David Werner receives honorary doctor degree in Mexico

On June 20, 2023, the Autonomous University of Sinaloa (UAS), in the state capital of Culiacán, Mexico, awarded me, David Werner, an honorary doctorate (Doctor Honoris Causa) in recognition of the “many years devoted to helping people in the Sierra Madre of Sinaloa and worldwide improve their well-being” and for the self-help books I have written.

The university made the occasion a tremendous event, announcing the award via radio, TV, internet, posters, flyers – and on huge roadside espectaculares (billboards) displaying a photo of me with the rector of the UAS. These imposing billboards were placed not only in the state capital of Culiacán, but also in key locations in Mazatlán, Los Mochis, and other cities in Sinaloa where the state university has outlying campuses.

The event itself was on a grand scale. The 600-seat auditorium was filled to overflowing. Behind a 30-foot table on the stage sat a row of elegantly clad dignitaries. I was positioned to one side, dressed-up like an elegant clown, in a hand-woven guayabera (a pleated shirt), a flowing purple gown, and large purple cap with golden streamers.

The ceremony began with a parade of lovely young women clad in military attire, marching to the blare of a marching band. This was followed by the Mexican National Anthem, to which everyone (who could) stood up to sing with outstretched arm in salute. Then came a sequence of laudatory speeches.

At the given moment, the rector of the university, Jésus Madueña Molina, hung an enormous gold-colored medal around my neck and handed me a handsomely-framed diploma certifying my honorary degree. I had to chuckle to myself at the formal photograph of me on the certificate, which had in its way – like me – been “doctored.” Because no one had been able to find a photograph of me dressed up in a coat and tie (I haven’t worn a tie in over 70 years, as a matter of principle) the university’s graphic artist had adroitly spliced an image of a suit and necktie onto an amputated photo of my head. I haven’t looked so conventional in years!

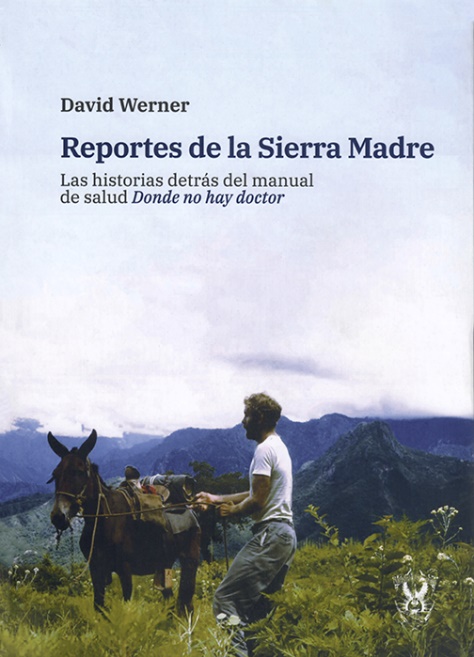

After the award ceremony was over, I spent more than two hours signing copies of the new edition of the Spanish version of my new book, Reports from the Sierra Madre (see below) and of the recently revised Spanish edition of Where There Is No Doctor.

Other events peripheral to main ceremony

In relation to the awarding of the honorary doctorate, two other festive events preceded it.

Commemorative festival in Ajoya

The first of these was a commemorative festival, on June 19, in the small village of Ajoya, which for decades was the base for Project Piaxtla, our campesino-run health program serving the Sierra Madre, and for PROJIMO, the community-based rehabilitation program led by disabled campesinos. It was a joyful event, held out-of-doors in the evening, with lots of traditional music and dancing, storytelling, and skits – with exuberant participation by the village children.

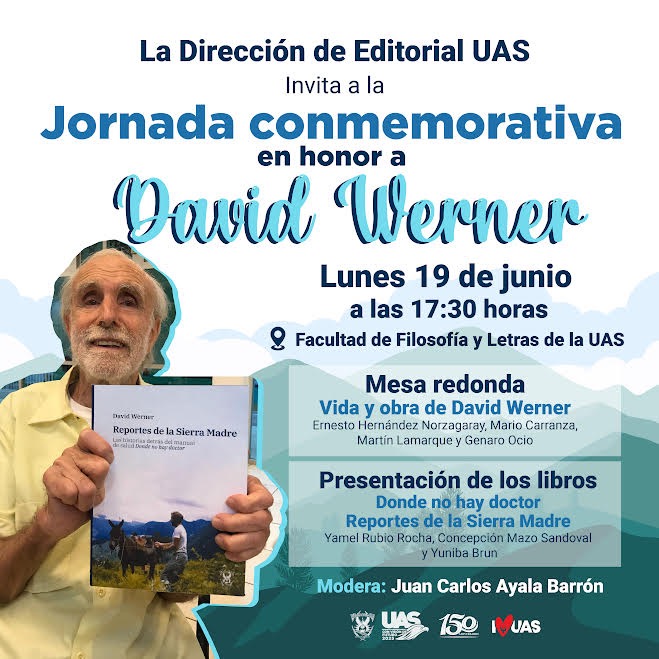

Roundtable and book celebration in Culiacán, June 19

The day before the grand honorary doctorate ceremony on a smaller preliminary “roundtable” had been organized by Editorial UAS, the university press, which just a few months before had published a high-quality edition, in Spanish, of Reportes de la Sierra Madre. To this June 19 roundtable, the organizers had brought in selected speakers deeply familiar with my work and writings.

One of the speakers, who came all the way from California, was Martín Lamarque. Born in the town of Coyotitán, Sinaloa, as a youth Martín volunteered for years in PROJIMO. Later he helped translate into Spanish my handbook Disabled Village Children.

Another speaker was Genaro Ocio, who as a boy growing up in Ajoya helped in our village rehabilitation program, and as an adult led the restoration of the village and of the community clinic, with its commitment of putting the neediest first. (See our Newsletter #87)

Yet another of the speakers was professor and author Ernesto Hernandez Norzagaray, who grew up in the backcountry of the Sierra Madre and has long been familiar with our innovative health and disability activities in that remote region.

Moderating the roundtable was Juan Carlos Ayala, director of Editorial UAS, whose leadership and enthusiasm made possible the publication of Reportes de la Sierra Madre by Editorial UAS.

Heartfelt reunions

One on the things I enjoyed most about the well-publicized event of the honorary doctorate was the opportunity it gave me to meet lots of old friends, some of whom I hadn’t seen for years or even decades. Some had traveled from distant states. Many were disabled people – some in wheelchairs or on crutches – who had gone to PROJIMO for rehabilitation as children.

José Antonio

One of the old friends with whom I was overjoyed to reconnect was José Antonio Nuñez, whom I’d first met as a slender, spritely seven-year-old nearly half a century ago! He is now age 59. When he approached at the ceremony last June, I didn’t recognize him – until he rolled up his sleeve and showed me the big scars on his upper arm. “José Antonio!” I exclaimed, and we threw our arms around each other.

It was a joy to me to cross paths with José Antonio again after so many years, and see he is using so well the arm he almost lost as a child, due to cancer.

When he was eight years old, José Antonio had been diagnosed with bone cancer in his upper arm. Doctors in Mazatlán said it was so advanced that the arm had to be amputated. I sent X-rays to the doctors at Shriners Hospital in San Francisco, who said they might be able to save his arm. However, to get him into the United States there was a problem. We had to obtain his birth certificate, which was in the town office of the distant village of San Juan, where he was born, upriver at the end of a long dirt road. To obtain his certificate, the boy had to present himself in person. His mother said that would be too dangerous! Three years before, in San Juan where they then lived, the boy’s father had been killed by the notorious local drug lord, called El Cochiloco (The Mad Pig). The boy’s mother with all her children at once moved away, to San Ignacio, to protect her children – in particular her sons. This was because, when El Cochiloco killed someone – he and his gang are said to have killed over 100 people in San Juan alone – he had the habit of also killing his victims’ male offspring – because he was afraid that when they grew up they might seek to revenge their father’s death.

So, what to do? One way or another, we needed the birth certificate. I offered to drive José Antonio to San Juan. He could hunker down in my car and no one would recognize him – we hoped. His mother, with misgivings, gave permission.

We arrived in San Juan, covered with dust, and managed to get the birth certificate without incident. However, on the return drive, we had a scare. Coming around a bend on the dirt track, we saw a big black pickup truck coming our way. It looked like an angry porcupine, there were so many rifles and R-15s poking up from it. The pickup stopped in the middle of the road, blocking us from passing by. Two men with weapons drawn approached our vehicle. “Who are you and where do you think you’re going?” they asked angrily. I told them I was the gringo curandero from Ajoya and explained that the youngster with me had bone cancer, and that I was arranging to take him to San Francisco for surgery. They wished us well and we continued on our way.

A few weeks later, we were at Shriners Hospital in San Francisco. The medical team examined José Antonio. The cancer had already invaded over half the width and nearly the full length of his right upper arm-bone. The chance of saving the limb was doubtful, the doctors said, but it was worth a try. So the surgeons proceeded with the difficult operation. Thankfully, it proved successful. Though only a thin strip of healthy bone remained after surgery, and the boy had to be very careful not to stress it for several months, the bone gradually grew thicker and stronger. Now, decades later, José Antonio works as a delivery man, driving a truck and lifting heavy packages with ease. His right arm is as strong as the left.

During all the long ordeal to save his arm, José Antonio and I had become very close. So it was a joy for both of us to renew our friendship on the occasion of the UAS award ceremony.

Lilí Chaides

Another longtime friend who is disabled came to the award ceremony from far away: Lidia (Lilí) Chaides, traveled from Los Mochis, accompanied by her husband Victor, also a wheelchair rider. Decades ago, we helped attend Lilí’s urgent rehabilitation needs at our small rural health center in Ajoya. A car crash in her teens had left her quadriplegic (paralyzed from the neck down).

By the time her family brought her to PROJIMO several months later, Lilí was still unable to do much of anything for herself, had developed deep pressure sores, and was close to suicidal. But in PROJIMO little by little – thanks to the care (and role model) of two of the program leaders, Mari Picos and Conchita Lara, who likewise were spinal cord injured – Lilí made steady improvement, both in body and spirit. Her pressure sores – packed with honey daily – gradually healed. Soon she learned skills to manage many of her daily needs. By the time she returned home, she was ready to face the daunting challenges imposed on her by her compromised physical condition, and animated to move ahead with her life.

Through the decades that followed, we stayed in touch with Lilí intermittently and followed her amazing course of life. Despite her physical limitations, she studied to be a social worker, then got a job at DIF (a government program serving families with special needs). In that capacity she collaborated with PROJIMO Duranguito, a branch of our rehab initiative that makes customized wheelchairs for disabled kids. Thanks to her care in scouting out those in need, Lilí facilitated more 100 children receiving wheelchairs, individually designed to meet their specific needs.

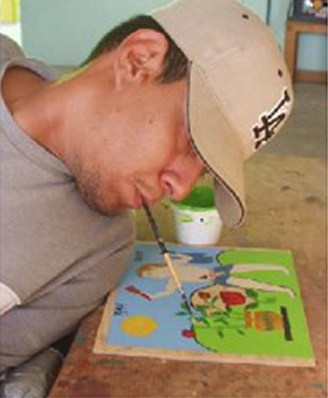

After her fateful accident, Lilí developed many outstanding abilities. She became adroit at painting pictures with her mouth, and in time has become an acclaimed artist. Now a key member of the International Mouth and Foot Painters Association, she teaches the art of mouth-painting to more than 20 quadriplegic apprentices in the Los Mochis area.

One of those to whom Lilí introduced to the art of mouth-painting is Gabriel Cortes – a longtime ally of ours, whom she got to know in PROJIMO long ago when both were there for rehab. Function-wise, Gabriel is in effect quadriplegic. He was born with arthrogryposis, a congenital impairment where all the joints of his extremities are deformed and stiff. He cannot sit or eat or bathe without assistance. Yet he drives his motorized wheelchair up and down the malecón (beach promenade) like a demon.

Gabriel is happily married and is fiercely his own person. Similar to Lilí, he has had award-winning exhibitions of his unique, highly varied paintings, and earns a modest but steady income through their sales.

Gabriel is a co-founder and for the last six years has been the elected president of Habilítate Mazatlán (Enable-Yourself Mazatlán), a small non-profit service program organized and run by disabled persons, most of whom are trying to get off and stay off drugs. They make high-quality, individualized special seating (mostly out of cardboard!) and other assistive equipment for disabled kids with difficult positional needs. The quality and attractiveness of their works has won wide acclaim. The community’s appreciation of their work lifts their own self-esteem, thereby helping them stay off drugs. (See our Newsletter #82.)

During the event of my award, Lilí publicly presented me with one of her splendid mouth paintings: a whimsical portrait of me! The painting delights me because it captures a wry sense of humor in my expression, a look of critical bemusement. Her painting now hangs on my bedroom wall in El Tablón, next to – and apparently gazing at – my framed diploma with its “doctored up” photo of me decked out in a Photoshop-inserted coat and tie. I love this amusing juxtaposition!

Liaison with a gung-ho disability and human rights activist from Jalisco – sparking new projects and possibilities

Good things often happen fortuitously. I had gotten to know Juan Lopez, because his son Tomás and I share the same disability, CMT – see Newsletter #79. A few months ago, Juan linked me up with an old friend of his since childhood: Juan Antonio Heyer Banda, who lives in a village near Guadalajara. Juan Antonio has now become closely involved with our disability-related work and has opened up exciting new collaborations from his deep knowledge and experience with high-level spinal-cord injury.

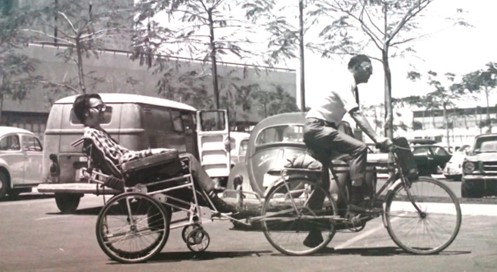

A year ago, Juan Antonio shared with me the working draft of a captivating book he has written titled ARTHUR HEYER, A PRODUCTIVE LIFE without moving a single finger. This is the inspiring story about his older brother, Arturo (Arthur), who at age 17 became a high-level (C3-C4) quadriplegic, as result of a fluke accident. On a hot summer’s night, he crept out of the house and in pitch darkness and dove into a neighbor’s deep tank of water, which – unbeknownst to him – had just been drained. Crashing onto the cement bottom, he broke his cervical vertebrae and became completely paralyzed from the neck down. For life.

In the weeks following the accident, Arturo nearly died from severe pressure sores and urinary infections, which developed while he was still in the hospital. Eventually the hospital sent him home to die. But miraculously – with the help of his loving, creative, and highly supportive family and despite being totally paralyzed below his neck – Arturo went on to lead an exceptionally productive and, in many ways, happy life. He completed prep school and then got a degree in engineering from the Autonomous University of Guadalajara.

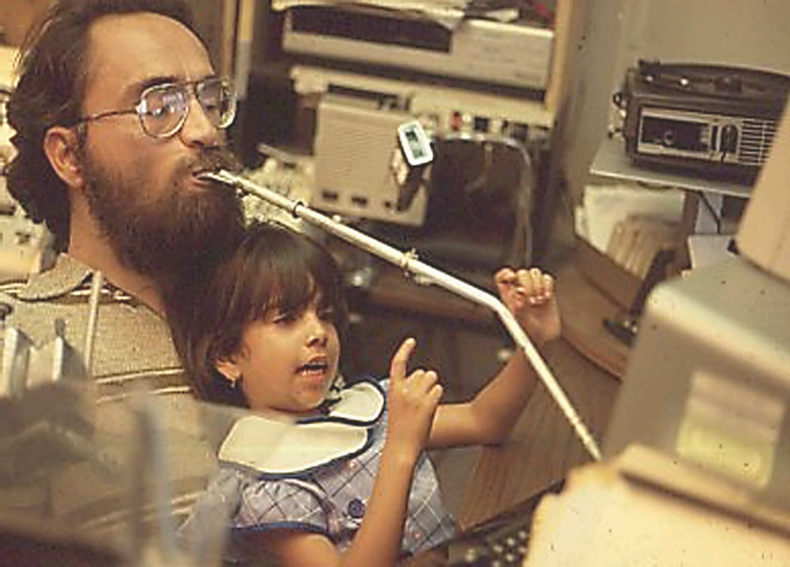

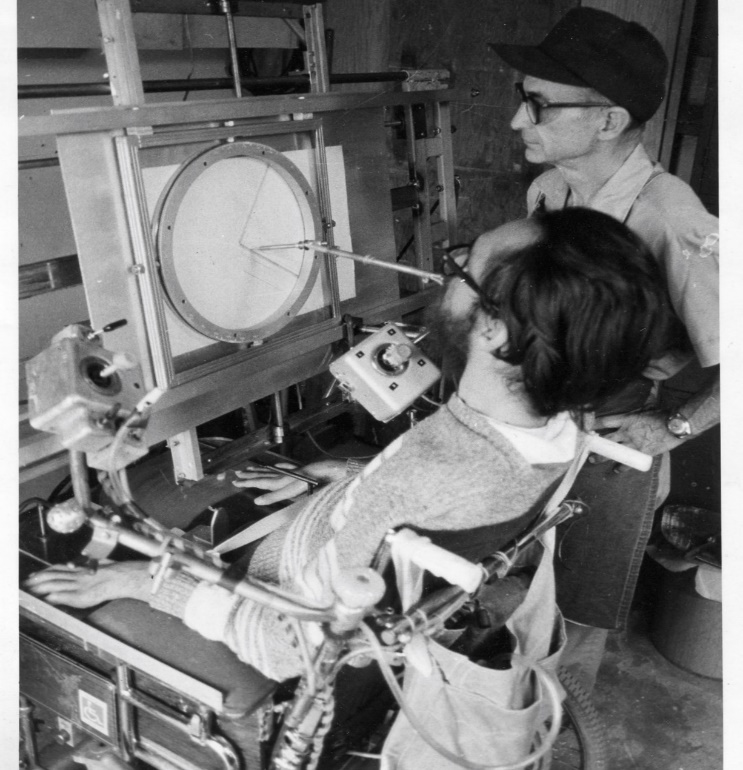

With his father’s and siblings’ unstinting support and encouragement, Arturo designed a large variety of clever tools and assistive equipment. Using a unique and very versatile mouthstick to shift the positions of his Dr. Suess-like rotating desk that he’d invented, he mastered a range of practical and creative activities, all manageable with a wide assortment of mouthsticks.

When we told Juan Antonio about our quadriplegic friend Lilí, who – similar to his brother Arturo – has led an amazingly productive life, Juan Antonio took off for Los Mochis to meet her. They quickly became good friends. Impressed with the quality and diversity of her mouth-paintings, on his next visit he gave Lilí one of his brother Arturo’s battery-run, pushbutton-operated operated easels – which is positioned so she can control it by pushing with her elbow. Lilí is thrilled with the easel, which allows her to move her canvas in all directions so she can paint independently without need of a helper to constantly reposition her painting-in-progress. (See videos one and two of Lilí painting with her new easel.

Now Lilí is eager that each of her quadriplegic mouth-painting trainees have their own pushbutton-adjustable easel and is committed to collaborate in our proposed project to produce and distribute them.

Regarding Arturo’s inventions, for years it was his kid brother Juan Antonio – 13 years old when Arthur broke his neck – who devotedly helped construct the prototypes of these ingenious devices. Arturo designed them for his own use. But he soon realized they also worked well for his quadriplegic friends. Clearly there was a large unmet need for such gadgets – none of which were then available on the market. So Arthur finagled a grant and started a small business to produce quantities of these devices. They ranged from multipurpose mouthsticks to rotating multitask desks, to pushbutton-adjustable easels, to adapted typewriters, and much more. Since there was nothing equivalent on the market, in the US Medicaid and Medicare stepped in to cover the costs for qualifying persons with disabilities. So for years Arthur was able to help meet the needs of a select clientele internationally, while (barely) making enough to cover his costs.

Arthur’s main goal was not to make money but to serve those in need. For this reason, he never applied for patents on any of his inventions. With a motley team of workers – many of them down-and-outers who needed a job – Arturo managed the production of these unique devices until shortly before his death in his mid-sixties.

Plans for inter-program collaboration to make and distribute Arthuro’s devices

Currently, PROJIMO-Duranguito – together with Lilí and her coterie of “quads” in Los Mochis, Habilítate Mazatlán, and ARSOBO (a rehab program of disabled workers in Nogales, Sonora, modeled in part after PROJIMO; see our Newsletter #78) – are working together to launch a new, highly innovative venture.

Also, preparations are underway to renovate the former wheelchair workshop in Ajoya, so that in addition to building low-cost hand-powered, electric-motor-assist tricycles, possibly Arturo’s adjustable easels can also be made there, in partnership with the groups mentioned above.

If this collaborative venture gets off the ground, entailing the creation of ingenious devices to help facilitate the fuller independence of people with disabilities to realize their unmet potentials, this may be the subject of a future newsletter.

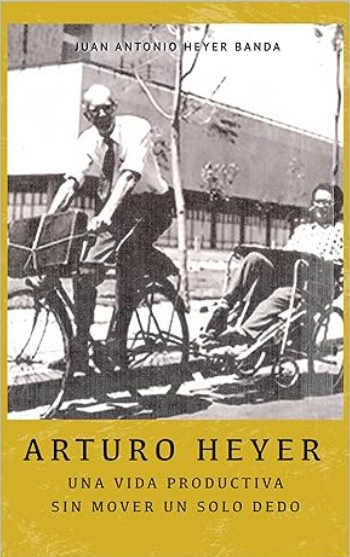

Announcing an astounding new book about Arturo Heyer, by his brother Juan Antonio Heyer

When Juan Antonio Heyer first came to visit us in Sinaloa a year or so ago, he was working on a book about his quadriplegic brother Arturo’s stunningly productive life. His book is titled, ARTURO HEYER – UNA VIDA PRODUCTIVA sin mover un solo dedo (in Spanish), and ARTHUR HEYER – A PRODUCTIVE LIFE without moving a single finger (in English).

This gripping narrative is enlivened by a wealth of revealing photos and instructive drawings. Juan Antonio Heyer covers not only the pragmatic creativity of his brother Arturo and his remarkable family, but he also meticulously provides design and operative details for many of Arturo’s assistive devices.

Published after years of preparation in November 2023, the book is available through Amazon in both English and Spanish, as a paperback and digitally on Kindle. (For details, see below.)

To me, it is crucial that this account of Arthur Heyer’s life be widely known. For the general reader it will provide an enlightening, heartwarming story. But for persons with a major physical disability, their family members, and for the providers of rehab services or occupational therapy, it will be a profound eyeopener – a game-changing tool.

Too often persons who are extensively disabled are treated with condescension, with pity, or with dependency-creating care, but with little hope they will ever lead full and productive lives. For such extensively impaired persons, the story of Arturo can be truly liberating in that it opens a panorama of new perspectives and unimagined possibilities. This inspiring saga of Arturo Heyer and his family can help trigger a greatly needed change in perception and open new horizons for a marginalized group of people with high potential.

With confidence that it can have an enabling impact, I am committed to do what I can to see that Juan Antonio’s newly released book-from-the-heart reaches a wide audience, so it can make the greatest difference in people’s lives. Above all, I hope it reaches those who may most benefit from it, or who – by broadening their perspectives – may benefit others. At Juan Antonio’s suggestion, I gladly wrote a prologue and helped with the editing.

Since Juan Antonio Heyer is fluently bilingual (his father was half gringo), he wrote both the Spanish and English versions of these memoirs himself. As result, the English has some flavorsome mexicanismos that I was glad to see preserved. Nonetheless, the manuscript had places where, for sake of clarity, a bit of editing was needed. My dear friend Bruce Hobson, longtime board member of HealthWrights who in his youth volunteered with our projects in the Sierra Madre, carefully went over the text to clear up any unclarities, while preserving its sincerity and sabor latino.

Fortunately, a number of possibilities for the book’s dissemination have been emerging. We are contacting friends in various disability organizations, such as Rehabilitation International, World Institute on Disability, Independent Living Movements, and Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) initiatives. Of those we have notified, most have been highly enthusiastic. A disability-educator friend of mine, Teresa Zorrilla, feels Arturo’s story is so fascinating and important, she is exploring ways to have it made into a movie.

PLEASE HELP SPREAD THE WORD! If you have contact with persons or organizations who might be interested in this astounding new book, or in helping disseminate or promote it, please spread the word.

How to get this book: The paperback edition of Arthur Heyer: a Productive Life, without lifting a single finger is available in English or Spanish, from Amazon. Price for either is $14.99 (paperback) or $9.99 (Kindle).

Donations and Assistive Equipment Needed for Disabled Colleagues

For Rigo Delgado (quadriplegia) – longtime activist with PROJIMO and Child-to-Child workshops (see Newsletter 85); now counselor at Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa. He needs van with wheelchair lift – or funds to buy one.

For Gabriel Cortes (arthrogryposis) – director of Habilítate Mazatlán (program run be disabled persons who make assistive equipment for disabled children (see Newsletter 82). Needs wheelchair lift – or funds to buy one.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |