Renaissance of the village of Ajoya and its revered ‘putting the last first’ clinic

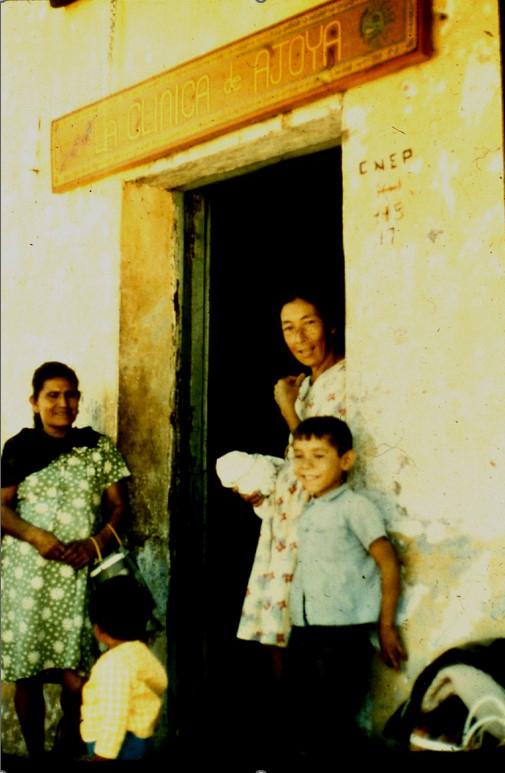

Readers who have been following our newsletters over several years will be aware that the villager-run health program in Mexico’s Sierra Madre, which for decades was based in the picturesque riverside village of Ajoya, has—to put it mildly—had its ups and downs. Because of a wave of crime and violence that intensified in the mountains of Sinaloa after the turn of the century, most of the region’s inhabitants fled to the coastal cities. For over a decade Ajoya became virtually a ghost town, everything falling into ruins. But incredibly, this distressing situation has now reversed. The deserted village is being repopulated, the collapsing houses rebuilt, and the famed Clínica de Ajoya handsomely restored. The dying village has now been resurrected as a “model community” where the needs and rights of everyone are caringly attended.

But how did all this happen? The remarkable story of this backwoods metamorphosis, told below, will be the main theme of this newsletter. To relate it, I annex below the “epilogue” I recently was asked to write for the forthcoming publication of the Spanish edition of my most recent book, Reports from the Sierra Madre: stories behind the health handbook, Donde No Hay Doctor. But first, let me tell you how these fortunate new arrangements for publishing the Reports in Spanish came about.

Publication of a Spanish edition of Reports from the Sierra Madre

Putting out a Spanish edition of Reports from the Sierra Madre has proved to be a much bigger task than we anticipated. The original English edition, published by HealthWrights, has now been available through Amazon for over two years. It is, in essence, a copiously-illustrated collection of eye-opening stories, which I wrote back in 1966 during my first year as a novice health worker in a remote region of the Sierra Madre, quite literally where there was no doctor. During that year, often late at night by oil lamp, I scribbled the series of four lengthy reports. With the help of volunteers back in California, the reports were typed, mimeographed, and sent out to the many friends and acquaintances who had subscribed in advance. In this way I raised a bit of money to help cover the (very modest) expenses of the budding village health program. (I also raised funds by selling some of my paintings.) From recipients of these reports we got enthusiastic feedback. Jotted down on a day by day (or better said, night by night) basis, the writings recorded the joy and challenges of the people and the adventures of the village health program as they unfolded. Readers said these impressions had a freshness and veracity that quite moved them.

Decades later, on rereading these early Reports, I and some of my pals had the bright idea of publishing them together as a book. However, these original reports had a shortcoming. Having been produced as mimeographed copies, they were almost devoid of illustrations. This seemed a shame, given that the Sierra Madre and its people are so beautiful. Hence the opus in English is replete with illustrations, many delightful, some disturbing. There are over 240 photographs, drawings and paintings, most of them my own … most in full color.

The problem with color

Reports from the Sierra Madre, the original English edition, is currently available through Amazon for $34. In the United States, this price is sufficiently high that its sales have been fairly limited. But now that we want to get the Spanish edition widely available in Mexico and the rest of Latin America, for many potential readers such a high price would be prohibitive. What pushes the price up is printing in full color. In looking for a publishing house in Mexico, we found that Editorial Terracota—which now publishes the updated version of Where There is no Doctor—is eager to publish the book. But in order to keep the price down low enough to encourage good sales, ET wanted to eliminate use of color and print it in black and white. This seemed a great pity, since the plenitude of colorful illustrations adds life and beauty to the opus. For lack of agreement on this issue, no contract was signed with Editorial Terracota.

Then came an exciting breakthrough! Through the connections of a leader in the renovation of the Ajoya clinic, I was invited to give a keynote presentation on my health-related books at the prestigious, annual Feria del Libro (book fair) organized by the press of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa (UAS). My presentation, with PowerPoint images, was attended by the president of the university and also the director of the university press, who introduced themselves to me after my talk. I showed them the English edition of Reports from the Sierra Madre and they were impressed.

To make a long story short, the university press committed to publish the Spanish translation of Reports from the Sierra Madre—in full color! The director explained that they could print it in color yet keep the price relatively low because the UAS Press, as a non-profit publishing house, doesn’t have to make much of a profit. (As a rule, commercial publishers set the retail prices of their books at six times the cost of production!)

Progressing full speed ahead, the UAS Press produced the first printing for the Feria del Libro in April 2023. Fortunately, less preparatory work was required than usual, insofar as the book had already been translated by an international team of volunteers, and then fine-tuned to the dialect of the Sierra Madre by a native speaker, my good friend Efrain Zamora.

This newsletter concludes with a translated, somewhat shortened version of the epilogue to the Spanish edition of Reports from the Sierra Madre, telling the fascinating story up till today of the incredible renaissance of Ajoya and its revitalized clinic.

Epilogue to the first edition in Spanish of Reports from the Sierra Madre

I am attaching the following epilogue—or closing reflection—to this first edition in Spanish of Reports from the Sierra Madre, to share with readers something about the long and extraordinary evolution of the Piaxtla village health program and where the renovated Ajoya Clinic stands today.

When I first became involved in health promotion in the Sierra Madre, toward the end of 1965, my intention was to stay one year only and then return to teaching biology in California. But I’d become so fond of the villagers and their struggle for their health and rights that I decided to stay a little longer. Now, 57 years later, I’m still entangled with the same venture, and its offspring.

In the half century that I’ve been involved in health promotion in the Sierra Madre, we’ve seen both ups and downs. Impressive successes have been achieved, with marked improvements in health indicators in the mountainous region covered by Proyecto Piaxtla. In the first ten years, both infant and maternal mortality dropped to a third of what they were previously. And the books that grew out of the backwoods community programs are still having a far-reaching international impact. Where There Is No Doctor, a village healthcare handbook—which I composed for the use of the marginally literate families in the Sierra Madre—has been translated into more than 100 tongues, with over 4 million copies in print. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized Where There Is No Doctor as “the most widely used book in primary health care worldwide.” The companion volume to Where There Is No Doctor, titled Helping Health Workers Learn, received WHO’s first international award for health education. And the manual Disabled Village Children, which grew out of PROJIMO (Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico) became the most used manual in the global south in the field of Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR).

Perhaps the most far-reaching impact of the villager-run programs in the Sierra was its contribution to “putting health in the hands of the people.” In those times, the dominant strategy to improve low standards of health was to impose the Western medical model on marginalized populations of the Third World. Health services were designed and performed by expensive doctors and their underlings. The process was very much “top down,” with the people needing care on the bottom. By contrast, the community-based initiatives in the Sierra Madre were directed and operated by local villagers, selected by their neighbors for being empathetic, dedicated to serving the most needy. Thus, the leadership and services came from the people themselves. This unleashed a process of empowerment that inspired participation and solidarity in the pursuit of health for all.

This liberating, bottom-up model, which similarly evolved in other parts of the so-called “developing” world, over time led to revolutionary change in the methodology of health promotion. In time, the World Health Organization began to promote community-based programs locally directed by the inhabitants themselves. And although it had at first discredited my books for providing unschooled people with too much information, it soon was promoting and sponsoring the translation and use of the books in community health programs throughout the majority world.

For all the local successes of the health and rehabilitation programs developed in Ajoya and the surrounding rancherías, in recent decades the pueblos of the Sierra Madre have gone through some distressingly difficult times. A major economic and social crisis was triggered, in part by the “North American Free Trade Agreement” (NAFTA), which started in 1990. Among other things, NAFTA legalized tariff-free exportation and importation between the United States and Canada and Mexico. So Big Agribusiness in the North began exporting to Mexico vast quantities of farm products, mainly of corn and cattle. Heavily subsidized by the US government, these agricultural corporations could sell their produce at prices lower than what it cost small farmers in Mexico to produce them. Thus NAFTA produced a socioeconomic disaster for campesinos, who couldn’t compete with the low prices of imported produce. Throughout Mexico this caused a massive exodus from the rural area to the mushrooming slums of the cities. The result was enormous poverty and despair among a large percentage of the population. This, in turn, precipitated a tsunami of crime, violence, and drug trafficking, especially among the young, who saw no other future.

In these difficult times, many pueblos and ranchos in the Sierra Madre emptied and became ghost towns, including the roads-end village of Ajoya and the surrounding rancherías. For a year or so, the health and rehabilitation team members continued to serve the dwindling population. But after further escalation of violence, many of the PROJIMO team fled to the coast, where things at the time were calmer. The team formed a new rehab center in the town of Coyotitán, along the coastal highway.

The few PROJIMO workers who had remained in Ajoya—mainly the builders of customized wheelchairs, hung on for another year or so. And I stayed with them. But finally, these valiant remaining crafts-persons also fled their beloved town. They moved to the small village of Duranguito de Dimas, miles from the mountains and, for the moment at least, more peaceful.

In the largely abandoned village of Ajoya, violence came to a head on Mother’s Day, May 10, 2002, during a street festival to pay homage to mothers, organized by the remaining teachers and schoolchildren. It was the first after-dusk festival that the remaining villagers had dared hold since the exodus began. And tragically, it did not end well. While the villagers were dancing in the street, a confrontation broke out between a group of soldiers, who were supposedly protecting the town, and a gang of drug dealers and hoodlums, who were stealing with impunity and extorting money from the more affluent families. These 20 or so malandros (bad doers), who had been boisterously dancing with villagers, suddenly whipped out their guns and began shooting at the soldiers, who were standing guard on the sidelines. The startled soldiers at once returned their fire—shooting into the crowd of dancing people.

This Mother’s Day Massacre, as it’s been called, resulted in the injury or death of many innocent people: those dancing in street and onlookers, some of them children.

The massacre caused the frantic exodus of almost all who’d dared remain in the village up until then. Ajoya, at its maximum population, had more than 1,400 inhabitants. At the time of the massacre, only about 200 residents remained After the massacre just around 60 remained (quotes from Yolanda Tenorio, journalist from El Debate). The few Ajoyanos who stayed were mostly folk too poor or otherwise unable to move. The beautiful village of Ajoya was left abandoned and crumbling for the next 13 years.

Then, wonder of wonders, in 2017, Ajoya’s miraculous renaissance began! As it turned out, a group of native Ajoyanos—some of them now accomplished professionals and/or retirees, many of whom had been teenagers when their families fled their hometown—lamented that the beloved haven of their childhood was falling apart. Collectively, they decided to launch an initiative to rebuild their village. Some with more financial means contributed generously. They began to rebuild the collapsing houses, one by one, hiring many of the residents who remained. Their vision was not only to restore the destroyed pueblo but to transform it into a model peaceful community. Rules were agreed upon not to carry weapons in the street, nor to allow sale of alcoholic beverages stronger than beer. They disallowed the sale of mind-altering drugs and the cultivation of narcotic crops. The idea is to create a communal environment where everyone enjoys helping one another. They remodeled the village square and planted trees and lovely gardens.

