Women Unite to Overcome Drunkenness

Word that she had been shot reached the village of Ajoya only a few minutes ahead of the stretcher bearers. People said that she was dying, shot in the back by her husband.

A few minutes later, a crowd of men, women, and children—shouting and wailing—streamed into the old adobe clinic. Sweating stretcher bearers carried Laura into the patio and lowered the homemade stretcher onto a cot.

An old woman, supported by others, cried out, “He killed her! He killed my daughter!”

The wound, however, was not serious. The bullet had entered Laura’s lower back, near the spine, had angled through the buttock and stopped just under the skin.

The physical problem was easily treated: a small cut to remove the bullet, cleaning of the wounds, pain-killers and antibiotics, and bed rest for a couple of weeks.

The social problem was more difficult to resolve. A manhunt started at once for Laura’s husband, Enrique, led by the young woman’s father and brother.

“You irresponsible drunkard!” shouted Laura. “My mother warned me…”

The full story I learned from the boy Martín. Martín Reyes was later to become a village health worker and eventually the coordinator of the villager-run health program based in Ajoya. But at the time of this shooting (1966), Martín was only a boy—fourteen years old.

The day of the shooting, Martín had been visiting at the small hut of his Uncle Enrique in the village of Arroyo Grande, two hours by foot trail from Ajoya. Enrique and Laura had been together for about a year and a half, and had an eight-month-old baby. They were very poor. For days they had been living on “puras tortillas.” That morning, Enrique had decided to go to the neighboring village of El Naranjo to see if he could borrow a chicken from his father-in-law so that the family would be able to eat well for a couple of days. But when Enrique arrived at the home of Laura’s father, he found him drunk, staggering through the village with a group of other men—all following a couple of paid musicians. Enrique was invited to join in.

Several hours later, Enrique arrived back at his but in Arroyo Grande, drunk and empty handed. Laura, who had been worried about the long delay, began to scold him. Enrique already felt guilty and could not bear the scolding. He ordered her to shut up. But Laura was furious. This was not the first time her husband had left to bring back food and had returned empty handed and drunk.

“I said shut up!” said Enrique.

“You irresponsible drunkard!” shouted Laura. “My mother warned me…”

“When I say shut up, I mean shut up!” barked Enrique. He took a leather mule blinder from a peg on the pole wall and advanced toward Laura with his arm raised. The boy Martín huddled in a corner, eyes wide with fear.

Laura turned and ran out the door, toward the arroyo. Enrique grabbed an old hunting rifle and pointed it after her. “Stop, or I’ll shoot!” he cried. Laura stopped and began to turn, but at that moment the rifle went off. Laura fell to the ground. Enrique dropped the gun, ran to her, and took her in his arms, weeping hysterically. “I didn’t mean it! I didn’t pull the trigger! The gun went off…” he cried. Martín crept out of the hut and ran to notify his family in the neighboring village.

In the manhunt that followed, Enrique was not found. While Laura was recovering in Ajoya, their baby had been taken by her parents’ family in El Naranjo. One night Enrique sneaked into his father-in-law’s house and “kidnapped” the baby. The manhunt was renewed with greater fury. But Enrique was never caught, and eventually things quieted down.

Today, sixteen years later, he and Laura are still living together. They have many children, but a difficult life. Enrique still drinks—but less so now that he is somewhat older and wiser.

Drinking in the Sierra Madre

The relationship between drinking and health in the Sierra Madre—as in so many parts of the world, is disturbingly clear. In Mexico, cirrhosis of the liver and homicide—both closely linked to excessive drinking—are among the top five causes of death in middle-aged males. But the indirect effects of drinking on the health of men, women, and children are even more severe. Drinking is

rarely done in moderation. (men drink with their fellows as a demonstration of brotherly love and bravado—but also as an escape from the hardships and injustices of daily life. Once drinking starts, it is difficult for a friend to refuse to join in. And to stop drinking before the money runs out or one becomes ill (or a fight begins) is considered rude—or unmanly. Poor campesinos (farmworkers) will often spend everything they have, and even sell their corn harvest before it is picked, once they start drinking. For wives and children, the resultant suffering is immeasurable, not only because of abuse, beatings, and shootings, but because of malnutrition. Poverty, poor nutrition, and drinking are linked in a vicious circle.

The problem of drinking and violence related to drinking has been especially bad in Ajoya, because the town serves as a kind of trading post for the network of small villages linked by mule trail throughout the sierra. Young men from the mountain villages periodically come down to Ajoya on mules or burros to purchase basic foods and supplies to take back to their families. For them, although Ajoya is a village of only 850 persons, it is the “big city.” When alcohol is available and men are drinking, too often the campesinos from the mountains are tempted to join in. They use up their money and return home with a hangover or aggravated stomach ulcer rather than food for the family. Or more tragically, they get in a fight and return wounded—or not at all.

Ajoya used to have two public bars where men would gather and drink, but there was so much violence and killing in them that the bars were closed down some twenty years ago and have never been reopened. Some drinking, of course, still occurs. Several families have “aguajes” (water holes) where they sell illegal liquor.These are occasionally raided by the state police, federal soldiers, and the local “síndico” (police chief). However, the síndico and his local policemen function more as accomplices than as controllers. Periodically they make the rounds of the aguajes to collect their cut of the profits.

Campesino Theater

Over the years, the central health team in Ajoya has taken a number of actions to try to deal with the problem of drinking. One approach has been through “campesino theater.” At the end of each training course for village health promoters, the whole village takes part in a “health festival.” The health workers help organize the towns-people and school children to put on musical performances, dances, and short skits that deal with important health problems. Recognizing that drinking is one of the most difficult problems affecting health, three years ago the health workers decided to put on a skit about this problem and the possibilities for overcoming it. They thought that the most appropriate persons to put on this skit would be those most concerned about the problem— namely the women. The health workers went from house to house, talking to mothers and wives about whether they would like to participate. The women’s response was overwhelming. Some of them actually began to weep as they told of the drinking problems in their own families. On learning the theme of the proposed skit, some of the oldest and most dignified women in town, who had never dreamed of acting on a public stage, said they would take part because the problem of drinking was so important.

The play was based on an organized action taken by women in Monterrey, Nuevo León. There, in the large squatter settlement of Tierra y Libertad, women had joined together to close down the public bars and put up an “overnight jail” for abusive drunks.

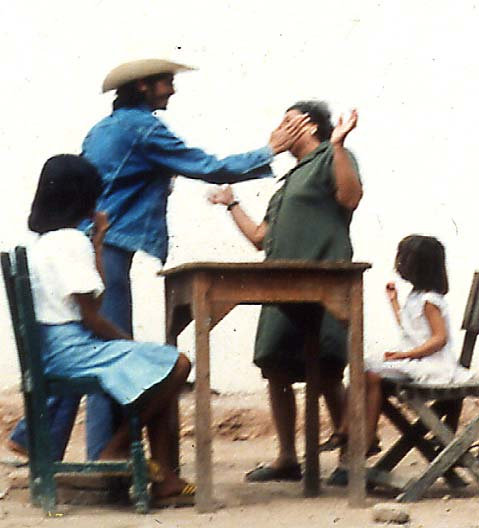

Adapting these events to the situation in Ajoya, the play was put on completely by women and children. Some of the women dressed up in pants, pistols, and mustaches to play the roles of men.

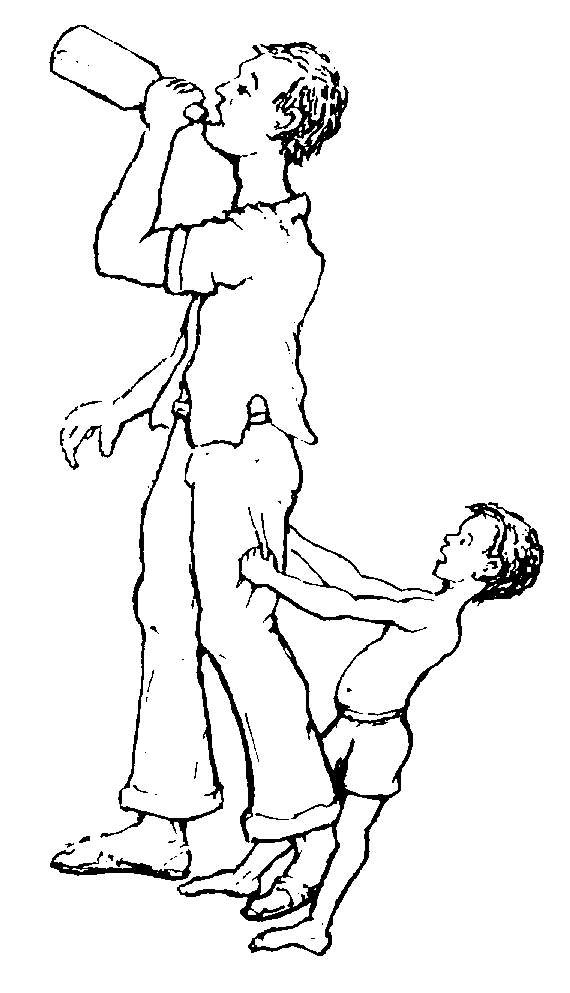

The play opened with two children crying out to their mother, Tristina, “Mamá, I am hungry,” as the family waited for the father to come home from the village store. Finally, the father, Al Cole, came with a bottle of mezcal in one hand instead of food for the family. The scene moved from one household to another, showing similar problems. Drunk men hit their wives and fired “joy shots” through the roof with their pistols. Women and children abandoned their homes to take refuge with neighbors. At last, many women gathered together in Tristina’s home, weeping over their plight.

|

|

|

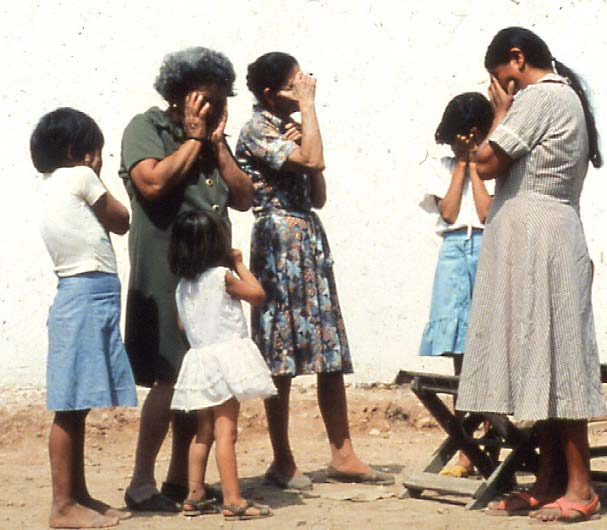

In despair, one woman cried out, “What can a woman alone do in this world of men?” Another woman remarked, “But right now we are not alone. We are together! There must be something we can do.” So the women began to plan. Soon they were organizing all the women in the village, plus any men who would cooperate with them. They demanded that the síndico, if he wanted to keep his job, close down the illegal aguajes. They also pressed for the building of an overnight jail for drunks. The síndico grudgingly gave in to the women’s demands. This led to far less drinking in the village. In the last scene, the women and children raised their fists and cried out, “Las mujeres unidas jamás serán vencidas!” (The women united will never be defeated!) †

† A few of these skits have been included in Helping Health Workers Learn.

The play caused a lot of discussion in the village, but for the time being it seemed to produce few direct changes. One woman closed down her aguaje, but others continued to function.

Two years later, however (in the fall of 1980), the síndico and municipal police suddenly began to clamp down strictly on the illegal aguajes, confiscating the liquor and heavily fining the sellers. The net effect was a noticeable reduction in drinking in the area. But some of the villagers were skeptical. The governor of Sinaloa had recently begun a statewide campaign to open licensed neighborhood bars, in order to gain revenue through liquor taxes. The campaign had even reached the point where, in one urban neighborhood, a kindergarten had been closed down in order to make way for a saloon. The villagers in Ajoya suspected that the authorities were closing down the aguajes so as to destroy competition, before they opened their own public bar for personal profit.

The Struggle Against The Opening of a Saloon in Ajoya

This proved to be the case. Within a month the municipal president from San Ignacio, together with the “secretario” (the second in command, whose. brother was appointed síndico of Ajoya), began the construction of a saloon in Ajoya. No village meeting was held to discuss whether the community was in favor of a bar or not. The building of a bar was a private business venture for the municipal president’s personal profit.

Many people began to grumble and complain among themselves—particularly older persons who remembered the violence and bloodshed that had led to the bars being closed twenty years before. But everyone believed that nothing could be done to stop the bar from opening. The owners were wealthy and held strong government positions.

However, the health workers began to meet and talk about things with the local women. Remembering the play that they had put on two years before, some of the women were determined to organize and try to prevent the opening of the new bar. But at first, most thought there was no way they could stand up against the power and influence of the municipal president.

The biggest resistance came from the men folk, who were afraid of what might happen to them if they, or even their wives, openly opposed the saloon. Some husbands flatly ordered their wives not to become involved. Nevertheless, more and more women began to join the group and to speak out. Together with the health workers, they began circulating a petition both in Ajoya and in surrounding villages. Within a few weeks, virtually all the women and nearly eighty percent of the men had signed the petition. Some men who were the heaviest drinkers were the first to sign up; they feared for the well-being of their families if the public bar were opened.

A committee of six women and two male health workers took the petition to the Chief of Alcohol Licensing in the state capital. The chief promised to review the matter, but offered their little hope. He explained that, according to present government policy, a liquor license was granted to almost anyone who had the money to pay for it.

The last of the six to be arrested was Miguel Angel Alvarez, who has played a leading role in organizing the protest against the bar

Soon, trouble began. A few days after the group’s trip to the state capital, Martín, then coordinator of the village health team, was dragged from his house in the middle of the night by a group of soldiers. They accused him of having provided emergency care for a man the soldiers had wounded in the mountains. Although the health workers do, of course, provide emergency care to whomever needs it, in this case Martín could prove that at the time he had been far across the mountains in Durango. The soldiers released him. But the villagers suspect that Martín’s arrest was harassment for the health team’s opposition to the public bar.

The harassment continued. By June, six members of the central health team had been arrested. But there were no legal charges that could hold, and each was released after spending no more than a few days in jail.

The last of the six to be arrested was Miguel Angel Alvarez, who has played a leading role in organizing the protest against the bar. He was jailed in San Ignacio with no charge other than that of being an “agitator.”

A group of women went to San Ignacio to demand Miguel’s release. With the women gathered outside the jail, an authority entered and told Miguel he would be released at once if he paid a 1000 peso fine.

“Before I pay any money, I should be charged in writing with a crime,” said Miguel. “Are there laws against communities taking peaceful action to protect the health of their citizens?”

“Forget the thousand peso fine, then. Just leave!” said the authority.

“No,” said Miguel. “I won’t leave the jail until I have a written statement that I have been released without charges.” The women outside were clamoring. The jail keeper wrote him a hurried note of release, and Miguel was set free.

From this point on, the contest between the people and the municipal authorities became more direct—and better publicized. However, the independent newspapers, as well as social leaders in the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, have come to the villagers’ defense. First, El Debate ran an editorial accusing the municipal president of using repressive tactics and abuse of government power to promote his personal business interests at the people’s expense. In response, the president wrote to the governor accusing the Ajoya health team of dangerous malpractice, and demanding that the villager run program be closed down at once. But the Sol de Sinaloa—largest newspaper in the state—ran a full-page editorial entitled, “They Want to Close Down the Ajoya Clinic.” The editors reminded the governor that when he had been Minister of Agrarian Reform, his ministry had had so much confidence in the Ajoya health team that it had employed the team to train the ministry’s first batch of community health workers.

As a result of these articles, the ensuing public outcry, and pressures put on the governor by friends in the state capital, the governor was forced to reprimand the Municipal President for his misuse of authority.

The Immediate Results of the Villager’s Efforts

The villager-run clinic continues to function, with stronger support from the poor than before. What is more, the permit to open the bar in Ajoya has been officially refused.

The municipal president did not give up easily. At first, he kept trying to pressure state authorities for a liquor license. But an incident on the Día de San Gerónimo—as if fated by an angry god—cast a final, harsh verdict to keep the saloon closed. Every year on September 29 (Day of San Geronimo, patron saint of Ajoya), a huge festival is held to which people come from miles around. For this festive day only, government permits are sold to allow beer sellers to set up temporary saloons by the plaza. This year for the fiesta, the ex-municipal president (who, together with the current municipal president, had been trying to open a year-round saloon in Ajoya) set up a one-day saloon. The results were fatal. On the night of the fiesta, a teenager from a mountain village called El Molino was drinking with the crowd at the bar. Another young man, an enemy of the family, came up from behind and tapped him on the shoulder. As the boy turned around, the man shot him point-blank in the face. The killer then turned on his heels and walked calmly through the crowd, to where a narrow alley led between the houses to the river. In the shadows, he paused to light a cigarette before he disappeared. Neither the síndico nor the policemen pursued him.

People took the killing as an omen. “One day a year with a saloon, and look what happens!” they said. “The women and the health workers did right. Imagine what it would be like with a saloon open every night of the year!”

Every year on September 29 (Day of San Geronimo, patron saint of Ajoya), a huge festival is held to which people come from miles around

One result of the people’s successful opposition to the bar has been a reduction of excessive drinking. This may be related more to an awakening consciousness than to availability of liquor. Some of the aguajes still function. But men no longer get drunk so often, or make such a public display of it as before. There is a different climate in the village—a kind of healthy pride in maintaining sober control.

When I (David Werner) visited Ajoya this last Christmas, I was delighted to see how peaceful the village was. In the past, Christmas Eve has often been the bloodiest night of the year, due to drunkenness and resulting fights. One Christmas night several years ago, I had to patch up a total of 18 bullet holes in 5 people. But this year there was no fighting, nor even drunken carousing in the streets. Those who drank, did so quietly in their homes.

The most dramatic reduction in drinking has been among the health workers themselves. Some of the team members have had serious drinking problems—a contradiction much discussed because of the poor example this sets. But now that the health team has played a key role in preventing the opening of the bar, the health workers feel it is extra important to set a good example. And for the most part, they do so.

Since the murder on the day of the fiesta, the authorities have not tried to open the Ajoya bar again. Village women are discussing renting the empty saloon to set up a sewing cooperative as a source of income. (They are requesting funds and materials to help start this sewing co-op, in case any of you readers want to help out.)

Long-Ranged Results

The long-range results of organized public opposition to the bar still have to be evaluated. But they promise to be far reaching. The villagers’ visible success in taking a stand for public health against the abuses of the powers-that-be has given them new confidence, dignity, and courage. Throughout the mountain area, people proudly say, “We signed the petition, too, you know. And we won!”

The successful opposition to the bar seems to have been a turning point in the process of community awakening toward which the health team has been working for years In the past, the health team has gained participation of the poor in indirectly opposing their exploitation by those in power. For example, they formed a cooperative corn bank which lends maize at fair rates, thus freeing the poor from having to borrow at usurious interest rates from the rich. And a “fencing loan project” permits groups of poor farmers to jointly fence marginal land and sell grazing rights, rather than having to perpetually forfeit grazing rights to the rich in lieu of interest on loans for fencing.

Until recently, however, few poor persons dared to stand up or speak out for their interests in public meetings. Since the bar incident and the success of the women, however, the “voiceless poor” have found their tongue. They are beginning to organize to defend their long-violated constitutional land rights.

For example, the village land council, with a puppet director, has for decades been completely controlled by the rich. But this August, the poor farmers organized and succeeded in electing as the village council director, Pablo Chávez, one of the leaders of the village health team. Pablo’s platform has been fair and legal distribution of the communal lands. Already the new village council has succeeded in obliging the rich to pay grazing rights to the poor who farm the land. And the villagers are working toward other equalizing action. They have been careful to remain within their constitutional rights, and so far, at least, have made headway without any violence on either side—which, for Latin America, is remarkable. †

† However in the newer sister program in Huachimetas, Durango, with which Martín has been closely involved, a health worker and his brother were recently killed by the state police. The Huachimetas health team had been actively opposing theft by local authorities of the poor people’s timber-rights payments.

The impact of the village health team and the women in opposing the bar has reached far beyond Ajoya—in part because of the publicity given it by the independent newspapers. In several parts of the state now, other communities—both urban and rural—have begun organizing in opposition to the government-promoted setting up of saloons in their neighborhoods. A social scientist from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa has told us that in several communities he has visited, women who are beginning to organize to defend their rights have told him, “If the women in Ajoya can do it, so can we!”

A New Book for Instructors of Health Workers—One that Links Health, Education and Social Action

Over the last several years, the village health team in Ajoya has become increasingly concerned with the social, economic, and political factors that affect the health of the poor. They have also come to realize that the people’s attitudes about themselves, their situation, and their possibilities are deeply affected by the kind of education they receive. What and how children (or village health workers) are taught has a lot to do with the way the poor end up looking at themselves and their world. Health is more dependent on politics and education than on medicineand vaccines.

Gradually, the Ajoya health team has been developing an approach to learning and teaching that helps everyone—instructors, health workers, villagers, and children—relate to each other as equals. They try to use methods that help people value their own experiences, analyze their situation, build on local traditions, and work together toward change.

Many of the teaching methods and aids that have been developed over the past several years in Ajoya, along with ideas from other community-based health programs in other parts of the world, form the basis for a new book by David Werner and Bill Bower. This book is called Helping Health Workers Learn. It has been prepared as a companion volume to Where There Is No Doctor (now translated into at least 17 languages and being used in over 100 developing countries as a training and work manual for community health workers). With this newsletter, we enclose an announcement of Helping Health Workers Learn and an order form.

More New Developments (Since the Last Newsletter—1979)

1. Educational Exchanges Aamong Community-Based Programs

The health team of Project Piaxtla has made more effort to share the innovative ideas it has developed over the years with other programs in other parts of the world.

In Mexico and Central America, there are dozens—indeed, hundreds—of community based, non-government health programs. In recent years, an increasing effort has been made to build communications between different programs, to share ideas, and to learn from each other. The Ajoya team has cooperated closely with the Regional Committee of Community Health Programs, until recently based in Guatemala, to promote such communications.

The third biannual “Encuentro Regional” or regional meeting of community health programs was held in Ajoya, Mexico in the spring of 1980. In addition, members of Project Piaxtla attended a regional meeting of Mexican health programs in Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo and have traveled throughout Mexico visiting other local programs.

Project Piaxtla has also held two “Intercambios Educativos,” or educational exchanges, two to three weeks long, in which village-level instructors come together to share ideas and to compare approaches and problems. These educational exchanges have been both a source of information for our new book, Helping Health Workers Learn, and occasion for field testing of preliminary drafts.

2. Visits by Piaxtla Leaders Outside Latin America

In many health programs around the world, increasing importance has been placed on the need for villagers and people working in their own communities to take responsibility and play a leading role in planning and decision making. But when it comes to conferences and policy-making on a regional or international level, usually only the professionals and experts attend. We feel there is a desperate need for village-level health and development leaders to be involved in more conferences and interchanges at the international level.

This has begun to happen in Latin America. Several times in the last three years, health workers and village-level instructors from Project Piaxtla have visited other programs in Latin America. Health workers from other programs have also visited Ajoya for training programs, apprenticeship in dental skills, and other activities.

The conference closed with an official decision to change its title from “Let the Village Hear” to “Let the Village Be Heard.”

Also, in 1980, Martín Reyes, coordinator of Project Piaxtla, had an opportunity to attend a conference in India entitled “Let the Village Hear.” As it turned out, he was one of only a few villagers present at the conference. Yet his impact was considerable. He stressed the need for more villagers to have a chance to exchange ideas rather than to be talked about. The conference closed with an official decision to change its title from “Let the Village Hear” to “Let the Village Be Heard.”

In the month of August, 1981, a unique interchange was arranged in which village health workers from Central America had an opportunity to visit the Philippines and exchange ideas with health workers there. Arrangements were made and funding raised by an Inter-Agency Committee of health programs in the Philippines.

Participants from Latin America were:

-

Martín Reyes and Roberto Fajardo, coordinators of Project Piaxtla,

-

Exequiel Gómez, village health worker and president of ASECSA, a Guatemalan association of community-based programs,

-

Julia Saldanas, leader in an outstanding all-women’s health promoter program in Honduras, plus

-

Bill Bower and David Werner from the Hesperian Foundation.

This interchange was of enormous value and stimulus to the participants both from the Americas and the Philippines. A great many insights were gained on both sides about health, politics, and the need for the poor of the world to work together for change. The idea for the women’s sewing cooperative mentioned earlier came from a visit to such a co-op in the Philippines.

We hope that more such interchanges between village-level workers of community based programs within countries and between countries will be possible in the future.

3. Prospects for a Unique Rehabilitation Program in Ajoya

For years, Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation have been bringing children with infantile paralysis and other disabilities to the Shriner’s Hospital for Crippled Children in San Francisco.

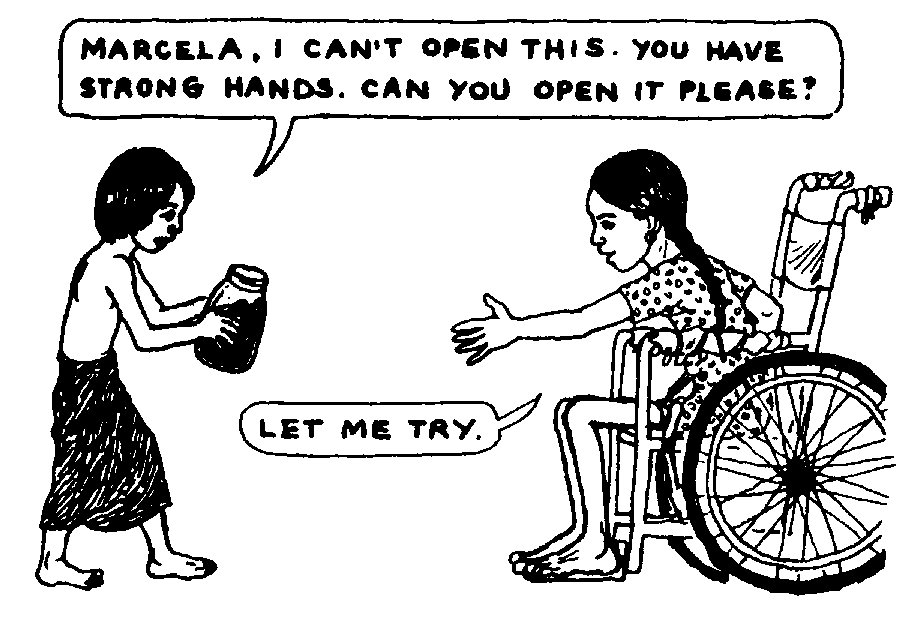

But the disabled children for whom hospital care can be arranged (or is appropriate) represent only the tip of an iceberg. The Ajoya team has begun to work with the families of handicapped children so that supportive care and basic therapy can be provided at low cost by parents, brothers, and sisters at home.

Now the Ajoya health team—several of whom are handicapped themselves—has determined to start a villager-based rehabilitation center. This will be run by disabled villagers to serve handicapped children and their families. The main focus will be education of the family and integration of the disabled child into family, school, and community. Already there is a lot of interest in the village. The son of the blacksmith—a young man with a leg crippled by polio—has offered to provide a large inside porch as an orthotics workshop, and to teach blacksmithing to other disabled participants. A village welder is eager to learn techniques of low-cost wheelchair making from a paraplegic craftsman in San Francisco, and to teach others. Contacts have already been made with self-help disabled groups in Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Thailand, exploring possibilities for exchanges for villagers to learn skills including physical and occupational therapy, brace and artificial limb making, appropriate technology in wheelchair construction, educational toys for the handicapped, homemade therapeutic aids, etc.

Already a set of color slides, taken in Ajoya, on simple home rehabilitation methods at the village level, is being used by UNICEF, Rehabilitation International, and other groups.

For those interested in a detailed prospectus of the proposed community-based rehabilitation program, to be called “Project PROJIMO,” please write the Hesperian Foundation. We are looking for donations of funds, tools, materials, and volunteer help (preferably by disabled persons able to teach rehabilitation-related skills.)

After Hurricane Norma: Help Needed to Revive the Cooperative Corn Bank

For five years now a cooperative corn bank, run by the health team in Ajoya, has been lending maize to poor campesinos at low interest rates. In the past, poor farmers had to borrow maize from rich landholders at planting time and then pay back 2 1/2 to 3 times what they had borrowed. This meant that every year, the poor would go deeper into debt. When they could no longer pay off their debts, the land holders would sometimes strip their homesteads of everything they had: chickens, pigs, the donkey, even furnishings. The high interest rates on corn loans has been one of the main factors contributing to the mass exodus of poor farm families to city slums.

The corn bank, which was started by villagers cooperatively farming a loaned parcel of land, has permitted many families to get out from under the oppressive yoke of high interest rates. Two years ago, so many small farmers had become self-sufficient in corn supply that, at the beginning of the planting season, the corn bank actually had a surplus.

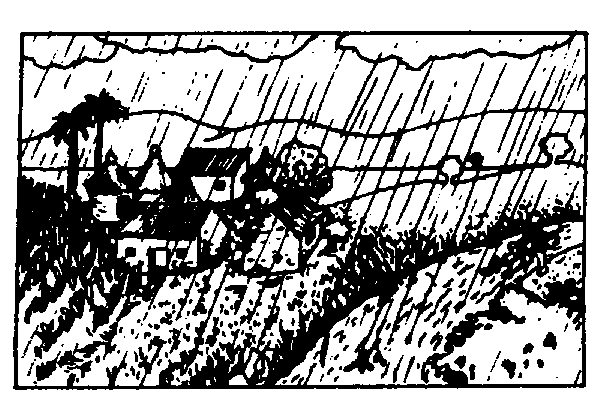

This last September, Hurricane Norma struck the Piaxtla area with great violence. Roofs were torn off, adobe homes collapsed, trees snapped like match sticks, and ripening cornfields were flattened. Families who had borrowed maize from the corn bank will not be able to pay their debts. Worse yet, the bank may have no maize to lend the stricken farmers for the next planting season.

Because of the hurricane disaster, Project Piaxtla is now asking for emergency relief assistance to help re-stock the cooperative corn bank.

Your assistance, large or small, will be appreciated. A proposal is available on request for individuals or groups who might consider substantial contributions.

The Hesperian Foundation’s Prospects for the Future

Like Project Piaxtla, the villager-run health program in Mexico, the Hesperian Foundation has continued to evolve. The foundation which began over a decade ago as a support group for Project Piaxtla now maintains communication with community-based health programs in many parts of the world. At present, the foundation staff consists of a team of six persons with varied talents—either volunteered or under-paid, plus a number of part-time volunteers. David Werner and Bill Bower spend a part of their time visiting community health programs as facilitators and troubleshooters.

Our main efforts over the last few years have been in the development of health materials: books, papers, educational slide series, and learning aids aimed at the village level. We have just completed the idea book for village level instructors, Helping Health Workers Learn (discussed earlier). Also, we have been collaborating with Murray Dickson (a Canadian with experience in primary health care in Papua New Guinea) in preparing a village dental care book to be entitled Where There Is No Dentist. With luck, this will be in print before the end of 1982. We are getting started on a small book on oral rehydration (Return of Liquid Lost), a topic of great importance in view of the fact that dehydration from diarrhea is the number one cause of death in children in the world today. We also hope to put together a simple book on methods of Home Therapy and Rehabilitation for Families of Disabled Village Children.

On the enclosed announcement sheet about Helping Health Workers Learn, you will find a list of other Hesperian Foundation publications. We would appreciate comments and suggestions from anyone reviewing the books and materials we have already produced. At present we would especially like people’s reactions to our new book Helping Health Workers Learn. Also, if anyone has any ideas or suggestions for our future publications, we would appreciate hearing from you—especially those of you who are village health workers or instructors of workers or are actively involved in the community with helping people meet their needs.

End Matter

Please note: Sections and other presentational elements have been added to this early Newsletter to update it for online use.

Note: This Newsletter has been written primarily for the friends of Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation who are already familiar with the history and activities of these groups. If, however, you would like more information about Project Piaxtla and the Hesperian Foundation, please do not hesitate to request it.

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |