Recent adversities and challenges

Along with some good news to follow, this newsletter first addresses some recent adversities and challenges faced by families in central Sinaloa, Mexico—along with collective action taken by local communities to endure. Then it relates news about the programs we’re involved with in Mexico, and tells the inspiring story of how a disabled boy we helped as youngster, now middle aged, is warmly returning the favor, as a care provider for me.

Another harrowing adversity in Sinaloa (and much of Mexico) has been the regional increase in violence. In large part this stems from the escalating war between powerful drug cartels. (The Durango Cartel is battling to seize the turf of the Sinaloa Cartel.) While most of the fighting is between conflicting gangs, too often innocent people are caught in the crossfire and lawlessness. Ordinary people fear to leave their homes, plant their fields, or go to work. Many shops and services have shut their doors. Even schools are abruptly closed for days or weeks. The new pro-people Morena national government is now much less in cahoots with the drug gangs than previously regimes, but less heavily armed than they are. And still, powerful military-grade weapons pour into Mexico from the United States with very few restrictions or controls. And Mexico continues to have one of the highest civilian death rates in the world.

These mounting difficulties and challenges call for action by the villager-run health and rehabilitation initiatives with which we collaborate. As ever, those hardest hit by these overarching adversities—be they climatic or social—are the poor and marginalized, both in urban and rural areas.

In brief, the contents of this newsletter include:

-

1st. Local efforts to cope with the effects of climate change. Some of the more daunting of these adversities are related to climate change, which is hitting west-central Mexico with a vengeance. Every year the scorching temperatures get worse and worse and rainfall more sparse and erratic. At lower elevations during the spring dry season, temperatures can surpass 110° Fahrenheit. For poor families without air conditioning or even electricity, bare survival can become a real challenge.

For the community-based initiatives we collaborate with in Mexico (the two PROJIMOs and Habilítate Mazatlán) these current life-compromising conditions have obligated these programs to reassess their priorities and to go back to basics in terms of addressing essential needs. Like water. In this newsletter we relate an example of an ongoing initiative to provide desperately needed water in a village where wells are going dry.

-

2nd. Disabled village boy becomes skilled personal care provider. The main entry in this newsletter is the moving story of a village boy disabled by hemophilia who grew up to become head nurse in Mazatlán’s first hospice program, and who currently has become a very able and devoted personal care-provider for yours truly (David Werner).

-

3rd. Update on the programs in Mexico.

- PROJIMO Coyotitán

- PROJIMO Duranguito

- Habalítate Mazatlán

-

4th. Pre-announcement of a new art book

Combating water shortage at the village level

As average temperatures of planet Earth persistently rise with global warming, different areas of the planet are affected differently, and the prognosis in different regions varies considerably. One area predicted to be hit hardest and earliest is west-central Mexico, where rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall are predicted to leave the countryside increasingly parched—to the point where shortage of water will make agriculture increasingly precarious and finally impossible. Already, as the water table drops, campesinos have to dig their wells deeper and deeper. The wealthy big landholders can use costly rigs to drill very deep wells and keep farming, at least for the time being. But for poor farming families—the majority of people in the rural areas—such costly measures are beyond their means. Already a lot of campesinos, stricken by increasing crop failures, have fallen into the perilous cycle of borrowing from loan sharks, forfeiting their land as payment, then moving to the slums of the cities, where they compete for menial jobs, send their children out begging or selling their bodies, or join the drug gangs. There are no easy answers to these problems. But folks have been taking a variety of coping measures to get by, for the time being.

One such coping measure is currently taking place collectively in the village of El Tablón Viejo. Polo Ribota—a longtime participant in our community rehabilitation and health projects—a number of years ago, built an ecology-sensible house for me next to his family’s, so they could care for me in my old age. In 2023-2024, Polo organized friendly neighbors in El Tablón to help a collective of displaced indigenous squatters. These tribal “indios”—who’d been forced off their lands by drug growers—had settled in El Tablón, where they subsisted in makeshift lean-tos and shacks. To help them better their situation, Polo mobilized local farmers to help the newcomers to cooperatively build small but adequate houses to live in.

But presently, due to the rising temperatures and diminishing rainfall, the newcomers—and the whole village—face serious water shortage. The community well, from which water had been reliably pumped for decades into an elevated tank to supply most of the village, has now virtually run dry. To solve this, at least for the time being, Polo has organized his fellow villagers to dig a new larger, deeper well, with hopes it will keep on filling the community tank for a number of years. This project, however, has proved far more challenging than anticipated. The big new well—two meters across—had to be dug more than 15 meters deep in order to provide a steady supply of water.

The digging, for the first few meters, went fairly smoothly. But the deeper they went, the denser the soil became, until it turned into a thick substrate of tacariguay (decaying granite), for which chisels and hammers had to be used. It was slow and tedious work in temperatures over 100° F. Then, at about 8 meters deep the substrate became so dense they had to rent a jackhammer.

The digging was going well. But then they ran into an enormous rock more than a meter across, right in the middle of the hole. They tried to break it up with the jackhammer—until the it broke and they had to rent a bigger one. Then they had to haul the huge pieces of rock out with a long rope—a perilous task! Since about 5 meters (about 15 feet) deep, water had already begun to trickle into the hole. They had to steadily pump it out in order to keep digging.

As the well got deeper and deeper, the inflow of water increased. At 11 meters deep, some of the workers felt the inflow was sufficient. But in hopes of realizing a reliable water supply longer into the future, Polo insisted on digging still deeper. After several more weeks of grueling work, the well was finally completed—at 15 meters deep.

Finally, pipe was laid to pump water to the community water tank. And at long last the village had a sufficient water supply—at least for the present. It was a time for celebration.

Going full circle. A disabled boy we assisted for years grows up to serve others in need—including myself, David Werner. The story of Carlos Garcia.

Back in 1986 when the PROJIMO village-based rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers was in its fledgling years, the team learned about a youngster in a neighboring village who couldn’t walk. Next day after a 2-hour drive we arrived at a small hut at the edge of a cornfield. The boy’s mother, Doña Lola, welcomed us in. On a homemade cot lay a thin boy about 7 years old, who looked at us with large, questioning eyes. He halfway smiled at us. His mother introduced him as Carlos Garcia Sarabia—and helped him sit up. This wasn’t easy for him. The joints of his arms and legs were swollen and any movement of them was clearly painful. After wincing a moment, Carlos greeted us hesitantly.

Doña Lola told us about the child’s affliction. He’d had a normal birth. His early childhood had for the most part been happy and playful. From the time he could walk, he loved to explore the cornfield with his father. Then one day, when he was two, as he was playfully running and jumping from one row of corn to the next, he fell down and cried out in pain. The following day one knee was swollen and discolored, and hurt when he moved it. In a few days the swelling went down and the pain went away. But this was the first of a series of similar events—often for no apparent reason, when different joints, usually a knee, elbow, shoulder, or wrist—would inexplicably swell up painfully.

By age 5 Carlos had reached a point where many of his joints frequently swelled up, and sometimes hurt so badly when he moved them that he would spend his time just sitting or in bed. Then it reached a point where he couldn’t even sit up without help—much less walk.

One day when one of Carlos’s knees had swelled more than usual, with great pain, his parents scraped together what little money they had and took him took him to a clinic in the coastal city of Mazatlán. There he was diagnosed as having an uncommon bleeding disorder called hemophilia, where the blood doesn’t clot normally. This causes profuse bleeding even of small wounds, as well as spontaneous internal hemorrhaging into joints. Without timely, ongoing treatment this can lead to chronic debilitating joint pain (hemarthrosis).

In the government clinic, to control his current bleed the doctor gave Carlos an IV injection of “clotting factor 8” and sent him home with instructions to come back every time he had another bleed.

“But the shots weren’t any help at all!” grumbled Carlos.

“And how can we afford to take him to the city for treatment every time he gets a bleed?” questioned his mother.

“What to do?” That was the big question … which attempts to answer have led us to more than 30 years of problem-solving ventures.

One of our first actions—since Carlos’s first injection of clotting factor didn’t seem to work—was to get his blood analyzed again at a reliable clinical lab in Mazatlán. It turned out that Carlos had a rarer type of bleeding disorder, Hemophilia B, not the far more common Hemophilia A. The doctor who’d misdiagnosed him as having hemophilia A had wrongly prescribed clotting factor 8, which for Carlos was useless.

So, our next challenge was to get a supply of clotting factor 9. The big problem was cost. Back in 1993 a single dose of factor—whether A or B—was around US$300. Today it can cost up to US$3,000 a dose, which puts it out of reach of most persons with hemophilia, worldwide. Time and again in my travels, I’ve seen children crippled by untreated hemophilia, unable to walk or even stand, begging in the streets, condemned to painful lives and early deaths, for lack of treatment … while the avaricious pharmaceutical corporations that produce the lifesaving factor rake in unconscionable profits.

Analysis showed that Carlos has the most severe type of hemophilia, with a clotting capacity less than 1% of normal. To prevent serious bleeds he should administer a dose of factor 9 every week. But the cost for this is prohibitive, for Carlos and for anyone without health insurance or universal coverage. And even in countries with universal coverage—especially in majority-world countries—it is a huge drain on the health budget.

For Carlos there was no way to come up with so much money. And government health services that supposedly provide universal coverage, consistently say they’ve run out of the medicine and to purchase it in a pharmacy. So we set about seeking donations of clotting factor 9.

Back in California, we contacted drug companies, pharmacists, and friendly hematologists, exhorting them to donate factor. We managed to get a small supply. But it was a constant struggle and we never got much.

But then we struck gold! Through the American Hemophilia Association, we were able to contact one of its members, Billy Jacobs (a pseudonym), who, like Carlos, had hemophilia B. And Billy came to our rescue. For years he’d been issued a supply of factor 9, cost-free through Medicare. Ironically, Billy had a hard time economically because, to get factor through Medicare, he could not be officially unemployed. So Billy lived on welfare and devoted his life to helping others. And he enjoyed doing so.

To make a long story short, Billy literally saved Carlos’s life. For some reason, the amount of factor 9 Billy was given by Medicare was double what he needed. So for the next 20 years, Billy faithfully provided Carlos with all the clotting factor he needed—enough to minimize his bleeds and keep him relatively healthy.

Another challenge was getting the clotting factor into Mexico and then down to Carlos in Mazatlán. But by hook and by crook, we somehow managed to spirit the factor through the Mexican border and into Carlos’s hands.

Carlos quickly learned how to give himself the IV infusions. Over the years, there have been many stumbling blocks to cope with. But overall we managed to obtain sufficient factor to keep his bleeds to a minimum and for him to pursue his life and his dreams.

Although, with a reliable supply of clotting factor, Carlos’s hemophilia was now largely under control, he still needed to cope with damage already done. When we’d first met, he was severely disabled. Because every movement was painful to where he’d been unable to sit up by himself, his muscles had grown frail. His knees became contracted in a bent position, so that even when free of pain he couldn’t have stood upright, much less walk. So we embarked on a long endeavor of rehabilitation. This involved numerous visits to PROJIMO, our village rehab program, which was then in the village of Ajoya. Carlos usually came with his mother. They stayed in the home of an amiable family who also had a disabled youth, who gladly helped Carlos with his rehab.

At PROJIMO, now that Carlos had less pain thanks to the clotting factor, the team began to help him become more functional. They involved him in playful activities to improve his strength. To straighten his knees they made him long leg plastic braces that could be gradually extended.

And once his knees were straighter, they put a long support made of cloth suspended between rebar projecting forward from his wheelchair seat. This helped keep his legs extended and gradually straightened them more. When at last he could stand upright, they helped him to walk between parallel bars. Then with crutches. And finally, all by himself. Village children invited him to play ping-pong and tether ball in order to improve his strength and coordination and have fun doing so. Carlos—and all of us—were excited by his progress.

Carlos’s biggest dream at that time, however, was to ride a bicycle. A young man in the village, who no longer used his bike, donated his to Carlos. And the thrilled boy gradually learned to ride it.

All in all, Carlos’s transformation was amazing. In a matter of months, he’d metamorphosed from a suffering disabled child to an eager, active little boy.

In terms of education, fortunately, from age 6 onwards Carlos’s family had made every effort to have him go to school. Since there was no school in their tiny village of Agua Fría, every weekday his mother would carry him on her back three miles to the nearest school, in Coyotitán, then carry him back home the afternoon. After the lad became more able-bodied thanks to clotting factor and rehab, the family decided to move to Coyotitán—primarily to be nearer the school. (They figured that, given his physical challenges, he should be prepared to earn his living with his mind rather than body.) Carlos was obviously bright and did well in his studies.

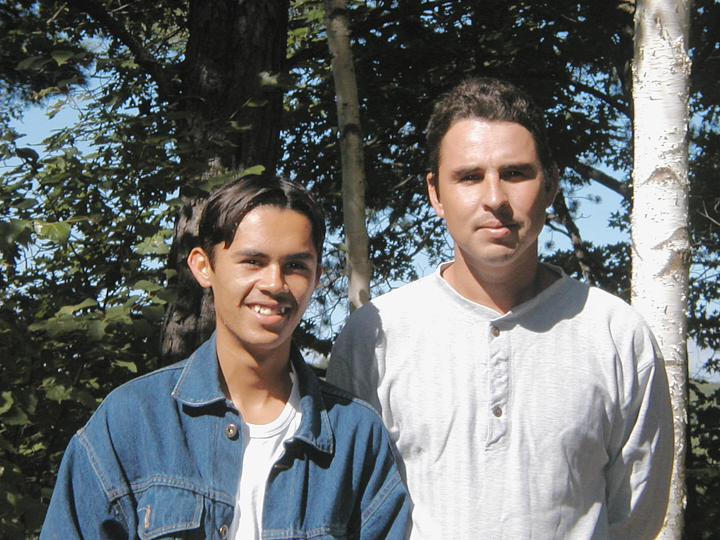

During all this venture I became a close friend of Carlos and his family. As he approached his teens I took him with another pair of other boys to my summer cottage Silver Lake. There he learned to swim, paddle a canoe, hike in the mountains, and he learned about mushrooms. He even earned a bit of money doing odd jobs for neighbors. Over the years, Carlos continued to visit me at my summer home in New Hampshire … and he has been a great help to me as I grow older (see below).

Perhaps because of all his early encounters with medical care, Carlos set his heart on becoming a nurse. On finishing school, with help from our organization and friends, he went through nursing school with flying colors.

Getting employment as a nurse, however, was another matter. Among other duties, in hospitals nurses have to do heavy lifting and other stressful tasks, which for Carlos with his damaged joints wasn’t feasible.

Yet finally Carlos lucked out. He got a job with a budding hospice program—the first in the city of Mazatlán. He threw himself into the work with dedication. Having suffered so severely himself from ill health, his heart went out to ailing folks approaching death. With many of those he cared for he became good friends. He enjoyed assisting them, even with their most embarrassing problems. What was most stressful for him was when they died, as the friendships and trust often had become so close. Though his pay was low he loved his work. Often, he stayed overtime, or gladly made off-hour visits if they called him for extra assistance, or simply companionship.

Carlos worked with Hospice for eight years, until the Covid pandemic struck and in 2020 home visits became a no-no. Life became more stressful for Carlos, since he was now married (and separated) and had three children to support.

At last Carlos found work caring for elderly North Americans who had moved to Mexico, where shelter and care are less expensive. Here, Carlos had an advantage over other nurses because he’d learned some English on his visits to the United States. The work, which involved 11-hour night shifts, was taxing. But he formed very warm relationships with those he cared for, and found his work fulfilling. The most troubling part was when the persons he’d been assisting died, it wasn’t easy to find new employment. And Carlos, who never managed to accrue much savings, loved his children and was committed to providing responsible child support.

During the decades that have passed since we first met, Carlos and I have remained close friends and kept in touch. A number of years ago, my beloved friend Trude and I had helped him to get a small car. This was needed because those he assisted often lived far away. Taxis were too expensive and travel by bus, given his hemoarthritic condition, was perilous. (The overcrowded buses often just slow down to pick up passengers, who must run and jump aboard, wriggling their way in through the crowd.)

With passing years, I’ve been growing old. And with my own disability—called Charcot Marie Tooth (CMT), an inherited progressive muscular atrophy that started in childhood—I’ve reached a point where I mostly use a wheelchair. For exercise I trudge around awkwardly with a walker, and I have many personal problems with which I need help. Nevertheless, I continue to visit Mexico and play a role in the ongoing community programs I’ve worked with for decades. Currently I’m most involved with Habilítate Mazatlán, a service project started by disabled former drug users, who design and construct custom-made special seating for children with unusually challenging needs (see our Newsletter 82).

Though I remain closely involved with these grassroots initiatives, for my increasingly challenging daily needs (bathing, toileting, putting on my full-leg braces, etc.) I now require an increasing amount of personal care. When in Mexico I find plenty of willing helpers. And in the USA, until recently, I had friendly neighbors from Tonga who very capably assisted me—until they moved back to the South Pacific.

This is where Carlos—now 39 years old—has come to my rescue and has cheerfully and capably stepped in to help. He managed to get a long-term visa to the USA (not so easy now that Trump rules the roost) and flew north to become my personal care attendant. He is highly skilled, deeply caring, refreshingly cheerful … and is totally at ease in helping me manage, even with my most embarrassing personal and quixotic needs. I feel incredibly fortunate to have such a close longtime friend to be helping me out so capably … a fellow traveler who not only cares for me but about me. Life goes full circle.

New challenges for the programs in Mexico—Updates

This December (2025) after I finish drafting this newsletter, Carlos will accompany me from my abode in California back to his home turf in Sinaloa, to spend time with family and friends. (While in Mexico, other friends will kindly see to my needs.) And I will keep busy. Already the Habilítate team has lined up a group of disabled children with especially challenging needs, for whom they request my input and advice. I’ll also be collaborating with the other programs in Mexico.

These have been difficult times for the community programs we have a long history with in Mexico.

The PRÓJIMO programs

(“PRÓJIMO” stands for “Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth in Western Mexico)”

PROJIMO Coyotitán

In the PROJIMO Coyotitán initiative the pace of their rehab services unfortunately has slowed considerably. In part this is due to the upsurge of cartel violence in the region (see above). And in part it’s due to the untimely deaths over the years of some of the program’s key players—namely: Marcelo Acevedo, master limb and brace maker, who died from cancer; Mari Picos, program coordinator, who died from pressure-sore related sepsis; Inez Leon (el Camaron), wheelchair builder and therapist, who died from Covid; and Jaime Alcaraz, welder and master wheelchair builder, who last year succumbed to complications of tirisia (chronic sadness) after the death of his girlfriend.

Fortunately, however, the program has been training several new rehab workers from among the disabled people who come to PRÓJIMO for rehabilitation and assistive devices—training in the respective skills of brace making, prosthetics, wheelchair building and physical/occupational therapy. Though these newcomers do not yet have all the skills and experience of their predecessors, they are doing quite a reasonable job and are improving as they gain more experience.

One noteworthy feature of the PROJIMO programs is that they are run and staffed principally by disabled persons themselves, an empowering feature that has been noted and adapted in other parts of Mexico, Latin America, and the world.

In some cases, disabled craftspersons from PRÓJIMO have gone back to their hometowns or countries and set up their own workshops.

And sometimes the benefits go full circle. An example is Nemías, a young amputee from Guatemala, who traveled all the way to PROJIMO to get a prosthetic leg. While having his prothesis made, and after, he received personal training in limb-making from Jon Batzdorff, a visiting master prosthetist from California, who heads an international training program called Prosthetica.

Then he went back to his hometown in Guatemala where he set up a prosthetic shop, and soon gained a reputation for his high quality and affordable work. We kept in touch. Years passed. Then, this August at PRÓJIMO, an amputee campesino arrived in need of a complicated limb. But sadly PRÓJIMO had lost its best limb maker and was therefore unable to meet the need, since nobody else had the required skill. But then, astoundingly, a well-to-do local friend of the program who had admired Nemías’s craftsmanship, came to the rescue. He paid for Nemías’s flight from Guatemala back to Mexico, where he skillfully made the needed prosthetic.

This spirit of caring and sharing has long been a hallmark of these unconventional programs, at their best.

PRÓJIMO Duranguito

The PRÓJIMO Duranguito workshop, which specializes in making individually designed wheelchairs for children with challenging needs, has had its ups and downs. The team has been working on the design of a hand-powered battery-assisted tricycle, intended to help spinal cord injured persons get to work through urban traffic. The goal is to make the trikes cheap enough for users to afford. But the high quality model the team came up with proved too expensive, now that cheaper but inferior, less durable models are being imported from China. So the program is now back to square one.

One of the biggest problems with PRÓJIMO Duranguito at present is aging. Unlike PRÓJIMO Coyotitán, Duranguito has not managed to recruit new, younger workers. Some former workers have left. And Raymundo, the program coordinator and chief wheelchair builder, who is paraplegic and now in his 60s, has multiple health problems that slow down his work. Also, for several reasons, the demand for their highly functional children’s wheelchairs has dropped—again partly because of the import of showy but unreliable chairs from China.

To accommodate more children in need, Duranguito is now planning to work more closely with Habilítate Mazatlán, which makes individualized seating out of cardboard for children who need them. As these children grow, some may need to graduate to a personally adapted wheelchair … which Duranguito can well provide.

PRÓJIMO Duranguito is exploring new options… but perhaps what it needs most is a few gung-ho younger workers.

Habilítate Mazatlán

Habilítate Mazatlán (Enable Yourself Mazatlán) is the service program in Mazatlán started by and for disabled recovering drug-users. The team designs and constructs individualized special seating, mostly out of laminated cardboard, for children with severe spasticity and other positional challenges that make normal sitting just impossible or further incapacitating. Designing this seating is complex, insofar as each child has unique features that require careful assessment in order to design a seat that helps break their spastic pattern or otherwise allows them to sit without twisting or falling off their chair. In the past, fortunately, I received some training from visiting specialists in evaluation of such children and design of these corrective seats. It’s a tricky skill that requires continuous learning. There’s always a place for learning more. So for children with more challenging needs, the team often asks me to help them figure out functional solutions.

In terms of program sustainability, for a time the number of children helped by Habilítate had declined, as result of the Covid pandemic coupled with the upsurge of violence, which triggered people’s fear to leave home. But now that Habilítate’s unique craft is more widely recognized, several of Mazatlán’s rehabilitation centers for disabled children are increasingly referring youngsters with challenging needs for custom seating and other assistive devices to Habilítate—increasing the number of children attended.

So disabled craftpersons formerly scorned as druggies are now applauded for their outstanding contribution. This appreciation helps keep them off drugs.

And so life and its wonders proceed.

Pre-announcement of a new art book

This last year, my close friend and co-director of HealthWrights, Jason Weston, and I have been working on an art book depicting my paintings, drawings and sketches over the last 70 years. Many of the pictures are in full color. The volume also includes the stories behind those illustrations that portray more telling and transformative events in my rather atypical life.

We hope to have the book in print within the coming months. We’ll send out an announcement at that time. So keep an eye out—and we hope you enjoy it.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |