Remembering Marcelo

Last May (2008) Marcelo Acevedo fell ill and rapidly succumbed to brain cancer. The event was briefly noted in our last newsletter, but because Marcelo touched and changed so many people’s lives, we decided to devote this newsletter to his memory. Marcelo was one of the founders and core members of PROJIMO, the Community based rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers in western Mexico. As a disabled person who reached out with his hands and heart to do his very best to help other people, on equal terms, Marcelo was a personification of the highest ideals of the program.

Marcelo as a Child

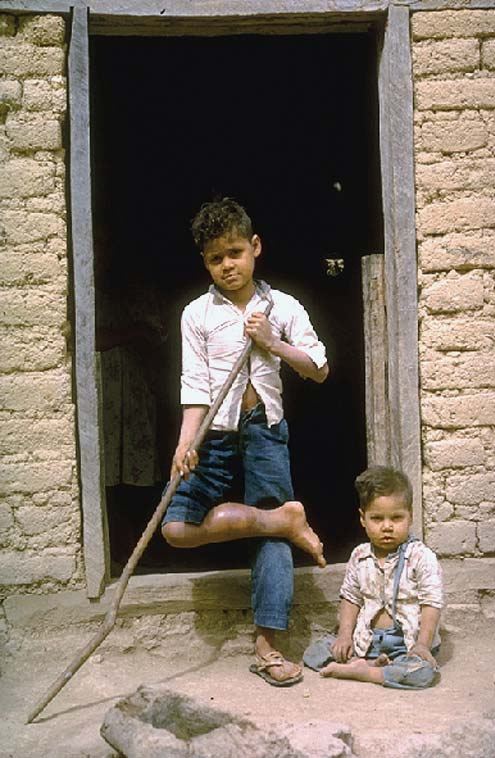

I first met Marcelo when he was 3 years old, in the tiny village of Caballo de Arriba, high in the Sierra Madre, two days by mule-trail from the closest road. This was in the late 1960s, in the early days of Project Piaxtla, the villager-run health program I had helped start in this remote area. I was making the rounds of the outlying villages as the first stage of setting up a vaccination program to protect children against the common contagious diseases of childhood. In those days these readily preventable afflictions—measles, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, and polio—were causing a high incidence of sickness, death, and disability. Arriving at the village after several hours riding along the steep narrow trail of the high sierra, I remember parking my weary mule alongside a small adobe hut on the flank of a deep ravine. Sitting in the dust near the doorway of the hut was a small boy. His spindly legs were incapacitated by polio. His parents welcomed me in, and soon the family became one of those most involved in promoting the [health project]. Within a few years, with the help of families like Marcelo’s, hundreds of square miles of the isolated mountain region were fully immunized. Indeed, with the participation of the local people, polio was eliminated from the remote reaches of the Sierra Madre four years before it was controlled in the cities.

For children like Marcelo, however, the benefits of the polio vaccination were too late. What would be the future of a little boy with paralyzed legs, in a village where people earned their living by farming the steep mountainsides? There wasn’t even a school in the village. Nor, in those early days, did our village health program have the skills or equipment to respond adequately to the needs of disabled children. Nevertheless, we did what we could.

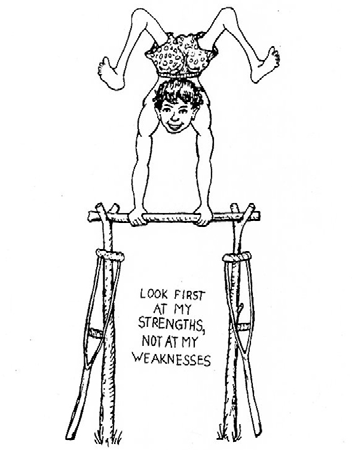

We helped Marcelo to learn to walk with braces and crutches. Because the development of his mind was important to make up for the weakness of his body, when he was 12 years old we arranged for him to study in an “adult education” program in the larger village of Ajoya, where the Piaxtla health program was based. Fortunately the boy had a good mind and a lot of motivation. He got his diploma for primary school in less than one year.

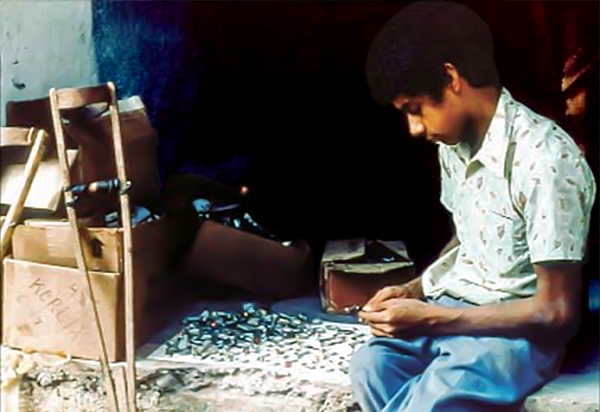

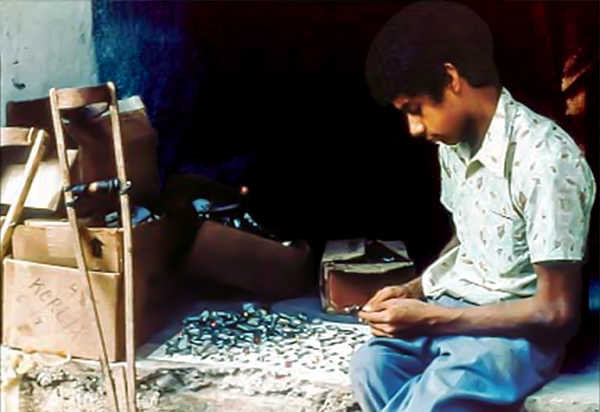

That year happened to be the one preceding the International Year of the Child (1978). Marcelo took the lead in mobilizing other school children in the village to make a unique contribution for child survival, worldwide— namely in the prevention of death from diarrhea. Because dehydration resulting from diarrhea is one of the world’s biggest killers of children, Project Piaxtla had worked hard to develop a simple way that families could combat dehydration at low cost, right in their homes. To this end, the health workers had invented a simple homemade measuring spoon for mixing the proper amounts of sugar and salt in a glassful of water, to make a low-cost, potentially life-saving rehydration drink.

The spoons could be easily made from old bottle caps and scraps of beer or juice cans (which for better or for worse are universally available). If children around the world could learn to make such spoons to prepare a homemade “special drink” when their baby brothers and sisters had diarrhea, we imagined they could save more lives of sick infants than all the doctors put together. The problem was how to teach them to make the spoons. We tried making instruction sheets, but the children found them too complicated. What they needed was a sample spoon they could hold in their hand and say, “I can make this! It’s easy!” So as their contribution to the Year of the Child, the schoolchildren of Ajoya mass produced thousands of these simple spoons. Leading the effort was young Marcelo, who taught other kids how to make them, and who made hundreds himself. We sent the spoons to the Child-to-Child Headquarters in England and from there they were sent to schools around the developing world.

After Marcelo got his Primary School Certificate, the Piaxtla team invited him to train as a junior village health worker. At age 14 he returned to his remote village of Caballo, and for the next 21⁄2 years served his community as a promotor de salud. People soon gained a great deal of respect for him. He worked tirelessly, doing everything from vaccinating children to suturing wounds and delivering babies. Having a disability himself, he always bent over backwards to help those in greatest need. Even in a rainstorm or at night he would bound along the steep trails on his crutches to reach a distant hut in a medical emergency. Everyone learned to appreciate his ability, and pay little attention to his disability.

Marcelo Helps Start PROJIMO

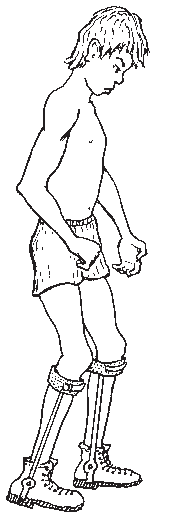

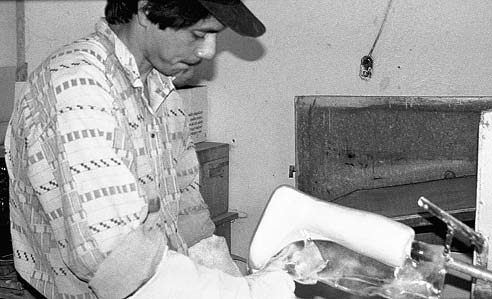

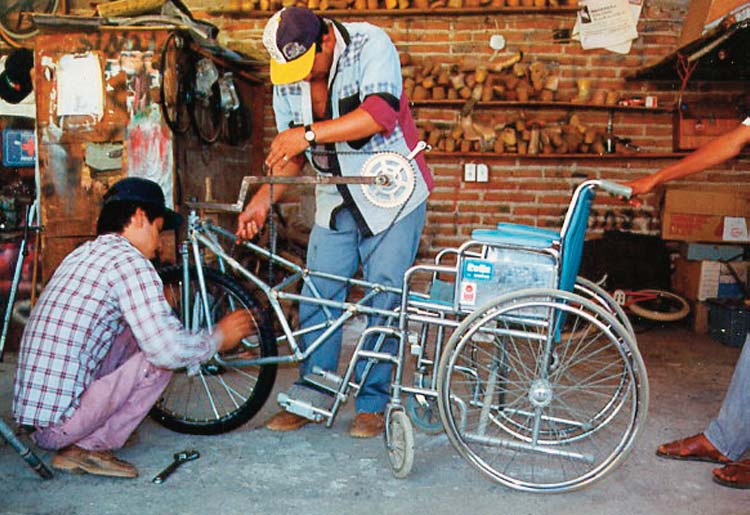

Marcelo continued to serve his village as a health promoter until 1980, when PROJIMO, a Community Based Rehabilitation program run by disabled villagers, began to grow out of the Piaxtla health program. Marcelo, now 17, returned to Ajoya to become one of the new program’s founding members. Because as a crutch user he had such strong, able hands, the team thought he could become a good brace and limb maker. Marcelo was eager to give it a try. Intermittently during the next couple of years he apprenticed in orthotic and prosthetic shops in Mexico and California. With additional help from visiting volunteer orthotists and prosthetists, he gradually became a gifted brace and limb maker.

Although Marcelo only had one year of formal schooling and no formal technical training, he did such a fine job making limbs and orthopedic appliances that for a number of years he “moonlighted” making limbs, prostheses, and orthotics for CREE, the highly professional Center of Rehabilitation and Special Education in the state capital. CREE’s Director said the quality of Marcelo’s work surpassed that of the titled prosthetists and orthotists in the city. I’m convinced this was because Marcelo always put in the extra time and care needed to be sure the devices fitted well and were optimally adapted to each person’s individual needs.

Marcelo was a master craftsperson. But skilled as he was, he remained a very humble and caring person. He got along well with everyone. While he shied away from formal leadership at PROJIMO, he was an excellent arbitrator and peacemaker. At meetings he spoke little, but would listen carefully to everyone. When he did speak always quietly and succinctly—everyone listened to what he had to say—and disputes tended to be resolved more amicably.

With everyone—but especially with those who were poorest or in greatest need—Marcelo always took the time and concern to make sure the assistive devices he created were meticulously adapted to each individual’s particular needs. He was remarkably creative in the problem solving process. No doubt having a disability himself gave him empathy and insight into the needs of others.

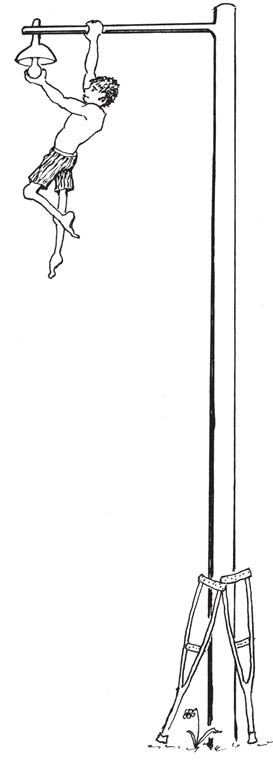

One time a 5-year-old child named Lino, who had spina bifida, was brought to PROJIMO. The boy had learned to walk with a walker, and Mari, the program coordinator, felt he was ready to start walking with crutches. But Lino was afraid. After all, crutches are a lot more unstable than a walker; they wobble this way and that and a child with insecure footing can easily fall. Marcelo remembered how scary this could be from his own childhood. So he invented for Lino a unique walker that could gradually be converted into crutches, without any sudden, frightening transition.

The walker consisted of two forearm crutches, which were connected with cross struts held in place with bolts and butterfly nuts. This way, the nuts could be gradually loosened to make the walker more wobbly and less stable. Then one after another the cross pieces and back supports could be removed—until only the crutches were left. That way the trauma of a sudden change was avoided. This kind of innovation, in which Marcelo accommodated a child’s worries and fears with empathy and creativity, was very characteristic of Marcelo.

Marcelo’s Marriage and Family

When Marcelo returned to the village of Ajoya as a rehab worker, he stayed with a family that had a son with epilepsy who was an apprentice in PROJIMO’s wheelchair-making shop. Also living there was the granddaughter of the householders, named Chayo. Marcelo and Chayo had been playmates since his first stay in Ajoya, years before. Now Marcelo was 17 and Chayo was 14—and the two of them fell in love.

Chayo’s grandmother, Doña Adelina, felt they were too young to be novios—even though she herself had married at age 14. But even more strongly, she didn’t want to have her granddaughter marry “un chueco” (a twisted person; a cripple). There was still a lot of discrimination against disabled persons in those days. So Doña Adelina did her best to keep the young lovers apart. She forbade Chayo to leave the house without a chaperon—and when she caught the girl sneaking out, she beat her. The day arrived when the couple decided to elope. They stole away and hid for three days and nights in a vacant house. On the fourth day, long before dawn, they took off together on foot—Marcelo on his crutches—up the river toward his remote home village of Caballo de Arriba, 40 miles back into the wilderness. Marcelo had arranged for his brothers to meet them half-way, with mules on which to finish their journey.

By mid morning word somehow reached Doña Adelina that the eloping couple had been seen along the trail. As it happened, a squadron of narcotics-control soldiers were camped in Ajoya at the time. Adelina informed the Capitán that Marcelo had “robbed” her underage granddaughter, and the Capitán sent a pickup truck full of soldiers in pursuit of them, upriver.

The soldiers had just left when I got wind of what was happening. I hurried to Doña Adelina to try to convince her to call off the soldiers. After all, marriage of 14-year-olds was not uncommon in those days, and the two young people clearly loved each other. But Doña Adelina, in tears, kept insisting she didn’t want her granddaughter get hitched to a chueco. I kept arguing that the disability didn’t matter. Marcelo was a gentle, kind-hearted person and skilled crafts man. And as a bonus, he wasn’t a drunkard.

Such a combination of qualities was hard to find in young men, and more so in older men, who might court her granddaughter.

At last Doña Adelina gave in, and authorized me to call off the soldiers. I jumped into the old PROJIMO Blazer and drove as fast as I dared upriver on the rocky track, hoping to catch up with the soldiers before they caught up with the runaways.

I was too late. When I was about 12 kilometers upriver, I spotted a cloud of dust far ahead of me, coming my way. It was the soldiers, their mission accomplished. As our two vehicles approached, I hailed them to stop. Marcelo, hands bound behind him, was sitting in the back of the pickup. Chayo, looking more angry than scared, was perched next to him.

I called out to the soldiers, “Doña Adelina says you can let them go! She’s agreed to let them be a couple.” The soldiers laughed good-naturedly and gladly untied their captive. Marcelo and Chayo climbed over into my Blazer.

That was the beginning of a long and eventful marriage. Over the years Chayo and Marcelo had five children— all boys—and all with very different personalities and talents.

Marcelo was one of the most loving, gentle, and devoted fathers I’ve ever known. From the time his children were toddlers, he treated them as equals. They loved to hitch a ride with him on his hand-powered tricycle. From the age of 3 or 4, they would accompany him to the PROJIMO prosthetics shop where they’d sit on the workbench talking and joking with him as he worked. Few fathers are as devoted to their children as was Marcelo, and few children as deeply attached to their father.

Marcelo Persuades Me to Try Braces

I personally benefited from Marcelo’s very able and caring assistance—even though at first I stubbornly refused it. I have an inherited, progressive muscular atrophy (Charcot Marie Tooth Syndrome), which has caused partial paralysis in my hands and lower legs. As a child I was made to use orthopedic appliances against my will, and they caused me a lot of pain and injury. So when I got old enough to have a say in my own life (at about 14) I stopped using the braces. Although my walking gradually became more awkward, I’d refused to consider further appliances. At last Doña Adelina gave in, and authorized me to call off the soldiers. I jumped into the old PROJIMO Blazer and drove as fast as I dared upriver on the rocky track, hoping to catch up with the soldiers before they caught up with the runaways.

Decades later, at PROJIMO, on seeing me hobble across the yard, Marcelo said, “David, I think you could walk better if we fitted you with some plastic braces.”

To which I replied: “No way! I was tortured enough with braces as a kid!”

But Marcelo said, “Maybe the braces didn’t work for you because the specialists didn’t work together with you to figure out what you really needed.” I had to agree.

“How would it be if you and I work together, experimenting until we create something that really works well for you. And if the braces don’t work as you’d like, don’t use them. I won’t be offended.”

What could I say? So Marcelo and I set about making the braces together. With our four hands we made the molds of my legs. Then Marcelo made the polypropylene braces, and we worked on them together until they fit just right and provided support exactly where I need it.

As a result, today I walk better than I did 30 years ago—thanks to a disabled villager who was willing to work with me as a partner and an equal.

A Similar Story With My Brother’s New Leg

Several years later Marcelo also helped my brother get back on his feet. My brother Rick, who has the same disability I do, lived in a small shack in New Hampshire, in north-eastern USA. He was very poor. Coming out of a church soup kitchen one night he was run over by a car and lost his leg. As he was over 65, his treatment was covered by Medicare. An expensive prosthesis was made for him. It needed a series of adjustments. But because of all the bureaucratic red tape, adjustments that should have been made the next day were delayed for months. A year and a half went by and my brother still didn’t have a usable prosthesis!

In desperation, I took my brother to PROJIMO. There Marcelo made him an artificial leg. Day by day he worked with my brother making the necessary adjustments. Then Marcelo taught him to walk, starting on parallel bars, then on crutches. Finally, with Marcelo’s help, my brother learned how to climb up and down steps.

So it was that Marcelo—with my brother as with me—succeeded where the highly trained professional and the sophisticated medical system in the US had failed. This was not because he had more technical expertise, but because he had more heart. It was because he and my brother worked as friends and equals in the problem-solving process.

Marcelo’s Family Moves to the State Capital

PROJIMO has always operated on a shoestring. For Marcelo, on his modest wages, it wasn’t easy to feed seven mouths. His wife Chayo did her best to supplement the family income by baking bread and doing odd jobs, but in the small village of Coyotitan there was a limit to what she could earn. So in 2005 Chayo moved with her younger children to the city of Culiacan, where she could put more food on the table by working in a restaurant. For nearly a year Marcelo stayed in the village of Coyotitan and continued the work he loved at PROJIMO. But he desperately missed his children. So at long last he left PROJIMO to rejoin his family in Culiacan. There he got a job making assistive devices with Más Válidos, a Community Based Rehabilitation program started in the late 1980s by two disabled PROJIMO “graduates.” But before leaving PROJIMO, Marcelo had carefully trained Alberto, a young amputee, to make prosthetics. The first limb Alberto made under Marcelo’s guidance was his own.

Marcelo and his family managed fairly well in Culiacan. Although living expenses there were higher than in the village, with both parents working they were able to keep their children in school and make ends meet. They gradually fixed up a large old house they’d moved into. Marcelo set up a small prosthetic shop in a back room. They were poor but the family was close knit, and for the most part they were happy.

Then in April of 2008 Marcelo began to get headaches. From day to day they got worse until he was unable to keep his food down, and couldn’t sleep. Medical tests and x-rays showed he had a malignant brain tumor that had already metastasized to his lungs. He went downhill fast.

Scores of family and friends visited Marcelo in the hospital. But his underage children were not allowed to see him there—which made it much harder for both him and them. It was then that he and Chayo made a difficult decision. With the help of sedatives and painkillers, he was able to return to his home for a few days. In those last few days his five boys were with him constantly, and even climbed into his bed with him at night.

When Marcelo took a turn for the worse—and was barely able to speak or lift his head—he asked to be taken back to the hospital, mainly because he didn’t want to have his children see him as he deteriorated further. Just a few days later, with Chayo holding his hand, he stopped breathing.

A Reflection

What is it that turns a markedly disadvantaged child into an exceptionally capable and compassionate adult? In these dangerous and difficult times, it is a question that merits our attention.

We live in an age where too often the key decisions that shape our collective future are made by the few at the expense of the many. In terms of working together for the common good, humanity has lost its humanity. Socially, spiritually and ecologically, we’ve run amok. Our leaders have led us down a blind alley. The institutionalization of greed and aggression has upset the poetic balance of life and sunshine that sustains us. We are on the brink of a tipping point where our very future on this planet is in danger.

Yet for all the insatiable pursuit of self-improvement that disharmonizes today’s world, there are still pockets of compassion. There are still some exceptional persons who find their deepest satisfaction in quietly helping others. Marcelo was such a person. It is on such unassuming, compassionate nonconformists—the followers of a different drummer—that a way forward for our endangered species depends.

Efforts to Help Marcelo’s Family

Marcelo’s passing has been a big loss to many people, but to none so much as to his immediate family. The youngest child, Rodrigo, is only five years old. And four of the five children are still in school. Chayo now works full time in a restaurant, and the older boys also work—when they can find jobs. Last year the second oldest son, Jossué—who still has neck and back pain from a car accident—while attending law school somehow managed to hold down a 10-hour-a-day job. The family is still struggling to pay off debts related to Marcelo’s illness and burial.

The good news is that a number of friends of PROJIMO and Marcelo have been pitching in to help his family make ends meet, and above all to make sure the children can continue with their schooling. HealthWrights has set up a special fund from which we send the family a modest amount each month to help with basic needs.

Request for Assistance

If a few more of you who remember Marcelo could make a donation—preferably a small monthly amount on an ongoing basis—this could make a big difference to the family. If you are able to help, contact David Werner or Teresa Hernandez at healthwrights@igc.org.

To help the family become economically self sufficient, HealthWrights and friends have been helping to set up a small welding shop, where the older boys can provide welding services in the neighborhood. They learned the basic skills from their father, who also had a lot of the necessary equipment. But some money to cover set up costs is still needed. If you are interested in contributing, contact us at healthwrights@igc.org.

Request for photos of Marcelo We would like to ask former visitors to PROJIMO who have photos of Marcelo to send copies to us, either as prints or digitally (on CDs or high resolution e-mail attachments). We hope to put together an album for the family—and for PROJIMO—in memory of Marcelo. Also, if anyone has a particularly fond memory of Marcelo, and could jot it down in a few lines, this could make a lovely addition to the album.

Thanks so much to all of you who knew and loved Marcelo. He was a rare soul whose memory—and family—are worth preserving.

Workshops For and With Disabled Children in Colombia: A Slideshow Presentation by David Werner

In our previous Newsletter, we presented the workshops on disability I conducted in Colombia. These are vividly captured in an exciting narrated full-length, full-motion slide show, with many examples and photos of each child.

This new resource is a great teaching/learning aid, with many original ideas. As with all our work, we put the disabled persons and their families at the center of the creative process.

Workshop Schedule

-

Day 1 – Presentations on Community Based Rehabilitation and Independent Living.

-

Day 2 – (Morning) Workshop participants visit the homes of the children.

-

Day 2 – (Afternoon) Small groups work on their plans for the assistive devices.

-

Day 3 – (First hour) Children and family members present their findings and designs.

-

Day 3 – (All day long) The small groups construct and test the assistive device.

-

Day 3 – (Final hour) Presentation of the finished device, evaluations, and conclusions.

The CD is currently available in English. The Spanish edition is in production, and is slated to be released by the end of 2008 (no promises for the holidays, sorry.) We are taking advance orders (see the insert with this newsletter), and will ship them as soon as they are complete.

The price for the English or Spanish edition is $15 (poor country price: $3.00) plus shipping.

The photos on this page are a preview of the show.

|

|

|

|

|

|

End Matter

To help reduce costs and resource use, please subscribe to the Electronic Version of our Newsletter. We will notify you by email when you can download a complete copy of the newsletter. Write to newsletter@healthwrights.org.

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Myra Polinger |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing and Photos |

| Jim Hunter — Editing |

| Jason Weston — Design and Layout |

| Trude Bock — Proofing |

We want to build a world where it is less difficult to love.

—Paulo Freire