Marcelo and Luis

Marcelo feels caught. Once again he doesn’t know what to do. He is sure that a joke is being flayed on him and he is confused. Lacking the tools for understanding, Marcelo resorts to his tried and true response. “Don’t look at me.” he demands. And, with a quick jerk of his head away from the insult, he trundles off, looking for more hospitable company.

Seeing Marcelo retreat from the brace shop, sad eyed Luis lets out his unmistakable cry. A throaty bellow and waving limbs draw Marcelo to his side. Intuitively, Marcelo deciphers the message that Luis needs company. Away from his family for the first time and having a hard time making himself understood, Luis, after three days, is somewhat desperate. Marcelo is gentle with Luis, but there are others who love to tease him. One of the favorite games they play with Luis is asking him if he misses his mother. Then his beautiful brown eyes look at you with heart-wrenching sadness as his head drops into the crook of his elbow. With tears running down his face and arm, Luis sobs quietly until he is comforted.

Marcelo doesn’t know how to play that kind of pine, but he does know how to push a wheelchair. He is strong, and enjoys pleasing his passenger. Luis loves going for rides, so the two of them head up-the narrow path leading to the main street of Ajoya. It is a hot day. The mangoes are almost ripe. The dust lifts easily and quietly coats everything. The younger kids, almost impervious to heat, are playing, while the men tilt back against shaded adobe walls, waiting patiently. There is a timeless calm hanging over Ajoya as the afternoon sun bakes motion to a stop.

The squeaking of dry bearings and a cloud of dust temporarily interrupt the magical stillness. Nearly indifferent eyes follow the pair as Marcelo pushes Luis’s wheelchair through the hot sun. Wheelchairs inhabited by all varieties of disabled bodies have become so commonplace in Ajoya that they no longer generate curiosity or fear in the villagers.

Luis answers Marcelo with his deep expressive eyes, as if to say, "Let's go on. I know you must be getting tired, but I'm so excited."

The overwhelming heat finally forces the two companions to seek relief. Marcelo’s round, soft body is shining with perspiration while Luis’s angular, contracted body sticks uncomfortably to the vinyl seat and back of his chair. “Shall we go to the river?” Marcelo asks hopefully. Luis eagerly agrees to the promise of adventure and escape from the oppressive heat.

With sweat streaming, the two companions make their way through the end of town and down the treacherous path towards the river. Boulders, erosion ruts, and deep sand turn the half mile into a monumental expedition. At times, Luis has to slide his spastic body out of his chair and drag himself over impassable obstacles while Marcelo handles the progress of the chair. In one spot, Marcelo has to carry Luis across a deep ravine, set him down on the far side, and then return for the chair.

The patient determination of the two companions builds a feeling of friendship that is both wonderful and foreign for them. Twice Marcelo asks Luis if he wants to abandon their mission. Both times Luis answers Marcelo with his deep expressive eyes, as if to say, “Let’s go on. I know it s a lot of work for you and you must be getting tired, but I’m so excited. I love you for being willing to take care of me like this.” Marcelo correctly interprets the response, and the two slowly labor on towards the river.

When they finally arrive, Marcelo, hot and dusty, splashes into the slow-moving, tired river. The small stream of water looks insignificant as it cuts its narrow path through the huge riverbed. Soon, when the rains come, this calm trickle will become a raging torrent, at times filling the entire riverbed with a powerful flow of boulders, branches, and silt-filled water carried down from the high valleys of the Sierra Madre.

Marcelo splashes his face with the tepid, green river water and looks upstream at the town he now thinks of as home. He can’t remember how he got to Ajoya, but he knows it is where he is happy -happier than he ever imagined possible. He thinks about the important jobs he has. He washes people who can’t wash themselves and dresses them in clean clothes so that they look nice. He fetches sodas for the clever men who make amazing things in the workshops. Sometimes they even give him jobs in the shop, and that makes him feel so proud.

People like him here. Sure, they tease him, but he’s used to that—and, besides, here they tease with a smile. And those around him have problems too. Many of them have bodies that don t work right. Some have shrivelled legs and walk with crutches, and some sit in wheelchairs all the time and can’t feel their legs. There are others like Luis, who can’t control their bodies and have to live with twitches and jerks that keep them from talking or moving the way they want to.

For his part, Marcelo has a good, strong body. He can help in a lot of ways, but his thinking doesn’t work right. He doesn’t understand many things, and he has a hard time remembering. But when something is clear, Marcelo is happy to do it. He loves to write. He fills pages of notebooks with sentences that have been written for him to copy. He can’t read and doesn’t know what he’s writing, but it doesn’t matter. He is doing useful work!

A loud splash brings Marcelo out of his thoughts. Luis has slid out of his chair and dragged himself into the river. Happily splashing away the heat and dust, he gives Marcelo a huge grin. Marcelo is a bit worried because Luis is wearing all his clothes and they are getting soaked. Luis smiles as if to say, “It’s fine. My clothes are hot too.” Marcelo laughs and plops down in the river next to Luis. Luis splashes uncontrollably and Marcelo imitates. The two friends are soaking wet and thoroughly enjoying the fruits of their difficult trek.

Across the river, on the bank overlooking the bathers, a wealthy landowner watches the scene. Sitting astride his horse, he contemplates the wheelchair. Watching the two friends, he realizes what a good thing it is that these children have a place to be where they can enjoy life and be valued for their ability to smile, laugh, play, learn, work, and be helpful in whatever way they can.

Moved by a sudden impulse, the horseman spurs his beast down towards the two boys just as Marcelo is lifting the joyous Luis back into his chair. Surprised and scared by the approaching rider, Marcelo almost drops Luis and becomes confused about whether to run, fight, or remain still. Fear fills Luis’s eyes as he senses Marcelo’s anxiety. With fewer options available, Luis sits and waits to see what will happen.

As they head back to Ajoya, with Luis groaning happily and Marcelo gleefully pushing the empty wheelchair, Chuy feels glad that he decided to help.

“Don’t be afraid, my friends. I will not harm you.” Marcelo and Luis slowly look up at the horseman. He smiles at them and swings down off his horse. He is a small man, much smaller than Marcelo, but he has the strength of someone accustomed to having power. “My name is Chuy. I was watching you two play in the water, and I thought you might like some help getting back to Ajoya. ’ Marcelo is uncertain. The friendly offer confuses him; he is torn between temptation and fear. Luis, on the other hand, is thrilled. His quick mind has already determined that he is about to go for a ride on a horse. The man senses Luis’s excitement and offers him a ride back home. Marcelo still can’t make up his mind. Decisions are a threat to him, especially when they involve responsibility. Fortunately, Chuy resolves Marcelo’s confusion by helping Luis lift himself onto the horse.

Loading a spastic child onto a horse is no easy task, especially when the child is nervous and excited. Marcelo quickly sees that his assistance is needed. Chuy is barely able to lift Luis, much less raise him onto the horse and pry his legs apart enough to straddle the horse’s back. After several exhausting attempts, Luis proudly sits astride the horse with his hands tied together around Chuy’s waist to keep him from falling off. When drool starts running freely down the man’s back, he momentarily questions his generosity. But as they head back to Ajoya, with Luís groaning happily and Marcelo gleefully pushing the empty wheelchair, Chuy feels glad that he decided to help.

Long shadows and cooler temperatures greet the trio as they enter the village. Thirsty, they buy and drink three sodas. At least half of Luis’s soda makes a sticky mess down his front, and onto the saddle and horse. This time Chuy doesn’t even flinch. He knows it can be cleaned up, and he doesn’t want to disrupt the mood.

A group of small children trail along behind the trio as they enter the PROJIMO yard. The workers in the metal shop stop their work to watch and yell out greetings. Other children playing in PROJIMO run over to the horse and riders. Marcelo proudly helps Luis down off the horse and returns the joyous child to his chair. Luis is overwhelmed with excitement as tears of happiness run down his cheeks. Chuy wheels his horse around, waves goodbye, and rides away content and a little embarrassed by Luis’s tears. It’s a moment he will never forget.

Marcelo, on the other hand, has already forgotten where they have been and why they returned the way they did. With waving arms and almost decipherable grunts, Luis explains what happened and why they were gone so long. Some of the more responsible people pretend to be upset with Marcelo for running off like that. Marcelo feels very bad and is still not quite sure he knows what he did. He does know that he feels happy and proud when Luis smiles at him.

Later that night, when Marcelo lifts Luis out of his chair onto his sleeping mat, Luis manages to get his arms wrapped around Marcelo’s back. When the time comes to let go, neither one of them does so. For a moment, the two friends hold each other quietly. When they do release their embrace, their eyes meet. Something they can’t explain has happened, and they know it is important. HW

Community-Based vs. Home-Based Rehabilitation

Readers of the previous story will note that Luis and Marcelo are both young persons who have left their own homes for a time to stay at a community rehabilitation center.

A fiery debate has been going on for some time among advocates of “community-based rehabilitation” CBR). Those who favor the World Health Organization (WHO) approach, which really amounts to “home-based” rehabilitation, argue against any sort of rehabilitation center for children outside of their homes. On these grounds, the home-based purists have often criticized PROJIMO as being “just another institution.” Other advocates of CBR have found that community centers run by disabled persons and/or their relatives can provide a very important back-up for rehabilitation activities in the home. They can offer a range of services, equipment, and opportunities that few families are able to provide. Far from being just another confining institution, a small “user-run” community center can provide a truly liberating experience.

Perhaps under ideal circumstances, the best place for disabled children is their own homes. There can be no doubt that family members need to learn as much as they can about helping disabled children (and adults) meet their needs and play a full, active role in their communities.

But real life is not always ideal. Mothers are often already overworked and simply don’t have the time to provide all the stimulation and special care a disabled child needs—even if they learn the necessary skills. Or the family may have become so locked into a pattern of overprotecting or neglecting the disabled person that, even with all the advice and support in the world, it has trouble shifting gears.

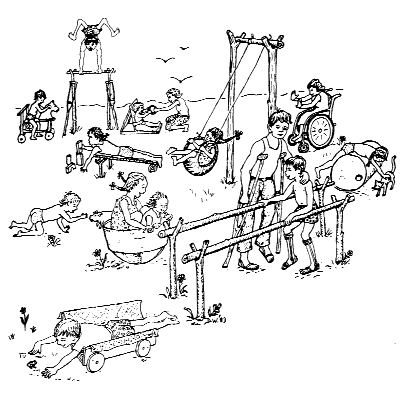

For children in such circumstances, a stay at a small community center can make a big difference. The team of disabled village workers at PROJIMO has found that for many young people a chance to spend a few days, weeks, or months away from home at the community center often gives them a whole new image of themselves and their possibilities for the future. Perhaps most important of all is the role model offered by the young disabled workers and leaders at PROJIMO: persons in wheelchairs or on wheeled gurneys do welding and carpentry, make wheelchairs and orthopaedic appliances, and have acquired skills beyond those of many able-bodied members of the community.

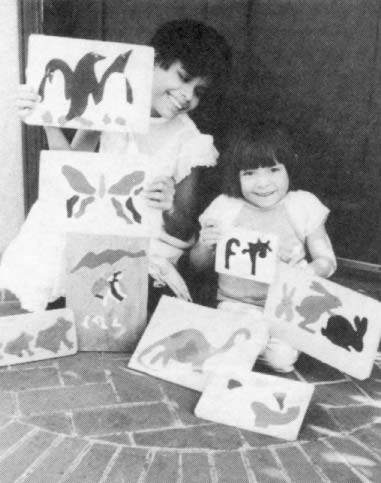

For example, when Marcelo, the mentally handicapped young man in the previous story, first came to PROJIMO, he was sullen and uncommunicative, and appeared to think of himself as worthless—an opinion his family clearly shared. Until another disabled child interested him in making wooden jigsaw puzzles (a skill he has still not mastered), Marcelo did not even want to stay at PROJIMO. But in time Marcelo’s experiences at PROJIMO led him to discover his strengths: a combination of tenderness and brute force. Above all, he realized that he could be useful and was needed. He became a very helpful “attendant” to many of the severely disabled persons such as Luis, transferring, bathing, and transporting them with an unquenchable, childlike enthusiasm. What is more, Marcelo has become an excellent role model for other mentally handicapped young people and their families, who can see what is possible when such persons are given a chance.

Marcelo’s family has been slower than Marcelo in fully recognizing his new-found abilities, but it is coming around. Marcelo now alternates between spending a few weeks at home and a few weeks at the center. He is free to come and go as he chooses. And for the most part he now seems happy. Luis has also returned home happier and more self-confident.

PROJIMO may in a sense be an “institution,” but it is more like a cooperative run by a constantly changing collective of young disabled people. One of PROJIMO’s main functions is to help families of disabled children learn to meet their children’s needs in their own homes. But when such needs are more than the family can cope with, PROJIMO often is able to offer a viable alternative. In the eight years that PROJIMO has been functioning, it has served as a temporary “home away from home” for more than a thousand youngsters.

Many (not all) of these young people have loved their experiences at PROJIMO, and have grown as a result of them. From the day they arrive, all who come to the program are asked to help out with whatever tasks they are capable of doing, and thus begin to develop new skill. Some of the older young people choose to stay on in order to learn further skills and to help others. When they return to their own villages and communities, they often reach out to other disabled people there. And so the process of good will, self-help, and empowerment spreads.

PROJIMO is an example of community-based rehabilitation in which the primary community is formed by disabled persons themselves. HW

NEWS FROM THE MÉXICO PROJECTS

Roberto Fajardo’s Report on Piaxtla: Farmworkers Grow Dry-Season Crop

Roberto Fajardo has worked with the Piaxtla primary health care program for seventeen years, and has been one of its leaders for the past ten years. He first came to Piaxtla at the age of fourteen as a patient, carried on a stretcher from a neighboring village. In the course of his long recovery from a severe case of juvenile arthritis that had completely immobilized him, Roberto helped the health workers with various tasks and began to learn health care skills; when his treatment was over, he stayed on to work with the program.

During a visit to the Hesperian Foundation in July, Roberto discussed Piaxtla’s recent achievements, noting in particular the program’s growing emphasis on the underlying social and political causes of health problems. This focus has led the Piaxtla team to become involved in helping local villagers to organize in defense of their rights. The team has come to feel that campesinos will not improve their health significantly until they empower themselves, raise their standard of living, and put an end to the exploitation and repression they currently suffer. Here are some of the highlights of what Roberto reported.

For some time now, Piaxtla has been working with a farmworkers organization. Over the past several years, this group of poor farmers, insisting on its rights under the Mexican constitution’s agrarian reform provisions, has managed to reclaim a fertile land tract that was being illegally held by wealthy landowners. For the last three years, the farmers have been trying to install an irrigation system that would enable them to grow a second crop of corn and beans during the dry season. In the winter of 1987-88, the group bought an irrigation pump with a grant from the German organization Bread for the World. The campesinos worked enthusiastically to produce a crop during that dry-season, but the effort failed because they were not familiar with dry-season farming techniques.

The campesino organizers were determined to try again, however. They decided that they needed more pumping equipment, so Roberto and two farmers who had never been to México City before travelled to the capital and applied in person for a grant from the Dutch embassy. Before the next dry season (1988-89), the team learned that their request had been approved.

But the campesino organizers found that, even after hearing this good news, most of the farmers were too discouraged by the previous year’s failure to try again. Roberto ended up working with a very small group (about six farmers) to cultivate a little plot of land With the help of Pablo Chávez of the health team, who has experience growing dry-season vegetables, they managed to raise a magnificent crop of corn and beans.

Because of this successful experiment, many campesinos want to participate in the project this coming dry season. The farmworkers organization is eager to plant all the river bottom land that has been recovered from the big landowners. The lesson the group learned from this experience was that it should start small. By working out problems and achieving successes at a small-scale level, the group can show the campesinos that a project will work on a larger scale. An overly ambitious start, on the other hand, can result in a disappointing failure, jeopardizing the project’s survival.

The farmers’ success in growing this second, dry season crop has meant better nutrition for the villagers and thus less illness and death in the community. It has inspired the campesino organization to continue its struggle to reclaim lands illegally held by large landholders. As a start, the group has brought in a government engineer to survey the size of these tracts.

Update on Other Piaxtla Programs

-

Piaxtla continues to move forward with several other innovative community programs. These include a corn bank, a chicken-raising enterprise, and a family vegetable garden project. The campesinos have plans to set up a common credit fund in the near future.

-

The Piaxtla health workers have also helped get a primary health care program under way in the nearby Huachimetas area, located in the state of Durango. Because of its isolation and inaccessibility, this vast region containing same 100 ranches and 8,000 inhabitants is completely without government medical services. ‘The Piaxtla team has trained two health promoters from Huachimetas, and Piaxtla staff regularly visit the new program to help upgrade the skills of the local workers.

-

Piaxtla continues to carry out exchanges with other community health Projects, both within México and abroad. An example of this is the recent visit to Alaska by Miguel Angel Alvarez, a long-time Piaxtla health worker. In June 1988, Miguel Angel led a workshop at the annual meeting of the National Council for International Health in Washington, D.C. A representative from a group of Alaskan health promoters who vas present was so favorably impressed with Miguel Angel’s presentation that he invited him to visit their program; which works with the indigenous peoples of that state. This past summer Miguel Angel was able to take a little time off from his work in Ajoya to visit the program and teach a mini-course on “Training Community Health Workers.”

-

The Piaxtla health workers have joined the PROJIMO team to start a program for elderly people in Ajoya and the surrounding region. So far the two teams have held several meetings with older members of the community, who have selected leaders from among themselves to coordinate the program’s initiatives. Meetings have been held to an elderly carpenter’s home, which the old people’s group has made wheelchair accessible. The community has also given the group an orchard to tends its harvest will provide them with badly needed income. The project is coordinating its efforts with other programs designed for the elderly. The Hesperian Foundation and the México projects hope that a new publication, a kind of Where There Is No Doctor geared specifically to the needs of the elderly, will eventually grow out of the experience gained from this project.

PROJIMO Report: Helping the Spinal-Cord Injured

Project PROJIMO, the rehabilitation center for disabled people founded in 1981 as an outgrowth of Piaxtla’s work, continues to grow in scope and reputation.

One of PROJIMO’s biggest challenges has been to meet the varied needs of spinal-cord inured children and young adults. In developing, countries, 90% of paraplegics and nearly all quadriplegics die within one or two ears after their initial injury. PROJIMO’s efforts are proving that rehabilitation of spinal-cord injured persons is possible at the village level, and at relatively low cost. To date, the project has served over 100 people with spinal cord injuries. Nearly all of these persons were completely dependent and had life-threatening pressure sores when they first came to PROJIMO. Most of them have made remarkable advances. Many feel so welcome and accepted in the PROJIMO community that they stay on to act as peer counselors to newcomers, to work in the wheelchair workshop, or to take on other jobs using skills learned at PROJIMO as part of their rehabilitation.

Since PROJIMO is still the only center in México that offers a full range of services to the disabled, people in need of care now come there from many different parts of the country. PROJIMO has helped disabled people from eleven of the country’s 32 states, and from urban as well as rural areas.

In recent years, PROJIMO has been supplying appliances to three rehabilitation projects in Sinaloa, two of them sponsored by the Mexican government. The PROJIMO team provides these groups with orthopedic aids that are not only less expensive than those made by professional technicians m the city but often better made, lighter, and more appropriate to local conditions. PROJIMO is able to sell such appliances at one-third what they cost in the cities and still make enough money to cover production costs and generate some income for the project. Due in part to the demand from these urban programs, production of artificial limbs, orthopedic appliances, and wheelchairs at PROJIMO has increased dramatically in the last two years.

PROJIMO’s work has been receiving increasing recognition from government rehabilitation programs in Sinaloa, the state in which Ajoya is located. After a recent visit to PROJIMO, the coordinator of the government rehabilitation programs in Sinaloa was so impressed that he is now planning to refer disabled people from throughout the state to the project for orthopedic appliances and other services.

The experience of visiting and working with PROJIMO led the director of the Center for Rehabilitation and Special Education (CREE), a federal government program based in Culiacán, to launch an outreach program consisting of 15 small community-based rehabilitation centers across the state. The director thought so highly of PROJIMO’s work that he asked the project to join this network, offering its workers three times their present salary if they agreed to become part of the government program. The team, however, has been reluctant to place itself under government control. As one of the team members explained to the government director:

We value our independence at PROJIMO. As disabled persons, since we have begun to work at PROJIMO we feel like we have escaped from a prison—a prison into which society put us, and perhaps partly into which we put ourselves. We delight m our new freedom and in running our own program. We know we make lots of mistakes, but at least they are our own mistakes, and together we look for our own solutions. We are happy to cooperate with the government program in any way we can, and appreciate your help, goodwill, and advice. But we want to be our own bosses, in charge of our own lives and our own work. Can you understand how important that is to us? We want to be free!

PROJIMO Entering into Exchanges with Rehabilitation Programs Around the World

Word of PROJIMO has spread far beyond Mexico’s borders. The project has been visited by rehabilitation workers from around the world, including Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, Panama, Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil, India, Burma, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, South Africa, Zimbabwe, England, Sweden, Germany, Canada, and the U.S.

PROJIMO has entered into an ongoing exchange with NORM, a disabled persons’ project in the Bacolod region of the Philippines. This past spring, David Thomforde, an American physiotherapist who has worked extensively with PROJIMO, visited NORM for three months to share his experience and act as an informal consultant. This was followed by a three-month visit to PROJIMO by Lowell Raner, a disabled leader of NORFI. Lowell came to learn brace-making and other rehabilitation skills, while offering in return his own wealth of practical experience and creativity. He was particularly helpful m the PROJIMO toy shop, where he helped invent some imaginative new puzzle designs. Lowell also taught a course in the repair of electronic equipment to disabled people from neighboring communities.

PROJIMO’s Example Inspires New Programs Elsewhere in Mexico

PROJIMO’s example has provided ideas and inspiration that have been instrumental in the launching of a number of other community-based rehabilitation programs in various areas of Mexico. These include Project Más Válidos (“more valid,” as opposed to “invalid”) in the town of Culiacán. El Proyecto Pitillal in a barrio on the outskirts of Puerto Vallarta, and a project in Mazatlán. Another program is just starting up in a squatter settlement of México City. Disabled leaders from all these programs have received on-the-job training at PROJIMO. HW

PROJIMO Needs Your Help!

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of PROJIMO is that it accomplishes so much while operating on a shoestring: its entire annual budget amounts to what it costs to treat a SINGLE spinal cord injured patient for a year in the U.S. But as Mexico’s economic crisis has worsened and its cost of living has soared, the project’s expenses have inevitably risen. Many poor Mexicans can barely feed their families, let alone care for a disabled child. The PROJIMO workers frequently see cases where children paralyzed by polo who had begun to walk using braces have to go back to crawling; when they outgrow their braces, their parents simply cannot afford new ones.

Because of the growing economic crisis, more and more of the disabled people who come to PROJIMO lack the resources to pay even its low fees arid must be seen free of charge. PROJIMO needs your help if it is to continue its policy of serving all who come through its doors, regardless of their ability to pay. If you can, please help us.

‘War on Drugs’ Leads to Human Rights Abuses in Mexican Village

On August 30,1989, at about 5:00 A.M., a group of a proximately 25 soldiers from the Octavo Batallón de Infantería based in San Ignacio, Sinaloa, Mexico, descended on the small village of Lodasál, at the edge of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Without warning, the soldiers forced entry into 22 of the 25 huts in the village. They rousted the men and boys from their beds and pushed them out into the dark. When one man tripped on his sandal strap, the soldiers accused him of trying to escape, and beat him with their rifles. The soldiers shoved one girl against a tree so hard that her face was cut. (She showed me the injury three days later.)

Eighteen of the men were taken by truck to the soldier’s cuartel (barracks) in the town of San Ignacio, about four miles away. The soldiers began to beat some of them with their fists, rifles, and heavy sticks, trying to force them to admit that they were growing marijuana. Eight of the men and boys were beaten, some of them so severely that days later they could barely walk. Yet none admitted to growing drugs, and, according to the people of Lodasál, this year no one has planted drugs in that area.

After intensive beatings and questioning, 12 of the men were transported back to Lodasál by the soldiers, and made to accompany them on a search of the countryside for plantings of marijuana. Some of the men were forced to march ahead of the soldiers carting heavy rocks, until some became so exhausted they staggered and fell. According to the villagers’ reports, no plantings were found.

One 20-year-old youth, Gregorio Ribota, and a man, Ricardo Gonzáles, were taken by soldiers into the forest about three miles from San Ignacio (near the entry of the road to El Chaco), where they were severely beaten with heavy poles until they were nearly unconscious. Then they were tied up with their hands behind their backs, and blindfolded. The soldiers left them in this remote spot, bound and blindfolded, telling them that under no circumstances were they to report what had happened to them. They were told that if they were even seen in San Ignacio or Mazatlán (the closest city), they would be thrown in jail, and that the soldiers would also come after their family members. After the soldiers left, the two captives managed to wriggle near to each other and to untie each others’ ropes. Three days later Gregorio showed me the large bruises and blood clots on his back, hips, and upper legs. A week later he told me that the pain in one hip was getting worse.

Three of the men who were taken from their homes in Lodasál were kept in custody at the soldiers’ quarters in San Ignacio while the search for marijuana fields was taking place (on August 30). These prisoners were Liberato Ribota Melero (age 53), his son Margarito Ribota Virrey, and a neighbor, Roberto García Martínez. The first two were the father and brother of Gregorio Ribota, mentioned previously.

Evidently the decision had been made ahead of time that these three would be prosecuted as drug growers, for—unlike the others who were abducted from their huts—they were not beaten or tortured in any way that would leave visible signs, which might be used in their defense or to bring charges against the soldiers. At close to midnight on August 30, soldiers took the three prisoners to Mazatlán.

According to a San Ignacio municipal policeman who saw them being taken away, the men were transported lying face down in the back of a truck, with their hands tied behind their backs. Their families were told nothing.

Eight of the men and boys were beaten, some of them so severely that days later they could barely walk.

The following day, family members looked for the three prisoners and discovered that they were in the jail ward of the La Loma Travesada military quarters m Mazatlán. However, when the families went there and asked to see the prisoners, they were turned away.

Returning to San Ignacio, the family members went to a lawyer for an amparo—which corresponds somewhat to a writ of habeas corpus—to get the prisoners transferred from the soldiers’ barracks to a jail cell under the auspices of the Ministerio Público (Justice Department). The lawyer charged the families 500,000 pesos (US$200) for the amparo. To come up with the money, the Ribota family had to sell their chickens and pigs and borrow from neighbors. It may take the family years to pay back the debt.

On September 1, more than two days after their arrest, the three prisoners were transferred from the soldiers’ quarters to the Ministerio Público, where family members were able to see them briefly. The prisoners said they had been given nothing to eat for the three days they had been kept by the soldiers.

On September 2, an article appeared in the Mazatlán newspaper, Noroeste, titled “3 plantíos de ‘yerba’” (“Three Pot Plantations Destroyed”). The article states that the three men were in the drug fields in the Arroyo de los Mimbres, near Lodasál, when the soldiers arrived and surrounded the fields, so that when the men ran they were stopped by the soldiers. (In fact, the men were dragged from their beds in their huts.) The article goes on to say that Liberato Ribota confessed to having been growing the drugs for the past 7 years, and that the other two prisoners confessed to helping him harvest and guard the crops. (In fact, Liberato and his family only moved to the area a year ago.) The article even gives the dimensions of five marijuana plantations in the Arroyo de Los Mimbres, and estimates that the crop the soldiers allegedly destroyed, which was supposedly planted with ten marijuana plants per square meter, would have yielded five tons of the drug. (According to everyone we talked to in Lodasál, however, in their search the soldiers found no marijuana fields at all.)

He estimated that in the Culiacán jails alone, approximately 10,000 campesinos are being detained. The recent escalation of arrests of campesinos is part of an attempt by the Mexican Government to present a cleaned-up image to Washington in order to convince the Bush Administration that México is serious about fighting the "war on drugs."

On questioning the people of Lodasál, I became convinced that they were telling the truth, and that the soldiers had committed a variety of crimes against innocent people, ranging from breaking and entering to theft, abduction, torture, false incrimination, unjustifiable detention, and failure to reveal the location of prisoners to family members. The Ribotas, whom I had known well when they lived in Ajoya before they moved to Lodasál, were desperate.

And with good reason. This was the third time in less than a year that the Ribota family has been falsely arrested, tortured, or abused by soldiers from San Ignacio. The first incident took place on December 4, 1988, when soldiers raided Lodasál, seizing men from their houses and putting them on trucks. According to Gregorio, the soldiers made the men jump out one at a time while the truck was moving at about 20 miles an hour. When Liberato was forced to jump, his head hit the pavement so hard that it was cut open and became very swollen. He remained very dizzy for a week afterwards. Gregorio fared better: he escaped with only bruises and cut hands. The soldiers also harassed members of the Barraza, Emilio Bastidas, and Victoriano Murillo families.

The second incident occurred in March of this year. One day when Liberato and his 13-year-old son Leopoldo were cutting wood in the forest near their homes, they were apprehended by another group of soldiers. The soldiers repeatedly punched the gild in the stomach in front of his father, and then held the father’s head under water “to get him to talk,” although the two had committed no crimes.

Deciding to try to help these persecuted people obtain justice, other concerned persons and I accompanied Liberato’s wife and 20-year-old son Gregorio (who had been beaten and left tied in the woos) to Culiacán, the state capital of Sinaloa. We spoke with the head of the Human Rights Organization based at the University there, and trough friends in the press arranged for the wife and son to speak with the general of the army detachment based in Culiacán. The general told them that since the prisoners had been handed over to the Ministerio Público, he was no longer in a position to take any action (even though the soldiers under his chain of command had, within the week, committed multiple abuses, including torture, and have, since the arrests, made new threats against inhabitants of Lodasál).

Before going to the state capital, the families of the prisoners prepared a statement describing the injustices they had suffered at the hands of the soldiers. Many people in the village had agreed to sign such a statement. But when it came to actually signing it, nobody dared. They were afraid the soldiers would come back and give them another “calentada” (roughing up) if anyone protested, as they had very clearly threatened to do.

While in Culiacán we sought advice from a journalist who for many years has been studying the workings of drug production and trade in western Mexico. He was not optimistic about the chances that our falsely accused friends would obtain justice. He estimated that in the Culiacán jails alone, approximately 10,000 campesinos are being detained under similar circumstances, while soldiers and other government officials continue (as they have for many years) to grow or oversee huge clandestine plantations of illicit drugs. In his view, the recent escalation of arrests of campesinos, many of them falsely charged with drug growing, is part of an attempt by the Mexican Government to present a cleaned up image to Washington in order to convince the Bush Administration that México is serious about fighting the “war on drugs.”

Our reporter friend also made it clear that people have good reason to fear the threats of the soldiers if they try to protest their abuses. As an example, he told us that he had learned of an incident in Chihuahua where soldiers had entered a small village school and had beaten the children to get them to tell where their fathers were growing drugs. The school teacher, although ordered to remain silent under threat, reported the soldiers’ abuses. A few days later, a helicopter landed next to the schoolhouse, soldiers abducted the teacher, took him high in the air, and then pushed him out.

The hearing for the three prisoners from Lodasál was first scheduled for 2:00 p.m. on September 8. That morning I went to Mazatlán to talk with the defensora or defense attorney appointed by the court to represent the prisoners. I was accompanied by a doctor who has worked for many years in the Sierra Madre and who, like me, has treated many victims of abuse by the military and state police. The defensora knew of Project Piaxtla and my book, Where There is No Doctor, and was very friendly. She told us that she, too, was convinced that the three defendants were innocent, but said that in the present climate it would be very difficult to get a ruling in their favor. She suggested we speak directly with the judge who would be hearing the case.

We did. Judge Cantú Baraja was very friendly and listened to us for about ten minutes, as we presented all the information that we had gathered. But then he told us that, regardless of what we said, the case was unlikely to go in favor of the defendants. Although we claimed the soldiers had tortured many of the men they had abducted, he pointed out that the prisoners had been carefully examined for signs of physical abuse, and none had been found. Furthermore, he said, one of the prisoners, Roberto García, had confessed before the judge himself, under no force, pressure, or threats, stating that he had assisted the other two prisoners in their marijuana fields. To prove this, the judge pulled from his files the text of Roberto’s signed declaration.

The young doctor and I were badly shaken. Could it be that so many people had completely deceived us, and convinced us to stick out our necks to defend them when they had actually committed the crimes they so fiercely denied? We left the judge’s office shaking our heads. How could we have been so gullible?

Accompanied by Liberato’s wife and son, we met again with the defensora and told her of Roberto’s signed confession. It was the first she had heard of it, and for a minute it took her by surprise. But after a moment’s thought, she told us she was convinced that Roberto had been tricked—as have so many others like him.

What happens, she explained, is that when the soldiers turn a prisoner over to the Ministerio Público, an officer of the Ministerio takes a declaration from the prisoner. No force or pressure is applied, and the prisoner is encouraged to make a true statement from his point of view. As the prisoner talks, a secretary busily types the prisoner’s declaration on a typewriter. When the prisoner is done speaking, he is asked if everything he has said is true and if he has anything he wants to add. When the prisoner says his declaration is true and complete, the declaration is pulled from the typewriter and the prisoner told to sign it—but without being given time to read it.

The catch is that the secretary, who the prisoner thinks is writing down his declaration, is actually copying the soldiers’ report, complete with falsified confession. The defensora told us that in some cases she has been able to prove this because the supposed “declaration” has followed the exact wording of the soldiers’ report, sometimes for several paragraphs.

The defensora told us that while Roberto had evidently fallen for the trick and signed the document, Margarito, who, she said, has a quick mind, had managed to read part of his “declaration” when he was asked to sign it, and had protested to her that what was written on it was not what he had said.

“But the judge said Roberto had confessed directly before him!’ we observed.

“Yes,” said the defensora, “but what he probably did was simply ask Roberto if the declaration he signed is accurate, and if he signed it voluntarily, without being forced.”

“Does the judge know that declarations are being falsified and prisoners tricked into signing them?” we asked.

“Of course he knows,” she replied. “But he’s afraid to buck the system. The military is very strong, and at the moment the government wants to see a lot of convictions of drug growers and traffickers. The judge understands what’s expected of him. And he’s aware of the political climate. If he wants to keep his position and to get ahead, it’s better not to make waves unnecessarily.”

“But what can be done to help the people who are being victimized?” we asked.

“Isn’t there some way to get an independent inspection of the area where the soldiers claim they destroyed the marijuana fields, to prove that they are lying?” asked Gregorio (Liberato’s son, the young man who had been so severely beaten by the soldiers).

The defensora said she could ask for an official, but independent, investigation to determine whether or not the reported marijuana plantations had actually existed. But she said it would be expensive.

“And if the investigation shows that no signs of destroyed plantings exist where the soldiers say they destroyed them, and the prisoners are proven innocent, who will have to pay the costs of the investigation?” we asked.

“The prisoners and their families,” was the reply.

“That doesn’t seem very fair,” we commented.

“No, but that’s how it is.”

We talked for a moment with Gregorio and his mother, and asked the defensora to request the investigation. One way or another, we would try to come up with the money.

The judge conducted the investigation and found no evidence whatsoever that any marijuana plantings had ever been present in the areas designated by the soldiers.

The defensora also told us that the judge had decided to release Margarito and Roberto bajo fianza (more or less on non-refundable bail). They would have to pay a sizable sum of money and report back to Mazatlán every week for the duration of their sentence—which, according to the article in Noroeste, would be from 10 to 25 years. (The defensora said it might be as little as 6 months.) She told us that Margarito and Roberto had appealed the decision, but she recommended that we request the appeal be revoked. She explained that if the two were released bajo fianza and then the appeal was approved, the superior judge assuming the case might have them picked up and brought in again by the soldiers. And in the end they might have to serve a prison term. She recognized that accepting the suspended sentence and paying the fianza was a little like paying a bribe, but she felt that under the circumstances it was the safest and cheapest alternative. Reluctantly, we (family and friends) took her advice. But it will still be very hard on the family. Travel into Mazatlán one day a week will cost the equivalent of nearly one day’s work, plus the loss of the work that could have been done in that day. As it is, the family barely has enough to feed its children.

In talking with Margarito after his release, I have learned that the soldiers tortured him, Roberto, and Liberato in ways less likely to leave physical marks, as distinct from the methods they used on those they detained only briefly. In San Ignacio, the three men were hit in the stomach and boxed on the ears with cupped hands. The soldiers also held plastic bags tightly around their heads until they began to asphyxiate—a variation of the traditional “water treatment.”

According to Margarito, when he, Roberto, and Liberato were taken to the La Loma barracks in Mazatlán, they were ordered to sign a document presumably a confession. When they asked to read it before signing, the soldiers cursed them, grabbed them by the hair, and hit them in the face repeatedly. They banged Liberato’s face into the edge of a door, producing a cut on his nose which has left an ugly scar.

Margarito also reports that when the Ministerio Público questioned the soldiers about the offenses of the prisoners, one soldier claimed that he had caught Margarito trying to run out of the back of his house, while another gave a contradictory story, saying that he had found Margarito in a marijuana plantation supposedly located two miles from the village of Lodasál.

Two weeks after the arrests, the public defender, acting at our insistence, demanded an independent investigation of the soldiers’ charges. In response, the judge of the Sixth District in Mazatlán sent a request to the judge of the “Primera Instancia” of San Ignacio, Sinaloa, asking him to carry out an inspection to determine whether any evidence existed of the marijuana plantations where the soldiers claimed to have caught the three prisoners. According to a document dated September 27 and signed by the judge in San Ignacio, the judge conducted the investigation and found no evidence whatever that any marijuana plantings had ever been present in the areas designated by the soldiers. This finding by the judge in San Ignacio definitively bears out the claims of the people of Lodasál that the soldiers had fabricated heir charges, had arrested and tortured citizens of Lodasál without cause, and had provided falsified statements incriminating the three prisoners who were taken to Mazatlán and turned over to the Ministerio Público.

To date, the Ministerio Público has made no move to change its verdict, despite having the document from the judge in San Ignacio which proves the prisoners innocent. Margarito and Roberto are still on suspended sentence, and Liberato Ribota Melero remains in jail.

As representatives of efforts to support international and community health, we of the Hesperian Foundation are publicizing the story of this human rights violation, not only to help bring justice (limited as it may be) to the people of Lodasál, but also to help expose the terrible abuses that are resulting throughout México and Latin America from the “big stick” approach being taken by the Bush Administration in its so-called “war on drugs.”

Both the U.S. and Mexican governments have their own thinly disguised ulterior motives for waging a high-visibility but low-return “war on drugs.”

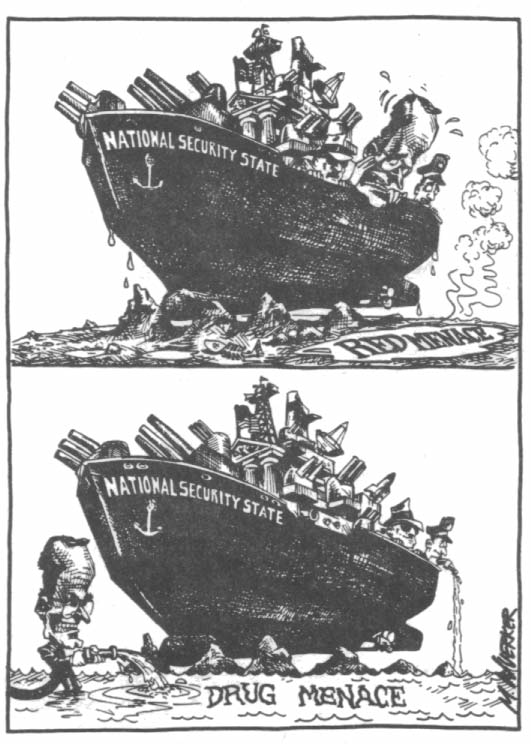

The Bush Administration, needing a more plausible bogeyman, has seized on the drug crisis as the great new threat to our national security.

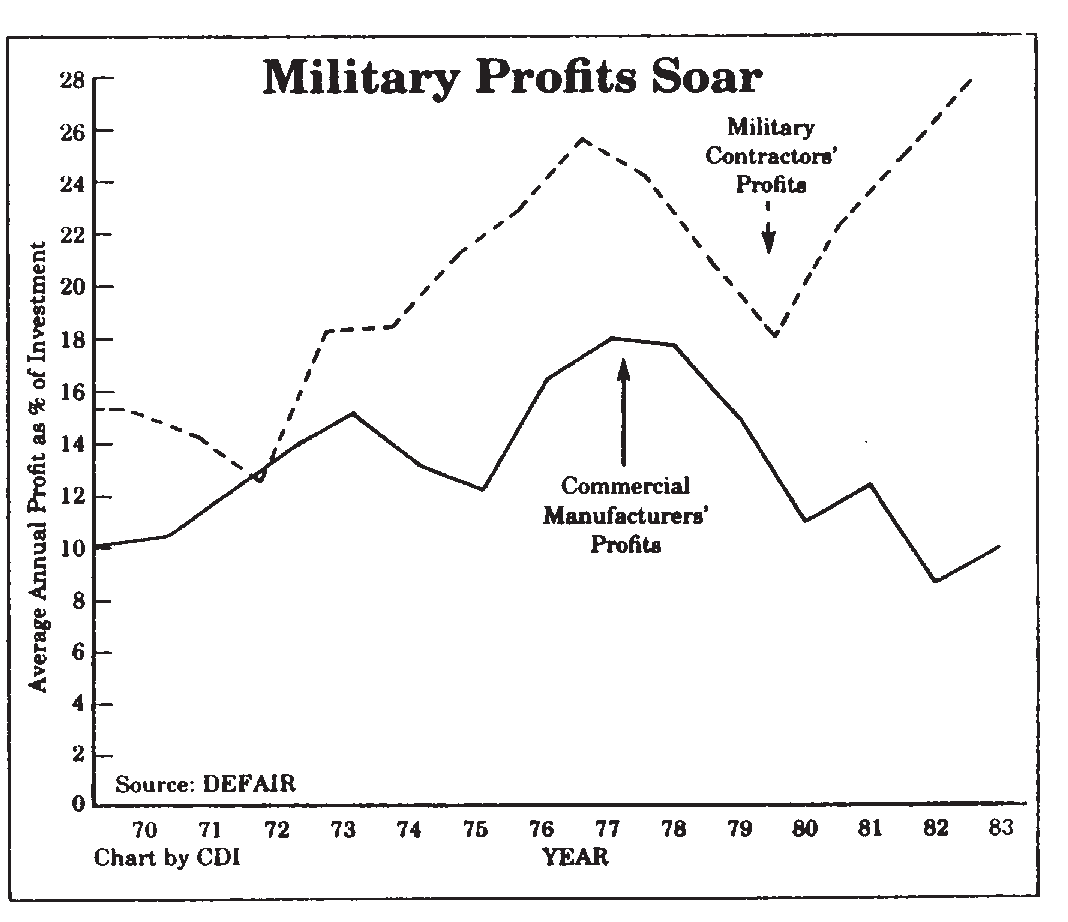

The Bush Administration is milking the “drug crisis” for all it’s worth. In order to justify their huge military expenditures to the U.S. public and to maintain the waning global grip of the military-industrial complex, the powers-that-be in Washington need to point to a dangerous enemy that perpetually threatens our national security. Under Gorbachev, the Soviet Union no longer lives up to the old panic-generating image of the “evil empire.” Indeed, many who critically examine the facts now view the Soviet Union as considerably less threatening to global security than the U.S. During the 1980s, therefore, the focus on the Soviet Union as the primary threat to U.S. national security partially shied to liberation movements in the Third World, which the Reagan Administration imaginatively portrayed as “enemies of democracy.” But more and more nations are daring to criticize Washington for its consistent attacks on small Third World nations struggling for fairer systems and self-determination. So the Bush Administration, needing a more plausible bogeyman, has seized on the drug crisis as the great new threat to our national security.

For its part, the Salinas Administration in México is extremely vulnerable to U.S. pressure. It desperately needs Washington’s cooperation in order to cope with its huge foreign debt. President Salinas and his advisors know very well that if they do anything to displease the Bush Administration, it can retaliate by taking a hard line stance on Mexico’s debt repayment terms. Through its dominant influence in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, the U.S. government could at any moment push Mexico’s shaky economy over the brink into complete collapse. So the Salinas government is trying hard to comply with Bush’s demands. Since the “war on drugs’ has become Washington’s number-one priority, and since U.S. politicians frequently charge the Mexican government with laxness and corruption in this area, the Salinas Administration is doing its best to create the impression that it is serious about cracking down on the drug trade. Because the Mexican government cannot afford to launch a genuine assault on the narcotics industry, its efforts to display a tough image consist mainly of arbitrary raids and arrests like the ones that took place at Lodasál. While such actions may look good on paper, in reality they victimize powerless—and often innocent- poor people while leaving most of the drug lords and their lucrative racket untouched. †

† The arrest of Felix Gallardo earlier this year illustrates Mexico’s attempt to put up a facade of being tough on drugs to ward off U.S . pressure. On April 10 The New York Times reported that the Bush Administration was considering recommending that the International Monetary Fund refuse a $3.5 billion bail-out loan that México needed to keep from defaulting on its $100 billion foreign debt. The next day, the Times ran a front-page article telling how Gallardo, one of Mexico’s biggest drug lords, had been jailed along with scores of state police in the biggest “bust” of government officials in the country’s history. ( A few days later, most of the higher ranking officials who had been arrested were quietly released.) On the day following the arrests, the Times announced that the IMF had approved the crucial loan.

The fact of the matter is that neither the Salinas nor the Bush Administration really want to stop the flow of drugs across the border. México needs its drug earnings (which accounted for 70% of its export earnings through the 1980’s, according to a State Department study) to help service its debt. And Washington uses drug trafficking into the U.S. to finance its covert operations in the Third World without having to go through Congressional channels. Besides, if the drug threat disappeared, the Bush Administration would lose its latest pretext for manipulating and militarizing Third World nations.

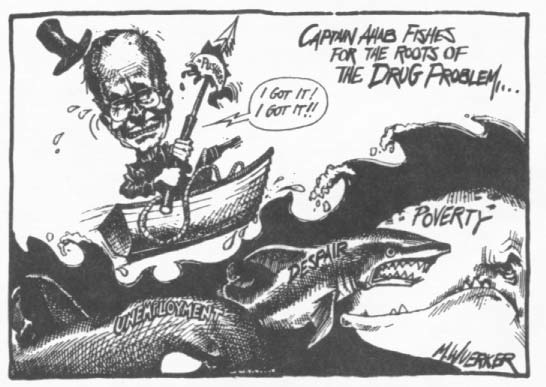

To be effective, efforts to bring the drug crisis under control must tackle the real causes of drug use and trafficking—despair, alienation, and unemployment, along with the poverty and powerlessness that lie at the roots of these problems. This requires far reaching structural changes designed to bring about a society that no longer marginalizes and impoverishes a substantial portion of the population. Also needed are steps to ban covert operations (routinely financed through drug trafficking), to cancel suffocating foreign debts which make drug trafficking an economic necessity, and to redirect military budgets to meet basic needs. In the final analysis, the only real cure for the drug crisis is a new global economic order which reduces the gap between rich and poor both within and between nations.

The far-reaching transformation of our social structures and economic order that are necessary to effectively reduce `the drug problem’ will be a long time coming—and they will certainly not be brought closer by the Bush Administration.

In the meantime, it is important that human rights groups, the United Nations, and the international community be alerted to the widespread suffering that is resulting from Bush’s heavy-handed, enforcement-oriented approach to combating drugs. The thousands of innocent people who are being victimized need some kind of defense. In countries like Mexico, a watchdog or review process of some sort is needed, perhaps through the United Nations or the World Court. And here at home we need to let our Congressional representatives know what is really happening, so that our government stops contributing to the abuses of marginalized people in poor countries by further arming and strengthening security forces that have a long record of repression, corruption, and—yes!—collusion in drug trafficking.

If and when Washington becomes serious about fighting a “war on drugs,” it should start by taking a hard look at the report recently issued by the Kerry Commission (the Senate Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations, which has compiled a wealth of evidence implicating various U.S. government agencies, especially the CIA, in using drug trafficking to advance their covert operations and political goals), and then moving to clean up its own act. There is a substantial amount of evidence that then-Vice President George Bush was a key person indirectly facilitating, or at least turning a blind eye toward, the clandestine drugs-for-arms swaps in support of the Nicaraguan Contras. If Congress were really sincere about attacking the drug problem, it would stop going after small-time dealers and innocent people and instead turn its attention to the key players who bear the major responsibility for the rising tide of drugs flowing into the U.S., including President Bush himself. † HW

† Although the mass media carefully steers clear of it, the evidence against Bush is considerable and well-documented. For those who are interested, one of the most comprehensive exposes of Bush s links to CIA drugs-for-arms racketeering can be found in David Barsamian’s “Interview with John Stockwell” in the September 1989 issue of Zeta Magazine. (John Stockwell is an ex-CIA officer who resigned in disgust and has been working since to bring the crimes of the CIA into the open.) An article by Andrew Lang entitled “How Much Did Bush Know?” appearing in the Summer 1989 issue of Convergence (a magazine published by the Christie Institute) further documents Bush’s links to some of the key figures involved in the Contra arms-for-drugs connection. The same issue also contains an article on the Kerry Commission report. This article points out that, while the report’s language was watered down as a result of compromises demanded by the Bush Administration supporters on the subcommittee, it nevertheless clearly states that “senior U.S. policy makers were not immune to the idea that drug money was a perfect solution to the contras’ funding problems.” The evidence pulled together in the report conclusively implicates high-level US officials in these covert drugs-for-arms deals. For an excellent update on these issues, see “Drugs, Iran-Contra, and HIV Infection: The Not-So-Casual Link,” an article by Jay Hatheway in the October 1989 issue of Zeta Magazine. The author links the proliferation of AIDS through widespread drug use to the role of the CIA and the National Security Council in the major increase in drug trafficking into the U.S.

News From the Hesperian Foundation

‘Health for No One by the Year 2000’: A Controversial New Paper by David Werner

In June 1989, David Werner gave a talk at the annual meeting of the National Council for International Health (NCIH), a consortium of U.S. nongovernmental organizations involved in international health and development. His controversial speech, entitled “Health for No One by the Year 2000: The High Cost of Placing `National Security’ Before Global Justice,∞’ provoked a strong reaction. Two-thirds of the audience gave David a standing ovation, while the remainder sat in stony silence.

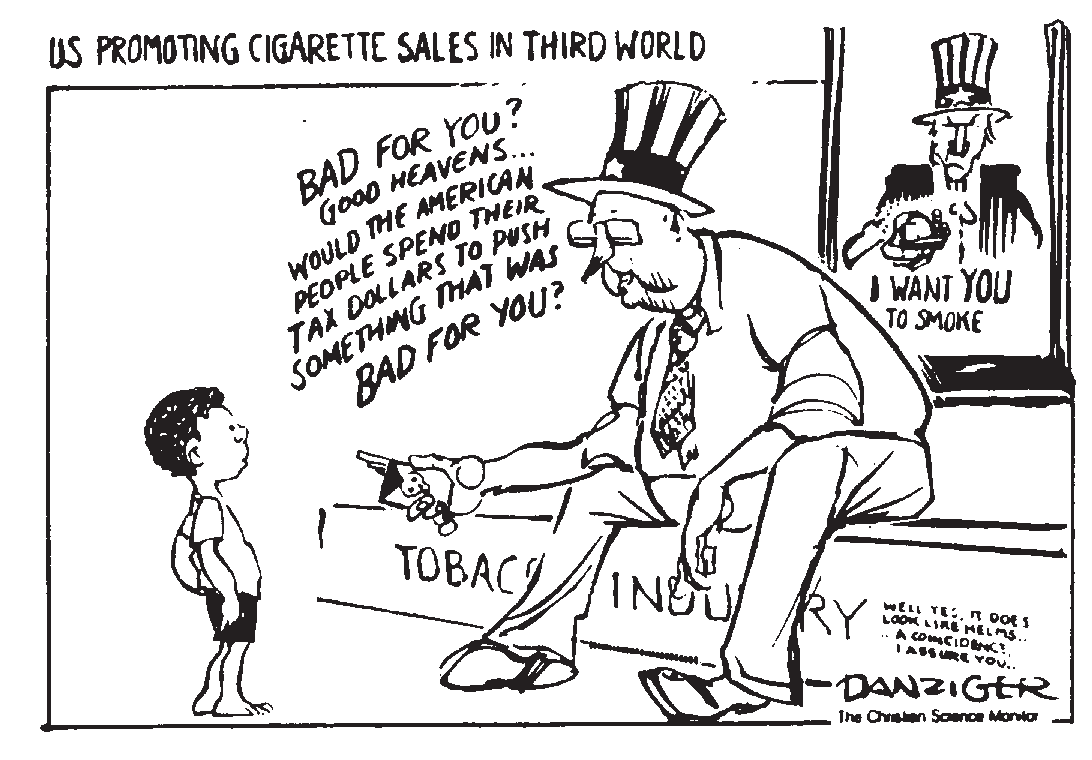

The talk starts out: “Not long ago a high-ranking officer in the World Health Organization (WHO) remarked that the biggest obstacle to health in the world today is the United States of America.” Next comes an expose of how the global power structure determined to a large extent by U.S. foreign policy and the military-industrial complex-consistently places profit ahead of human welfare. As a result of this institutionalized greed, the gap between the rich and the poor is widening, both between countries and within them. Far from moving toward the goal of “health for all,” we are seeing the health and survival of the planet and its people being placed in greater danger than ever before. WHO and UNICEF find themselves blocked in their attempts to deal with the real sources of poor health, such as the unethical conduct of what David calls the “killer industries”; often it is pressure and threats from the U.S. government (which provides 25 percent of their budgets) that stands in the way. So these agencies end up promoting quick-fix, narrow technical approaches rather than confronting the man-made root causes of poverty and poor health.

David goes on to argue that national security has become an obsolete concept, and that we must choose between global security and no security. The talk concludes with a call for a “global revolution” in which the poor and exploited of the world, together with those of us in a more privileged position who share a real commitment to the goal of “health for all,” unite to promote an approach to development that places people before profit, equity and environmental balance before greed and economic growth.

This explosive paper includes an appendix spelling out in detail the vast destruction and human suffering being caused by eight enormously profitable and powerful multinational “killer industries” that have targeted the Third World as their newest, fastest-growing, and most vulnerable market. These include:

-

alcoholic beverages

-

tobacco

-

illegal narcotics

-

pesticides

-

infant formula

-

unnecessary, dangerous, and overpriced medicines

-

arms and military equipment;

-

and international banking (money-lending for profit).

For a copy of the paper, write to HealthWrights. Please send $3.00 to cover our costs.

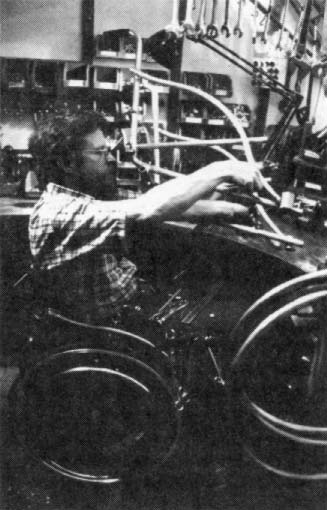

Ralf Hotchkiss Named MacArthur Fellow

On July 13, Ralf Hotchkiss, an advisor to Project PROJIMO and a Hesperian board member, was named one of this year’s 29 MacArthur Fellows. Also known as “Genius Awards,” these prestigious fellowships are given to gifted individuals in a wide variety of fields by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The grants allow recipients complete freedom to work on whatever projects they choose.

Ralf was awarded the fellowship in recognition of his creative and committed work designing wheelchairs for use in the developing world. Millions of disabled people throughout the world lead lives of severely limited mobility and possibilities because they cannot find appropriate, affordable wheelchairs. To help meet this great need, Ralf concentrates on developing wheelchairs that are inexpensive, easy to make with locally available tools and equipment, and suitable for rugged terrain.

Ralf plans to use his grant to continue experimenting with new wheelchair designs, as well as to expand his work with small wheelchair workshops and a growing network of disabled wheelchair builders in the developing world. HW

End Matter

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photos, and Illustrations |