To repair the roof and interior of the old church, the renovators drew on resources from the municipal government. And with support from the state government they flagstoned the main streets. To add to the overall charm of the public space, with the help of local artisans, to one side of the reconstructed church they designed a small but a beautiful plaza (square), which they called “Renacimiento Ajoyano” (Ajoya Renaissance) in reference to the restoration of the village, physically and socially, that was persuading so many of the departed families to return. This new plaza they adorned with a long enchanting mural designed by the community’s cultural and health promoter, Genaro Ocio, and painted by his friend, Jerónimo Aguirre, a well-known artist from the nearby village of La Labor. Returning families with sufficient means provided benches, flowerpots, and the central fountain, while others helped to pave walkways and create the luminaires. With the scores of reconstructed houses, painted in all colors of the rainbow, the ambiance was as picturesque as a fairy tale. The village is now much calmer and with a new sense of solidarity. Currently, even more of the families that had left are now returning.

Community library and study hall

With more and more families coming back to Ajoya with their children, the village renovators have taken pains to the restore the schools and other community buildings, as well as to improve access to distant-learning programs. Being so remote, the village had no telephone, cellphone or internet reception. So they set up satellite reception to enhance social, educational, and cultural communication. Also, they built an attractive multipurpose library, equipped with computers in separated stalls, so children (and adults) could engage in virtual learning with less risk of covid exposure. This helped to reverse the decline in “virtual school” attendance caused by the pandemic. Thanks to these measures, children were more able to keep up with their studies. This new library was named the “Biblioteca Comunitaria, Misión de San Jerónimo de Ajoya.” In search of donated books and learning materials, the cultural promoter reached out to academic institutions, government archives, and historians, as well as to conservationist researchers dedicated to the preservation of native species in danger of extinction, such as the jaguar, declining numbers of which still prowl the forests surrounding Ajoya. A splendid mural portraying the village’s colorful history was painted on the streetside wall of the new library. Called “Chronología Ajoyana”, the content of this mural—depicting key figures from the village’s colorful past—was once again designed by the village’s cultural promoter, Genaro Ocio, and painted by the gifted local artist, Jerónimo Aguirre.

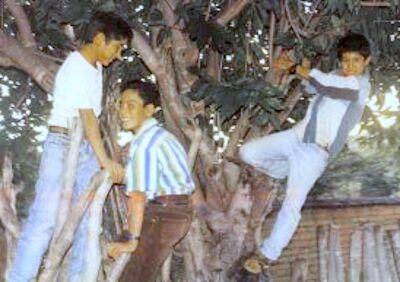

It turns out that several members of Ajoya’s restorative group, years before when they had lived there as children, had eagerly helped out in the community health and rehabilitation programs (projects Piaxtla and PROJIMO). Often, after school, they helped make wheelchairs, walkers, and other aids for children with disabilities, and assisted with their therapy and rehab. Likewise, many had participated in “learning by doing” Child-to-Child activities, where they’d discovered the fun of including and assisting, rather than excluding or making fun of, the child who is different.

When the renovation of Ajoya was well underway, I received a message from the group of renovators asking me to visit them in Ajoya. When I got there, they welcomed me warmly and asked if I would authorize the reconstruction of the old Ajoya clinic, which now lay in rubble. I explained that the clinic was never mine; it had always belonged to the community itself. But I told them I’d be very happy to see the old health post rebuilt and above all, functioning again to serve those most in need, as it did in the past. For me, it was painful to see the long-beloved health center all in ruins, with roof caved in and walls collapsing. To rebuild it would be a gigantic task. But the people insisted they were up to it.

It took more than two years to rebuild the clinic; it was slow but unflagging work. When it was almost completed, the community, animated by the cultural promoter, organized an homenaje (tribute) in my honor. I anticipated a small event, but more than 600 people showed up! Apart from current residents, former Ajoyanos and friends came from nearby towns and cities, along with doctors, journalists, and a team of newscasters. The latter had evidently announced the upcoming event in the statewide Sierra al Mar (Mountains to Sea) program. It had also been announced in the news media and online. As a result, the turnout for the event was—at least to me—unimaginably huge! It was without a doubt my biggest surprise and show of appreciation from this community to date.

All sorts of people came from all over the place, from the humblest peasants to esteemed celebrities, from health officials to the former municipal president, don Octavio Bastidas, who launched some flowery words in my direction.

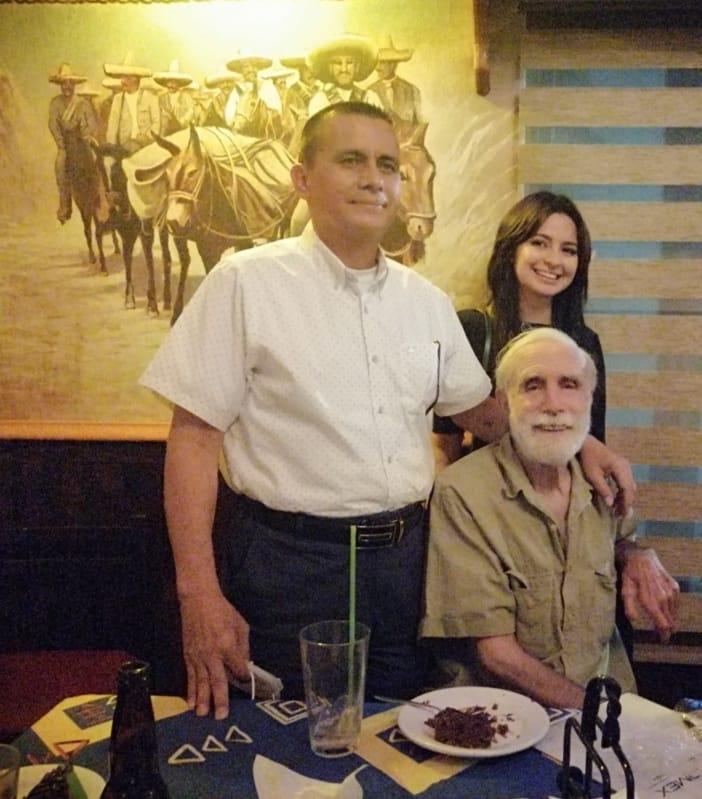

To my delight, a bus-full of disabled people arrived from Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa. I loved seeing so many friends again whom I hadn’t seen in years. One I was most happy to see was Dr. Carlos F. Soto Miller, now almost 80 years old. More than 50 years ago—when he was a young doctor just graduated from the Polytechnic Institute of Mexico City—to carry out his required year of medical service he collaborated with our rustic Ajoya Clinic in the Sierra Madre. Dr. Carlos had enthusiastically helped me when I was composing the first draft of Donde No Hay Doctor. At the tribute in Ajoya, Dr. Carlos spoke emotionally about his adventures and challenges in the clinic’s first year.

All in all, the tribute was an impressive event. I was a bit embarrassed by the many eulogies of appreciation that the doctors and authorities directed to me.

What thrilled me most on this festive day was the magnificent renovation of our humble clinic. Even from outside, its gleaming whitewashed walls are impressive. Over the entry, facing the street, stand out in large black letters, LA CLÍNICA DE AJOYA DR. DAVID WERNER. This big display of my name made me feel a little weird, for two reasons. First, I’m a biologist, not a licensed physician. Second, I never wanted to be seen as the owner or head of the clinic. Thus, the original health post was named after the community it served. Those in charge were the local promotores de salud (health promoters). I considered myself an adviser and instructor, nothing more. Therefore, to see my name in huge letters on the wall of the spiffy new clinic made me somewhat ashamed.

The new clinic was magnificent: modern and remarkably well equipped, complete with exam room, x-ray equipment, highly hygienic operating room, modern therapy facilities, a small pharmacy, up-to-date medical, psychological and dental offices, and much more, staffed by young professionals graduated from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, plus a couple of social workers from the Autonomous University of Guadalajara, who provide social work.

For all this, I still had my doubts. I found myself wondering: how is this impressive facility going to work, now that the former team of local promotores de salud, who had provided the services with such care, dedication, and understanding of local realities, were no longer there?

However the dedicated renovators of the new Ajoya clinic, spearheaded by the community’s idealistic cultural promoter, Genaro Ocio, and by orthopedic surgeon Dr. Renán Vega, were exploring other possibilities. They sought out charitable doctors from the coastal cities (mainly Mazatlán). These kind-hearted doctors were invited to make visits to Ajoya on a regular basis, to provide voluntary services to those in greatest need. And wondrously, little by little, a dedicated team was assembled, including some of the most skilled and humane physicians in their fields. Top-notch specialists were recruited in various disciplines, including surgeons, anesthesiologists, pediatricians, cardiologists, internists, orthopedists, dentists, psychologists, therapists, medical equipment suppliers, and more. Despite their busy lives and heavy workload in the city, they happily joined this idealistic cause—and more continue to do so.

To arouse the interest of such professionals and spark their collaboration, the coordinators of Ajoya’s renovation team invited me to give PowerPoint presentations to diverse practitioners, depicting the medical needs in the corners of the Sierra Madre, and recounting the unusual story of the programs that had been carried out there. I think what attracts such outstanding professionals the most is that the Clínica de Ajoya functions as a service, not a business. For health workers with a latent humanitarian bent, that’s a breath of fresh air.

Rebuilding my home

Among the scores of houses the renovators have rebuilt in Ajoya, one is my own—which they restored with incredible innovation and care.

It required a lot of challenging work, since the modest two-story structure, perched on the cliff overlooking the river, had deteriorated to wrack and ruin. The wooden components were pulverized by termites and the tile roof disheveled by iguanas. A large wild fig tree (zalate) had fallen on a corner of the building. And torrential summer rains, which year after year poured through the collapsed roof, had liquidated and befouled the interior. But for all this dread damage, the renovators rebuilt my house handsomely, in a very functional way. They added bedrooms a second bathroom, and a large kitchen, to accommodate doctors and others coming to serve in the clinic and community. I’m delighted that my renovated quarters will be put to such good use when I’m gone.

Dr. Renan Vega: médico with a big heart

Of the various health professionals who have collaborated in the renovated Ajoya Clinic, one of the most dedicated and capable has been the acclaimed orthopedic surgeon, Renán Vega Alarcón. Dr. Renán has a long and deeply valued history with our health and rehabilitation programs in Ajoya. He grew up in neighboring San Ignacio, capital of the municipality, where his father was an admired schoolteacher and humanist. Renán, too, had a big heart. Since childhood he’d heard stories about the community-based programs in Ajoya, and had been intrigued. He liked the idea of a health service run by the villagers themselves. As a teenager (40-plus years ago), he made his first visit to Ajoya, some 20 kilometers from San Ignacio at the end of a narrow dirt track. He arrived at the clinic and offered to help in any way he could. Thereafter, he occasionally helped out on weekends.

On finishing prep school, Renán studied medicine and then specialized in orthopedic surgery, at which he soon gained a highly esteemed reputation.

But Renán never forgot his formative experience in Ajoya. During the next three decades he continued to collaborate with the village health promoters, performing many free surgeries for low-income people they referred to him at his practice in the coastal city of Mazatlán. When the new Ajoya Clinic became equipped with a good operating room, Dr. Renán—who then practiced in several private clinics in Mazatlán and had an office in Clínica La Marina—on weekends began to consult and perform outpatient surgeries in Ajoya. Equally important, he made a great effort to win the collaboration of other doctors, in various specialties.

Among Renán’s initial recruits was his own daughter, Dr. Olga Torróntegui, a dental surgeon. Olga continues to work daily in the well-equipped dental room, and provides auxiliary support in the operating room when needed.

Little by little, the newly renovated Clínica de Ajoya began to gain a reputation for providing outstanding services. This has in large part been due to the tireless efforts of Renán: as a surgeon, as an organizer, and as inspirer of the best in others.

When Dr. Renán and the other doctors performed surgeries in Ajoya, they brought with them the necessary nurses, anesthetist, and other support personnel, who likewise willingly collaborated. Today the Ajoya Clinic not only responds to the medical needs of the surrounding ranchería but of the entire municipality of San Ignacio, and beyond. It especially reaches out to the people most in need: those who struggle to get care at the city’s health clinics—or whose families go hungry to pay for costly medical services.

Little by little, the new Ajoya Clinic has been gaining respect and a certain fame in the region. On several occasions, people who’d had poor surgical results in the city centers then went to Ajoya, where the volunteer doctors frequently performed interventions again, often with greater success. For example, a man had badly broken his leg in a motorcycle accident. In a hospital in Mazatlán a doctor had struggled to accommodate the bones correctly, but the leg remained very crooked and short. Later at the Ajoya Clinic, Dr. Renán managed to reposition the bones in correct alignment.

Customarily, Dr. Renán worked with tireless energy and enthusiasm. But in the months of 2022, he started to lose some of his energy. He continued traveling from Mazatlán to Ajoya on weekends, conducting consultations and performing surgeries. But his face was already showing lines of stress, and we noticed that he was losing weight. He finally told us he’d been diagnosed with lung cancer. The malignancy was aggressive and his health deteriorated rapidly. Nevertheless, he continued to participate in Ajoya as best he could. One of the last surgeries he did was on a child with a badly broken leg. Due to his damaged lungs, the good doctor was unable to inhale enough air, so he performed the surgery while breathing oxygen through a nasal tube. Two weeks later, he died.

The death of Dr. Renán Vega was a huge loss, not only for his family and friends, but also for the village clinic he loved and the community he served, especially the people most in need. He may no longer be with us physically. But for what this kind man did so gladly for others, for his selfless services, and for moving his peers to find joy through kindness, dear Renán lives on. He continues to inspire all of us who were so fortunate to know and work with him. With the example of Renán’s grand spirit and humanitarian service, may the Ajoya Clinic continue to evolve.

Readers of this epilogue will note that with the renaissance of the Ajoya Clinic, basic changes have occurred in the structure of services. In the old makeshift clinic, which started half a century ago, there were for the most part no licensed professionals. The center was managed by health promoters from the same community. They had little formal education and their learning was mainly through apprenticeship. But they shared the strength and dynamism of their own people. And they encouraged the population—women, children, sometimes even men—to protect and improve their health. In contrast, the impressive new Ajoya Clinic is very professional. It is equipped equally or better than many clinics in the cities. And its acclaimed services are provided by qualified professionals and highly trained yet humanitarian specialists.

Despite these striking differences between the rustic old health center and the modern new clinic, nonetheless the two have some vital characteristics in common. Both share the mystique of putting the last first, of serving those most in need with respect and affection, and without profiteering. They appreciate the value of all.

It is for all this that I, with deep appreciation, dedicate this first Spanish edition of Reports from the Sierra Madre—published by the Autonomous University of Sinaloa—to the memory of our dear amigo and colleague Dr. Renán Vega. His deeply caring example has been an inspiration for all the collaborators in the work of the new Clinica de Ajoya, that it may continue in the groundbreaking steps and transformative challenges of the old clinic.

For me, the most indelible thing about Renán’s contribution to the Ajoya Clinic’s revival was his tireless encouragement to give a hand to those most in need, always with respect and affection. This he did, not out of moral obligation or for heavenly reward, but out of deep compassion borne of his heart. His untiring readiness to give of himself for the wellbeing of others was so contagious that it inspired many of his colleagues to walk the same path. Though no longer with us in person, he continues to inspire us … and in this way his spirit lives on.

End Matter

| Board of Directors |

| Roberto Fajardo |

| Barry Goldensohn |

| Bruce Hobson |

| Jim Hunter |

| Donald Laub |

| Eve Malo |

| Leopoldo Ribota |

| David Werner |

| Jason Weston |

| Efraín Zamora |

| International Advisory Board |

| Allison Akana — United States |

| Dwight Clark — Volunteers in Asia |

| David Sanders — South Africa |

| Mira Shiva — India |

| Michael Tan — Philippines |

| María Zúniga — Nicaragua |

| This Issue Was Created By: |

| David Werner — Writing, Photographs, and Drawings |

| Jason Weston — Editing and Layout |