-Director of PROJIMO—Has Passed Away

With deep sorrow the staff and workers at PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) inform friends and supporters that Mary Elena Picos Solian, co-director of PROJIMO Coyotitan, died unexpectedly on February 22, 2018, in a hospital in Mazatlan. Her death was evidently caused by a fulminating case of septicemia, resulting from infected pressure sores—complicated by diabetes—which she had been battling for months.

Mary had been a dedicated leader and administrator of PROJIMO for 35 years. She first was taken by her family to PROJIMO in 1982, after she became paraplegic in a car accident on her honeymoon. Her young husband (the driver), who was uninjured, abandoned her, and Mary was depressed and suicidal. But in PROJIMO she discovered new meaning and joy in life by helping disabled children—and threw herself into the process heart and soul. She was a star apprentice of David Werner in the evaluation and rehabilitation of disabled persons. Soon she became a skilled rehab provider and—together with Conchita Lara (also paraplegic)—joint coordinator of the program. She married another disabled person, Armando Nevarez, who likewise had come to PROJIMO for his own rehabilitation and then became a brace and limb maker. Together they had a daughter Lluvia, who soon became a junior rehab assistant herself.

Over the years, through good times and hard times, Mari worked tirelessly to keep the program functioning and solvent. Funding was a constant challenge, and without Mary’s ceaseless efforts and ability, there were times when the program might have gone under.

Mary became such a strong central figure in the program that with her sudden death, in her fifties, the program is faced with major challenges. But the team of disabled workers—with Conchita Lara as the remaining coordinator, is determined to reinvigorate its services to the most needy of disabled persons.

If you would like to see some of their most recent activities since Mary left them, see their Facebook page: PROJIMO A.C.

This note can be found here.

Cardboard Cushions Help Heal Stubborn Pressure-Sores

A Cardboard Cushion Works Better than a Roho to Combat Mónica’s Pressure Sore

Mónica is a teenage girl with spina-bifida. Paralyzed from her waist down, she uses a wheelchair. When the Habilítate team first met her she had a large chronic pressure sore over her right ischium (the part of the hip bone one sits on). Despite using an expensive Roho cushion (an inflatable rubber cushion, composed of many little air bags, widely prescribed to combat pressure sores) she’d developed a chronic sore that had gradually worsened for two years. Because it was near her anus and she lacked normal bowel control, the open sore constantly got contaminated and infected. It grew so deep that the bone became exposed. Finally doctors performed a colostomy (surgery to empty bowel-content into a plastic bag through a hole in her belly) to keep the sore from getting contaminated. But the sore persisted. Mónica dropped out of school and spent most of her time lying on her side, in hopes the ulcer would heal. But every time she sat in her wheelchair, the sore got worse. So mostly she stayed in bed. Increasingly depressed, she lost a lot of weight and strength.

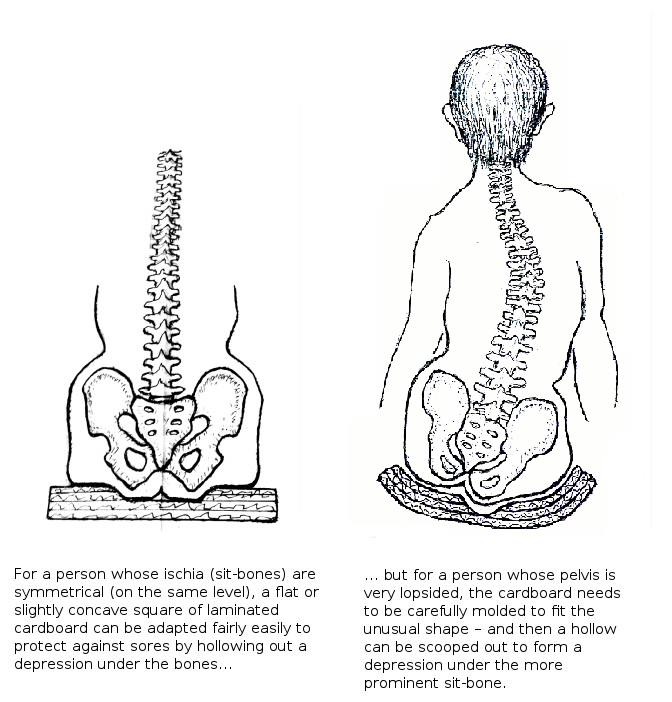

The Roho cushion, soft and even-pressured as it is, simply did not provide adequate protection. Part of the problem was that Mónica has an extreme S-shaped spinal curve (scoliosis). When she sits, her pelvis is so lopsided that her full body-weight rests on her right ischium (sit-bone), which is much lower than her left. This pressure there persists even with the very soft, pliable Roho cushion. So with her spinal curve, even a Roho didn’t prevent a pressure sore — or allow it to heal.

What Mónica needs is a cushion that is custom-molded to accommodate the lopsided shape of her backside, with a pit hollowed out under the protruding ischium so that pressure over the sore is completely relieved. But creating such a cushion is easier said than done! It calls for ingenuity, not money.

With her spinal curve, Mónica’s pelvis is so lopsided that when sitting, the full weight of her body is over her right ischium (sit-bone)—and even a Roho cushion didn’t prevent a pressure sore from forming there.

In the past, Project PROJIMO (the Community Based Rehabilitation program now in the village of Coyotitán) used to make personalized cardboard cushions. The team got the idea from Ralf Hotchkiss, a paraplegic rehab-engineer who for decades has helped spinal-cord injured persons in dozens of countries set up small workshops to build low-cost all-terrain wheelchairs. Ralf—who has battled with his own stubborn pressure sores—conducted a series of evidence-based pressure-measuring tests with handmade cardboard cushions. He found that a precisely fitted cardboard cushion can reduce pressure over bony areas of the buttocks better than costly air-cushions like Roho or gel-cushions like Jay.

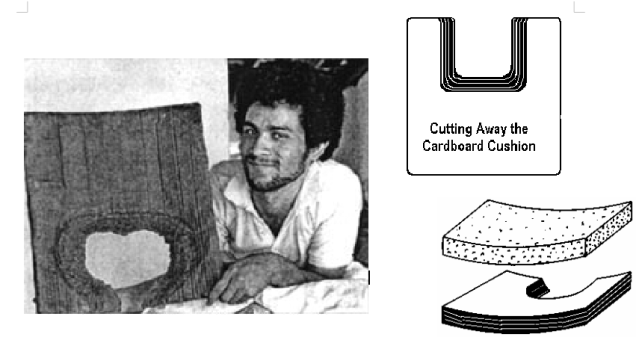

Jacinto, the paraplegic young man in the photo (above), made his own cardboard cushion at PROJÍMO. He cut a section out of it, as shown, to reduce pressure against his ischia (sit-bones). On top of the cardboard he put a sponge-rubber pad. Using this homemade cushion he didn’t get any more pressure sores.

Creating a cushion for Mónica was an unusually daunting challenge.

Unfortunately, at PROJIMO, these handmade cardboard cushions never became widely accepted. Most potential users (including some of the PROJIMO staff) simply didn’t believe that assistive devices made of such cheap, common material as cardboard could be any good. Disdainful preconceptions are hard to overcome.

But Mónica and her mother, though doubtful, were willing to give it a try. Initially the Habilítate team was also skeptical and insisted I work on it with them.

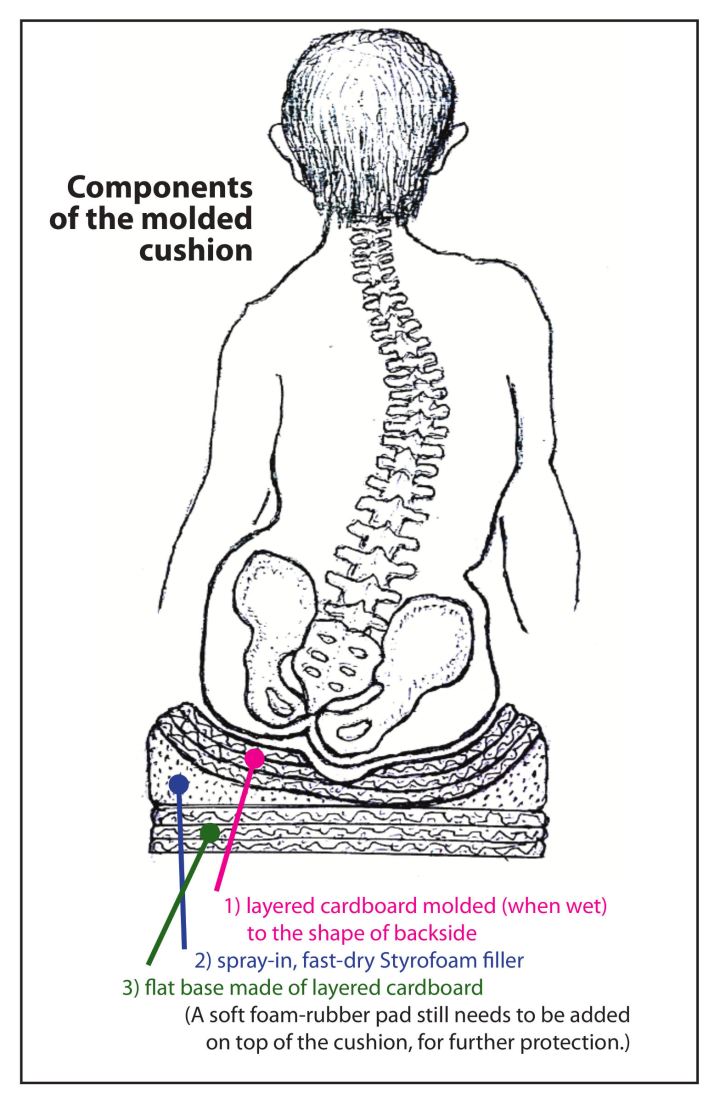

Creating a cushion for Mónica was an unusually daunting challenge. For someone whose spine is fairly straight and whose buttocks are symmetrical (on the same level), a protective cushion can be made simply by gluing squares of corrugated cardboard together and carving out a heart-shaped or v-shaped depression to minimize pressure under the sitbones and the coccyx (tail-bone). The cardboard is then moistened and the person sits on it for a while to more-or-less mold it to the contours of their behind. It is then left to dry. To complete it, two layers of spongy foam-plastic—a firmer one below and a softer one above—can be fixed atop the cushion.

However, molding a cushion to fit Mónica’s unusually lopsided backside called for a more individualized method.

To form a cardboard mold that fits the shape of Mónica’s asymmetrical pelvis, first we put a very thick layer of sponge-padding (about 15 centimeters deep) in the sagging cloth seat of her wheelchair. On top of the sponge (covered by a plastic bag) we placed a thin (one centimeter thick) square of moist, laminated cardboard, the layers of which had just been pasted together, so the carpenter’s glue was still wet. We had Mónica sit on this damp throne, in a well-postured, comfortable position, for about 20 minutes. (More time might have been better, but we worried about the prolonged pressure on her sore.)

Then her mother carefully lifted Mónica straight up out of the wheelchair. The cardboard mold was left to dry, without moving it, until it was quite firm. Then more squares of damp, pliable cardboard were glued on top of it, until the multi-layered cardboard cast of her buttocks was about 2.5 centimeters thick.

Here Sergio glues together layers of moist, pliable cardboard. When it is several layers thick, Mónica will sit on it so it molds to the irregular form of her backside. (Under the cardboard on the seat of her wheelchair is a thick sponge pad to accommodate the molding.)

On the cardboard mold Sergio draws an oval ring just outside the circle of lipstick marking the position of the pressure sore.

When the reinforced cardboard mold was dry and firm, the next step was to hollow-out a shallow depression directly under the location of the sore. To mark the precise location for this, her mother took the girl into a back room (for privacy) and with lipstick painted a circle around the margin of the sore. Returning to her wheelchair, Mónica was seated atop the cardboard cushion, positioning her backside to precisely fit the contours of the mold. This way a faint red-lipstick outline of the sore was imprinted on the cardboard.

As a preliminary test of its protective function, Mónica positioned herself carefully on the molded cardboard in her wheelchair, and sat there for ten minutes… after which her mother examined her backside and the sore for any signs of redness or irritation. Thankfully, no such signs appeared. So Mónica tried sitting for longer and longer. It appeared that the sculpted cardboard protected her well. To safeguard her even more, they covered the cardboard mold with a layer of soft foam-rubber.

While Mónica’s mother holds the cardboard mold, Sergio uses an egg-shaped drill-bit with tiny teeth (a tool used for sculpting), to hollow out a shallow depression slightly bigger than the sore—taking care to bevel the borders smoothly.

To firmly stabilize the saucer-shaped molded cushion within the seat of the wheelchair, they mounted it over a stout square of laminated cardboard that was notched to fit snuggly between the side-bars of the wheelchair seat. To fill in the open spaces between the curved mold and the flat base, they used a Styrofoam spray that quickly hardened to form a lightweight solid unit. (As a filler, we’d considered using paper-mache or sawdust-with-glue, but the spray-in Styrofoam was locally available, lighter weight, and relatively inexpensive.)

As a preliminary test of its protective function, Mónica positioned herself carefully on the molded cardboard in her wheelchair, and sat there for ten minutes… after which her mother examined her backside and the sore for any signs of redness or irritation. Thankfully, no such signs appeared. So Mónica tried sitting for longer and longer. It appeared that the sculpted cardboard protected her well. To safeguard her even more, they covered the cardboard mold with a layer of soft foam-rubber.

Again, the experimental cardboard cushion was tested in stages. Mónica sat on it, in her wheelchair, for longer and longer periods—taking care to lift her backside up off the chair every few minutes.

To everyone’s delight, on her new cardboard cushion Mónica sat visibly somewhat straighter, and said she felt more comfortable and secure. With her improved posture and stability she could push her wheelchair around more strongly and effectively. Both she and her mother were pleased.

|

|

|

After her new cardboard cushion was completed and tested, it was painted with oil-resistant lacquer. A volunteer seamstress made a pillowcase for it…. Also a cardboard foot-support was fitted on top of the metal-tube footrest of her wheelchair, to better hold her feet. But the wheelchair still had problems that needed fixing, such as the very low backrest (see below).

Additional Needs

There were still some technical problems, however, mainly with the wheelchair. Mónica loves her wheelchair, which looks elegant and streamlined. Branded an “Independent Living Wheelchair,” it was given to her by Independent Living International. However the chair had features that did not match her needs. Essentially it is a sports wheelchair, ideal for strong athletic users. Fortunately, it comes in different sizes. But unfortunately, the same design is given to everyone. And it comes without brakes! In the steep hilly areas of Mazatlan, for someone with weak arms such as Mónica, it’s a catastrophe waiting to happen.

Mónica felt more comfortable and she tired less quickly.

Also, the wheelchair’s backrest was very low. Mónica’s upper body, completely unsupported, angled backward awkwardly. What’s more, the back of the wheelchair lacked hand-grips for an attendant to push it… assistance that Mónica very much needs, given her frail condition and the hilly terrain. Her mother, who had to bend way over to push the very low seat-back, was developing back pain.

We urged Mónica to accept a more appropriate wheelchair, which the disabled team in PROJIMO Duranguito could design to her specific needs. But she was wedded to her elegant IL sports chair. (In the last few years in Mazatlán these swank-looking chairs have become a status symbol among disabled youth.) Finally a compromise was reached. Mónica would keep using her beloved IL chair, But Habilítate would ask PROJIMO Duranguito team to modify it so as to better meet her needs.

Amazingly—although Duranguito is more than 60 kilometers away—the team there completed the necessary adaptations from one day to the next. These changes included:

-

raising the backrest to shoulder height,

-

adding hand-grips (for attendant pushing) to the tops of the raised backrest bars,

-

adding easy-to-use hand-brakes.

When the modified wheelchair was delivered to her home the following day, both Mónica and her mother were thrilled. She found she could sit more upright and wheel it around more easily. She felt more comfortable and she tired less quickly. And of equal importance, the adaptations didn’t detract from her vehicle’s overall elegance.

Mónica’s newly adapted wheelchair with modifications to meet her specific needs. These include

- A raised backrest

- Added hand-grips at a good height for pushing by an attendant, and

- Added rear-wheel hand-brakes.

This front view (above) shows clearly the molded cardboard cushion and laminated cardboard footrest).

Mónica, her molded cardboard cushion in place, sits on her wheelchair adapted to her specific needs (raised backrest , raised handles for pushing by attendant, added brakes, more suitable footrests). With this combination of personalized adaptations, her pressure-sore healed, her posture and mobility improved, and so did her self-assurance and hope for the future.

These two photos (above) show how much better Mónica sits with the backrest raised, her buttocks evenly supported, and her feet stabilized. Not only did her pressure sore heal, but she sits in a much healthier, more comfortable position, and is able to propel her wheelchair more forcefully and with less stress.

Results

To the amazement of skeptics of “low-brow technology” for such life-threatening problems, the outcome of Mónica’s custom-molded cardboard cushion was remarkably good. The obstinate pressure sore, which for years had failed to heal while sitting on a state-of-the-art air-cushion, within days showed signs of healing when using the cardboard cushion. After four weeks the sore had almost completely granulated in… even though Mónica now spent considerably more time in her wheelchair and less time in bed than formerly. By eight weeks the the sore was completely closed with a thin layer of new, delicate skin.

There were, of course, other ameliorating factors. One was the use of bee’s honey to speed healing and reduce infection. Another was helping Mónica realize how essential it is to lift her backside up off the wheelchair seat every few minutes, to permit blood circulate in the flesh over her sit-bones. At first such lifting was very hard for her because her arms and body were so weak. But soon she began to get stronger. With her increased activity—and her improved sense of well-being—her appetite returned and she started to gain weight. Little by little she began looking to the future with hope. With the healing of her sore, she could use her wheelchair again, which was now was safer and more comfortable. She began making plans for going back to school.

There is little doubt that several factors contributed to Mónica’s rapid recovery. Perhaps part of her transformation may be explained by the fact that the folks in Habilítate, who attended to her needs in such caring and effective ways, are themselves disabled.

Please Help Spread the Word About Paper-Based Technology and Save Lives

As community-based rehab workers, we’d like to emphasize the vital role that “Paper-based Technology (PBT)” can play in the prevention and treatment of decubitus ulcers (pressure-sores). In both rich and poor countries, pressure sores are a major cause of disability and death in spinal-cord injured persons, in children with spina bifida, and in others who have conditions where feeling is compromised. The high cost of Roho cushions and similar devices is a major obstacle to the prevention and management of such sores. The fact that waste cardboard can be recycled and made into pressure-sore combating cushions could be a breakthrough to save thousands of lives. It exemplifies how certain local low-cost technologies—with sufficient caring, personalized attention—can sometimes give better results than than do mainstream high-cost options.

An Unmet need: A Drug-rehab Center that Welcomes Disabled Persons

Habilítate Mazatlán is not always successful in its intent to help its members stay off drugs. Crystal-meth addiction is notoriously hard to shake. Some of the group’s most caring and capable workers have slipped again into heavy drug use and have needed to go back into drug-rehab centers. Unfortunately, in Mazatlán—and to the best of our knowledge, in Mexico as a whole—there are no drug treatment facilities equipped for use by people with disabilities that require special accommodations.

The policy of the rehabilitation center is not to admit disabled persons who need special accommodations.

One of our wheelchair-riding Habilítate members who recently relapsed—whom here I will call José—is now voluntarily interned at the Drogadictos Anónimos center in Mazatlán. However he was accepted at this DA center only because his uncle (a former drug user) is now the secretary there. But the policy of this center—like virtually all others—is not to admit disabled persons who need special accommodations. Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán has no ramps, so José must be manually carried up and down steps. Likewise, the bathrooms are not wheelchair-accessible. Housing laws are another concern. Because the center fails to meet regulations for disabled residency, every time an inspector shows up, José (or at least his wheelchair) has to sneak away into hiding.

Given the vast unmet need for drug centers that are willing and able to serve disabled people, members of Habilítate recently met with board members of Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán to explore the possibilities to adapt the center for legal accommodation and friendly inclusion of disabled persons. To meet state requirements, this will mainly entail building a few small ramps and making at least one bathroom wheelchair accessible. In all, it shouldn’t cost more than US$2,000.

HealthWrights has agreed to try to raise the money to put into operation what we believe will be the first drug-rehab center in Mexico that is specifically equipped and committed to welcome recovering addicts who are also disabled.

The Drogadictos Anónimos Mazatlán center is one in a chain of 37 such centers throughout Mexico. If the Mazatlán branch can transform itself into a disability-friendly facility, it could become a catalyst for far-reaching change. With encouragement others may follow suit. The time is propitious, since “disability rights” are currently a prevailing concern internationally.

In the US, donations made through HealthWrights are tax deductible. Click here for more info.

Do You Want To Study Spanish Online?

Rigo Delgado, who helped facilitate the Child-to-Child program described in this newsletter (and also the subject of Newsletter #68) is again offering basic and conversational Spanish classes by Skype, To see the announcement, click here.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |