Inclusion of the Most Excluded—‘The Power of String’: Update on the Buddy Home Care initiative in Ubon, Thailand

As was described in Newsletter #81, the Health and Share program in Ubon was originally initiated by a Japanese NGO (non-government organization) called SHARE. Today the Health and Share Foundation is completely independent from its parent organization and is run by a collective of dedicated Thais.

Health and Share, like its parent organization SHARE, has a down-to-earth, egalitarian philosophy of “putting the last first.” The relationship between Health and Share and SHARE remains close.

SHARE—which was founded and is led by Dr. Toru Honda, a pioneer of comprehensive Primary Health Care—has helped build community-run programs in a spectrum of Asian and African countries.

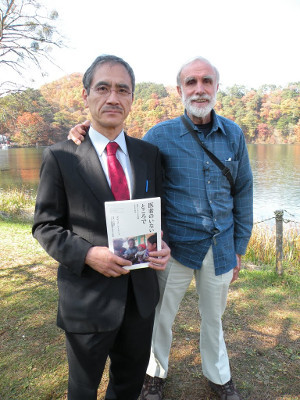

Toru and I have see eye-to-eye on many matters of health, human rights, and defense of the underdog. Over the last two decades his program has welcomed me to do workshops, consultancies, and seminars in East Timor, Thailand, and Japan. Meanwhile SHARE has produced a Japanese translation of our book Questioning the Solution, the Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival, by David Sanders and myself. Also this year (2018) SHARE has translated into Japanese an updated edition of my village health-care handbook, Where There Is No Doctor (now in nearly 100 languages).

The community health program in northeast Thailand was initiated by SHARE as a comprehensive Primary Care endeavor focusing on prevention and treatment of the common “diseases of poverty.” But soon, at the request of the local villagers, the program shifted its primary focus to the escalating, much feared problem of HIV-AIDS … and from there forward, on the needs, inclusion, and enablement of the most stigmatized and marginalized groups. These stigmatized groups include the gay and transsexual community, street children, sex-workers, and destitute immigrants from Laos and other neighboring countries. Members of these groups today play a leading role in the program.

SHARE includes stigmatized groups: the gay and transsexual community, street children, sex-workers, and destitute immigrants.

The Buddy Home Care initiative was conceived by HSF in 2016 with the aim of reaching out to two very vulnerable groups: 1) children in very difficult circumstances, and 2) elderly people with chronic illness or disability. The Buddy Home Care initiative tries to respond to the needs of these highly vulnerable populations by recruiting some of the children to become co-helpers or “buddies” of the local home-care-providers in their home visits. With their home-care-provider “buddy,” the kids regularly visit, befriend, and assist an ailing, often lonely elderly person in their neighborhood. In the process, the elderly person and child frequently form a close, mutually supportive bond. Through this process, the vulnerable child becomes an ally or “buddy” of both the individual home-care provider and the elder-in-need: a win-win-win combination.

Since I last visited Thailand a year-and-a-half ago, the Buddy Home Care project has broadened its outreach to include diverse members of the community through a participatory process of awareness-raising, so as to encourage shared concern and inclusion. I learned about new developments in a recent letter from Dr. Toru—who had joined me in my visit to Ubon-Rachathani in May 2017—after he returned from a more recent visit to Thailand in August 2018.

In his letter to me, Dr. Toru described one of the new awareness-raising activities facilitated by Health and Share. This activity was a role-play mysteriously called “The Power of String.” Dr. Toru enclosed a writeup on this role-play, with photos, prepared by “Cherry,” the director of the Health and Share Foundation The following observations are pieced together from Cherry’s writeup and Dr. Toru’s letter.

Before the “The Power of String” role-play began, an “icebreaker” exercise was facilitated called “Talking Up and Talking Down.” Workshop participants divided into pairs. In each pair one person sits on the floor while the other stands over him/her, and they talks to each other. This way one person “talks up” and one “talks down” to the other. Next, both persons are asked to sit on the floor and continue talking to each other—now on the same level. The exercise ends with a group discussion about how the participants felt in the different positions, and how this dynamic compares to feelings of equality and inequality in real life situations. This exercise sets the stage for the role-play that follows.

“The Power of String” role-play is about teenage pregnancy. Participants in the workshop—who include health and social workers, and pairs of home-care buddies—play the roles of different members of the community. These roles include health volunteers, heads of villages, health staff, parents, teachers, and others who have been in positions of power over the children in the village for some time. This activity aims to let the pairs of “buddies” know how much stigma can hurt someone.

I include a slightly edited section of the letter where Dr. Toru Honda writes about the “Power of String” role-play:

This time around I had a chance to observe, in Khemarat district, a Buddy Home Care workshop on parental awareness-raising with regard to teenage rage, bullying, substance abuse, smart-phone addiction, and pregnancy…. Such problems are rampant, I believe, in the US and Japan, as well.”

One quite interesting role-play was a situational mini-theater on teenage pregnancy.

The key subject in the skit—played by a youth-group leader—was a pregnant secondary student, sitting in the center of the circle. Surrounding her is a group of [participants/actors representing] about 20 villagers, whose jobs/relationships are so varied—from village headman, hospital doctor, health center nurse, city council member, to her father, mother, grandma, grandpa, sisters, brothers, aunt, to school teacher, officer of social welfare department, and so on. During the first scene everyone is severely critical and reprimanding of the girl, saying, “You’re a disgrace to the community, to the family, and to the school.” Every time she becomes the target of an unkind, chilling remark, the girl’s body is bound by a plastic string. In the end her body is completely wrapped up by 20 or more strings.

The girl’s complexion was tense and hopeless, even in the theatrical context.

Then in the second scene, the people gradually change their mind. There comments change, according to Cherry from “negative to positive.” … People around the girl become mellow and accepting, saying such words as, “If you want to return to school after the baby is born, you are welcome,” (said by the school teacher). Or, “Please come visit the ANC [antenatal clinic] (said by a health-center midwife).

After all the strings are removed, the girl and the “villagers” (played by the workshop participants) gather together and discuss what they have felt in Scene 1 and how their mindsets have changed in Scene 2.

Dr. Toru concludes:

That was really a moving experience for me to see this role playing. I hope my clumsy English can convey to you some flavor of this mini-drama.

Cherry, in her summary of the activity, provides the following conclusions:

The activity let the villagers express their feelings, both negative and supportive, about about teenage pregnancy in their community. The bad words they spit out hurt vulnerable children much more than console them. It closes the door to listening rather than solving things together. Participants could compare these negative feelings with the positive ones, which are better to hear.

When there are much more negative feelings it makes more stigma and discrimination against the teenager. At worst, it could make the children commit suicide.

To resolve the problem of children like this, we have to reach out with the people who live in the surrounding community as well.

The pair of buddy-home-care agents [adult home-care-provider and their young companion] who work with the vulnerable need to provide positive support without judging, and must be sensitive to language that stigmatizes and discriminates.

The negative attitude could make [the pregnant girl] refuse to accept health care services.

In sum, the Power of String activity helps everyone recognize that a person’s health and well-being is not just a question of the physical and mental health condition of that individual, but depends a great deal on the attitudes and treatment by those who surround her. Providing good health-care requires a caring community. The activities of the Health and Share team are in many ways helping to build the kind of community that is needed.

Urgent request for electric wheelchairs

While the PROJIMO community-based rehab programs run by disabled villagers in Mexico make individualized wheelchairs for children and adults who need them, some of the leaders and former workers in these programs now need electric wheelchairs. Please help provide them if you can.

Companions in pressing need for an electric wheelchair include:

Virginia, who was born with brittle-bone disease (osteogenisis imperfecta), first came to the PROJIMO (Program for Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) when she was 4 years old. Years later she became a worker at PROJIMO, running the program’s cybercafe and teaching computer skills to village children. She also taught Spanish-as-a-second language to volunteer rehab workers visiting the program. Now in her mid-30s, Virginia has a teenage son José Carlos who from early childhood has helped his mother in many ways and wants to become a nurse. Virginia currently has a job as bookkeeper in a furniture store at the far end of the village (Coyotitán). To get to the store, however—because of her fragile, twisted arms (from repeated fractures)—she needs someone to push her manual wheelchair. This job usually falls on José Carlos, though the timing often conflicts with his school schedule. For greater independence, Virginia very much needs a (small) electric wheelchair.

Conchita first came to PROJIMO as a teenager 36 years ago after a fall that left her paraplegic. She has been active in the rehab program ever since, and now—in her mid-50s—is the program’s dynamic coordinator. She has two lovely daughters, now grown up and independent. Conchita has always been strong and very capable. For a while she worked making artificial limbs in the PROJIMO shop. Five years ago, however, Conchita developed breast cancer. One breast was surgically removed together with lymph nodes in her armpit and upper arm. This has weakened that arm that so much that propelling her manual wheelchair for any distance has become difficult and painful. For the active life she leads, Conchita now longs for a (wide) electric wheelchair.

Rigo became quadriplegic in a car accident when he had just finished prep school, and was brought to PROJIMO Coyotitán for rehabilitation and treatment of pressure sores. Like Virginia and Conchita, he eventually became a member of the PROJIMO team—and finally a leader. Rigo organized an outreach program to other villages, to promote awareness of disability and inclusion. Rigo went on to study social psychology at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, where he played a key role making the university physically and socially more accessible to disabled students. He likewise began a disability “Child-to-Child” awareness-raising program in village schools in migrant-farm-worker settlements nearby—for which he received national awards. For these activities, Rigo—whose four limbs are paralyzed—needs appropriate mobility aids. Friends of HealthWrights managed to get him a donated electric wheelchair and also an adapted van with a power ramp. But now both the chair and ramp are on their last legs. So for Rigo we are looking for a donated (large) power wheelchair.

For Rigo we are also looking for the donation of an adapted van with a ramp, in good condition. And if possible, a volunteer driver to drive it to Sinaloa, Mexico. (The wheelchairs we can fly down.)

IF YOU CAN HELP FIND OR DONATE WHEELCHAIRS FOR THESE COLLEAGUES, PLEASE DO!

Wheelchairs can be sent or delivered to:

Healthwrights

c/o Jason Weston

3897 Hendricks Road

Lakeport CA 95453 USA

Help Needed—Give a child a customized wheelchair!

Over the last 15 years the team of disabled crafters in the village workshop in PROJIMO Duranguito, Sinaloa, Mexico, has been making individualized wheelchairs for disabled children—designing each chair both to the child’s combination of needs and to his or her local environment.

Stichting Liliane Fonds has now pulled out of Mexico.

Thanks to generous support from Stichting Liliane Fonds, a charitable foundation in Holland, the village team was able to provide these wheelchairs and other assistive equipment to disadvantaged children free or for a small fraction of the costs. And this individualized approach has spread to other programs and countries. The chairs cost from around US$250 to $350 each.

Unfortunately, however, Stichting Liliane Fonds has now pulled out of Mexico. This not only makes it more difficult to provide specially-adapted wheelchairs to the many children who need them, but also the jeopardizes the self-reliance of the disabled craftspersons who make the chairs.

Click here to learn more about how you can help!

End Matter

Do You Want To Study Spanish Online?

Rigo Delgado, who helped facilitate the Child-to-Child program described in this newsletter (and also the subject of Newsletter #68) is again offering basic and conversational Spanish classes by Skype, To see the announcement, click here.

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |