Namesakes Resulting from Where There is No Doctor

Since I first wrote and illustrated Where There is No Doctor in Spanish, in mountain villages of Western Mexico in the early 1970s, the book has been translated into at least 100 languages (that we know of), with more than three million copies in print. According to the the World Health Organization, it has become “the most widely used community health care handbook in the world.” We have received letters of appreciation from health workers and families in scores of different countries, often with stories of how they used the book to treat the sick, save lives, and take collective action to prevent disease.

On a few occasions, families have been so pleased with the book, that

they have named a new-born child after me. Here I give a couple of examples.

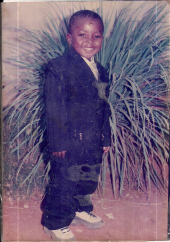

—from Ghana, Africa

Fifteen years ago a letter to me arrived from Ghana, Africa, from a young couple working in community service, who had extensive use of the Africanized edition of Where There is No Doctor. With their letter they sent the photograph of a baby, whom they had named Yaw Werner. Over the years they’ve sent me photos of Yaw Werner as he is growing up. And just a few weeks ago they sent me a few weeks ago the sent a photo of him, now 15.

|

|

|

|

|

|

—from Guatemala, Central America

In November, 2015, I received the following hand-written letter from a

young community health worker from deep in the jungles of the Petén,

Guatemala:

Libertad, Guatemala

6 November 2015

Hello David Werner !! How’s are you? I send you warm greetings from the cradle of the Mayan Empire. It is a pleasure to write from these distant lands that have received in a very good way the knowledge embodied in your book Where There is No Doctor, and others.

I want to tell you that I am the son of Pedro Ixchop who trained as a health promoter in 1980, in Quieritmo in Quetzal, Potzún, Peten. He gained knowledge of the book from Sheila. This knowledge came from fertile land, and he was the first in the community to work in a basic health unit.

I am the fourth and last child of my family. I was born on April 28, 1988: my parents decided to name me Werner Obeníel, the name that appears on your book. My father died on May 24, 2004 of diabetes, and I am left with the desire to be like him.

In 2011 the opportunity arose for me to begin my training as a health promoter from Susana (Emerich) and other health promoters from Cauce, Peten. I want to tell you that I have your book Where There is No Doctor. I was so happy to have it, because I identify with the book as it bears my name. I finished my training in 2013.

I want to say that I keep my father’s stethoscope and some of his brochures. I support my community as a health promoter, and this year I started my training as a dental promoter. I am excited because I am now practicing and have performed fillings, extractions, tartar removal, and prophylaxis.

I leave you wishing you health and strength to continue the grand work in the service of others.

- Werner Obeníel Ixchop Lopez

|

|

|

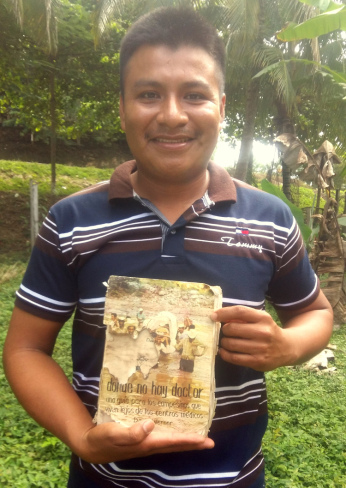

Weeks after I got this letter, an advisor to the village health program, Julia Kim, sent me a photo of Werner Obeníel holding the tattered but treasured copy of Donde No Hay Doctor, which had belonged to his father, back in 1980. With the photo Julia sent the following note:

Hi David!

[Werner Obeníel] did receive your letter today and he was full of excitement, to say the least. If it were me I would’ve opened your letter right away whether I had patients waiting or in the middle of a consult, but Werner waited ’til lunch time until he finished attending his morning patients. That’s the kind of promotor/person Werner is. He said “I want to open the letter so badly but I have patients.”

|

|

|

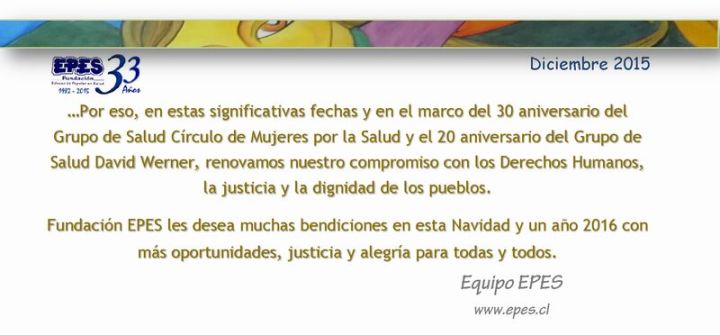

—from Chile, Central America

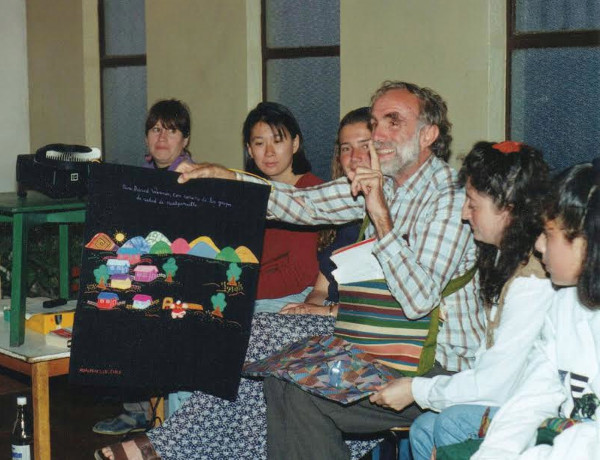

Sometimes a whole group has given itself my name, in appreciation of my work and writings. Just before Christmas, 2015, I received a notice from the founder-director of EPES (Popular Education in Health) in Chile, telling me about recent celebration of the 20th anniversary of the “Health Team David Werner.” The following photo of the announcement was attached.

—from Mexico, Central America

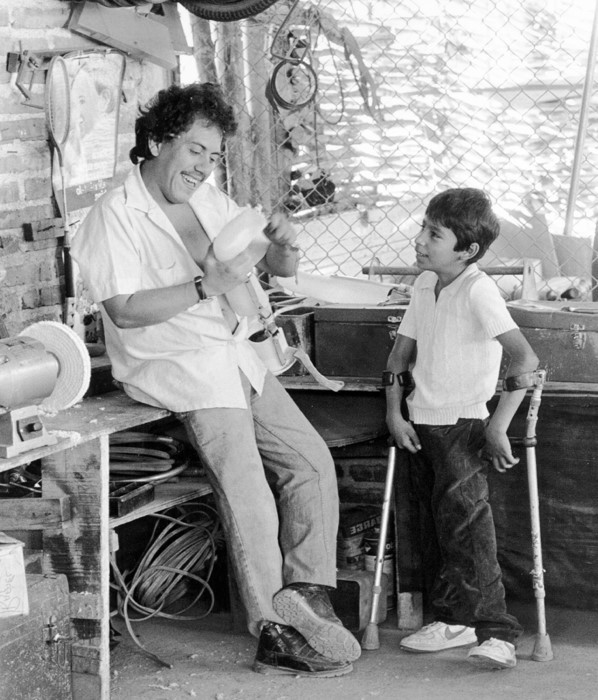

From Mexico, where I have been immersed in community-based health care and rehabilitation for more than 50 years, a number of people have named their children after me. One such person is Tomás Magallanes Ochoa, my friendship with whom extends over 34 years, since he was a young child. His mother first brought him to our community-based rehabilitation program, PROJIMO – Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico – when he was six years old. In his infancy Tomás’s legs had become paralyzed by polio and he was unable to walk. Our village orthotics technician (brace-maker), Armando, made plastic leg braces for Tomasito, with which he was able to walk, using crutches.

Because Armando, likewise, had paralysis from polio in childhood and was unable to walk until he came to PROJIMO, he was an inspiring role model for Tomás, who followed his every move in admiration as Armando worked on his braces.

On one of his visits to PROJIMO, as Tomás was watching Armando modifying a new pair of braces for him, the little boy declared, “When I grow up, I want to be a rehab worker, too. I want to help disabled kids get around better.”

And so it came to pass.

Tomás family lived in hut in a poor barrio in the coastal city of Mazatlán. Over the years his mother kept bringing her son back to PROJIMO. It was a long trip, for in those days was situated the village of Ajoya, at the foot of the Sierra Madre, about 100 kilometers to the north-east of Mazatlán. However there was nowhere in the city where they could the same quality of service at a price they could afford. Sometimes they would stay for days, helping in the project in exchange for room and board.

At PROJIMO Duranguito, Tomás became one of the most innovative workers.

In turn, on my trips to Mazatlán, Tomás’s family always welcomed me to their modest home and invited me to stay overnight. I became quite close to the whole family. Tomás’s father was an abañil (brick-layer) and often unemployed. At times they didn´t have enough to eat, or to pay for electricity or water. But they always invited me to share what little they had. I, in turn, would help them out in modest ways – especially in times of crisis, which were frequent.

Tomás had little love of school. He got along better with the street-kids than his schoolmates. In his vacations, as an adolescent, he would sometimes visit PROJIMO – where he felt well accepted by the disabled team. There he would help out, first in toy-making workshop, and eventually in the brace-making and wheelchair shops, where he quickly picked up skills. Though short of stature, thanks to his crutch-use he had remarkably strong hands … and an imaginative approach to problem-solving.

Tomás dropped out of school when he finished the secondaria (9th grade), at age 16, in the hopes of finding work. Yet that wasn’t easy in an environment where unemployment, even among the able-bodied, is extremely high. For a while he got a job packing fish at the wharf. But he was too mischievous and it didn’t last.

When he was 17, Tomás fell in love with and married a 15-year-old girl, named Mari. Soon they had a baby, whom they named David, after me.

Tomás was a devoted father, and shared – more than many fathers – with the caretaking of the child. But eventually the couple broke up. Because lack of the wherewithal to meet their basic needs, Mari and the child moved to Baja California with her parents. Tomás was heartbroken.

Around this time Tomás got a job at the PROJIMO Duranguito children’s wheelchair program, a sister program to PROJIMO rehab program, formerly based in Ajoya (now in the village of Coyotitán) where Tomás had first gone for braces as a child.

At PROJIMO Duranguito became one of the most innovative workers in figuring out what adaptations would work best for a particular disabled child. As he expresses this in his own words in a website he helped set up:

I have worked since I was little in rehabilitation programs in the fabrication of wheelchairs. I have been a part of PROJIMO Ajoya and of PROJIMO Duranguito in Sinaloa, Mexico. It enchants me to make special wheelchairs for children and adapt them to the necessities of each person, so that the children are in the best possible position and the family can transport them easily.

Tomás takes a personal interest in each child he works with, and often close friendships develop. One little boy who became devoted to Tomás was Miguél Ángel León. Miguél Ángel was born with spina bifida (a congenital defect of the spinal cord causing partial paralysis in his lower body.) Miguél Ángel needed a wheelchair, but if his club feet could be straightened, he had potential of walking with crutches. So Miguél Ángel and his family strayed for three months at PROJIMO Duranguito, while the team gradually straightened is feet with serial casting. Because Tomás sometimes used a wheelchair, and sometimes walked with braces and crutches, he was in a good position to teach the boy to walk with crutches and his new braces.

Just as Armando had been an inspiring role model for Tomás when he was a boy, so Tomás was now for Miguél Ángel. The two became great pals. And Miguél Ángel, in turn, talks about becoming a rehab worker when he grows up.

For the full story of Miguél Ángel’s inclusive rehabilitation at PROJIMO Duranguito see Newsletter #71: “A Seven-Year-Old Discovers New Life”.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |